Antinote: The following is an extended excerpt of a transcribed online presentation and Q&A with Andrea Chalupa on the topic of imperial war and genocide in the “bloodlands” of Ukraine, both historical and present-day, seen through the life and work of journalist Gareth Jones who defiantly exposed Stalin’s Holodomor.

Content warning for discussions of mass death and violence, including sexual violence.

Edited by Antidote for space and readability, published with kind permission of the event hosts. Watch the full conversation:

Feeling young and overwhelmed and very lost in the world myself, trying to find direction, I looked up to Gareth. I saw him as a historical mentor.

Discussion of the Film Mr. Jones

A conversation with Andrea Chalupa hosted by Minnesota Alliance of Peacemakers (MAP)

25 April 2023

Minnesota Alliance of Peacemakers (MAP) is a coalition of peace, justice, and environmental groups that has been active in Minnesota for thirty years as an important venue for activists to network and exchange ideas.

Carl Mirra: I have the great privilege and honor of introducing Andrea Chalupa, journalist and author of Orwell and the Refugees: The Untold Story of Animal Farm. She has written for Time magazine, The Atlantic, Daily Beast, and Forbes. She has spoken or lectured at Columbia University, McGill University in Canada, and has spoken before the National Press Club in Washington, DC. She is the founder of DigitalMaidan, an online movement that made the Ukrainian popular uprising the number one trending topic on Twitter at a time when, as Andrea put it, the media was obsessed with Justin Bieber’s arrest—a very important endeavor, as Maidan is often misrepresented.

She is the author and screenwriter of the acclaimed film Mr. Jones. I’ll turn it over to Andrea; I’m really looking forward to the insights she’s going to offer us tonight. Thank you.

Andrea Chalupa: Thank you to everyone for being here, it’s such an honor. Thank you all for your work for human rights, for the truth, wherever you are.

I am Ukrainian-American; I was born and raised in northern California, in Davis. My mom and dad were both Ukrainian. They were born in refugee camps right at the end of World War Two. My father’s family is from western Ukraine, outside Lviv, and my mother’s family is from Donbas, eastern Ukraine, which is—if you’ve been following the invasion, the genocide—where Putin first invaded Ukraine back in 2014. He seized Crimea and then he went to Donbas. I still have family on the front lines who refuse to leave, who are right in the zone of the shelling. They see it as their duty to stay. And also—where do you go as a refugee? You have to pick up your whole life. But they also choose to stay and let the Ukrainian soldiers come, take showers, charge up their phones, get whatever they need.

This war is very real to me. Just to illustrate: my father is in perfect health, he loves to walk, he loves to play tennis; he got a knee replacement and he was out and about two weeks later—he’s very healthy. When this total genocide broke out a year ago, his health went into sudden decline. It was just a shock to the system that something like this could be happening. These World War Two-type stories that we’re seeing in the news—it’s the stuff that I grew up with, that my grandparents experienced trying to get the hell out of the Soviet Union way back in the day. There are stories: there were four trucks headed down the road, and three exploded, and we happened to be in the one that survived. Those are stories that are happening right now, as we speak. To see these dark chapters of history repeating is very hard on the soul, very hard on the psyche. The amount you need to stay engaged with this, emotionally, is very difficult.

So I commend the peace activists who are standing firm, who are engaging in events like this, who refuse to look away, who see how important it is to bear witness. Because that is what the young, ambitious, idealistic Welsh journalist Gareth Jones did: he risked his life and career to bear witness. I focused on him to tell the little-known story of the Holodomor, Stalin’s genocide famine in Ukraine, because growing up in northern California, my grandfather was the world to me. He would take me to get donuts on Sunday. I would sing songs for him from The Little Mermaid at the top of my lungs, and he thought it was fantastic. It wasn’t until I was older that I had heard and started to understand the stories of what he survived growing up in Donbas, and how it transformed with the Russian revolution and the Communists coming in, and Stalin of course—and, as a young man, surviving the famine himself.

Shortly before he passed away, my grandfather wrote down his life story on a Ukrainian typewriter and gave those pages to me. Then I went to college. I studied Soviet history at UC Davis, spent a summer at the Harvard Ukrainian research institute (which is putting out fabulous work right now from eyewitness accounts of the current genocide), and then I traveled alone: I had saved up some money working in college, and I went with my grandfather’s memoir typed in Ukrainian and lived in Ukraine. I had it translated into English, and that’s when I began in earnest trying to write this screenplay. I was in an internet cafe in Kyiv when I came across Gareth Jones’s family putting out information about him. Right away—it was a lightning bolt moment—I realized this is my hero. This is who I’m going to try to tell this larger story through. This young man is so brave, so strong. And feeling young and overwhelmed and very lost in the world myself, trying to find direction, I looked up to Gareth. I saw him as a historical mentor, someone I could cling to in a world that was changing rapidly, with Facebook and social media taking hold.

Gareth was basically my anchor in my twenties. I’m so grateful that I had that, and I recommend a historical mentor to everyone out there, because they make a big difference. I clung onto Gareth: I got to know his family, I got to know all sorts of historians, and I interviewed survivors of this famine who would share their stories with me. I talked to a lot of children of survivors who shared a very common story: even though these were families that had emigrated to the safety of America or Canada, they were still afraid to talk about what the famine was like. They carried that terror with them.

