Transcribed from the 28 April 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

When people announced the territorial end of ISIS last year, all the states that were members of the coalition thanked themselves, thanked NATO, thanked each other. But we know it was the people of a revolutionary movement who were among the first to die: thousands of people—eleven thousand people, Kurds and Arabs, mainly. They fought together shoulder to shoulder, and they had revolutionary slogans. They had antifascist slogans.

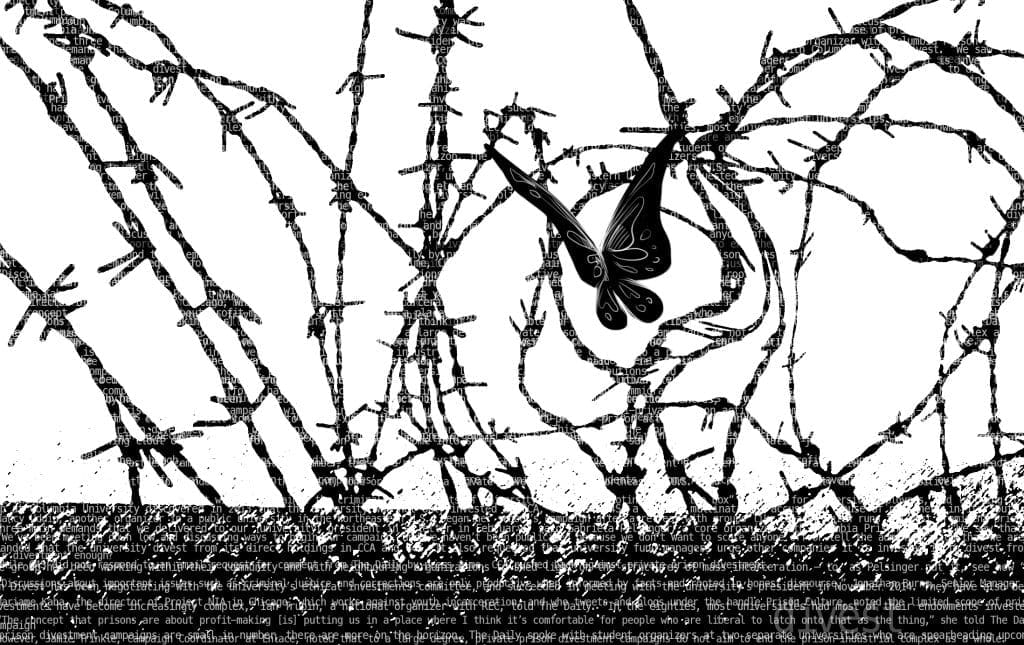

Chuck Mertz: Authoritarians want you to believe that there is no alternative, that any thought of anything other than the abusive system of violence and war that we currently suffer under is nothing but magical thinking, utopian fantasies and dreams that should be ignored and dismissed.

Returning to This is Hell! to remind us there is an alternative, political sociologist Dilar Dirik is an activist of the Kurdish women’s movement in Europe, and a contributor to the book we featured on last week’s show, Deciding for Ourselves: The Promise of Direct Democracy, which we discussed with the editor of the collection as well as one of its contributing writers, Cindy Milstein. Dilar’s essay in Cindy’s collection is entitled “Only with you, this broom will fly: Rojava, Magic, and Sweeping Away the State Inside of Us.”

Dilar was last on our show in 2015. Welcome back to This is Hell!, Dilar.

Dilar Dirik: Hi, thank you. I’m so happy to be back.

CM: It’s great to have you on the show again.

You write, “A year into the war in Syria, on July 19, 2012, the people in the majority-Kurdish north of the country took over governmental facilities, hoisted their yellow, green, and red flags, and chanting aloud revolutionary music, declared revolution in Rojava. Not many years have passed, but enough things have happened since then to fill entire libraries.”

Why then? What happened at that moment to allow for that to occur?

DD: There was a combination of a lot of different factors. Of course we cannot separate what happened in Rojava at the time from the larger situation in the region—one must place it within several different histories. On one hand, there is the decades-old history of the Kurdish freedom movement, and its legacy in Rojava specifically. But there are also other democratic quests in the region more generally: this was at the time of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011. Across different countries in the region, people started to protest on a larger scale against authoritarianism and violence from the states that they live under. Rojava must also be placed within the context of the war in Syria, which started in 2011.

