Transcribed from the 28 October 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to to the whole interview:

The only thing that can displace a story is a story. You cannot take away someone’s story without giving them a new one.

Chuck Mertz: Neoliberalism has created greater disparity, furthered inequality, and destroyed our communities—and all just in time for the destructive effects of climate change. Here to explain just how unprepared we are for its worst effects, columnist George Monbiot is author of Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis. George’s most recent project is the album written with the musician Ewan McLennan called Breaking the Spell of Loneliness.

Welcome to This is Hell!, George.

George Monbiot: Thanks very much, Chuck, it’s great to be in hell.

CM: It’s great to have you on our show.

You write, “Drawing on experimental work, climate change communications expert George Marshall, author of Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change, shows that even when people have been told something is fictitious, they will cling to it if it makes a good story and they’ve heard it often enough. Attempts to refute such stories tend only to reinforce them, as the disproof constitutes another iteration of the narrative.”

So is the best way to combat fictitious claims just replacing them with a better story, rather than refutation? Is debating through storytelling more effective than refutation with evidence and facts?

GM: I’ve spent too much of my life arguing with climate change deniers who have a classic story, which says those so-called climate scientists are only in it for the money (as we all know how well climate scientists are paid), and they have created this conspiracy which is designed to hold us down and tax us and regulate us and stymie human freedom.

And I say to them, “Well, no, that’s not true. You can see these papers, and here are the facts and figures…” and it just bounces straight off. Completely useless. You’re getting nowhere at all. All it does is send them into further anger and reactive denial, because you cannot replace a story with facts and figures. The only thing that can displace a story is a story. You cannot take away someone’s story without giving them a new one.

CM: And you point out how there has to be a simplicity to the story. I want to talk about the two stories that you say are the most successful political stories of the twentieth century: the social democratic story, and the story of neoliberalism.

I’ll start with the social democratic story: you describe how it explains that “the world fell into disorder, characterized by the Great Depression, because of the self-seeking behavior of an unrestrained elite. The elites’ capture of both the world’s wealth and the political system resulted in the impoverishment and insecurity of working people. By uniting to defend their common interests, the world’s people could throw down the power of this elite, strip it of its ill-gotten gains, and pool the resulting wealth for the good of all. Order and security would be restored in the form of a protective, paternalistic state investing in public projects for the public good, generating the wealth that would guarantee a prosperous future for everyone.”

That’s the social democratic story, the Keynesian story we’ve pushed aside for the other story of neoliberalism. Why was the social democratic story pushed aside?

GM: There are a couple of reasons. First, it encountered various internal problems, such as stagflation and cost-push inflation, which led to economic crises. The second problem helps to explain the first one: throughout the Keynesian social democratic period, really from the end of the Second World War to the late 1970s, it was under sustained attack by global finance. Global finance managed to pull down many of the essential elements that made a Keynesian economy possible: capital controls, foreign exchange rates, a balanced global trading system. John Maynard Keynes was very clear: you couldn’t really have his system without those elements. And they destroyed those elements.

If we now try to use social democratic economics to boost incomes and employment by spending money back into the state, commissioning public services, putting money into people’s hands in doing so, thus stimulating manufacturing industry, which will create jobs, which will create income…if you pull that lever in the US now, then you’re creating jobs in China. Because the capital controls aren’t there, the foreign exchange rates aren’t there. With financially porous borders, Keynesian economics is very difficult to carry out.

Those two elements destroyed it, and then the neoliberals came along with their own story.

CM: Right. You write, “The neoliberal story explains that the world fell into disorder as a result of the collectivizing tendencies of the over-mighty state, exemplified by the monstrosities of Stalinism and Nazism but evidenced in all forms of state planning and all attempts to re-engineer social outcomes. Collectivism crushes freedom, individualism, and opportunity, the argument goes. Heroic entrepreneurs, mobilizing the redeeming power of the market, would fight this enforced conformity, freeing society from the enslavement of the state. Order would be restored in the form of free markets delivering wealth and opportunity, guaranteeing a prosperous future for everyone.”

But as you point out, both stories have the same outcome. That is, the ordinary people of the land would triumph over those who had oppressed them. How key is that to being the conclusion of whatever new story we propose or offer to the people instead of neoliberalism or social democracy?

