Transcribed from the 9 December 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

We can go all the way back to the inception of the FBI to understand what kind of a “law enforcement” organization it is. It is a political police. It is the government’s political police.

Chuck Mertz: Fred Hampton’s assassination a little more than forty-eight years ago still has rippling effects to this day, as the shockwaves from that killing still resonate with black liberation movements. Here to tell us about the murder and what it means for today’s activists, attorney Flint Taylor posted the Truthout article this week “On Forty-eighth Anniversary of Fred Hampton’s Murder, Rampant Surveillance of Black Liberation Movements Continues.”

Flint, welcome back to This is Hell!.

Flint Taylor: Great to be back again, Chuck.

CM: You write, “In August 1967, notorious FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sent out an urgent directive to all of his field offices under the file name COINTELPRO – Black Nationalist Hate Groups. It instructed ‘racial matters’ [RM] agents to take aggressive—and highly illegal—actions to ‘expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize the activities of Black-nationalist hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters.’”

But, Flint, what laws did Hoover believe black liberation movements were breaking? And if the FBI didn’t believe the movement was breaking any law, what does that say to you about the real role of the FBI in 1967—and potentially today—other than law enforcement?

FT: We can go all the way back to the inception of the FBI to understand what kind of a “law enforcement” organization it is. It is a political police. It is the government’s political police. It was founded by Hoover, before he even became the head of the FBI, when he was in charge of the justice department and their notorious Palmer raids back in 1919 and 1920; then it morphed into the FBI. Soon thereafter, as the “communist and socialist threat” and the “black nationalist threat” became things the government wanted to suppress and destroy (or “neutralize,” as the term may be), they moved into this program called COINTELPRO, or counterintelligence program.

From its inception it has been secret, it has been illegal, it has been unconstitutional, and I suppose (with an altruistic view of what America is) it’s un-American.

CM: When people think of the Black Lives Matter movement, they think of it as a movement that is opposed to police abuse. Do you think that the Black Lives Matter movement should also target reforms at groups like the FBI—if not support the abolition of the FBI, as many support the abolition of the police?

FT: I have a tremendous amount of respect for Black Lives Matter and Assata’s Daughters and BYP100 and all of the organizations under the umbrella of the current black liberation struggle. Can we look at the murder of Fred Hampton and all the history I just mentioned in the lens of today? Yes. Back in the sixties when they were targeting Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and then Fred Hampton and the other Panthers, to destroy the Black Panther Party and other organizations, they had the same kind of terminology, the same kind of approach that we now see they have today with the release of this odd FBI counterinsurgency report that we just heard about, where they now call the successors to those same organizations “black identity extremists.”

That’s what this report talks about. It talks about identifying them, and makes the broad statement that the “black identity extremist movement,” whatever that may be, was behind a half dozen shootings of cops around the country over the last couple of years. They’re trying to identify and surveil and target the kinds of organizations that were fighting against police violence and racism today in the same way or similar to what they were doing back in the sixties and seventies. That’s what’s really striking and chilling about this new report.

CM: If people think that it can’t happen today: it’s already happened. But people might not be aware that it happened in the past with Fred Hampton.

We’ll get back to Fred Hampton in a moment, but in that memo, they talk about the shooting of Michael Brown leading to a whole bunch of attacks on police across the country. What evidence is there that the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson led to violent and deadly blowback against the police across the United States?

FT: This is only a ten page report. But the attitude of the FBI—in terms of implicit racism—is paramount in the language on those ten pages. They talk about the “alleged” shootings, the “alleged” racial content of the killings of Michael Brown and all of the other young men and women of color across the country in the last few years. That’s all “alleged.” But all of the sudden, it’s “very, very likely,” in their own terminology (and they even have a definition of “very, very likely.” It’s ninety percent sure, in the FBI’s mind), that these six different shootings of cops by African-American men across the country in the last two years were in retaliation for the vicious killing of Michael Brown and the ones in Minnesota and all the rest.