But it cannot only be reduced to a moment that started in 2011, because the Kurdish freedom movement had been operating in Rojava secretly for much longer than that. That’s why, when things started to develop in Syria, a year into the war, people took the necessary steps to protect their own regions from entering the spiral of violence that was taking place at the time.

There’s also an autonomous women’s history that needs to be considered. There’s a combination of different histories that led to what was declared as the Rojava revolution.

CM: You also point out that “a monstrous fascist entity, the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), rose up, conquered vast territories, and fell within years. Yet ISIS only accounts for a small percentage of the unimaginable violence, brutality, and trauma inflicted on millions of people by the Syrian forces and other groups involved in the ongoing war, not least of which involves the global arms trade that sponsors and perpetuates conflicts around the world.”

Here in the States, within our media, the Syrian war was essentially “the war with ISIS.” President Trump’s announcement of the fall of ISIS was sold to us as a victory by the United States in the Syrian war. What do we miss in understanding the Syrian war when we only see it as a war with ISIS, and Trump claims the fall of ISIS is a US victory in the Syrian war?

DD: There’s a lot to be unpacked there. The US has played a very negative role throughout, since 2011. The United States under the Obama administration had also actively contributed—through cooperation with countries like Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia—to the rise of jihadist groups in the region. This is not a secret. I think I even mentioned this back in 2015 on your show as well. Even Joe Biden at the time admitted this: he said something along the lines of ‘our partners in the region contributed to the rise of extremism, including ISIS.’

We cannot separate the rise of ISIS from the violence that was generally taking place in the region. People speak of course of the violence of the Syrian regime. The situation was very violent quite early on, and there were extremist groups involved—al-Nusra and ISIS—and there still are today. It’s whitewashing to reduce the whole situation in Syria to a US-led victory against ISIS. Consider this darker story that people prefer to cover up: ISIS existed and had been committing massacres in the region for much longer than when the US decided to intervene, which was in 2014.

When I was last on your show it was still the early months of 2015, when the siege of Kobanê was broken. Kobanê was the first city that defeated ISIS. How did that happen? The involvement of the US-led coalition started in 2014, in September-October, because of the resistance of Kobanê. The people in Kobanê, and in Rojava more generally, had been resisting these forces: not just ISIS but also al-Nusra and other al-Qaeda linked forces that had been openly operating in that region. Also—one must say this very explicitly—Turkey played a role in the context of the war in the north.

People had been exposed to these jihadist groups very early on, and they had been establishing their self-defense forces as early as 2011, and then openly since 2012 (we all know the People’s Protection Units and the Women’s Protection Units, the YPG and YPJ). I’ve interviewed many people who gave testimony on these events. Quite early on, there were not just the YPG and YPJ; the people on the ground were also receiving arms training—openly. There was a mothers’ battalion that was formed in June, of elderly women who said, ‘We will be prepared when ISIS attacks our region, because we have seen what ISIS has done to women in other parts of Syria and Iraq.’

Of course, people remember very vividly what happened to Yezidi women in Şingal (or Sinjar) in August 2014, when thousands of women were abducted and sold into sex slavery; thousands of men were murdered on the spot. The Yezidi massacre was acknowledged then as a genocide. When all of these things happened, nobody in the world was doing anything. People were watching. It was people on the ground, led by the Kurdish freedom movement, who were resisting.

People did not want a repetition of such massacres. So in Kobanê, people were prepared. They were taking their precautions, and they did not have anybody to rely on. This was long before US involvement. I’m stressing these events just to make sure people understand that the US got involved much later, and it was really people on the ground who had no backing, no funding, no arms—they had a few Kalashnikovs and the weapons they were able to take from ISIS and other groups they were fighting.

And they organized themselves with a political ideology. It should not be understood as just a random, spontaneous resistance. It’s the product of decades of political organizing by the Kurdish freedom movement along revolutionary ideas that gave people the necessary political consciousness to be prepared to fight. There’s nothing spontaneous about it in that sense. It was a popular mobilization.