GM: You’ll notice that they don’t just have the same outcome, but they have exactly the same narrative structure. I call this the restoration story. Disorder afflicts the land, caused by powerful and nefarious forces working against the good of humanity; the hero—it may be one person, a group of people, or may even be an institution—takes on those forces and, against all the odds, overthrows them and restores order to the land.

Keynesian social democracy is just not going to work in the 21st century, because it tries to stimulate a growth-based economy. When your economy keeps growing on a planet that is not growing, it bursts through environmental boundaries, and that’s what we’re seeing happening worldwide.

This is the basic narrative structure I call the restoration story, which has prevailed for centuries and centuries. It’s been key to many of the world’s most successful political and religious transformations. It’s one of those stories for which our minds are already prepared. We’re ready to hear that story.

Human beings have a very powerful narrative instinct. We tend to navigate the world through narratives because we can’t do it through facts and figures. It’s simply too complicated to try and work everything out by asking, “What does the data show me about what I am seeing?” We just can’t survive that way. We have to use a shortcut, and the shortcut we use is story, narrative.

We have a strong evolutionary predisposition to listen for stories that tell us who we are, where we are, how we got here, and where we’re going to go next. There are particular stories that resonate strongly with us, and work again and again. In politics and religion, it’s the restoration story which always seems to come out on top.

The question I’m asking is: Why, despite its multiple and manifest failures, are we stuck with neoliberalism? When Keynesianism hit the rocks, neoliberalism came along and said, “We’ve got the answer,” and everyone became neoliberals, when everyone was a Keynesian before. And then neoliberalism hit the rocks spectacularly in 2008—and all the other crises which it caused were exposed by the financial crisis: the economic crisis, the crisis of inequality, the political crisis, the environmental crisis, social crises, mental health crises. They were all caused or exacerbated by neoliberalism…but it’s still here! It’s still the dominant force in our lives.

The reason why is that we have not produced a new restoration story with which to replace it.

CM: Whether the neoliberal story or the social democratic story are both narratives our attempts, maybe even clumsy attempts, to better understand our relationship with capitalism? To make sense of our lives within the current form of capitalism? To give our lives meaning within capitalism?

GM: They have quite different origins, really. The social democratic story had deep roots in the reaction to the extremely greedy behavior of nineteenth century industrialists and the robber baron economy which had caused such massive problems for so many people around the world. When John Maynard Keynes, in response to the Great Depression, sat down to come up with a whole new approach to economics and wrote his General Theory, that was building on the work of many social thinkers over decades and decades.

The neoliberal story came about rather differently. The first use of the word neoliberalism was in a colloquium in 1938, but it really began to congeal in the works of Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, who both published books in 1944 (The Road to Serfdom and Bureaucracy), and then Hayek set up this thing called the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947. That became a sort of neoliberal International. Some very rich people poured money into the Society and then set up think tanks, sponsored academic departments, recruited journalists, and recruited government policy advisers. It was an elite project from the beginning.

It was basically sponsored by the ultra-rich—some of the richest people in the world at the time—who kept the whole thing under the public radar. It wasn’t something which was widely discussed. Lord Keynes came straight out, everybody started discussing his ideas straight away, and they very quickly began to soak into the political fabric. In this case, however, Milton Friedman, one of the leading neoliberals, basically said, “We just had to wait, because we could see that Keynesianism was going to last a long time, so we would just bide our time, build up our networks, build up our financial resources, and when the time comes, when the current system falls into crisis, we will sweep in with our story.”

Which is exactly what they did. And in fact Friedman’s prediction of how that crisis would occur was uncannily prescient.

CM: You write, “Competition and individualism are the values at the heart of the 21st century’s secular religion. Everywhere, we are encouraged to fight for wealth and social position like stray dogs over a dustbin. Competition, we are told, brutal as it may be, will enhance our lives to a greater extent than any other instrument. This story is supported by a rich mythology of rugged individualism, and advanced through an inspiring lexicon of lone rangers, soul-traders, self-starters, self-made men and women ‘going it alone.’ The word people has been widely replaced in the media by the word individuals.”