They link all that together into something called the “black identity extremist movement” which then gives them the opportunity to surveil whomever they put in that category. There’s no definition of that category, so we have to believe that they’re doing the same thing that they did back then. All organizations that are anti-police, in the sense of dealing with police brutality—characterizing it as racist, characterizing it as a system—are in this catch-all category of black identity extremists, and supposedly their ideology, whatever that is, caused all these different shootings in Dallas and New York and elsewhere.

It’s totally ridiculous, on a certain level. But it shows you what their thinking is, what their racial approach is, and what their continued focus on being the political police really is about.

CM: Let’s talk about the language of the FBI report. It is just amazing, what it says: “The FBI assesses it is very likely incidents of alleged police abuse against African-Americans have continued to feed the resurgence of ideologically motivated violent criminal activity within the black identity extremist movement.”

But this is the part that freaks me out: “The FBI assesses it is very likely some black identity extremists are influenced by a mix of anti-authoritarian, Moorish sovereign citizen ideology, and black identity extremist ideology.” Moorish? How much do you see clear racism within that statement?

FT: The whole report is racist. They go on to identify what they perceive as the “Moorish movement.” Apparently there is some historical grouping that (at least they say) identifies that way. I certainly am not aware of it. That doesn’t mean such an ideology doesn’t exist in some form. But I certainly wouldn’t trust the FBI saying that it exists, or what its ideology is, or how it applies to the greater movement in general—or how, if at all, it applies to these disparate killings of cops around the country.

Sessions testified about this report a few weeks ago on the hill, and there was an African-American congresswoman named Karen Bass who grilled Sessions on it. You can just picture Kate McKinnon (I can’t think of Sessions without thinking of her on Saturday Night Live playing Sessions) playing dumb about this report, going, “Hmm, this sounds interesting, I’d like to know more about it.”

So we not only have the FBI coming up with the new version of the “black nationalist hate groups” terminology of the sixties under COINTELPRO, but we’ve got the justice department paralleling Mitchell and Nixon’s justice department in the sixties and seventies, ramping up to implement and give cover and prosecute on the same theoretical political basis as the political police that we saw back in the Hoover and Mitchell days. Sessions, and this FBI, have their reins completely loosened by the Trump administration and are gearing up to do similar things to what we saw in the sixties and seventies.

CM: Getting back to the assassination of Fred Hampton, you write, “On December 4, 1969—forty-eight years ago—RM agents in the FBI’s Chicago office secretly congratulated themselves and hailed their ‘success’ to Hoover for masterminding the bloody predawn police raid that left Fred Hampton, the 21-year-old chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party—and most certainly a rising ‘messiah’—and Peoria Panther leader Mark Clark dead and several other young Panthers seriously wounded.”

What do you think the FBI feared about Fred Hampton, or about people like Martin Luther King? How much do you think this was a violent reaction to a sense that white privilege and supremacy were being challenged?

FT: Let me say one thing about that quote you read, about the term “messiah.” The second of the documents that Hoover sent out, only one month before Martin Luther King was assassinated, said that all the field offices needed to come up with COINTELPRO “aggressive actions” to prevent the rise of a “messiah who would electrify the black nationalist movement.” So when I use that term and say Fred Hampton was a young “messiah,” I am using that terminology not just in its general sense but in the sense the FBI used to categorize Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, as well as Fred Hampton when he came along as this remarkable 21-year-old leader of the Black Panther Party.

They saw the Panthers as one of the greatest threats to the internal security of the United States, and they said so. Why was that? It was for several reasons. On the one hand it was because of their revolutionary rhetoric; they said to defend yourself against the police. There was rampant police brutality then as there is now, and the Panthers were doing something about it: “We’re going to arm ourselves; we’re not just going to get shot down in the street. They come at us, they come at our community, we’re going to fight back.”

We changed the narrative from it being a shoot-out to it being a shoot-in; we established the truthful narrative that Fred Hampton was murdered, that he was assassinated as part of the COINTELPRO program.