Then, of course, people were watching the siege of Kobanê. I interviewed women commanders of Kobanê. Meryem Kobanê for example was there during the whole siege. She mentioned how they had been fighting for thirty days or so, and only then, as the international media outlets were across the border in Suruç, on the Turkish side, nobody could deny that there was an incredible resistance going on in Kobanê.

This is when the Obama administration decided to get involved. This was really uncomfortable for the people resisting on the ground, for other reasons—but in that moment everybody appreciated these airstrikes, because people were about to die. There was going to be another massacre before the eyes of the world.

Rojava in that moment was an alternative in a region that had historically been forced to choose between different kinds of dictatorships or different kinds of reactionaries, whether “secular” militarist regimes or Islamist regimes, all of these different groups. This discourse has been actively imposed on the region.

For the US, of course, this meant engaging in a tactical alliance with the enemies of Turkey—and Turkey is an important NATO ally of the US. So this was all very complicated. Eventually this cooperation was taken further, and with the foundation of the Syrian Democratic Forces there was more direct and explicit cooperation. Throughout this time, the Turkish state was expressing their discontent, criticizing the US for “supporting terrorists”—because for the Turkish state, it was always clear that they were happier with ISIS at their border than with a Kurdish-led autonomous project. The Turkish discourse has been to say the PYD, YPG, and ISIS are all the same: they are all terrorist elements, and we need to eliminate this threat to our national security. The US, on the other hand, was saying the SDF are different from the PKK.

On an ideological level, this led to an attempt by the US to try, discursively or directly, to dissociate the revolution in Rojava from its revolutionary roots, by saying, “This is our victory.” When people were announcing the territorial end of ISIS last year, all the states that were members of the coalition thanked themselves, thanked NATO, thanked each other—but we know it was the people of a revolutionary movement who were among the first ones to die: thousands of people—eleven thousand people, Kurds and Arabs, mainly. They fought together shoulder to shoulder, and they had revolutionary slogans. They had antifascist slogans. In order to deny the revolutionary character of something like this, one must change the discourse. One must use all of the media arsenal that they have available to undermine that it was a socialist project that led the fight against ISIS.

It’s important to protect these legacies, to claim them. For women it was important. When the YPJ declared victory in Raqqa, they did so in front of a big picture of Abdullah Öcalan. They always explained that this was only possible—that women rose up against Daesh in places like Kobanê and elsewhere—because of this revolutionary commitment, because of the belief that women can be free. They said this struggle against ISIS that they led (and in which they liberated thousands of women, by the way, who had been enslaved by ISIS) is their gift to struggling women around the world. This was women’s history being written.

But if you look at the accounts of the corporate media, of the US official statements, it will look like another NATO victory. It’s very important for progressive people, for leftists around the world, to understand exactly what happened.

CM: Why is Turkey happier with ISIS being on their border than movements like the Rojava revolution?

DD: There are a lot of historic, ideological, geopolitical, and economic reasons for that. But in essence, if you look at the nature of the current Turkish government, it’s a very patriarchal, conservative, and frankly Islamist government, which has—with the help of the US and other groups, and the EU as well—been able to portray itself as a moderate government, a good progressive neoliberal partner in the region. Of course, it’s also the second-largest NATO army.

Turkey is a very conservative authoritarian country that gets away with all kinds of human rights abuses and war crimes at the moment, because people fail to understand just exactly what this government is up to. This has to do with things like the arms trade. Many European governments—and the US as well—trade in arms with Turkey. Turkey is one of the most important arms importers for Western countries. They are now dealing with Russia as well. So that’s that. For these economies to run, the war needs to continue.

At the same time, people have systematically downplayed the Turkish state’s involvement in supporting jihadist groups in Syria (and also within Turkey). And we’ve seen an increasing crackdown on people who oppose the government and its policies—not just its policies in Syria and in Iraq, but also domestic policies. Now the most progressive people—thinkers, writers, activists, politicians—are in jail. There are thousands of political prisoners in Turkey at the moment who have been excluded from the Coronavirus amnesty. Lots of people were able to leave prison, and of course that’s a positive thing, but political prisoners can be sacrificed, apparently, in Turkey.

All of this is important in considering the nature of the Turkish state, ideologically. There’s also the wider project: Erdoğan’s Turkey is specifically targeting ethnic and religious minorities as well. That aspect is also important.

