Transcribed from the 10 September 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Social movements like Black Lives Matter are vital components to trying to rebuild and revitalize democracy in the United States. Because it’s not just the left that we need to revitalize. Another lesson of our time is that democracy itself is on its last legs. That’s hard for a lot of Americans to hear.

Chuck Mertz: Black Lives Matter is radicalizing the US left, and it’s about time. And now the movement has come up with a series of demands and a Vision for Black Lives. Here to tell us how Black Lives Matter may have a new vision for the left, Martha Biondi wrote the In These Times cover story “The Radicalism of Black Lives Matter: Three years in, the youth-led movement has the power to transform the left.”

Martha is chair of the department of African-American studies and professor of African-American studies at Northwestern University, and she is author, most recently, of The Black Revolution on Campus.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Martha.

Martha Biondi: Thank you very much. Glad to be with you.

CM: Where I want to start is with the platform of a Vision for Black Lives. It states, “While this platform is focused on domestic policies, we know that patriarchy, exploitative capitalism, militarism, and white supremacy know no borders. We stand in solidarity with our international family against the ravages of global capitalism and anti-black racism, human-made climate change, war and exploitation. We also stand with the descendants of African people all over the world in an ongoing call and struggle for reparations for the historic and continuing harms of colonialism and slavery. We also recognize and honor the rights and struggles of our indigenous family for land and self-determination.”

What do we miss in our understanding of Black Lives Matter when we see this as a movement that is exclusively about black people?

MB: In some ways you just answered your own question by reading that list of concerns that have come organically from the Movement for Black Lives. I’ll remind listeners: just yesterday here in Chicago, local Black Lives Matter organizers helped organize a major demonstration in solidarity with the indigenous fight to stop the Dakota Access pipeline. There were several similar large demonstrations across the country. That is another prime example of how the movement has embraced a whole range of progressive issues that are at the core of revitalizing an American left.

But at the same time, their focus on race and policing has been extraordinary and is itself a major contribution to helping us understand the social crisis that we’re living in. One thing that’s amazing about social movements is that they create both new leaders and also new knowledge, and they deepen our understanding of the complexity of the social crisis that we face. When we think about the role of race historically in the United States and about what have been sites of social control, we might think of the slave ships, and then the plantations, and then maybe the racial ghetto. But this movement is forcing a broader group of Americans to understand the role of the carceral state, the carceral apparatus, and the police who are on the front lines of it.

That’s what I mean about creating new knowledge: helping us to see better what prisons so effectively hide from most of us.

CM: When it comes to democratic reforms, the Vision for Black Lives demands direct democratic community control of local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, participatory budgeting, and the end of school privatization. Vision for Black Lives also demands economic justice, including restoration of Glass-Steagall and an end to the TPP, a return to greater worker protections, job programs, black alternative institutions, and progressive restructuring of the tax code.

Is Black Lives Matter part of a global anti-neoliberal movement? Where should we place them within that movement that includes Occupy, Nuit Debout, Barcelona en Comú, the Indignados?

Or is this far less radical? Is it rather a progressive approach to economics? After all, it is in many ways now being embraced by the Democratic Party.

MB: People can debate nomenclature and what the differences are along the spectrum from radical to left to progressive. The proof is in the very courageous and principled stands that many organizations that are part of the Movement for Black Lives have embraced and undertaken, such as support for the BDS movement (and they’ve taken a lot of heat for that). They’ve been very principled, very out front; they have waged very searing critiques of our tax structure, of our economy, our prison system.

People running for office are trying to win votes. They’re trying to win elections, so of course they have to be cognizant of the discursive field that surrounds them and the kinds of issues that youth are raising. This is not new; we see this in every election cycle: politicians are attentive to the various issues coming up. How they’re going to govern—whether they will follow through on promises—is another question, and we have a long history of betrayal on that score. The fact that people running for office take up some of these issues during campaign season is significant, and we should push that and recognize that, but it doesn’t fool us into thinking that that itself represents a victory.

