The world to Syria: “Just stay in your country and die.”

Nine Years of War in Syria

Interview with Leila al-Shami

by Merièm Strupler for Die Wochenzeitung (Switzerland)

12 March 2020 (original post in German)

How the uprisings in Syria became a war, why there is so little Western interest in the humanitarian crisis, and why she is disappointed by the Western left: a conversation with Syrian-British author Leila al-Shami.

Merièm Strupler: Leila al-Shami, last week you wrote on Twitter: “The West doesn’t care about Syrians dying in Syria. But as soon as refugees start reaching Europe’s borders watch the world go into full on crisis mode.” Do you think that’s hypocritical?

Leila al-Shami: Definitely. For refugees, the crisis doesn’t start at the European border, but already in Syria. So that’s where the solution to the crisis has to start too. Since December, people in Idlib province have been driven from their homes in droves—and the Syrian-Turkish border is closed. If Idlib falls, there could potentially be three million refugees.

The regime of Bashar al-Assad and the Russian air force are responsible for the vast majority of the dead, the destroyed cities, and the displacement. There were two ways the West could have protected the population, but it did nothing. There could have been a no-fly zone, as Syrian civil society had called for; or at least refugees could be offered safety. But the message to the people in Syria seems to be: just stay in your country and die.

MS: Before Russia and Turkey agreed to a ceasefire last Thursday, the situation in Idlib had escalated…

LS: The situation in Idlib may have changed dramatically from a Western point of view, but less so from a Syrian one. For civilians on the ground, the Turkish intervention at the end of February provided a break from relentless bombing by the regime. But Syrians don’t have any illusions about this. Turkey is pursuing its own goals: first it wants to create a so-called buffer zone in northern Syria to send Syrian refugees back to from Turkey. Second it is acting against the autonomous self-government of the Syrian Kurds near the Turkish border.

MS: At the beginning of March, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced he would open the border to the EU. Since then the situation on the Greek-Turkish border has also escalated…

LS: Erdoğan is using the refugees’ plight to get European Union support for his military operation in northern Syria. In doing so he is putting people in grave danger: on the Greek side the border is still closed, and they are shooting at refugees. It is completely cynical. Almost a million people in Idlib have had to flee from the merciless assault of the Assad regime—and the international community did not see this as an emergency. But now when refugees are once again at the gates of Europe, European governments start calling emergency meetings.

MS: In the event Assad brings Idlib under his control again—what is the situation like in areas the regime has already retaken?

LS: Idlib is the last province in the hands of the opposition, and that’s why it’s the target of ruthless assault by the regime. As for how bad it is in areas that Assad has gotten more and more under his control—look at the Ghouta or Dera’a. There are mass arrests. Anyone in any way affiliated with the opposition gets forcibly conscripted into Assad’s army, and these young men are then sent to the frontline in Idlib to die. It is a tragedy. Furthermore, humanitarian organizations withdraw from these areas as soon as the regime takes over. People would rather flee than live under the regime again.

MS: For the people in Syria it’s a matter of survival. Do you see any better prospects for people in this catastrophe?

LS: In Idlib, it is a luxury to have so much as a tent. People are sleeping outside in the cold. But that doesn’t mean that the resistance in Syria has dissolved. In Dera’a the people are still defending themselves—just last week there were mass demonstrations there. They are protesting against forced conscription, and are still demanding the fall of the regime. Even in areas where support for Assad is stronger, there are protests right now because of the desperate economic situation. So the situation is anything but stable.

I’m not very hopeful about the future; I don’t see any easy solutions. One thing is for sure, though: if people have the chance to self-organize, they do. After all the lives lost, the lost future, all the destruction, they won’t just suddenly say, “Okay, now we accept the regime.”

MS: Are there other protests that we don’t hear about?

LS: In Idlib there are also protests against extremist religious groups. Many Western journalists say that Idlib is an “al-Qaeda stronghold.” It is true that the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham is the dominant military force there. But this is a few thousand fighters out of three million civilians, and large parts of the population are decidedly against the presence of this militia. There are protests nearly every week—and this has been going on for months, indeed years. The people don’t want to replace one authoritarianism with another. They are struggling against the Assad regime as well as against the Islamists. The Western media generally overlooks this.

MS: Here in Switzerland, Assad is often seen as the “lesser evil” compared to jihadist militias like the Islamic State. In your book Burning Country, you criticize this framing.