The political, social, cultural project in Rojava, regardless of the level at which it could be implemented, is a progressive one. It is one that was established by women. It was one that showed a third way is possible in Syria. We do not have to choose between the Syrian regime and an opposition that may have started in a very genuine democratic and progressive way but was very soon co-opted and supported by reactionary forces from outside. And of course it’s not just Rojava. There are other progressive, freedom-loving people and movements in the region. These voices are actively being silenced.

Some people who I’ve interviewed have said Rojava in that moment was an alternative in a region that had historically had to choose—been forced to choose—between different kinds of dictatorships or different kinds of reactionaries, whether it’s “secular” militarist regimes or Islamist regimes, all of these different groups. This discourse has been actively imposed on the region by the US and others, through interventionism and foreign wars and all kinds of stuff.

By making Erdoğan’s Turkey look like a good option for Middle Eastern people, they are actually condemning women, ethnic and religious minorities, differently-thinking people, and young people to something that cannot and should not be an alternative. Erdoğan’s is not a moderate government. That’s something that people in the Middle East and North Africa need to understand. We were protesting as early as 2012 and 2013 about jihadist groups in the region, and how they were either directly or indirectly linked to the Turkish state. This is still something that people are not putting enough attention to.

It doesn’t really make much sense to appeal to states. They all buy into this. Progressive-thinking people and political organizations need to understand exactly what is going on in Rojava and they need to understand the ways in which the Turkish state is contributing to violence in the region.

CM: You were just saying that alternative voices are actively being silenced. To you, what explains that silencing by the media, especially here in the United States? What explains, in your opinion, US media’s denialism of Turkey’s support for ISIS? What explains this active silencing by the media when it comes to the actions and the successes of the Rojava revolution?

DD: There are two things. On one hand, the alliance between Turkey and the US is very strategic—not just because of the arms trade, but Turkey is an important ally for the US in the region otherwise, economically and politically. This is one reason why Turkey gets away with all of this.

Turkey openly recruited, armed, trained, and funded all of these groups which they now call the “Syrian National Army,” which are occupying large parts of the border region in Rojava and in the north of Syria by the Turkish border. And if we look at what happened in Afrin in 2018 when the Turkish army invaded (and has been occupying Afrin ever since)—these people are jihadists. There is no difference between their methods and those employed by ISIS. The first thing they did was torture the bodies of dead Kurdish women fighters, insulting them in very misogynistic ways. They went after Kurdish women politicians. They destroyed everything that the women’s movement had been building.

And not just in Afrin. I’m talking about the later operation that started in October 2019 as well. Hevrin Khalaf, a Kurdish politician who was working for peace and friendship between peoples, was targeted and executed. She was assassinated by these forces.

It’s not just the way they look. It’s their slogans, their methods. The women I’ve interviewed ever since are all saying there is absolutely no difference between them and Daesh. And these are forces that are directly armed, trained, and funded by Turkey, which is an EU membership candidate and also the second-largest NATO army. These are NATO’s allies. NATO’s allies are jihadists who use the same methods as al-Qaeda and Daesh.

This is outrageous. These people are filming their own war crimes, filming their human rights abuses. They are abducting women. They are targeting the religious sites of Alawis and Yezidis in Afrin and other places. They are looting people’s homes. They have documented these things themselves. It’s not a little claim made by some random Kurdish people. These jihadists are filming their own war crimes, and yet people are looking away. There are human rights reports, and also a UN report that was issued, mentioning these things.

People are saying we need to motivate Turkey to stop these abuses in the areas that it occupies—but nobody fundamentally challenges the occupation itself. The slogan of the women’s movement for the international day against violence against women was “Occupation is Violence.” But because of the anti-terrorism paradigm, because of the whole security discourse, people think it is legitimate for Turkey to invade these regions if it serves its national security interests.

Why? This is the second point. Because Rojava is understood as being directly linked to the Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK. The pictures of Abdullah Öcalan, the ideology, and the political practice are used as a pretext by the Turkish state to say that it is the PKK operating there. But it comes down to how you want to frame and understand the whole situation. People would not have been able to resist in Kobanê and elsewhere—people say this very openly, including the commanders of Kobanê: this is a legacy of the Kurdish freedom movement, and also a legacy of the Kurdistan Workers Party that has been operating there since 1979, when Abdullah Öcalan crossed into Syria. The political organizing and education that had been happening there meant that for the first time, women were leaving their homes for political work.