That obviously was seen as a threat, but even more important, perhaps, were all the socialist programs the Panthers were implementing. They had a breakfast program for children where a lot of hungry kids on the West and South Sides would be fed before they went to school. They had a health clinic (one of the people in the apartment where the raid took place was a tremendous young man by the name of Doc Satchel; Doc was the head of the Panther medical clinic).

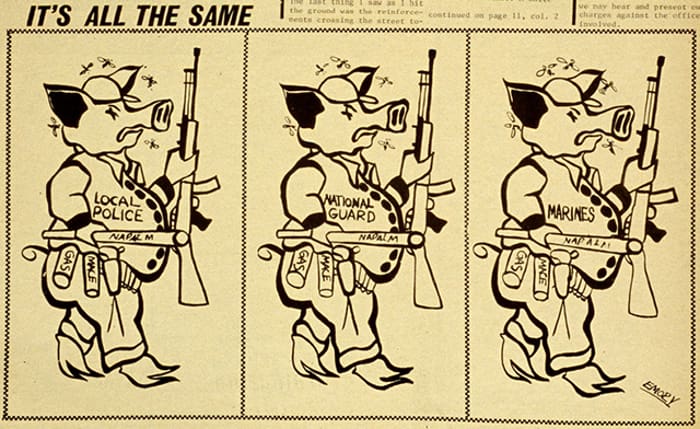

They had a newspaper. The newspaper talked about the pigs all the time—the pigs of course were the police—and they had a tremendous cartoonist named Emory Douglas. Every week they’d come out with a paper, they’d circulate it around the country, they’d sell it for a quarter on the streets; their people would get busted all the time because the police and the FBI didn’t want Panther propaganda on the streets. These papers always had wonderful cartoons with pigs, and current affairs would be put into cartoon form as well as written up.

They had liberation schools as well. They were teaching young people their ideology. They had a rainbow coalition: they were bringing together the Young Lords, the Young Patriots, the SDS—different races, different political ideologies—and they were also trying to bring the street gangs out of their violent-prone attitudes within the community and embrace the Panther ideology. That’s why the FBI and the police saw them as a major threat that had to be, in their own terminology, “neutralized and destroyed.”

CM: But none of that was illegal. You’re not supposed to be able to arrest somebody for selling a newspaper.

FT: They would arrest them for disorderly conduct. There would be raids. And as I said, if the police came around and fired into the Panther offices on West Madison Street, the Panthers would fire back. Then there’d be a shootout, Panthers would be either shot or arrested, and then the police for good measure would bust into the Panther offices and set the food and the papers on fire. It was an amazing period of time, and a lot was going on.

In December of ’69, the COINTELPRO program went into high gear. They had an FBI informant in the Panthers named William O’Neill, and he crafted a floor plan showing where Fred Hampton would be sleeping. The FBI then relayed it to the Chicago police and the state’s attorney of Cook County, Edward Hanrahan, also part of the COINTELPRO program, and at 4:30 in the morning fourteen cops rode to bear with machineguns and shotguns and pistols, went into the apartment, fired about ninety-five shots at the Panthers, and Fred Hampton was shot in the head twice while he lay asleep in the back room.

CM: And as you write in your article, he may have been drugged by the FBI undercover agent, is that correct?

FT: We went to trial for eighteen months on the Fred Hampton case several years later, and during that trial we uncovered a lot of evidence that proved that the FBI was involved. One of the interesting issues was whether Fred Hampton was drugged. We had an independent toxicologist who tested his blood after his death, and they found a large amount of secobarbital in his system. Everybody knew that Fred never did drugs, so that established that he was drugged.

The evening before, the FBI informant, O’Neill, had given Fred some Kool-Aid and some hotdogs to eat. The theory as we understood it was that O’Neill drugged him. But the federal government did another test, and lo and behold: they said our toxicologist had made a mistake, that she didn’t use the right kind of equipment. In that sense, it’s been proven—but it’s also not surprisingly been contested by the FBI, and we had a big battle about that in our trial.