It’s very important to understand that this was an engineered genocide. Raphael Lemkin, the human rights lawyer who developed the Geneva Convention Against Genocide, who coined the very word genocide, held up the Holodomor, Stalin’s genocide famine in Ukraine, as a classic example of Soviet genocide. The man who invented the concept and word of genocide himself held up the Holodomor as the classic example.

There are great books on what the Soviets did. We had a team of historians, including Timothy Snyder at Yale University who wrote Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin about how those two madmen influenced each other. That book opens with the story of Gareth Jones, because that’s how much his story captured the hell of the 1930s, the rise of fascism, the rise of Communism, and how these two monsters worked together, met each other, and ultimately clashed over what became the bloodlands: Ukraine, Belarus—millions killed in genocides, the Holocaust, World War Two, and so on.

What brought all of us together was that truth is powerful; truth matters.

Timothy Snyder was one of many historians on this project. We had historians on the ground in Ukraine, we had historians at the universities of Alberta and Toronto; we had a lot of experts read the screenplay to give it life and authenticity. On top of that, our director, the three-time Academy Award nominated filmmaker Agnieszka Holland, is known for doing a lot of powerful hard-hitting films like Europa Europa, the story of a Jewish boy who hides in the Hitler Youth to survive. She also directed the original version of The Secret Garden; she’s done a lot of television like House of Cards, The Wire, The Affair, Rosemary’s Baby, and so on. This story was deeply personal to Agnieszka Holland too. Her parents were both journalists. She grew up in Soviet-occupied Poland, and her father’s official cause of death was suicide while under police interrogation. He jumped out the window. When that news was announced in the newspaper when she was a little girl, she went mute. If you know Agnieszka Holland—for her to go mute is a very big deal. So this movie was incredibly personal to her, and she had a lot to say with this film.

This film was made by a coalition of soulmates who came together. It was a very difficult film to make—it’s a film about a little-known genocide. It’s not a Marvel movie. We were filming in a heavy snowstorm in Ukraine on the ground. We had crew members in Ukraine crying on set because they recognized their own family stories in what we were filming. We had villagers coming out of their homes to watch what we were doing: old ladies who had their own stories, because they remembered living through the famine as children. So it was very heavy.

And god bless the actors, James Norton and Vanessa Kirby and Peter Sarsgaard: these are extraordinarily in-demand actors who get offered a lot of incredible roles. Vanessa Kirby was in Mission Impossible with Tom Cruise. James Norton is a huge star in the UK—he could likely be the next James Bond. Peter Sarsgaard is in the recent Batman movie. These are actors who can do anything, and they chose to move heaven and Earth to join us on set in Ukraine and Poland to recreate this world.

What brought all of us together was that truth is powerful; truth matters. There are archives that have opened up since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and there are memoirs, survivor testimonies, incredible research that is coming out on this genocide. Part of the crime of what the Soviets did in 1933 by deliberately starving Ukraine is that to this day, most people have never even heard of it. They were so successful in covering it up then. The machinery of that is very similar to what is going on today, the both-sidesing of Russia’s current genocide in Ukraine, trying to dismiss it all as a proxy war, when Russia has agency and Ukraine has agency, and Ukraine is fighting back for survival.

I want to play an overview of the film featuring our actors:

Gareth Jones was a rising star: he was in his late twenties, he was foreign secretary to David Lloyd George, the World War One prime minister who was still influential in London. Gareth Jones spoke several languages fluently: Russian, German, French. He was energetic. He had a way of seeing between the lines. He was a humanitarian and anti-conformist. He waltzed right up and talked his way onto Hitler’s plane, the new chancellor of Germany, flew across Germany with Hitler, and wrote an article saying if this plane should crash, the whole history of Europe would be changed. And he was right. That was a big scoop for him, and he followed it up by going to Moscow to chase down rumors of a famine.

The real-life Gareth Jones had traveled to the Soviet Union three times total. He knew his way around. He was very close with his mother, who as a young governess had spent time in Donbas—in Donetsk, a city which was developed by a Welsh industrialist. The town was originally called Hughesovka after John Hughes, and she had been a governess for his children, teaching English and so on. Gareth grew up with her adventures of being on the edge of the Earth. He was drawn to Ukraine for that reason. Ukraine was personally important to him.

So Ukraine represented my grandfather, who was the world to me; Ukraine represented Gareth’s mother, who was the world to him. And that’s how our fates collided.

Gareth came up against a celebrity of his day whose name was Walter Duranty. He was nicknamed Our Man in Moscow. He was an eccentric character, very bohemian. He was into the occult, which I don’t judge—but he was a lover of Alastair Crowley, the Satanist. They would do these black magic orgies in 1920s Paris, and Duranty would even write Latin hymns for their orgies and they would ritualistically sodomize their lovers together—all this dark stuff, which is great research when you’re a college student like I was digging into all of this.

Duranty would hold court in Moscow. He threw the best parties, and all of the “illuminati” who were flocking to Moscow to see this great exciting experiment of Communism up close were making pilgrimage to Duranty. He was the credibility, he was the voice for the world, the window of what was going on over there. Right when he won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Stalin was when Stalin was laying the foundation for what would become the genocide of Ukraine. Stalin was sending his agents into Ukraine; they were deliberately confiscating the food. They eventually closed the borders of Ukraine so the starving refugees could not leave. People could not get out, aid could not get in. People were left to starve to death, confined in this prison.