You cannot deny this legacy. But at the same time, the PKK’s terror label basically equates the PKK—the movement that is behind many of the progressive things that people like about the Kurdish movement, including the autonomous women’s movement—and the whole project of Rojava with ISIS. This has been Turkey’s discourse the whole time. Turkey employs forces that are committing war crimes, assassinating female politicians, torturing the bodies of women—that’s not terrorists. But the revolutionary movement in Rojava is a terrorist one. It’s a War on Terror thing, which is why Turkey gets away with all of this. It can say it is about national security.

Which is why it doesn’t really make much sense to appeal to states. They all buy into this. Progressive-thinking people and political organizations need to understand exactly what is going on and they need to understand the ways in which the Turkish state is contributing to violence in the region. Maybe it’s not so relevant for you guys in the US, but the European Union has given Turkey millions of euros for the so-called refugee crisis which, actually, Turkey and all of these states helped create. 300,000 people were displaced from Afrin in 2018. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced in the latest Turkish operation, so-called Operation Peace Spring, in October 2019. Turkey is actively creating refugees and internally-displaced people. Yet Turkey is receiving money from the EU, while it is using war criminals to attack these regions and turn more people into refugees.

It’s all a circle, a circle of war and violence. The European Union, the United States, and other countries are all implicated in it. Which is why we cannot separate what is happening in Rojava from wider things that are happening in the region, including the refugee crisis, the arms trade, and the rise of authoritarianism, racism, and people like Trump, Erdoğan, Bolsonaro, and all the others—they mutually reinforce each other. They have created a system in which people find it difficult even to imagine alternatives.

This is why there is such massive media silence, not just on the meaning of Rojava, not just about what has been built up there, but also the ways in which it has been attacked and is now being sacrificed for the sake of the economic and political interests of these forces.

We need to build power in a transnational way, in ways that we can find new vocabularies, where we can learn from each other, and understand that the suffocation of Rojava will also mean the suffocation of other liberation movements and struggles in other parts of the world.

CM: You write, “A decade ago, if you had told the impoverished and colonized Kurdish people in northern Syria that one day, internationalists from around the world would be buried in these lands after helping to defend the people’s resistance against fascism, who would have believed it?”

Some here in the States argue that we simply do not have the power to have a revolution, or any kind of political or social transformation. Yet with Rojava, the revolution is being made by those who are impoverished and colonized. So is our problem not the lack of power but the abundance of it? That is, is power—or even the illusion of power—an obstacle to revolution? Do we not rise up because we still believe, here in the States, that our vote has power? Do we need to lack power to get power?

DD: That’s a big philosophical question. I’m conscious of the fact that I’ve been talking about war and destruction too much, so let’s say a few positive things. It all comes down to political organizing. For the last couple of years here in the UK, or in the US and other places, people have been focusing so much on elections, on electoral campaigns, getting people on board to not re-elect Trump, Boris Johnson, and others. This kind of politics—which we can call electoral or mainstream politics, state-centric politics, whatever—is one side of the struggle. In Turkey, people are doing a lot of work on that level to change the government, to force it to accept some of the demands that people make. But that’s not enough. In order to be meaningfully politically powerful, we don’t have to adopt the same methods of power as those who are in power and who use that power to oppress people.

So how can we actually build power through alliance? We need internal political education, mechanisms for our own internal democracy. In the Kurdish freedom movement, the example I can give is the women’s movement, which is also a struggle against power within the movement itself, a struggle for anti-authoritarianism within the movement itself, through women’s autonomy. Likewise across the border. The Kurdish movement and many other movements are now reaching out to each other. We now say, in line with many other feminists in the world, that today the biggest social movement is the women’s movement. We’ve seen it in the 8 March celebrations in places like Mexico and Argentina, many different parts of the world. How can these struggles reach out to each other rather than being forced to ally with states?