But he definitely did not wake up. And he was not killed in the first wave. Many Panthers were brought out of their rooms wounded and bleeding—he wasn’t. Then the Panthers heard the cops say, “He’s barely alive; he’ll barely make it,” and then two shots rang out, and the cops said, “He’s good and dead now.” And there were two bullet holes in Fred Hampton’s head.

CM: The police said at the time that the raid of Fred Hampton’s home was a shootout between the Panthers and the police. An inquest later determined that it was a justifiable homicide. Yet you continued with a $47 million civil rights lawsuit that the family brought, and you would later settle for $1.85 million. You were quoted saying the settlement was an “admission of the conspiracy that existed between the FBI and Hanrahan’s men to murder Fred Hampton.” However, assistant United States attorney Robert Gruenberg claimed the settlement was intended to avoid another costly trial and was not an admission of guilt or responsibility.

So how much was justice served if the US attorney says it was not an admission of guilt, and if you got $1.85 million instead of the initial $47 million?

FT: That’s a complicated question. The short answer is that we fought the case for thirteen years. I went to jail; my partner, Jeff Haas, went to jail for contempt to try to uncover all of the FBI documents. Those documents weren’t handed over to us, we had to fight for them to show that the FBI was involved. We had a judge who was a total Alabama racist, and after eighteen months of trial, he threw the case out and we had to go to the seventh circuit court of appeals, where we got a remarkable decision which held that we had put on very strong evidence of a conspiracy to destroy the Black Panther Party and that we deserved a second trial. At that point we had been in litigation for ten years.

It went to the US supreme court, and we were able to persevere there. Then it came back to a different judge in Chicago in the early eighties, and at that point our clients and the Hampton family felt that through those decisions we had established definitively what had happened. We had changed the narrative from it being a shoot-out to it being a shoot-in; we had established the truthful narrative that Fred Hampton was murdered, that he was assassinated as part of the COINTELPRO program. We felt that we had accomplished a great deal at that time. At that point, rather than go back to trial, we took the settlement—which of course in this day and age doesn’t look like that much money, but it was the largest settlement in the history of civil rights cases at that time. So we felt that through thirteen years of struggle we had accomplished a great deal.

Now, none of these murderers went to jail. Mrs. Hampton, Fred’s mother, always felt (and quite rightly so) that that would have been real justice, so in that sense we didn’t establish complete justice by any stretch of the imagination. But we did change the narrative. We were able to rewrite history through the courts and through the streets and through the evidence we were able to uncover, to change the narrative, to tell the truth about what happened. In that way, US attorney Gruenberg can say whatever he wants. Whenever you settle a case they always say there’s no admission of liability, but you just have to look at the entire record and make the decision for yourself about who won and who lost and what was accomplished.

CM: One of the partners in your lawsuit, a person you just mentioned, Jeffrey Haas, wrote in his book The Assassination of Fred Hampton on the legacy of the killing: “Without a young leader, I think the West Side of Chicago degenerated a lot into drugs, and without leaders like Fred Hampton I think the gangs and the drugs became much more prevalent on the West Side. He was an alternative to that. He talked about serving the community. He talked about breakfast programs, educating the people, community control of police. So I think that’s unfortunately another legacy of Fred’s murder.”

How much do you think the problems of Chicago’s West Side still to this day were caused by the police assassination of Fred Hampton that was coordinated by the FBI?

FT: There are a lot of factors that go into the present condition in the African-American community, and I’m certainly no authority on that. But as I did in my prior answer, I’d prefer to look at the more positive aspects. In the Hampton case, they finally did indict the cops and the state’s attorney of Cook County, Ed Hanrahan, by a special prosecutor, but a machine judge threw the case out on the eve of the 1972 election (Hanrahan was running for re-election). The black community was so outraged by that that they switched over and voted in a Republican. That formed a movement in the community that later led to the election of Harold Washington as mayor, and to some degree that movement had an impact on the election of Obama. In that sense you could see a positive impact on the community, and that would be something that I would focus on more than what Jeff mentioned in his book.

CM: Flint, I love you brother. Thank you so much, I’ll talk to you in a couple weeks.

FT: Okay, take care.