When Gareth talked his way to the front door of the Moscow establishment, name-dropping Lloyd George, he convinced the Soviets to roll out the red carpet for him. He was a hustler, which I admire, and the Soviets sent him on a trip to Kharkiv, the capital of Soviet Ukraine. But Gareth, before reaching the city, hopped off the train and walked for many days from empty village to empty village, interviewing people on the verge of death. He was eventually picked up by the Soviet secret police, and again he hustled his way out of that situation.

The sight of him must have terrified those police; they quickly brought him to the nearest embassy and got him the hell out of the country. And as soon as he got out, he held a press conference and blew the lid off this thing: the famine became a very big news story. Back in Moscow, Walter Duranty and other illustrious foreign correspondents got together with the Soviet censor and made a deal to write articles saying that Gareth Jones was lying. They did this because if they didn’t, they would lose their visas. They would lose their access. They were practicing what is known as access journalism.

We’re going to be living with the fallout of this war for many generations to come. And we all need to be there for Ukraine, no matter what it takes. You don’t go through something like that and become okay. We shouldn’t expect anyone to be.

The Kremlin did something back then that it’s doing today: it took hostages. When rumors of the famine were getting out, when it was becoming harder and harder to contain Stalin’s genocide famine, the Kremlin arrested six British engineers who were in Russia helping the Soviets build and modernize Stalin’s empire. These six innocent men were interrogated, some would say tortured, and thrown into prison. This was a shocking event. This was like Brittany Griner being arrested. It’s like the Wall Street Journal reporter who was just arrested. It was a shocking situation where the Kremlin was taking hostages. They had that strategy back then to try to blackmail and pressure people into silence, and they have that strategy today.

Gareth Jones called it out; he was very tenacious in pushing his reporting. But he paid the price for it, because Lloyd George, his longtime friend and mentor, wanted nothing to do with him. Gareth had flown too close to the sun and he’d created problems between the British and the Soviets. At the same time, Walter Duranty was trying to broker a deal to get FDR and the United States to finally recognize the Soviet Union and bring everyone together so that Western industrialists could go to the Soviet Union and help Stalin rapidly modernize his empire and make a lot of blood money.

If you’re wondering why so many turned a blind eye, it’s why so many turn a blind eye today, too. It’s because they want to make money. It’s like the Koch brothers’ dark money political network. They’re funding inside-the-Beltway people, analysts and think tanks, to try and argue that we have to do business with Russia. The economy comes first, all the money we could make together comes first. It’s the same dynamics that you see going on today, which is why it’s so important for us to have a united front and to hold fast on sanctions, to push for even greater sanctions. Alexei Navalny, who is facing death in a Russian prison, and his team provided a list of six thousand Russian oligarchs who hold up the whole architecture of Russian corruption that should be sanctioned, along with their families. And instead we get all these reports of their families enjoying the good life at ski resorts in France and shopping in Paris and so on.

We really need to close those sanction loopholes, force corrupt Russians to stay in Russia and live in the country that their corruption and greed is destroying. That has to be a part of this.

I am going to pause here and let people chime in with questions.

CM: A friend of mine at the university studies historical trauma and how trauma can be passed on generationally. How do you think historical trauma or the traumatic experience of genocide might affect Ukrainians’ mindset today?

AC: It’s such an important issue. We have to mainstream that discussion for everyone. I think the movie Encanto, a children’s story about generational trauma, is groundbreaking. It set off a TikTok movement of kids sharing what their grandparents were like, what their mothers were like because of the generational trauma they’d experienced. That opened up the conversation. For the sake of all of us, and obviously for Ukraine: any country that’s been through a genocide needs a lot of support in this regard.

One of the things the Russians did back in World War Two that they’re also doing today is systemic rape. There’s one woman—she’s in her fifties and was raped by a soldier, in her home, who was her son’s age. She’s getting therapy for that. A lot of the aid that US taxpayers are giving to Ukraine is to pay for therapists to help the survivors of sexual violence, sexual trauma, rape—mass rape. There is the not-uncommon story of a five-year-old girl being raped in front of her father. Our tax dollars are going to support healing services and trauma services for these survivors and their families, so they can function, so they can feel any sense of security they can get back.

In terms of generational trauma, we’re going to be living with the fallout of this war for many generations to come. And we all need to be there for this country, no matter what it takes. You don’t go through something like that and become okay. We shouldn’t expect anyone to be. Even the trauma of the Soviet Union was something that would wreak havoc on modern democratic Ukraine.

If you want to give money to support Ukraine, there’s a wonderful organization that sprouted up with Euromaidan, the 2013-14 revolution. I know these guys personally; the group is called Razom, which means “come together.” Years ago, they hosted an event where they invited me to speak about this very topic, called “How Do You Break Out of the Soviet Mindset?” The trauma of the Soviet system of keep you head down, hide, the feeling of terror has lingered in Ukrainian society because of what was suffered under the Soviets.

That Soviet mindset created a lot of frustration in among Ukrainians even before the war: there was this idea emerging that you’re no longer under terror, you have agency, you have a voice and your voice matters, and that was a conversation they were having before the war, to get people to come out of their shells. Now that we have this genocide, it’s going to take teams of therapists, teams of doctors, teams of psychologists, teams of services to come in, village by village, city by city, and help people come out of their shell and feel safe, help them learn how to live and manage their trauma.