The tragedy that happened in October 2019 happened also because of Trump’s announcement of withdrawing US troops from the region, which was basically a green light for Turkey to attack. Why did this happen? Why are Palestinians, for example, often put in a position in which they have to address their demands to other states that are also oppressive? Why are oppressed people, colonized people, always put in a position in which they have to accept whoever gives them help? It’s not going to lead us anywhere. It’s unfortunately the reality right now, but that’s also because the progressive democratic struggles in different countries are often too occupied with whatever is happening within the borders of their nation-state.

We need to build power in a transnational way, in ways that we can find new vocabularies, where we can learn from each other, and understand that the suffocation of Rojava will also mean the suffocation of other liberation movements and struggles in other parts of the world.

The criminalization of the Kurdish movement is also the criminalization of other social movements in Europe. The Kurdish movement is one of the biggest and most organized social movements in Europe, and the way it is targeted and harassed and criminalized is unbelievable. If people look into it more closely they will understand the implications of it. The attack on Rojava is really a campaign against all liberation movements. This is what we need to understand—and it is why it is important for us to defend and protect other liberation movements across the world.

That’s why I think seizing power means organizing from the grassroots, creating political consciousness among people, creating ways in which we can organize ourselves, methods of organizing that are not simply about how we elect a government that we like, but actually how we change the system. This is very important when we look at climate change and other issues as well. We are past the stage where we can say if we just change the government it will be fine. We literally need a bigger, more radical system change, and more and more people are understanding that. My hope and our hope as the Kurdish movement in general is that it will—it must—be led by the youth and the women.

CM: How much is the criminalization of revolution an obstacle to that revolution? And what does it say to you about the nation-state when transformation away from it is against the law, when discussion of transformation, even failed transformation, is a crime?

DD: The idea of the nation-state is totally opposed to social transformation, because the nation-state is itself a project of social engineering. As we see in the Middle East, where the nation-state is less than a hundred years old, it’s about one nation, one flag, sometimes one religion, one way of running things. The nation-state is holding monopoly over all different spheres of our lives—not just the economy, but also history, history-writing, meaning-giving. The media, society, culture. We are turned into subjects of states rather than understanding ourselves and each other in a more horizontal fashion as members of society.

We must shift away from just focusing on our government, our nation-state, our nation, our culture, whatever, and actually look in a more global way to understand the links between systems of violence and oppression and also the links between the struggles that we are raising. How can we strengthen each others’ hands? That must be at the heart of a new internationalism for the twenty-first century.

For us in the Kurdish region and movement, words like community and society are so important. How can we become societies again? How can we transcend this individualistic identity that is so tied to the state, where we’re all citizens of the state, our loyalty is to the state, the whole way in which we look at the world is so centered around what state you are a citizen of. How can we build communities, build societies?

As for criminalization: we see more and more, in different parts of the world, that social movements or political groups, political ideas are criminalized and equated with things like terrorism; radical women’s organizing or radical environmentalists’ organizing is equated with violent neo-Nazi terrorism or Islamist violence—reactionary fascist groups. We must ask ourselves, what does this mean? What is the implication of this? The nation-state basically takes over the right to say what is good and what is bad, to decide what is moral, to decide what is normal and what isn’t. By pushing people who are slightly challenging the state into the realm of criminalization, by criminalizing even the few alternatives that we have—that we cling to!—the state is trying to tell us no. If you do this, you are not normal. I will isolate you from society. I will put you in prison, or I will turn you into a paranoid person. I will surveil you.

All of these aspects are important to understand criminalization. Why do the same nation-states openly support or fund actual terrorists? We could reclaim the words terrorism and anti-terrorism from the state and make a very basic moral assessment of what terror is, and what terror actually means—why does the state get to decide what is terrorism and what isn’t? Of course there is some basic sense in which we can understand when something actually causes terror and violence and harm to people. But in other cases, it’s unjustified why certain things should be criminalized and not others. Why is the state able to get away with everything, and nobody will hold the state accountable, ever, for anything it does?

What do we mean by life? What do we mean by politics? What does it mean in times of Coronavirus? Criminalization is basically the suffocation of people’s ability to decide for themselves, as Cindy’s title suggests. So in this sense, social transformation must be understood in a different way. If we look at it from a feminist perspective, it’s also about the transformation of social relations. It’s about transforming our relations, our friendships, our families, our communities in ways that actually render us politically literate, render us more able to create the tools and methods for a self-determined and autonomous life. It doesn’t mean we can overthrow entire governments with it. But it is necessary to create communities in order for us to have a more collective, shared understanding of what is wrong in this world.