LS: In the West, the choice in Syria is often framed as one between Assad and al-Qaeda. But this is a narrative that the regime intentionally established. When Assad was confronted with a revolution in 2011, he knew that he would not get any Western support if he crushed a peaceful pro-democracy movement. So he started labeling the movement as a “terrorist threat,” using War on Terror language, and calling the demonstrators Islamists. In addition, the regime purposely aided in strengthening Islamic extremism.

MS: How so?

LS: Thousands of peaceful pro-democracy demonstrators were brutally tortured in prison; at the same time a large number of Islamists were released—people who had been sitting in prison because they had fought against the US occupation in Iraq after the 2003 invasion. Now these people were useful to the regime again. It was a cynical trick by the regime: use religious extremists to Islamicize the conflict, and then present the conflict as a war against terrorism instead of a war against democracy.

MS: During the Arab Spring, people took to the streets demanding freedom, democracy, and social justice. What do you see as the turning point that led Syria to war?

LS: The revolution of 2011 faced massive repression by the regime. It wasn’t just shooting at peaceful activists and demonstrators; there were also mass arrests and mass rapes by Assad forces—they would go into opposition areas and rape the women. As a response, people tried to protect themselves, their families, and their communities from these attacks. They took up arms and formed local self-defense brigades.

MS: At the end of 2013, the dominance of Islamist militias increased dramatically. How did that happen?

LS: The moment in time is important. After the gas attack in the Ghouta in August, the opposition realized that the West would not support them—that attack had crossed the so-called “red line” that US president Barack Obama had set. I think when he backed away from this, people started joining up with Islamist militias to at least secure financing from Gulf donors. When Western states later stepped in with their “anti-ISIS coalition,” it was directed not against the regime, but was just another intervention in the so-called War on Terror.

In the Syrian conflict, however, it’s not just the military battles that are important. In 2012 and 2013, large swathes of Syria were liberated from the regime. During this time, local councils were founded; civil society blossomed; activists started countless independent media initiatives—this was the most positive time of the Syrian revolution.

MS: You are an anarchist. How did you perceive these events at the time?

LS: When the revolution began, I was very inspired by the wide variety of anti-authoritarian voices that suddenly stepped into the foreground. In the whole region, in countries like Tunisia and Egypt, groups were founded, campaigns emerged. Especially in the liberated areas of Syria, people started to self-organize and put into practice what I would call anarchist ideals—not necessarily out of a consciously anarchist perspective, but out of the need to maintain a functioning society. I think anarchists and anti-authoritarians in the West missed a chance to really look at and learn from the experiences of these people.

MS: What values and ideas drove the Syrian revolution?

LS: When I talk with other Syrians about what the revolution meant to them, or what was most important to them about it, many talk about overcoming the fear that had been such a barrier before. But then it is mostly about the experience of collective organization, of solidarity, of mutual aid that was put into practice. Whether it was sending aid to communities that were under military attack, or founding local councils and forums in order to maintain civil life and infrastructure—people had lived their entire lives under the authoritarian control of the state, and suddenly they could breathe. Those were the good days. They lived and experienced freedom. It wasn’t just a slogan or a demand—the people actually put it into practice.

MS: In your book you write about how the Syrian revolution is often called an “abandoned” revolution: ignored, misunderstood, slandered. Did we in the West fail to see the lines of conflict correctly?

LS: The focus on religious extremism definitely overshadowed the larger struggle. The protesters who were not just struggling against the regime but also trying to build self-organized democratic structures as an alternative always made up the majority of the opposition to Assad. But I think there are other reason why people ignored what was happening in Syria, especially the Western left: many only wanted to see the Syrian war as a geopolitical conflict, a proxy war among states, instead of seeing the social conflict, the struggle of the Syrian people against their state—and later against other states that intervened in the conflict.

MS: Why do you call out the left in particular?

LS: Ever since the Iraq war there has been a tendency on the left to view everything though the lens of an anti-imperialism directed solely against the US. But in Syria the US was not the primary actor driving the conflict. I’m not saying that they didn’t play a significant role at all—they did! But the imperialism that the Syrian people were struggling against was coming from Russia and Iran. Without their support the regime would have collapsed.

MS: That’s different in the case of Rojava, the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Syria, where the Western left has shown significant support. Where does this selective solidarity come from?