My grandfather, right before he passed away, wrote down his life story in vivid detail. The trauma that he experienced of Stalin stayed with him. All those years he was taking me to the park, pushing me on the swing, the trauma was there. So yeah, the conversation we all need to be mainstreaming is how to be gentle with that trauma, how to talk to that trauma. There’s a wonderful book that I think is worth reading for any of us, because we’re living in an age of mass trauma: The Body Keeps the Score. It’s about the tricks that trauma can play on you, the danger-mapping, the hyper-awareness, the hyper-vigilance.

I do wonder how much of my own ingrained thinking is the family trauma coming in. I do feel hyper-vigilant. I have my podcast, Gaslit Nation, where I’m constantly warning that the worst is going to happen (and unfortunately I’ve been proven correct). I wonder if that hypersensitivity comes from my own family history. All those years when I was researching my grandfather’s story and reading his memoir and what he survived and lived through, yes I was doing it because I yearned to be close with him again; I missed him and I wanted to be with him again, I wanted something real. But there was also this big question in my mind: what would I have done in that situation? What would I have done if I were him?

The children of the children who are facing this genocide in Ukraine are going to be living with that. They are going to be asking themselves those same questions.

CM: Someone in the chat is interrogating the word genocide, I’m sure you’re familiar with these arguments. I’m reading Stanislav Kulchytsky, a scholar who wrote on the Holodomor in Ukraine, and he uses the word ethnophobia. You already gave the powerful example of Lemkin; that doesn’t seem to convince people somehow. What do you say to those who say you shouldn’t be calling this a genocide?

Putin is a dictator who has engineered a propaganda empire for himself, and he’s fallen for his own propaganda.

AC: It’s genocide by all definitions of the word genocide. Any time you’re kidnapping thousands of children and taking them away from their home into a foreign country and brainwashing them, telling them that their parents are dead, their parents don’t love them, these are your new parents now, your new family, you’re going to learn Russian, you’re a Russian now—the mass kidnapping of children to reprogram them under another nationality, another political group, is the very definition of genocide.

Wagner is a mercenary group founded by an oligarch close to Putin, it’s propped up with Kremlin money. Wagner is active in Syria and in various parts of Africa, carrying out war crimes. Wagner is so-named after Hitler’s favorite composer. It is a far-right mercenary group, and a couple of their soldiers who were forced into this war (they were prisoners who were promised to be freed if they could survive six months in Ukraine, which they miraculously did) came out to give testimony to a human rights research group about what they did in Donbas. They were told by Wagner to go in and liquidate. Shoot all the people. Kill as many people as you can. Erase all the people.

As part of this, one soldier described how he went up to a five-year-old girl who was screaming, and shot her point-blank in the head. He shared that story. This is extermination.

Putin is losing the war. It was a really stupid miscalculation for him to do this. It shows you what a bunker he’s been living in. He’s surrounded by a bunch of yes-men. He’s a dictator who has engineered a propaganda empire for himself, and he’s fallen for his own propaganda. As a result there are something like two hundred thousand casualties, killed and injured. The best of Russia’s military, including generals, are gone—they’ve been killed. Russia has lost significantly more soldiers in one year of this invasion than they lost in all nine years of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It is a historic, monumental military failure.

The corruption that is plaguing this military up and down is not going away. All the stealing that they do because there’s zero faith in institutions and the system across Russia—it’s not going away. It’s only getting worse as people grab what they can in order to make whatever money they can, as all the supplies make their way down. They are getting Soviet tanks out of storage just to have some scrap metal out there, something they can throw in. They are pulling prisoners out of prisons across Russia. They are going for the poor, they are going for the ethnic republics across Russia—and they’re getting pushback against that.

There is no winning this war. China isn’t going to do it, because for all the criticism of China, China is pragmatic. So Russia is largely on its own, and there’s no turning this around. What do they have as a consolation prize? Genocide. Kill as much as they can, destroy as much as they can. It was genocide then under Stalin, and it’s genocide now.

In the years leading up to this total war, statues of Stalin were going up across Russia. Just recently a monument of Stalin went up mere feet away from an old monument to victims of his Great Terror. The oldest, largest, most prestigious Russian human rights group, founded by Soviet dissidents, called Memorial, for years was trying to bring names to the nameless, to give dignity back to those who were killed under Stalin and to fight for historical truth—their historians had their lives destroyed, were arrested by the Russian authorities, because they dared to unearth an unmarked mass grave from Stalin’s terror. One historian’s child was taken away from him, and he was accused of pedophilia simply because he dared to be a historian.

Memorial dared to show Mr. Jones in Moscow. The authorities shut it down, and liquidated the organization. Now Memorial is gone in Russia.

All those years when Putin was bringing back the cult of Stalin, he was getting all this ready. He was very clear in telling us what his intentions were. And when the Russians invaded Donbas, eastern Ukraine, all those years ago in 2014-15, what do you think they did? They put up billboards of Stalin. What is the motivation there? It’s empire. Russians today have such an imperialistic mindset; they’ve been fed it so constantly in their propaganda empire, they don’t know how to see themselves without it. That is very dangerous, because even if Putin’s gone we’re still left with that larger genocidal imperialist culture, and a lot of that seeps in going back generations, with Pushkin and others who have glorified the genocidal language of “squashing” the Poles.

