AntiNote: Regrettably, it has been quite some time since we revisited the conflict in Ukraine (a failing in which we are not alone, though this fact provides no absolution). Friend of the Zine Gabriel Levy has been far more diligent at his blog, People and Nature, and we have nothing in particular to add to his contribution here, other than to encourage our readers also to view these findings in relation to the prison strikes still underway in the United States and consider new potential avenues of solidarity among the victims of crass authoritarianism, fascist violence, and enslavement worldwide.

Some link citations have not been reproduced. They can be found in the original.

Slave Labor in Lugansk: what war in Ukraine has “achieved”

4 October 2016

The separatist “Lugansk people’s republic” in eastern Ukraine is using five thousand prisoners as slave labor, a report by local human rights campaigners says.

The prisoners are caught in a legal no man’s land. Most of them were sentenced and jailed by the Ukrainian court system, which the “people’s republic” – established in May 2014 by armed separatists supported by Russia – does not recognize.

The prisoners are forced to work by violence, and the profits from what they produce are shared by the authorities of the “republic,” the report, published [in Russian] by the Eastern Human Rights Group (EHRG), says. The EHRG emerged from trade union organizing activity, and has campaigned for workers’ rights, both in Ukrainian-controlled territory and under the separatists’ rule.

Prisoners who refuse to work are first placed in solitary confinement for fifteen days, then denied visits and parcels from their families, and finally beaten and tortured.

The EHRG report includes interviews with prisoners who, when they refused to work, were severely beaten by armed, masked men; kept in solitary confinement with no food or water for three days; and forced by the threat of beating to stand eight to ten hours in the burning sun. In cases where prisoners have protested collectively, guards have called special detachments from the internal affairs ministry of the “republic” to attack them.

The prisoners work in joinery and metalworking shops and in food processing and other small production units. Some do odd jobs: repairs, kitchen work and the like. Some are paid five cigarettes per day; most are paid nothing.

The EHRG estimates, based on information from former prison officers and others, that revenues from products made by prisoners total from about $300,000 to $500,000 per month. They are appropriated by the leaders of the “people’s republic.”

The Ukrainian prison system was frightful enough before the Maidan events of 2013-14 that triggered the military conflict in the east. Torture and brutal treatment were common; badly-trained staff lorded it over prisoners, and there were very high levels of AIDS and other diseases. On the other hand, work was paid, and there had been efforts at reform.

Ukraine has 168 prisoners per 100,000 people, slightly more than the UK (England and Wales) with 146, but lagging way behind the world leaders, Russia with 450 and the USA with 693, according to the Institute for Criminal Policy Research.

It is war that has taken the Lugansk prisoners’ situation from bad to worse. Like another estimated eight to nine thousand detainees in the Donetsk “people’s republic,” they have no way of knowing if or when they will be released.

“The fact is that in the twenty-first century, in the part of the Lugansk region controlled by the so-called ‘Lugansk People’s Republic,’ slave labor is flourishing,” the EHRG report concludes. “About five thousand people work every day for nothing, in order to secure their life and health, to access visits from relatives and not to die from hunger.”

The context for slave labor is a war – ostensibly between eastern Ukrainian separatists and the Kyiv government, but in reality fueled by huge quantities of weaponry and volunteers that have poured over the border from Russia – that has cheapened human life and made torture, murder and forced disappearances the norm.

The corrosive effect of terror and militarization – which has continued this year, although the Ukraine conflict has disappeared from the headlines in other countries – has been detailed in recent weeks by:

Regular monitoring by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group;

An Amnesty International report on arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances and torture carried out by the Ukrainian army, Ukrainian irregular forces and the Russian-backed separatists;

A report by the International Partnership on Human Rights detailing seven murders, fifteen enforced disappearances, ninety cases of illegal detention, and 36 cases of torture and other mistreatment by the authorities in Crimea, which in 2014 was annexed by Russia. The report says that repression is directed particularly against the Crimean Tatar community, whose organizations largely opposed the annexation.

And a report on killings by all armed forces in the conflict by the UN Human Rights commissioner.

While civil society activists in eastern Ukraine endeavor to expose torture, slave labor and other such separatist “achievements,” those in Kyiv face a government that does little to conceal its contempt for its citizens who have been displaced to other parts of Ukraine by the conflict.