Social movements are vital components to trying to rebuild and revitalize democracy in the United States. Because it’s not just the left that we need to revitalize. Another lesson of our time is that democracy itself is on its last legs, and that’s hard for a lot of Americans to hear. American exceptionalism has created a certain sense of blindness. This discourse that the US is a unique and singular democratic and great nation that embraces liberty and equality is really becoming empty slogans and words in the lives of many Americans. Social movements have played a vital role in opening the eyes of more and more people.

It’s not just the Movement for Black Lives; it also includes Occupy, the Fight for Fifteen, the immigrant rights movement. All of these are part of the moment, as you said, of critiquing neoliberalism, of coming to understand that privatization, the valorization of markets, and the attack on unions are undermining democracy in America.

CM: So do you believe social movements can save democracy in America, and that without social movements it’ll be lost?

MB: I’m not going to pretend to have all the answers. But I’m an observer and student and participant in many of these movements, and I appreciate how they force us to have new conversations, to ask new questions, to see the world differently.

For example: reparations. The Movement for Black Lives is calling for reparations in a variety of ways. I’ve always been interested in the reparations movement because it forces us to see the central role that slavery played not only in the creation of wealth and the creation of the economy, but also in how it shaped the creation of our government. It’s a big reason why federalism came to emerge as a governmental structure. Why do we have the electoral college? Why do we have the filibuster? Why do we need a supermajority? These social movements force us to ask these questions, to rethink government in the US.

Can it have a positive impact in revitalizing democracy? The movements are pushing back against Citizens United, for example, and making people see the extraordinarily outsized role of money in shaping not only our electoral system but also our system of governance, and seeing how that directly undermines democracy. Do these social movements have the means to put over their vision of the future? Not right now. They’re not strong enough. But they are producing extraordinary insights and information that helps guide the way forward.

That’s what is so wonderful about this new social movement: it is waging creative protests, organizing, and educating people in a dire and challenging situation, in the midst of an extraordinary social crisis. They’re really to be commended for that, and to be studied and copied. We need to learn from their strategies and techniques, and spread it even further.

CM: In your In These Times article, you link to another In These Times story by James Thindwa, headlined “The black political establishment should never have given Hillary Clinton a blank check: the Sanders campaign was an opportunity to put pressure on Clinton, but instead the neoliberal black elite backed her unconditionally.”

This is something we’ve discussed at length with Glen Ford of Black Agenda Report, about how the neoliberal black elite is not doing a very good job of representing African-Americans. Is Black Lives Matter somehow similar to the Tea Party movement on the right, when it comes to a disconnect between the rank-and-file and the elites?

MB: I’m just going to approach that from the perspective of Black Lives Matter without necessarily drawing a comparison to the right. There’s been a real crisis in leadership for the working class in general, for black communities, for poor communities in the United States. The Democratic Party and elected officials in Washington have not been responsive to their interests. It’s the way congress is organized, the way federalism is structured. Our government does not do an effective job at producing public policy that is responsive to the needs of the low-income, the single mothers, the poor workers. It’s only in extraordinary moments of social crisis—whether it’s the Great Depression or the Black Freedom struggle—when we’ve actually seen congress pass laws that have been responsive to human needs. The rest of the time they don’t. And it’s not an accident. It’s part of how it’s structured.

That’s another conversation, but this goes beyond the way neoliberalism has captured the Democratic Party (though that’s certainly a big part of the problem that we face). Again, these social movements are revitalizing resistance, revitalizing the opposition perspective. The Movement for Black Lives is in many ways revitalizing black politics, if we think of black politics as a mode of resistance, as a source of articulating anti-racist struggles and anti-racist thought.

This young generation has come and pointed out that we have a black man in the white house, yet racial disparities are rife in American life; racialized policing is a threat and menace to black people across the country. They’re refusing to drink the Kool-Aid of a “post-racial” society, of a “colorblind” society, and they have forced the issue of race back into the national conversation in an extraordinary way—in a concerted, organized, persistent way, for the first time since the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power era.

And it’s really, really important, because the idea that we were in this colorblind, post-racial America had gotten traction during the Obama era. These young people are saying no, and they’re forcing us to think about race in a new way.

CM: Did Black Lives Matter happen because we had an African-American president?