The Soviet “Union” was a term of gaslighting. It wasn’t a union. These were captive states that were invaded by Kremlin forces, and the local populations were terrorized. The local languages were banned, and people were forced to speak Russian. Anyone who protested, the local intelligentsia in the Baltic states and Poland and so on, were forced to submit and faced prison and death. We’re dealing with an imperialist power. We’re dealing with the unfinished business of World War Two, because we used one monster, Stalin, to get rid of the other monster, Hitler. We always glorified Uncle Joe in the West—he was our great ally. Orwell had a heck of a time trying to get Animal Farm published because it was critical of Uncle Joe. The publisher who finally dared to put it out—his wife made him wait until the war was over so as not to upset the Soviets.

Right now what we’re dealing with is this unfinished business. We finally need to get rid of the Stalin monster.

CM: Here’s a more forward-looking question: can this historical trauma—memories of the Soviet Union’s atrocities in the 1930s and their repeat by Putin in today’s war—be connected in some way to the resilience of the Ukrainian people?

AC: Absolutely. When the Chernobyl disaster happened, that was a radicalizing point. The Chernobyl tragedy was a horrific, painful reminder of Moscow’s knee on the neck of Ukraine. Chernobyl was a Moscow project. Gorbachev and the authorities lied about how bad it was; a parade was allowed to go on. People died from the fallout of Chernobyl. It was a reminder of the corruption, the lies, the terror of Kremlin colonization of Ukraine.

After Chernobyl, there was a massive push for independence. When they had an independence referendum, Ukrainians—east, west, north, south—overwhelmingly voted for independence from Moscow. They won their independence at the ballot box, and they’ve been trying to build out of that Soviet swamp for decades since. It was very hard, it wasn’t without sacrifice. There were investigative journalists who were killed taking on corruption. They would give birth to a new generation of journalists who would also, among them, pay the price: there were car bombs, even a beheading. But they still kept going, kept building, kept confronting corruption, confronting abuse of power, risking their lives, running towards danger.

A lot of that is testimony to how Ukrainians see themselves and their whole history. We talk a lot about our “founding fathers” here in the United States. Ukraine’s sense of founding fathers and mothers goes back to the year 1000, the Kyiv Rus, when Moscow was a far-flung wilderness. Kyiv was bustling with a significant kingdom that had high literacy rates and good rights for women at the time. They would marry off princesses and princes to the great royal houses of Europe and were very influential in their day. They had monasteries and beautiful churches, and a dynamic culture that was a place to be during that time in world history.

It’s important for people to understand that Stalin committed several genocides. What we’re talking about tonight is just one of them.

Ukraine sees itself as ancient, and a lot of Ukraine’s bards, poets, men and women, have always paid tribute to that, this larger sense of destiny, this larger sense of freedom. There was a constitution proclaiming equality in the seventeenth century. This is what they pride themselves on: a national identity which is a longing for freedom. They see freedom as a religion. It’s a very bohemian place. There are a lot of big exciting cities across Ukraine that are all competing with each other, a lot of big university hubs, a lot of young people, very avant garde. I would go to parties in Kyiv back in 2005, and I had to stand on a stool and recite a poem as soon as I entered, they wouldn’t let me in otherwise. It’s very cool! It’s a very cool place to be. I urge everyone to put Ukraine on your bucket list—obviously when the war’s over.

If you went to Lviv in the west, with its romantic cobblestone streets—that city is so overrun with refugees and journalists that the plumbing infrastructure is stressed. But do put it on your bucket list to go to Ukraine. It’s got such a fascinating, ancient history and really prides itself on having incredibly deep roots. And they pride themselves on being intellectual. That’s why they’re blowing the West away on how quickly they’re learning on these Patriot missiles and Bradleys. They take pride in higher education, knowing different languages, being a leading market for IT talent—they take a lot of pride in that creativity. It’s just something that’s in the air there.

CM: You reminded me of the idea of the Revolution of Dignity. We think of dignity here as individual, but I see it more as wanting a society that lives with dignity, with freedom.

AC: The Revolution of Dignity, Euromaidan, 2013-14, was a spontaneous uprising—and an art festival. They had a lending library, they had all sorts of musical acts. There were giant murals to Ukraine’s iconic poets painted on the sides of buildings. It was a big art festival that kept these protesters living in the freezing arctic cold for months, standing up to a corrupt, Kremlin-backed wannabe dictator.

I watch the disinformation that clouded the Western understanding of Euromaidan—all the journalists from all these big outlets kept repeating each other about a “neo-Nazi, far right movement,” and there were Jewish groups in Kyiv saying for the love of god, this is not what it is, we’re here too, we’re organizing. It was a whole diverse movement of people from all walks of life. All those thinkpieces collapsed when Ukraine went to the polls and had an election, and all of the pro-democracy candidates got overwhelming amounts of votes, and the far-right bogeymen that the Western press was trying to convince you were the heart and soul of this revolution got barely one percent combined.

There is so much disinformation about Ukraine that spreads in the West. It’s scary how effective it is.

CM: People are asking about the scene in the movie with cannibalism—is it historically accurate that cannibalism took place during this time?