How much do you think people realize this is a false religion? Has it become more fundamentalist? Is this being pursued more zealously than ever, or do you see signs that people are backing away from this story?

It is very striking: a lot of neoliberal economists are highly selfish and greedy people who really aren’t typical, but they think that they represent the human norm.

GM: We’re seeing several things happening all at once. First, those who were exposed by the crisis of 2008, the great supporters of the neoliberal narrative, seeing that no one was coming up with a coherent challenge to them, doubled down on their narrative and responded to the crisis with neoliberal austerity, further controls on trade unions, further tax cuts for the rich, further deregulation, the whole neoliberal agenda. They just intensified it.

Other people recognized, as many now do, that this philosophy has been a catastrophe for human beings and for the rest of the living world, and are desperately casting around for some response to it. Unfortunately, in most cases the response has been to try to reclaim some form of Keynesian social democracy, and it’s just not going to work in the 21st century, partly for the reasons I’ve already mentioned, but also partly because it tries to stimulate a growth-based economy. When your economy keeps growing on a planet that is not growing, it bursts through environmental boundaries, and that’s what we’re seeing happening worldwide at the moment, with climate breakdown, with the loss of soils, with mass extinctions, with air pollution, and so many other crises that we’re facing as a result of perpetual economic growth. We really need a new system.

But the third response has been to say politics just isn’t working for us. Part of the neoliberal approach is that you shouldn’t do things through politics, you should only do things through the market; politics is dead. And if politics is dead, then people can’t pursue any political solutions within democracy. So they choose to follow someone who is outside of politics, someone who isn’t part of the usual political establishment, and someone who tells us that we can triumph once more. We then get the election of demagogues and fascists, Donald Trump certainly being an example of the former.

We’re seeing fascists rising in one form or another all over the world at the moment, and this is a response to the political failure caused by a doctrine which says that government should step out of the way, there shouldn’t be any effective political response, government should not try to change social outcomes. People then see themselves falling into disaster and they say, well, government isn’t helping us, we need someone who’s completely different from any government we’ve ever seen before, and that someone is a fascist or a demagogue.

This is a very dangerous age, and it’s because we have failed to produce a compelling, positive, and inspiring restoration story with which to replace the failed story of neoliberalism that we see the rise of fascism. This isn’t just a nice thing we might do. This is an urgent quest to find a story which fills the gaping hole, the vacuum into which the fascists are stepping. If we want to stop fascism from repeating what happened in the 1930s, we urgently need to tell this new restoration story.

CM: You talk about how we have redefined ourselves into something that is a fiction. You write, “Many economists insist that we are typically selfish and self-maximizing. They use a term to describe this perception of humanity that sounds serious and scientific, homo economicus. Most of them seem to be unaware that the concept was formulated by John Stuart Mill and others as a thought experiment; soon it became a modeling tool, then it became an ideal, then it evolved into a description of who we really are. But we don’t act like homo economicus.”

How much of the failure of neoliberalism, the failure that capitalism is facing right now, is due to the conflict between the system assuming we are homo economicus and the fact that we do not act that way?

GM: Neoliberalism, at heart, is a description of human nature. It’s much more than just economics. It basically says we are selfish, we are greedy, we are ultra-competitive, we are ultra-individualistic—and that we should see these characteristics as good things and harness them, because that will mean that some people will become extremely rich and their wealth will trickle down to enrich everyone.

The first thing to say is that there’s no scientific evidence whatsoever for their view of humanity. All the scientific evidence—and there’s been a great deal produced in the last twenty years, in neuroscience, in psychology, in anthropology, and evolutionary biology—suggests that we are spectacularly altruistic in comparison to other animals. We all have a bit of selfishness and greed in us, for sure. But our values are overwhelmingly dominated by altruism, by empathy, by benevolence, by community feeling, by kindness towards others.

Unfortunately, again and again (and this holds true across centuries), we tend to allow people to dominate us who don’t share those values at all. Our leaders typically have a completely different set of values, Donald Trump being the classic example. His values could be characterized as a great desire for self-enhancement, for more money, more fame, more status, more image. We see people like that, and we think that’s what human beings are like, because they’re the ones we see in the news all the time. But it’s simply not.