MB: Some people have argued that. Keeanga Taylor, in her magnificent book From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, suggests that. There’s a lot to that idea, that this generation was raised on the notion that the Civil Rights Movement was a success, and the final glass ceiling of the white house had been shattered, and we are in this post-racial nirvana—but they’ve learned first hand from their whole life experience that that’s a myth, it’s not a reality.

We see this again and again in history, the importance of students and youth breaking from older frameworks and paradigms, and waging direct action struggles, taking to the streets to force a different conversation. So yes, they’re very much products of their time and place, which includes having Barack Obama in the white house.

Of course the bigger context is the context of neoliberalism and mass incarceration. All of that preceded the election of Barack Obama, and that is the bigger social context that gave rise to this movement. It is a movement that was sparked by trauma: by violence and police shooting. That’s always important to remember.

CM: The Vision for Black Lives demands public financing of elections, full access and guaranteed protections of the right to vote for all people, net neutrality, and an end to the criminalization of black political activity as well as the end of money controlling politics.

How much is black political activity in the US today being suppressed by the US? How much is Black Lives Matter about the political system not giving access to black citizens?

MB: That’s a great question. When we think of political participation, for a lot of people what comes to mind is the right to vote. One impact of the carceral state and the racial dimensions of mass incarceration is that it deprives very large numbers of black people of the right to vote. This is what Michelle Alexander meant by “the new Jim Crow.” It is legal now in many states to deprive ex-felons, people who have been incarcerated, of the right to vote for the rest of their lives. They did their time, they come out of prison, but they can’t vote. That has affected people’s access to the ballot.

We know from history that whether it was the McCarthy era or the COINTELPRO era of the 1960s and 70s—and now in the post-9/11 era with the Patriot Act and the extraordinary spread of all kinds of government surveillance and technologies of control—that the government’s fear and anxiety about domestic dissent and about radical and leftwing organizing has never diminished, has never gone away. That deeply affects organizing in black communities.

This apparatus of repression, along with the effects of mass incarceration—and what neoliberalism, de-industrialization, and global economic restructuring have contributed: permanent unemployment and weakened unions—has really affected communities’ capacities to organize and resist. That’s what is so wonderful about this new social movement: it is waging creative protests, organizing, and educating people in a dire and challenging situation, in the midst of an extraordinary social crisis. They’re really to be commended for that, and to be studied and copied. We need to learn from their strategies and techniques, and spread it even further.

CM: So has Black Lives Matter, then, revealed the shortcomings of representative democracy in responding to the needs of minorities? And is that why Black Lives Matter discusses in their demands that they want direct democracy? Does Black Lives Matter show us that representative democracy is not all that democratic?

MB: A lot of things have shown us the problems in our electoral system. There have been scores of studies showing that Republicans have in very devious ways used technology to draw district lines for congressional seats in such a fashion that it has made it very difficult to unseat incumbents who can win elections with a very small number of votes. There we have a political party that is invested in reducing the electorate and reducing the power of voting through passing voter suppression laws and the way they draw district lines.

On top of that, there is the role that the filibuster has come to play in congressional daily life so we need supermajorities to pass legislation. Needing a supermajority in a system where the lines have been drawn in a rigged way, it’s going to be very difficult to pass legislation that will be responsive to human needs and responsive to the needs of the unemployed, to people who have poor and crumbling schools, who have poor and crumbling housing. Even if you do elect someone from your district who is very sincere and progressive and really wants to get things done, they’re entering a system in Washington that is designed to thwart that.

The Movement for Black Lives is helping us see that better.

They’re saying let’s defund police; let’s fund black futures instead of funding police departments. Let’s re-invest in these communities so that policing isn’t our response to a social crisis. Jobs and education will be a response to our social crisis.

CM: You write, “This defiant black-led youth movement is the first of its kind since the black freedom struggle of the 1960s. It’s important, however, to see it not only within the history of black struggle, but within the history and future of the left. Many may associate the US left and socialist traditions with white male leadership, a focus on class, and a disregard of race, gender, and sexuality, but this is inaccurate and incomplete. Black, Latino, and Asian-American activists of all genders have participated in old and new left traditions for over a century. Yet for many young activists of color, the word ‘socialist’ still has a white male ring to it, and the Sanders campaign’s initial fumbling with Black Lives Matter unfortunately revived this older association.”

