Originally posted on Property Is Theft (website deleted by authors)

14 March 2010

Influenced by Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy, Mohandas Gandhi is perhaps the first person to put the principles of nonviolence and non-cooperation into effect of a mass scale. Explaining this principle, in For Pacifists, he wrote:

“The science of war leads one to dictatorship, pure and simple. The science of non-violence alone can lead one to pure democracy…Power based on love is thousand times more effective and permanent than power derived from fear of punishment….It is a blasphemy to say non-violence can be practiced only by individuals and never by nations which are composed of individuals…The nearest approach to purest anarchy would be a democracy based on non-violence…A society organized and run on the basis of complete non-violence would be the purest anarchy.“

The ideal inspired not only Gandhi’s own movement for independence in India, but also the actions of groups such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the American civil rights movement. It remains a popular idea today, within both a wider activist circle and the specific philosophy of anarcho-pacifism. However, it has its critics.

For example, George Jackson of the Black Panther Party criticized the idea that nonviolent resistance would have an effect upon the enemy having to kill those who used no violence:

“The concept of nonviolence is a false ideal. It presupposes the existence of compassion and a sense of justice on the part of one’s adversary. When this adversary has everything to lose and nothing to gain by exercising justice and compassion, his reaction can only be negative.“

However, my argument here is not that nonviolence is ineffective as a tactic. Indeed, it can yield considerable success given the right arena. It is that pacifism, as an absolute, is fundamentally immoral and unjustifiable within the context of the world we live in.

Pacifism and nonviolence

Though I will be using both terms in this article, it should be noted that “pacifism” and “nonviolence” are not interchangeable ideas.

Nonviolence is a form of resistance, a way of fighting back against injustice or oppression without the resort to force. The sit-ins of the civil rights movement, as a way of opposing segregation within business establishments, are a prime example of this. Nonviolence is employed by pacifists, of course, but it is important to separate it from that and understand that those who advocate the use of force and violence when necessary can also use nonviolence in specific situations.

Pacifism, on the other hand, is a principle adopted by individuals. Somebody who self-identifies as a pacifist will never, if true to their ideals, resort to violence. Even when threatened or attacked, they will not fight back. Pacifism can be summed up with the Gandhian quote that “there are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for.” After all, as he saw it, “what difference does it make to the dead, the orphans, and the homeless, whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or the holy name of liberty and democracy?”

There is a worthwhile discussion to be had about nonviolence as a tactic, and where it is and is not effective. However, it is the principle of absolute pacifism, not the tactic of nonviolence in specific situations, that I am calling morally indefensible.

In war and genocide

Whatever else one might say about him, Gandhi could not be accused of mincing his words or shying away from the logical conclusion of absolute pacifism. In Non-Violence in Peace and War, Gandhi offered the following advice to the British people:

“I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions…If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them.“

This is one of the comments which inspired George Orwell to declare that “pacifism is objectively pro-fascist:”

“This is elementary common sense. If you hamper the war effort of one side you automatically help that of the other. Nor is there any real way of remaining outside such a war as the present one. In practice, ‘he that is not with me is against me’. The idea that you can somehow remain aloof from and superior to the struggle, while living on food which British sailors have to risk their lives to bring you, is a bourgeois illusion bred of money and security.

…

“I am not interested in pacifism as a ‘moral phenomenon’. If Mr Savage and others imagine that one can somehow ‘overcome’ the German army by lying on one’s back, let them go on imagining it, but let them also wonder occasionally whether this is not an illusion due to security, too much money and a simple ignorance of the way in which things actually happen. As an ex-Indian civil servant, it always makes me shout with laughter to hear, for instance, Gandhi named as an example of the success of non-violence. As long as twenty years ago it was cynically admitted in Anglo-Indian circles that Gandhi was very useful to the British government. So he will be to the Japanese if they get there. Despotic governments can stand ‘moral force’ till the cows come home; what they fear is physical force.“

Orwell’s support for the British state as the best way of challenging a force such as fascism can be challenged. Indeed, in Killing and dying for “the old lie” I made a point of the distinction between antifascism and pro-imperialism during the war. However, this only serves to shift the argument from war waged by states towards armed resistance by organized antifascists outside the state structure. It does not alter the fundamental fact that allowing “yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered” cannot be classed as a victory just because you “refuse to owe allegiance to them.” In the end, totalitarianism still reigns and the slaughtered will go unavenged.