The evidence is very strong that people don’t behave that way. We behave very kindly towards others as a default. Obviously there are some people who don’t, and their default response is really extremely destructive and selfish and greedy, but they’re a small minority. Unfortunately, neoliberalism has told us that is how people are and how they should be. It is very striking (and there’s been quite a lot of work on this, too): a lot of neoliberal economists are like that themselves. They are highly selfish and greedy people who really aren’t typical, but they think that they represent the human norm.

This isn’t just a nice thing we might do. This is an urgent quest to find a story which fills the gaping hole, the vacuum into which the fascists are stepping. If we want to stop fascism from repeating what happened in the 1930s, we urgently need to tell this new restoration story.

Neoliberalism says this is how people are, and this is how they should be, so let’s build a world around this idea, and let’s ensure that there is no impediment to inequality, because inequality is what drives people to want more wealth, and the more wealth there is, the richer everybody will be. They have all these justifications which actually lead us towards disaster. And they lead to some people being able to accumulate billions while other people starve.

This whole myth that the trickle-down economy—created by an attempt at self-enhancement and self-enrichment by those who can elbow their way to the top—is a benefit to everyone is just patently untrue. What we get instead is a situation of patrimonial capital where those who are rich already (once the brakes are taken off, when there’s no effective trade unions, taxation, regulation) are able to become stupendously rich and then pass that wealth to their children, who use it to gain political power and become even richer themselves. It bears no relation, in the end, to any form of hard work, or to merit, or to anything like that. The age of enterprise is actually the age of rent.

CM: After arguing that our original virtue is that we are altruistic, but that something has just gone wrong, you write that this leads us to a disorder—and that this disorder is loneliness. “An epidemic of loneliness is sweeping the world. Once considered an affliction of older people, it is now tormenting people of other generations.”

How does our altruistic virtue tolerate loneliness? And how does neoliberalism exacerbate loneliness?

GM: Loneliness is one aspect of alienation. We live in the age of alienation, where we are alienated from ourselves, alienated from other people, alienated from the natural world, and alienated from our work. The most visible aspect of this is loneliness, which is a devastating condition. People who are chronically lonely are as much at risk of ill health as diabetics and people who smoke fifteen cigarettes a day, and they’re twice as likely to suffer ill health as people who are obese.

The reason for that is loneliness is strongly associated with production of the stress hormone cortisol, which lowers the immune system. It also has devastating mental health implications. It was while researching for the album with Ewan McLennan that I came across all this work on what human nature really is, and the way in which we’ve been effectively conned about who we are and what we’re like, and read these papers showing how remarkably altruistic and empathetic we are. I thought, wait a minute, there’s a politics here.

There’s a politics to be built on this. There’s a whole new story. There’s a restoration story to be built around these scientific findings. This is really exciting. That then led to the current book, Out of the Wreckage, to turn that into an effective restoration story and a politics which we can work with.

CM: How much damage has neoliberalism done to the chance that we may embrace any kind of universal well-being? You talk about how it isn’t the social democratic story that we should be following and it isn’t the neoliberal story; it’s something outside of that story, it’s something that is in the commons that has to do with community. But how much damage has neoliberalism done—and how much damage does it continue to do—to make us not want to pursue a cooperative solution?

GM: It’s still the case that our values are dominated by altruism, empathy, and community feeling. But the selfishness and greed are more powerful than they used to be. They’ve been bubbling up more and more. There’s some other very interesting work by social psychologists showing that we absorb and internalize the dominant values of the politics that we face. If you’re in a country where people are allowed to fall through the cracks and basically starve to death, where the rich can take whatever they want, and powerful people can trample powerless people, you tend to become more selfish yourself. Your values shift towards seeking wealth and fame and image and status, because you start looking out for Number One.

If you live in a country with strong social safety nets, where there’s a sense that everyone is cared for, and there’s a strong sense of community, your values shift sharply towards becoming even more altruistic, empathetic, and benevolent. We internalize this. This is part of the reason why I believe that this new restoration story has to be based around community and belonging, because of the dramatic impact that those things have on our own psyches, and the way that they reveal the better aspects of our nature.