LS: There’s a whole range of reasons for this. Many Kurdish activists have lived many years or even many decades in the diaspora, so they already had an existing solidarity network to fall back on when the conflict in Syria broke out. Syrians in other parts of the country didn’t have these connections yet. Another reason has to do with a certain kind of racism, orientalism, Islamophobia—a vague feeling that Sunni Arabs just aren’t “ready for democracy.” This is also the reason the Western left was so willing to accept the discourse calling everyone jihadists and terrorists.

MS: What could real solidarity have looked like beyond just futile gestures of sympathy?

LS: People should have shown their solidarity with civil society and the grassroots and women’s rights movements, the democratic structures that were being built in liberated areas, the humanitarian organizations that were trying to support the displaced, and the campaigns for the imprisoned and disappeared. It is well known how horrific the conditions in regime prisons are. There were clear calls for solidarity from civil society. Whether in Syria or in the diaspora, I think a big part of the problem is that Syrian voices are just not listened to. They know best what’s happening in their country. We could learn from their experience and support them.

MS: Syrians are now speaking out under the hashtag #CantForget, about torture and war and the traumas that will stay with them forever…

LS: That is the other side of what I was saying before about the gains people managed to make out of the revolutionary process. Of course there have been incredibly negative effects as well. Many are immensely traumatized by the extent of the suffering that they, their families, their friends, and their communities have endured. Millions of people have been displaced. An entire generation of Syrian children has grown up in refugee camps, without access to education. A large portion of the population lives in absolute desperation and has no hope. This kind of despair does two things: it creates extremism, and it creates a thirst for vengeance. This can potentially lead to enormous problems.

MS: Do you see a way out of this situation?

LS: In Europe, the reaction is primarily to build up the security apparatus. But more border guards and Frontex officers is certainly not the right answer. To confront extremism and despair, you have to give people hope and a future. On the one hand that means looking for an appropriate solution to the conflict within Syria, so that people can go back home without fear of repression. On the other hand this also means that European countries need to find a solution for themselves, in which they offer the people who are in Europe adequate health, education, and work opportunities.

MS: You’ve been working on issues of war, torture, and repression for twenty years. How do you keep yourself from breaking down in grief and resignation?

LS: I believe everyone who deals with these issues has experienced periods of darkness, despair, and depression. What keeps me going are the people in Syria who in spite of everything haven’t given up. I live in a safe place, and I have a feeling of responsibility for everyone who isn’t as lucky as I am.

MS: The last sentence in your book reads: “As long as Assad stays in power, the revolution will continue.” The book came out in 2016. Would you still say the same thing today?

LS: Syrians were not only abandoned by governments—which I have personally never placed much hope in—but really by people. Like I say, I would have expected solidarity, especially from the left and grassroots movements. The situation seems so bitter and hopeless today; the people are so exhausted and traumatized. But then I see for example the protests in Dera’a. Or I go to talks by young Syrian activists who now live in the diaspora and might have been children still when the revolution started. They are looking for ways to organize and do something. This energy inspires me.

MS: For the future?

LS: The 2011 revolution changed something. Not just in Syria, but in the whole region. A shift in consciousness took place, a whole range of new experiences and ideas emerged—this can no longer be defeated. With arrests and killings, you can maybe reconquer a territory and defeat the organized opposition on the ground. But the ideas live on—and they will continue to shake Syria, the region, and the world.

The British-Syrian activist and author Leila al-Shami (41) lives in Scotland, and with Robin Yassin-Kassab published the 2016 book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War. She has been engaged with human rights and social movements in the Middle East for around twenty years, and co-founded the Tahrir-ICN network. Her father was a political prisoner under the regime of Hafez al-Assad, the father of the present ruler. To protect her family in Syria she prefers not to appear in photographs.

If you would like to show solidarity, Leila al-Shami recommends supporting humanitarian organizations that are active in Idlib: the Molham Volunteering Team, the Violet Organization, or the White Helmets. The women-led campaign Families for Freedom, meanwhile, works for the release of imprisoned relatives in Syria.

Leila al-Shami reports on developments in Syria at her blog.

Fragile Ceasefire

Last Thursday, Russia and Turkey negotiated a ceasefire in the disputed Syrian province of Idlib. But the agreement is not holding: on Monday the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported renewed hostilities between the Syrian regime and opposition militias. A “tense calm” reigns in the region.