What explains this disassociation of blacks with the word “socialist” and the importance of black struggle within the history of the US left? After all, isn’t it the left that’s supposed to be the political ideology that is most supportive of racial justice?

MB: This is a great question. The history of socialism in the United States is complex. It has a strong lineage of European immigrant workers, certainly in the early twentieth century, for whom race and racism, white supremacy, was not at the forefront of their thinking. But there is another long lineage of American socialism that’s always been multi-racial, that’s always been diverse, included African-American agricultural workers and urban workers after the Great Migration, and has always tried to push issues of race and racism into the socialist agenda.

So there is a long history of myopia around racial issues for some American socialists, but there is also a countervailing tradition of black and Latino socialists and leftists and communists trying to push these questions.

Another interesting feature of black life and black politics is that because of the ways in which African-Americans have always been pushed to the margins of the formal economy and have been disproportionately poor workers across American history, African-Americans across all segments of the population have been the most open to government intervention in the economy; the most open to socialized medicine, a single-payer health care system; the most open to redistributive measures in the economy; and the most open to progressive taxation.

They don’t always have a socialist party that is leading that call. But if one looks at public opinion polling and surveys in terms of which Americans are most open to what we might describe as a socialist message, it’s overwhelmingly African-American, and that’s been true across the twentieth century.

CM: So has Black Lives Matter re-energized the left? Or has the left—Occupy, the anti-globalization and antiwar movements since the Battle for Seattle and the Iraq War protests—re-energized African-American politics in the form of Black Lives Matter?

MB: There is cross-fertilization among all of these movements; we’re all in some ways occupying the same space. And yet we still live in a hyper-segregated society, so it’s no accident that we’re going to see segregation and racial separateness in our social movements. But at the same time there’s conscious efforts to promote cross-fertilization and dialogue across these movements.

So the answer is both/and. I think that the Movement for Black Lives is the American left; I think that Occupy is the American left. And I think the social movements that are predominantly white or predominantly non-black need to ask themselves all the time to think about race and racism, to think about how these dynamics affect the internal cultures and the agendas of their social movements.

This is the complication of trying to build a left in a country that’s hyper-segregated. It’s never going to be simple or easy. But we always have to say to ourselves: how do we create a real ethos and culture of inclusion and democracy within our movements? How do we attend to allied fights and struggles? How do we incorporate multiple issues in our own organizations even if they seem to be focused on a single issue like Fight for Fifteen or immigrant rights? All of these movements are trying to think about these questions. Some do it better than others, but I think if we’re going to be ethical and principled people on the left, we have to be sensitive to the multifarious nature of oppression as it operates in the United States as we envision and strive to create a better world.

CM: Martha, are police the reason that black politics have been radicalized? Did police radicalize black politics?

MB: This movement was launched by traumatic events, police shootings. Of course this has been extraordinarily important in mobilizing the grief and despair and anger and outrage that brought people into the streets.

Now the movement is developing. It’s trying to go beyond that and articulate a vision for the future; we see that in the platform that you began this interview telling your listeners about. Movements have histories and genealogies and developments. So it started as a response to police violence—but we should ask why this police violence is happening. The movement is forcing us to ask that question. Why the police? Why are they at the front lines of race and racism and racial control?

Part of it is because of the long history of stop-and-frisk style policing, of using the police to contain these communities that have been written off. There are no jobs. There are no high property taxes to pay for schools. There is just crumbling and poor housing. These are communities that have been written off from a formal economy, and politicians have given police instructions to come back with this quota of arrests, to engage in this racialized policy of stop-and-frisk.

When that goes on for decades, then the police are essentially being instructed that these people’s lives matter less. They are less than human. And that is going to result in what we’ve seen: in abuse, in killings, and it goes unpunished by the same politicians who gave them this role to play in our society.