CM: When the Labour party was predicted to be wiped out in parliamentary elections, you said that if the party took the tack of Bernie Sanders and his grassroots mobilizing, then Labour had a chance. That’s exactly what they did, leading to a much closer than expected outcome, with Labour greatly expanding its base and the Tories losing their majority. That’s the big organizing model that you talk about. And you believe that we can have a new kind of politics that protects the environment by using big organizing like Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn did.

How much more ready for change is the world than we may think? The Democratic Party certainly wasn’t ready for Sanders, and Corbyn was originally mocked for being too far left by even those within his own party. How tired is the world of centrism? And are we far more ready for change than people may realize?

We’ve got huge numbers of people who are ready to commit themselves to a better, kinder, more generous, more inclusive politics. At the community level, we’re seeing a resurgence of volunteering around the world: loads of people wanting to make their communities better, volunteering for community projects, setting up community projects.

GM: I believe so. Part of the problem that we face is that the mainstream media in any nation gives us a distorted view of how we’re thinking. In my country, the UK, almost all the newspapers are owned by billionaires. And the billionaires try to create a world which works better for them, which tends to be a world that works worse for the rest of us. They are constantly giving us a distorted picture of who we are and where we stand.

One of the things that they’re trying to persuade us of is that we’re inherently very conservative. But we’re not. At the moment, worldwide, there are people seeking a better way, a better politics. My argument is that if we can take something like the Corbyn campaign or the Sanders campaign—with their very interesting new forms of organizing and mass mobilization (generally by young people) on the basis of volunteering, the big organizing model which the Sanders campaign really pioneered—and we can marry that with a new restoration story, a story which explains that we are a good-natured creature which has been thrown into disorder by an outrageous ideology that’s been imposed on the world, we can rebuild. We can bring the land back to order.

We, the heroes of the story, through building community, through building a sense of belonging, shift the economy away from the market, away from the state, and into the commons—and build a system that’s not capitalist, that’s not communist, it’s an entirely different kind of economy. Resources are owned by communities, run and managed by communities and for communities, and where the products of those resources are shared equally among the communities, then we can expose the better aspects of our nature.

We can become the people that we really are. We can restore order to the land that way. What I’m telling is a restoration story. If we can marry it with a new way of doing politics, we will become unstoppable. We have the story. We have the new way of organizing. Put those two together, and we will sweep the world.

CM: You call this the “politics of belonging.” You also talk about “organizing self-motivated networks of volunteers using the wisdom of crowds to refine and enhance new political techniques. We mobilize a force that the power of money can never match, mutual aid operating on a grand scale.”

What do you mean by “using the wisdom of crowds”? And why are you so confident that crowds would participate? What we’ve been taught under neoliberalism is that people don’t have time for democracy.

GM: I come at this from two different angles. One of them is seeing what happened with that giant live experiment called the Bernie Sanders campaign, where he started with three percent name recognition, almost no money, almost no staff, and thought, “The only thing we’ve got is people’s enthusiasm. What if we can give some staff jobs to volunteers?” They found it worked, so the first wave of volunteers trained the second wave of volunteers, and by the time the nomination process closed, they had a hundred thousand volunteers working for them who had organized a hundred thousand events, and spoken directly to 75 million Americans.

That was just the experimental phase of trying out this new model. They cracked it, really. They got to understand how to do it right by the end of the process. They admit that they missed. Same with Corbyn: they only had six weeks to mobilize, because the election timetable is so short here. But again, they very nearly clinched it. And this model is still in its infancy.

So for a start it’s very clear that we’ve got huge numbers of people who are ready to commit themselves to a better, kinder, more generous, more inclusive politics. But also, at the community level, we’re seeing a resurgence of volunteering around the world: loads of people wanting to make their communities better, volunteering for community projects, setting up community projects. Very large numbers of people are now engaged in this, and are often doing a much better job of restoring civic life and restoring local services than governments are doing.

There is real wisdom of crowds here, and there is a real political community beginning to develop alongside the geographical community. This is what gives me hope and what tells me that the new restoration story based around community and belonging actually has a chance of flying.