The struggle for for power in Syria continues. With the Sochi agreement in 2018, both Russia and Turkey had wanted to establish a “deescalation zone” in Idlib. But the new deal leaves many things open: how the future safety of those displaced will be ensured, for example. This is around one million people.

Syria: A Chronology

2011

In February and March 2011, Syria sees its first demonstrations in the southern border town of Dera’a.

In mid-March, security forces meet the protests with violence. Local militias begin to form under the banner of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), which will become the largest opposition force by September.

2012

In September 2012, Iran admits that members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps are supporting Assad government forces.

2013

In April 2013 come the first reports of the Assad regime using chemical weapons against the population. Later a UN investigation will confirm gas attacks by the regime in the Ghouta region outside Damascus.

Starting in December 2013, Islamist militants increasingly begin to dominate the military opposition—among them the so-called Islamic State (IS).

2014

In September 2014, the “anti-ISIS coalition” starts up airstrikes against the so-called Islamic State in Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor. This military alliance includes the US, Australia, France, and Great Britain.

2015

After Iran, Russia also intervenes on the side of the regime in September 2015, once again preventing the defeat of Assad’s forces.

2016

In March 2016, the Kurdish project of self-government in northern Syria, Rojava, is officially announced. The Turkish government fears the emergence of a Kurdish state.

Regime forces declare the retaking of Aleppo in an “important turning point” in December 2016. Tens of thousands of civilians flee. The city lies in ruins after years of airstrikes and shelling.

2017

In November 2017, the governments of Iraq and Syria declare the Islamic State militarily defeated.

2018

At the end of January 2018, Turkey attacks the northern Syrian province of Afrin. This is the beginning of Turkish military strikes on Kurdish autonomous areas, which will resume in fall 2019.

2020

In February 2020, Turkey begins military action against the Syrian army. Refugees fill the camps in Idlib province.

Translated by Antidote

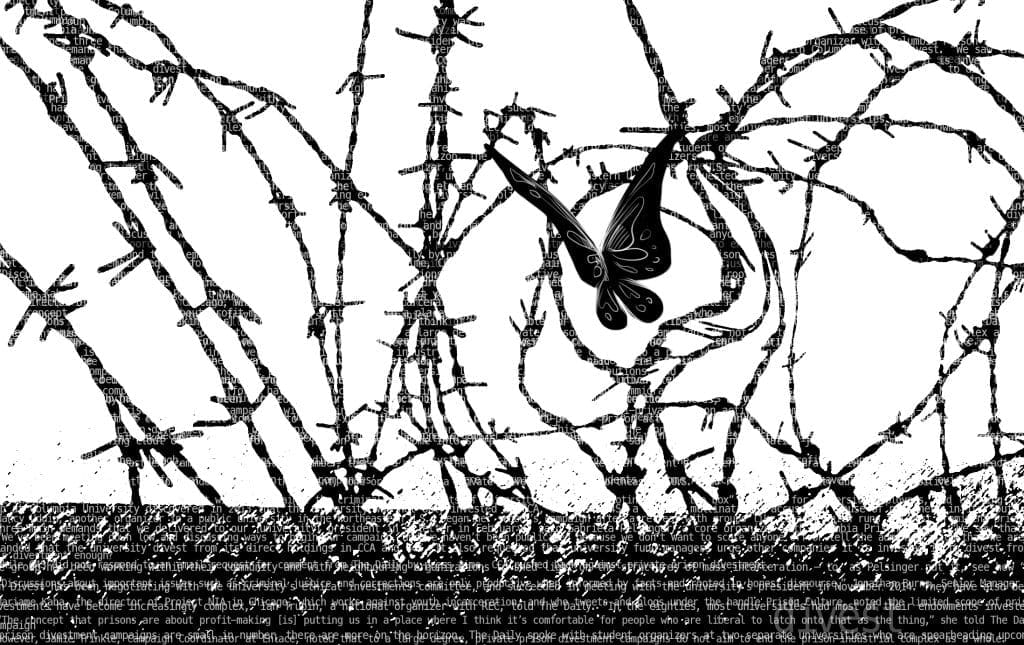

Featured image: collage by Tammam Azzam. Source: Syrilution Creative Arts (Facebook)