This is what makes his comments about the Holocaust, in 1946, so despicable:

“Hitler killed five million Jews. It is the greatest crime of our time. But the Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs. As it is, they succumbed anyway in their millions.“

The idea that this would have ”aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence” has little weight. By 1939, those whose actions would have been motivated by antifascism and anti-racism already were aroused to it. Conversely, those acting against Germany for other reasons were largely unconcerned even when aware of the plight of the Jews. All that collective suicide would have done, ultimately, is facilitated genocide. As Malcolm X argued, “I believe it’s a crime for anyone being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself.”

Collective self-defense

Militant self-defense, both individual and collective, is entirely in line with the anarchist principle of direct action rather than relying on the state or other “authorities” to look after us. In the words of Rudolph Rocker, “by direct action the Anarcho-Syndicalists mean every method of immediate warfare by the workers against their economic and political oppressors,” and so “any means is justifiable that can prevent the organized murder of peoples.”

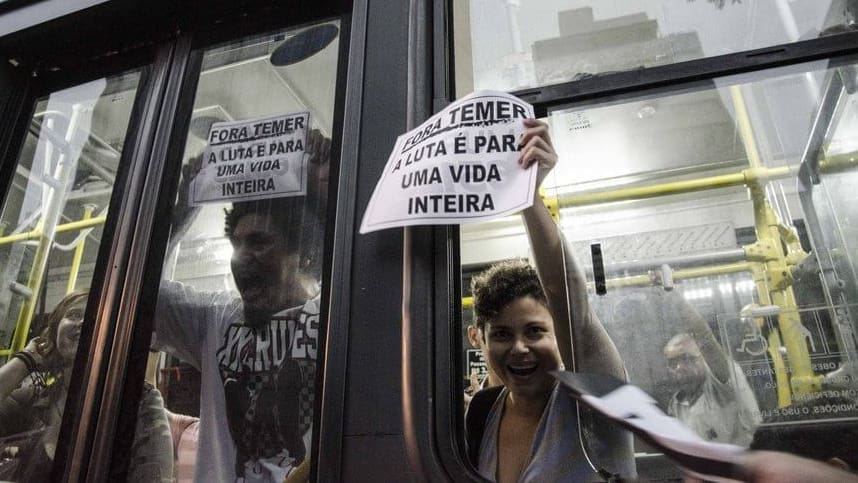

An image from the television series Deacons for Defense, about a small group of African American men in Jonesboro, Louisiana who became a popular symbol of the growing frustration with Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent strategy and a rallying point for a militant working-class movement in the South

Though from the specific perspective of antifascism, I argued much the same point in On violence and censorship when I advocated physical resistance to fascist violence:

“Organized fascist and racist groups pose a physical threat to ethnic minorities, LBGTQ people, and, primarily, to the organized working class. In the face of this, and given the documented complicity of the state in such repressive violence, resistance organized at a grassroots level is the only sensible option.“

The history of Anti-Fascist Action in Britain only emphasizes this fact. And the same principle applies to any group which poses such a threat.

Returning to the civil rights movement, an important parallel were the Deacons for Defense and Justice. They operated under the principle, as articulated by Stokely Carmichael in Black Power (PDF), ”that the ‘law’ and law enforcement agencies would not protect people, so they had to do it themselves.” Lance Hill, in The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement says of nonviolent civil rights organizations, “the hard truth is that these organizations produced few victories in their local projects in the Deep South—if success is measured by the ability to force changes in local government policy and create self-governing and sustainable local organizations that could survive when the national organizations departed.”

Conversely, “the Deacons’ campaigns frequently resulted in substantial and unprecedented victories at the local level, producing real power and self-sustaining organizations.” For example, “in Jonesboro, the Deacons made history when they compelled Louisiana governor John McKeithen to intervene in the city’s civil rights crisis and require a compromise with city leaders—the first capitulation to the civil rights movement by a Deep South governor.” Carmichael points out that “the Deacons and all other blacks who resort to self-defense represent a simple answer to a simple question: what man would not defend his family and home from attack?”

It is this question which brings us to the core point on why the absolute pacifism is immoral. Unlike a pragmatic recourse to nonviolent resistance only in situations where it will be effective, it offers no recourse for the defense of innocents from injustice and brutality. And, ultimately, there is nothing heroic, even in principle, in offering yourself to the butcher’s knife.