That is something that is really missing. Most people today may not even be aware of all the damage and harm that is being done to them. I think now, with the whole situation of the virus, people are opening their eyes to some of it. But actually, considering the fact that every day so many people are dying on the Mediterranean sea (again, we need to credit the European Union for these horrible crimes). People are dying, on a daily basis, on the way to a safer place. They are running away from weapons that were produced by European governments. I’m just giving this as an example to ask: How normalized is it for people around the world that all of this war and violence is happening? We get forced into thinking that actually this is just the world. People are just inherently bad. The world is just inherently bad. What can I do about it? I’ll just watch my TV shows.

But no. There are systems, there are structures that create and perpetuate these violences. And we can educate ourselves on them, we can understand them. But in order to really properly understand them we must shift away from just focusing on our government, our nation-state, our nation, our culture, whatever, and actually look in a more global way to understand the links between systems of violence and oppression and also the links between the struggles that we are raising. How can we strengthen each others’ hands? That must be at the heart of a new internationalism for the twenty-first century.

CM: You write, “The statist notions of socialism stand in contrast to movements and perspectives that rely on the consciousness as well as actions of everyday people and their potential to become subjects of transformative social processes without orders from above.”

Has socialism, whatever shortcomings it has had, not worked, not because “socialism doesn’t work,” but because the state doesn’t work? Is the biggest obstacle to socialism the state?

DD: I would say partly yes. The state, as a system, as a project, as an institution, especially the nation-state, especially the authoritarian states that we have today—states don’t have to look the way they do. But this is what they turn into, because the structures that they have, and the monopoly that they have on different aspects of life, make room for them to crack down on the liberties and rights that they are supposed to be protecting, in theory.

Socialism is an ideal. It’s not something that belongs to just one party, one individual, one legacy. In many different parts of the world, especially in the Global South, different movements, women, young people—people have died for this ideal. People have given all their lives for these ideals, because it’s a promise of justice. It’s a promise of liberation. Of course there are different discussions within it, but if we take it very broadly, and we divorce it from, say, the Soviet legacy or the Maoist legacy and so on—socialism is an ideal. So is anarchism, and other forms of freedom-focused, freedom-loving, justice-focused ideas and ideologies.

Of course the state then becomes an obstacle. If your concern is to seize power, to have a mechanism to control people, to control the economy, rather than turning people into agents of their own lives—if your concern is more about social control, about disciplining people (and that was one of the things about state socialism, the whole bureaucratic authoritarian apparatus that developed), of course at some point it will break with the promise of liberation. It will become oppressive itself.

If we look at socialism through feminist perspectives, through libertarian perspectives, through ecological perspectives—and also through non-Eurocentric or non-Western-centric perspectives—I think we can enrich our understanding. If we look at it in a very broad sense as a promise for liberation, socialism is something that we can all unite behind.

The future can only be built by people who actually have the imaginary, who have the willpower and have the desire—who have the love and passion and freedom in their hearts!—to believe that this is not how we need to be. We don’t need to live like this. We don’t need to destroy nature. We don’t need to resort to ecocide in order for economies to work.

Many people who have been taught to think of it as a dirty term—and I know this is the case in the US and other places—people don’t understand what it is. This is, again, part of the discourse, that people equate it immediately with the bad examples in history, with negative legacies—horrible legacies, actually. Not just “bad.” It’s really quite terrifying. But that’s not what socialism is. Socialism is what we make it. Socialism is something that we can build through building communities, through solidarity, through mutual aid, through finding alternatives to the state. In that sense, the claim “socialism or barbarism” is very much relevant to our times today.

To come back to Rojava, this was basically the idea that motivated the fighters and the people on the ground when they were resisting against ISIS. Not just the fighters; there was a huge mobilization on the popular level. It was literally socialism or barbarism—or fascism, in this sense. In a world in which especially women experience all forms of violence on a daily basis, of course women will become among the strongest if they politically organize, if they unite, if they find good methods to do that, if they don’t turn into elite movements but actually have roots in the culture, in the the popular masses, if they find approaches that are not authoritarian, that do not look down at people. This is very much possible—especially through people listening to feminists, actually. We will find ways in which we can reclaim words like socialism, words like anarchism, and the most beautiful aspects about them, which are basically about liberation.