AC: I grew up with those stories as a little girl, of what people did during the famine to survive. Those are well-known and well-documented. There is debate in the Ukrainian diaspora of how much they want to talk about that publicly because there’s a sense of shame around it. I would again urge everyone to read Bloodlands by Timothy Snyder—he describes the cannibalism. He describes an orphan in an overrun orphanage of starving children being devoured by the other children. There would be gangs of these orphans. Cannibalism unfortunately is what people resorted to. Because part of the slow death of hunger is madness. You go mad.

My grandfather in his memoir wrote about having to stop his brother from eating the dirt, because he was hallucinating that he was seeing food. The madness takes over. One of the producers on our film recounted that her grandmother was waiting in a bread line in Ukraine, and a group of cannibals came out of the woods and tried to kidnap her, but the rest of the line fought back and saved her from them. People were driven mad by hunger.

There were rules: all the wheat fields were being patrolled by Soviet soldiers, and if you went into the field after dark to try to steal a few grains of wheat, you’d be shot on sight. That was very common. So people were boiling twigs, leaves, mud, dirt. I interviewed one survivor who describes how she and her brothers were boiling a pot over an open fire of twigs, leaves, and dirt, and Soviet agents came and dumped out the whole pot. They would confiscate the stuff people used to feed themselves. Plates, forks, knives. They wanted total starvation.

They didn’t have a nuclear bomb then. It was a time of Henry Ford-level efficient killing. The Nazis were engineering their concentration camps; the Soviets were engineering starvation to kill as many people as possible and weaken the country and then colonize it. Over time they repopulated those areas with Russians, and that’s why today Donbas, eastern Ukraine, is heavily ethnic Russian and Russian-speaking. Those are Russians who have been in those regions since 1933. My grandfather was born and raised in Donbas, eastern Ukraine, speaking Ukrainian, thinking Ukrainian, writing in Ukrainian, and then Stalin came and changed everything: wiped out the Ukrainians and over time brought in the Russians. So now the area is largely ethnically Russian, and Putin then built on Stalin’s legacy by invading, by saying we have to come in and rescue the Russian speakers. Just like Hitler had to “rescue the German speakers” when he seized part of Czechoslovakia.

CM: Do you want to say anything else on the idea of whether or not we should be calling it a genocide? I want to remind folks: what Andrea is describing is well-documented. There are Soviet archives that have been opened up for thirty years now. They blockaded towns. They blocked people from leaving their towns. They went into their homes and took their food. This is not a historical debate. There’s a certain inhumanity in even making it a debate.

It’s emotional to listen to you talk and compare it to these questions.

AC: The existence of the debate itself shows the impact of Russian disinformation for all these generations. This was a largely hidden atrocity. And if you don’t want to take my word for it, there’s a historian at Stanford University by the name of Norman Naimark who wrote a book called Stalin’s Genocides, and one of the genocides is this famine. It’s important for people to understand that Stalin committed several genocides. What we’re talking about tonight is just one of them. We could do an event like this for every single genocide, including what was then in Kazakhstan, including what happened to the Crimean Tatars, and so on.

Get Norman Naimark’s book. It’s a unique, encyclopedic look at Stalin’s genocides. The book delivers exactly what it promises.

There is no “land for peace.” Land for peace does not work. It is delusional.

CM: The chatbox is saying our response indicates we are working for the CIA.

AC: That’s funny. I don’t know what to say to that. Historians are not CIA agents. Historians are historians. And facts matter.

CM: We want to have a serious, intelligent debate about serious matters that are really contested.

There are some interesting questions. Do you see any parallels between Russian aggression and propaganda in Syria and Ukraine?

AC: Without question. What the Kremlin was able to get away with in Syria is paying dividends today. There was a popular uprising in Syria as part of the Arab Spring, a revolution there pushing back. Then Assad got protected by the Kremlin, and now the Kremlin owns Syria. Obama pledged a red line, the use of chemical weapons, but Assad marched over that red line and Obama did nothing. Obama’s foreign policy was spread very thin, with his team prioritizing the Iran deal (and fighting ISIS, which had sprouted up in the vacuum of power in Iraq and Syria as well). As a result, the Kremlin was able to nab Syria and now has a military base on the Mediterranean which it uses to great effect, to spread its influence across Africa, including in Sudan, where the Kremlin, since the start of the Ukraine invasion in 2014, has been trying to circumvent Western sanctions by pillaging African nations through corrupt local proxies on the ground.

The Wagner group are the ones carrying out these Kremlin dirty wars, this African colonization. There have been horrible stories, like in Central African Republic, where Wagner soldiers broke into a maternity hospital and raped women who had just given birth. That’s been reported on in the press. And it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Wagner soldiers also shot several Chinese nationals in Africa, which China was upset about, because China is trying to cash in on the pillaging as well. China and Russia are in a competitive partnership across Africa, trying not only to seize as much wealth and build as much influence as they can in those countries, but also to drive a wedge against the global democratic alliance and to go after America’s standing in the world.

These are all important dynamics to pay attention to, because Syria was a big win for Putin, one that Europe and the US allowed. All the disinformation, all the useful idiots on the far left and far right, assisted that. They allowed it to happen. Syrians, Syrian children paid the price. The mass torture, the mass starvation, all of it that continues to this day—it’s the world’s karma. It’s something that we absolutely can’t look away from.