These movements for black lives are forcing us to see the underlying social and political dynamics that have led up to this situation. What’s brilliant about them is they’re saying let’s defund police; let’s fund black futures instead of funding police departments. Let’s re-invest in these communities so that policing isn’t our response to a social crisis. Jobs and education will be a response to our social crisis.

They’re trying to unravel this police nation that we’ve created, this prison nation, and to ask how we can devise public policies that are about black lives mattering instead of about black death and suffering.

CM: One last question for you Martha, and it’s what we call the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

To what degree is white liberalism open to black radicalization?

MB: It’s a great question. I’m teaching Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton’s book Black Power, which was written in 1967—it’s a real critique of the betrayals and unreliability and arrogance of white liberalism as many in the black freedom struggle experienced it in the late 1960s, which helped produce this new politics called Black Power. So there’s a long history of this.

There are moments when white liberals might be open to the influence of social movements. I’m speaking here of white liberals with money and white liberals who are in the Democratic Party or otherwise have some governmental power. There are generally three reasons they become allies. One is they are afraid of the disruptive force of the social movement. Another is that they are afraid of the shame and guilt, of the international spotlight the movement puts on the contradictions or failures of American democracy. And then there might be some clergy who have a moral awakening, let’s say, that the movement sparks.

Those reactions can be mobilized by the movement to some benefit, whether it’s moving resources or passing some new laws. But this is a question that many are asking now, especially as segments of the movement try to influence the policy agenda of the Democratic Party, or they’re taking to the streets and creating disruptions that political elites have to face.

So it remains to be seen. The United States right now—we’re seeing in this election—is very polarized. We have this Right, and we have this revitalizing Left, hopefully, but we have a lot of work to do in the United States. A lot of work to do.

CM: Martha, truly a pleasure to have you on our show this week. Thank you very much for joining us today.

MB: Thank you. Take care.

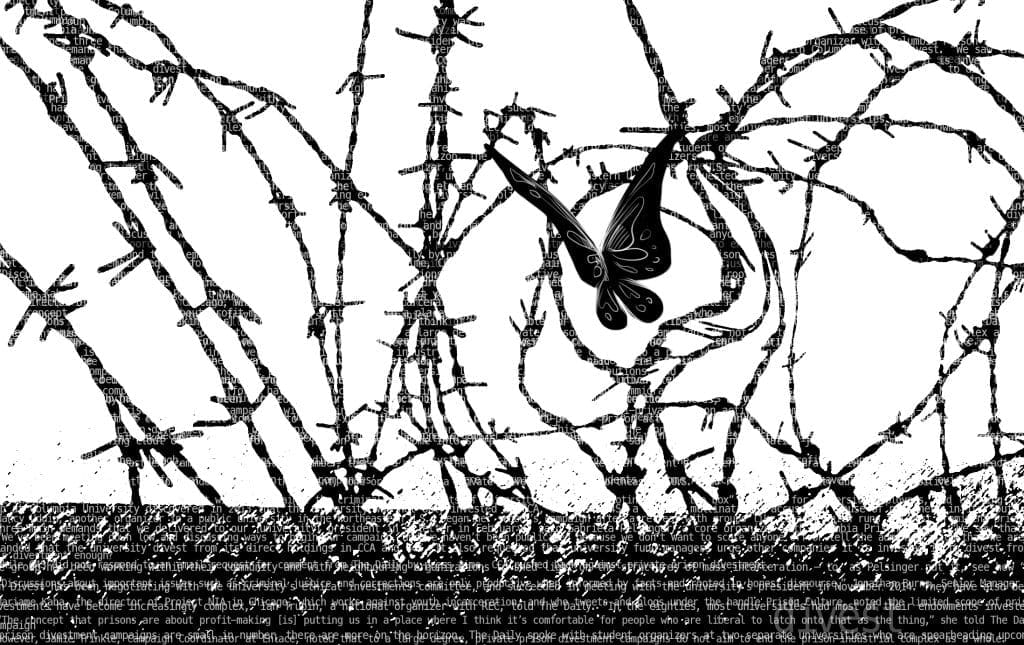

Featured image source: Black Lives Matter (Facebook)