CM: One last question for you, George, and as we do for all of our guests, it is the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

Writer Keith Koffler has a biography coming out in mid-November called Bannon: Always the Rebel. The publisher says that former Trump aide and Breitbart owner Steve Bannon gave Koffler ten hours of interviews for his book. Bannon is quoted as saying, “Populist nationalism is the winner of what we’re doing now. It’s on the right side of history. The only debate going forward will be whether it will be British Labour party leader Jeremy Corbyn’s and Bernie Sanders’ views of populism or Donald Trump’s view and Indian prime minister Modi’s view of populism—whether it will be culturally right and economically conservative or whether it will be socialistic.”

Do you agree with Steve Bannon that we are about to choose between one of two stories, the story embodied in Trump and Modi and the story embodied in Corbyn and Sanders? I just wanted to make you agree with Steve Bannon on something, George.

GM: Thank you for that invitation, Chuck, but I must decline. Much as I greatly admire both Corbyn and Sanders, the story they told during their election campaigns was quite an old story. They tried to go back to 1970s social democracy. We need to tell a new story.

I don’t know about the Democrats, but Labour in the UK knows that now. They are aware that it has to be something completely new, and they’re casting around for new political and economic ideas. I’ve been talking to them and I hope to continue doing so, and I hope they might pick up something similar to the new story that I’m trying to tell.

I wouldn’t call it populism, I would call it an insurgence of a powerful new political idea into which a whole new politics and economics can be embedded. It’s similar, in a way, to that Keynesian moment at the end of the Second World War, where we saw a new philosophy and tried to do something very interesting and transformative with it. We don’t need a Bannon-style populism to do that. We need to create a new common sense.

That new common sense is to recognize what extraordinary altruistic creatures we are, and to build a politics around that.

CM: George, it has been a pleasure having you on our show. Thank you very much.

GM: Thanks, Chuck.

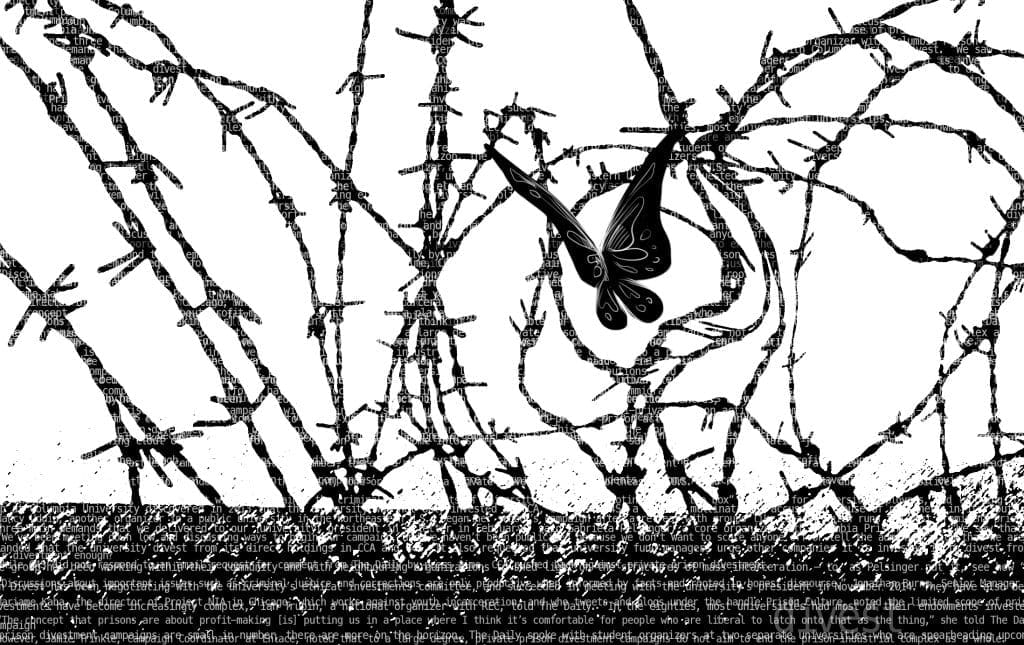

Featured image source: Kick It Over