There’s a wonderful documentary, the story of a Syrian mother who picked up a camera and documented her life inside Syria. She did it with a baby strapped to her chest. The movie is called For Sama. She made this documentary about their life in war-torn Syria. Again, like Gareth Jones, the power of bearing witness! And we can’t look away.

This is why we fight! You asked about why Ukrainians fight so hard. It’s this history, and generations of trauma, yes. I interviewed a lot of Ukrainians, people from all walks of life: why did you go to Maidan, why did you risk your life going to Euromaidan? They said it was because of the stories of what their grandparents went through under the Soviets. They showed up there for their families, to avenge their families, to get some sense of justice for what was done to their loved ones. For Sama. That right there sums up why we do what we do.

Why would I spend fourteen years trying to get this movie made? I didn’t do it to get a foot into the industry. I could have broken in a million other ways. I had a day job working in media, in newsrooms. I was at Condé Nast, I was at AOL Money & Finance. They were trying to put me on TV, on news shows, to tell folks how to file taxes, how to get makeup done and be blonde and sparkly, and I could not spiritually do that—because of my grandfather. All of us have our own For Sama story that engages us with this larger world, that forces us to do something, to take back our agency and refuse to be powerless.

CM: What lessons can the US learn from the genocide in Ukraine? What can we learn from that, with our own history of displacing and exterminating Native Americans?

AC: We have to make space for all genocides, to take a moment to sit with this history and be conscious and aware of the effects that history has had on today. This genocidal invasion did not just happen overnight. It’s history playing out. History explains why Ukraine is so important to Russia in their imperialist ambitions, and why Putin brought back the cult of Stalin. In terms of understanding ourselves as a country, we are on land where populations of families, communities, were wiped out to such a severe extent that it literally changed the temperature of the planet. In place of those communities we’ve brought this greed-is-good, exploitative, top-down, the-biggest-gun-wins culture instead. That’s not right. To honor those who were killed is to learn their history, to hold space for historical truth, and also to try to bring back what those communities stood for and the balance that they lived in—bring that balance back into our own lives, bring that community back into our own lives, and come together and say No to that genocidal strain in our history that rears its ugly head today in this rampant, violent gun culture where people just shoot you if you pull into the wrong driveway.

People should not be surprised that that’s happening, and that it’s so widespread, because we are living in a land that was built on genocide.

CM: Do you see any linkages or connections between Russian disinformation narratives today around Ukraine, and the tactics that were deployed in the 1930s?

AC: Without question. There’s a genocidal zeal. We’re going to kill the Ukrainians, slaughter them so there’s nothing left. They had that same zeal back in the 1930s. All genocides start with hate speech and propaganda. The Soviets produced films dramatizing Ukrainian farmers burning their own crops rather than give it over to a collective farm, pairing them with images of locusts. That’s genocidal imagery: they are bugs, we have to go in a squash them. On top of the proper soldiers that went in and carried out this genocide, there were other gung-ho true believers, full of genocidal zeal. We see the same energy today coming out of the Z movement in Russia.

There’s a pride in imperialistic, genocidal ambitions, and there is casual, proud use of genocidal language, cheering on the Russian bombs killing civilians and leveling towns. They are cheering it on. Stalin and the Russians didn’t forget that during the Russian revolution, Ukrainians, for a time, fought for their independence and won. There were several years where Ukraine was independent; they were winning the war for independence during the chaos of the Russian revolution. Russia never got over that, never forgot. They love this idea that we’re finally going to bring Ukraine to its knees. Ukraine is ours. Crimea is ours. It’s very hard, even for some of the so-called Russian opposition figures, to say, “Give Crimea back.” They don’t really want to.

CM: What do you think peace activists in the United States should do? And how do you think the war will end?

AC: Continue doing events like this. You could have a screening of For Sama. You could invite all sorts of people like me to have gatherings like this. You could also be creative—I was thinking a lot about Ukraine’s resistance and the civil rights resistance: music, singing, choruses, any types of songs. You could go caroling at some of these protests. They sang so much at Euromaidan, and they’d enlist local bands. Protest, standing up for human rights—turn it into an art festival. Express yourselves, be creative, hold your events in creative spaces. Inspire each other to be creative. It’s okay! I know we’re dealing with very heavy issues. But when Ukrainians were staring down the barrel of a gun at Euromaidan, they were having a big old block party doing it, with all these musicians and acts coming through.

Joy, basically. Joy, falling in love, art, beauty. Bring as much of that beauty and energy as you can into the world, because it’s all resistance. For Sama: a mother picked up a video camera and decided to be creative. Be creative. Don’t hold back. Unleash that part of yourself. And have empathy for yourself and others. Recognize that you are loving and lovable. Hold that space for yourself and others, see yourself that way. That’s where your power is going to come from.

And yes, as part of these gentle discussions you have conversations about trauma. Bring that to the surface—you have no idea what lives you might save by doing that.

As for how the war ends, Putin is notoriously stubborn. He always pushes deals too far. It could end if he dies. That’s a long time to wait. He’s increasingly isolated because he’s losing, and he’s out of touch. He’s like the mad King George over there. And they know it, increasingly. Phone calls are getting leaked between these oligarchs that are hilarious, how much they’re trashing Putin and the others. There’s also a civil war among the elites, the Russian ministry of defense, and the Wagner group. That’s going to be heating up as the sharks circle to see who’s going to take the place of Putin.