CM: You write, “Yet this is a region where many taboos have been broken. Forcibly destroyed practices of self-sufficiency have now been remembered and revived, and people don’t just aspire to reinstitute the past, but rather to do better.”

To you, what explains why capitalism so often looks backward to the past for its future? Why does capitalism not simply try to do better than it ever has, instead of always looking backwards for solutions moving forward? Why does capitalism not have a magical future?

DD: Capitalism is killing the future. Capitalism is really not creative at all. Capitalism is often described as very innovative, very future-oriented, futuristic. But actually all the creativity of production comes from workers, from creative people, from artists, from those who are silenced and marginalized. Capitalism has no imaginary. It has no horizon. It just wants to get by and in the meantime make some people rich. Capitalism lacks the ability to imagine anything.

I’m talking as if it’s one agent—it’s not one Capitalism that sits somewhere in an office and makes decisions. But the whole structure, the infrastructure, the logic, the mentality that capitalism fosters always needs to look back and create myths about how things used to be, how we can go back to that. But who is the future? It is young people—who are suffering the most now from capitalist policies. It’s people who are able to think differently. People who are open-minded. People who say, actually this is enough and we don’t want this anymore.

America was never great. It’s a country that was based on genocide against Indigenous people. It’s based on the enslavement of Africans. It’s now based on the system of racism, of incarceration and violence. Sometimes I watch Trump and he says, “I don’t know, maybe it’s like this, or not, I don’t know!” But his words have massive consequences. Because of a phonecall with Erdoğan, the Turkish army was able to invade Rojava and displace hundreds of thousands of people, killing thousands of civilians. This is the future of capitalism. This is what they have in mind. They don’t care about life.

If a system like capitalism doesn’t care about life, then it can’t think about past, future, or present in any sense. It’s beyond time, because it’s just concerned with making profit in that moment. The future can only be built by people who actually have the imaginary, who have the willpower and have the desire—who have the love and passion and freedom in their hearts!—to believe that this is not how we need to be. We don’t need to live like this. We don’t need to destroy nature. We don’t need to resort to ecocide in order for economies to work.

This is why I think learning from Indigenous peoples, learning from communities like radical black communities in the US, feminists in different parts of the world, people in the Global South, revolutionaries in different parts of the world, these alternative projects that do exist—I think we need to look there to look at the future.

Sometimes some of the practices of certain communities are quite ancient, they are very old, so it may not make sense to look at them if you want to look at the future—but actually, what is the future? The whole concept that there is a linear progressive timeline, that we are advancing towards somewhere—that’s also a very Eurocentric and capitalistic mindset. How about we protect life? How about we sustain ourselves in ways that are not based on ideas around progress and technology and innovation? There are people who plan on colonizing Mars for rich people! That’s the mindset, the logic that we’re up against, when there is so much poverty, so much injustice in the world.

This is why we also need to rethink what we mean by future, by time, and start organizing in the here and now so we can even have a future, so that our planet doesn’t get destroyed. Listen to women! Listen to feminists. Listen to all of the people who are being targeted by the likes of Trump.

Can I just say one last thing? First of all, thank you so much. I’ve really enjoyed the conversation. There’s a lot of very horrible stuff—war, displacement. People really should pay attention to many of the other conflicts as well in the region, the Saudi-led war in Yemen, for example. Attacks happening in so many different places. But at the same time there are people who are doing amazing work. And people don’t need us to say “I stand with you,” “I am in solidarity with you,” or “Protect X,” “Protect Y.” We actually need to start organizing together. Especially now, with what’s happening in Rojava—we should not separate it from things that are also happening in Turkey, or in other parts of Syria, in Iraq, in the region in general.

I just wanted to say that on a positive note, because I felt that the whole thing was a bit negative. But actually, generally, there is hope. That’s one thing that people should never forget. There is hope and people can do things together if they organize.

CM: Dilar, thank you so much for being back on our show.

DD: Thank you so much. Have a wonderful day.

Pingback: Let’s Do Something Else Instead | aNtiDoTe Zine