Internal affairs minister Arsen Avakov last week said that “refugee-migrants” from eastern regions to other parts of Ukraine were “sharpening the criminality situation.”

A group of activists and human rights campaigners, including Vostok-SOS and others who are supporting people who have fled the conflict zone, shot back that Avakov had no evidence that criminality was worse among internally displaced people (IDPs) – of which there are now an estimated 1.7 million in Ukraine. Furthermore, calling people “refugees” in their own country was a sign of Avakov’s “lack of professionalism” and “ignorance,” the activists’ statement said.

They were putting it very politely. Avakov was trying to stir prejudices between western and eastern Ukrainians – whereas, as the activists pointed out, all the evidence about worsening crime statistics suggests that they are linked to Ukraine’s social and economic crisis. That, in turn, has been aggravated by Russian support for separatist militarism.

Note from Gabriel Levy: Here is a thought for socialists elsewhere trying to follow the situation in Ukraine. In 2014, when the Yanukovich government was overthrown and Russia helped to turn the conflict in eastern Ukraine into a war, I published articles on People and Nature disputing the idea that the separatist (and/or the Russian state and armed gangs that supported them) were somehow furthering “anti-fascist” or “anti-imperialist” ends. (For example here, here and here.) Some people who made such ludicrous claims were less interested in what was actually happening in Ukraine and more interested in feeding some sort of geopolitical fantasy in their heads. They are probably off somewhere now talking about the “fight against imperialism” in Syria.

Well, reality is harsh. What has been “gained” by the separatist actions in Ukraine, and the heavy weapons and other support provided from Russia, is clear: slave labor, torture and arbitrary violence. The activists trying to piece together civil society and the workers’ movement in Ukraine deal with this every day. The least people elsewhere can do is to try more honestly to understand what’s going on.

GL, 4 October 2016

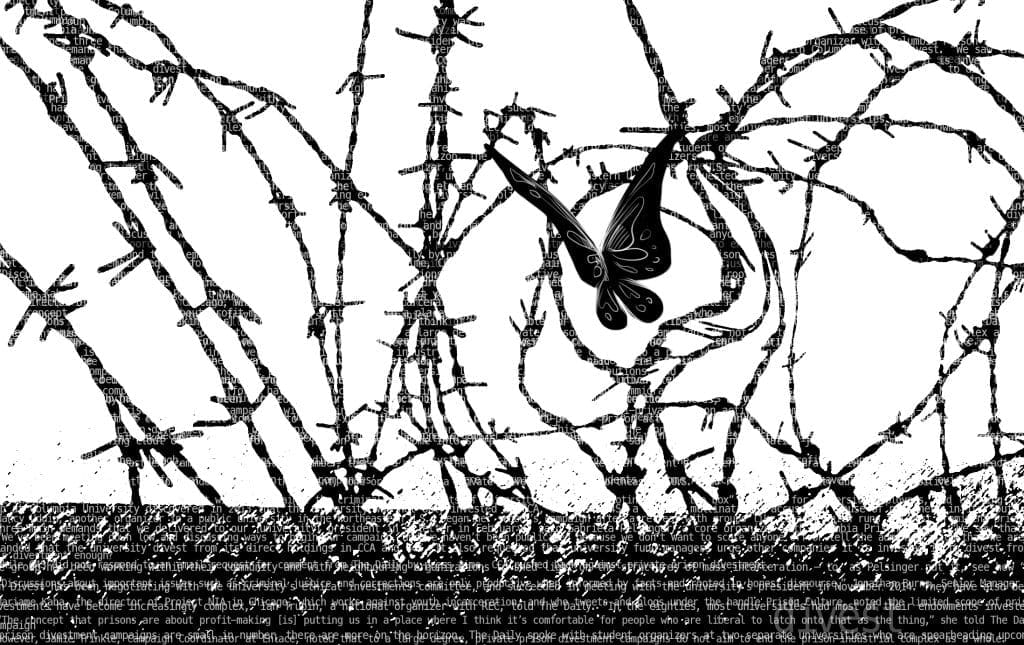

Featured image: Prisoners working at the Vakhrushevo penal colony in Lugansk. Source: Eastern Human Rights Group