All of those things I just described are going to further weaken the war effort. The greatest ally the Russians have, given their chaos, dysfunction, and corruption, are the Republicans here in the United States who write op-eds asking why we’re sending our tax dollars over there. Tucker Carlson, Matt Gaetz, Mike Lee—all of the Kremlin disinformation they’re spouting, trying to sow doubt in the united front, is what’s dangerous. If we were to get a president and congress that lost their humanity and forfeited the fight and gave Ukraine away like the US government collectively gave Syria away, it’s going to be a huge victory for the Kremlin that they’re going to build off of to go even further and deeper with their imperialist ambitions, just like they’re doing now across Africa thanks in part to having that big military base in Syria from which to operate.

So I don’t know when the war is going to end, but I know that we have to have a long game, and we can’t make the same mistakes as with Syria. But I do know that if Putin dies, it does give the Russians a reset opportunity. We absolutely have to push them out of Donbas and out of Crimea. Because if we don’t, we’re leaving them staging grounds to recoup and rebuild and relaunch another invasion. It’s so important that people learn from World War Two, with Chamberlain. There is no “land for peace.” Land for peace does not work. It is delusional.

You cannot do land for peace. If you want the war to end, put pressure on Russia, Russian businesses, Russian figures that are for the war. Don’t talk to NATO, don’t talk to Ukraine about this. They’re not the ones causing the war. The US did not want this war. They tried to give Zelenskyy an exit, they tried to get Zelenskyy out. They did not want this. Put the pressure on the Russians, and Belarus. Those are the ones that created the war.

CM: What do you think of Zelenskyy’s leadership?

AC: It’s just so surprising. I’m very surprised. Working with Vanessa Kirby, Peter Sarsgaard, James Norton—these are deeply intelligent, thoughtful, sensitive people. They are brilliant artists who intuitively capture the moment. Zelenskyy is a great artist. When you have that artistic muscle—not all great artists are great people. There are some great artists in Russia, for example, that are for the war. But many great artists are in touch with their humanity, and that’s where it comes from. Zelenskyy was able to rise to the occasion.

And he represents modern Ukraine. Zelenskyys are a dime a dozen across Ukraine! That’s why there is all this creativity. “Russian warship go fuck yourself!” The border guard who did that represents this young Ukraine. It’s really a generational battle between this Western-facing Ukraine versus old stuffy KGB-Man.

CM: With great sincerity, Andrea, I thank you. I feel expanded by your ability to articulate things in a humanistic way, and this was an amazing event. I learned a lot tonight, and I appreciate it.

AC: I’m so glad. Thank you all for being here. This was such an honor. I’m so grateful for all of you. Keep standing in your truth, keep demanding peace, keep shining your lights out there. We desperately all need to be doing that right now. And really search for the joy. Don’t let them deprive you of joy. Be joy machines wherever you are.

Have a wonderful evening, thank you.

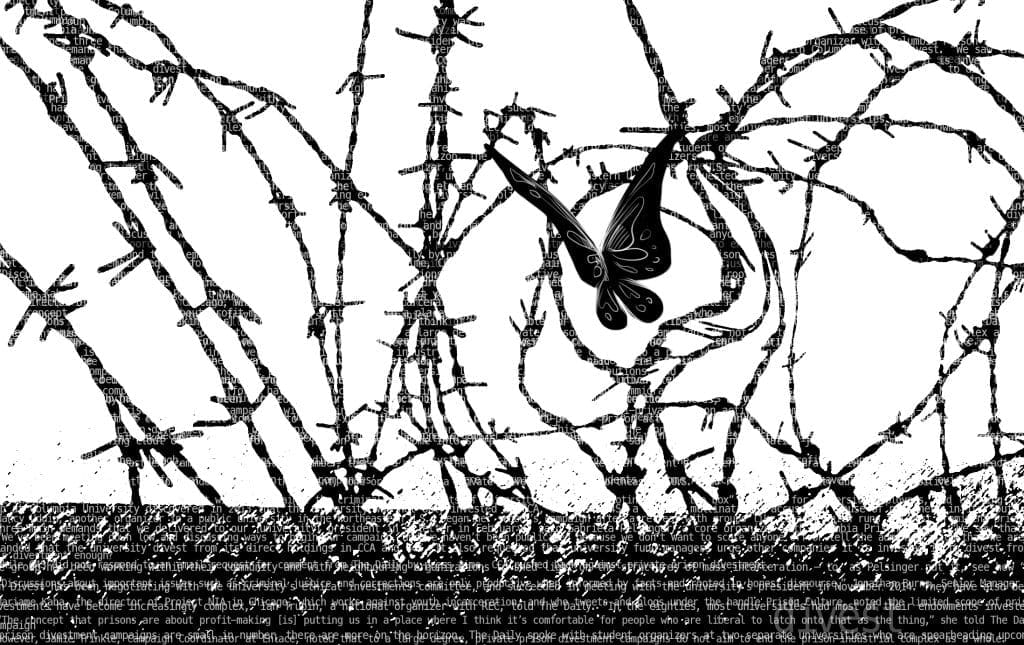

Featured image: still from the film trailer for Mr. Jones