Between Repression and Paternalism: European Asylum and Immigration Policy after the Lampedusa Tragedy

by Javier de Lucas for Critical Legal Thinking

14 December 2013 (original post)

After ships carrying hundreds of refugees sank off the Italian coast recently, we must demand a change in asylum and immigration policies or surrender to the logic of barbarism.

Crocodile Tears

In the space of just over a week the world watched in astonishment as two ships sank off the Italian coast, giving rise to staggering death-tolls (359 on the 3rd of October, more than 50 on the 11th) and various expressions of grief. Among the mourners were those directly responsible for asylum and immigration policy and its legal tools within both Italy and the EU, who travelled to the island to offer their condolences and vowed never to forget the hundreds of coffins heaped on the shore. However, these individuals who, on the one hand, promote institutional xenophobia and racism through the construction of walls and use of gunboat surveillance,1 but have no trouble shedding a tear for the dead when the cameras are on, represent a hypocrisy which has now become unbearable.

My first proposal is that we do not let ourselves be deceived by these crocodile tears which insult both the victims’ dignity and our own.2 The real issue is how these deaths relate to the asylum and immigration policies of the EU and its member states. We must not accept these reactions which treat the deaths as if they were the result of natural causes or some cruel twist of fate. The increasing exasperation and outrage that overwhelm European citizens who helplessly bear witness to these catastrophes does not arise from a sense of powerlessness in the face of tragic yet inevitable “natural” disasters. These deaths are rather murders whose perpetrators who cannot go unpunished. Our struggle is one of impotence against impunity.

It is my belief that there is a causal link between these mortalities and the persistence of a policy based on a filtration system (only enough individuals are allowed to enter to satisfy the available and required jobs and not a single more, while those who ‘slip through’ are immediately thrown out) combined with an obsession which reduces in practice all immigration policy to a ‘struggle against illegal immigration’ and ignores the real causes of migration. Because these deaths are not the first. We need only consider that from 1990 to the present, more than 8,000 corpses have reached the shores and surrounding waters of Lampedusa and the most reliable sources estimate the figure to be over 17,000 in the last ten years across Europe.3 Let us not forget that in the shipwreck of the 3rd of October of 2013, the greatest disaster to have hit the shores of Southern Europe, the number of victims rose to 500 men, women (some of whom were pregnant) and children, the majority of whom, except those of Syrian origin, had traveled more than 4000km in an attempt to flee the poverty brought about by the conflict in Somali and the totalitarian regime in Eritrea. Paradoxically, the sheer magnitude of this tragedy placed the bar too high for subsequent shipwrecks, the first just over a week later, to attract media attention.

There will always be a voice of realism reminding us that the responsibility for these tragedies falls not on the EU or the West, but primarily on the regimes and countries which force these people to live in misery and hunger, without basic rights or life expectancy. However, I refuse to accept that our answer to this new community of emigrants from Eritrea, Somalia and Syria, people who live in an Anabasis like that described by Quirico, is simply ‘Try elsewhere, we already do more than our bit to support the cooperation and development program.’ We cannot ignore the shame that falls upon us, we who pride ourselves on the values of the EU; on the guarantee and defense of human rights and democracy yet forget those of others when they turn to us. But how can we deliver justice? Is there a possible alternative to current asylum and immigration policy? Do we have to change its legal instruments?

Considering the issue in legal terms: one omission and two sophistries

I would like to highlight one serious omission and two misapprehensions, or worse sophistries, which in my opinion pose a barrier to accountability on immigration issues. They hamper current debate and, as in Anderson’s parable, provide a new set of clothes for these naked politicians, along with no small number of media sources.

It is this omission that allows us to continue splitting hairs over who is responsible, whether it is the EU, Italy, Malta, the fishermen, or the islanders who should act. No. It must be made clear that all those who fail to assist the victims are criminals through their violation of the law. If those citizens who break the law are deemed criminals so too then should those politicians belonging to the EU or its member states who have breached its regulations. And the offenses of those who prevent ordinary citizens from adhering to the law are all the more serious.

This is the real issue. No more talk of humanity, piety and solidarity. We are dealing with a legal offense of the first order that demands accountability and appropriate sanctions. This is essential if we are to stop the poison of impunity and popular disillusionment spread by this tragedy because nothing can be done and media attention shifts as soon as the next disaster surpasses a death-toll of 350.

It must be made clear that it is a matter of criminality, of offences which demand punishment because non-assistance to a person in danger at the very least violates a current legal standard. Indeed, through the repressive control exerted by Frontex and states such as Italy, Malta and Spain, the EU in its reaction to these shipwrecks appears to have repeatedly forgotten the legal duty to rescue enshrined in the oldest laws of the sea, basic common laws which for example overrule the Fini-Bossi law; and today by complex treaties of international law of the sea such as the 1982 Montego Bay Convention on the Law of the Sea and the SAR and SOLAS Conventions.

The continual disregard of these obligations, which has been largely concealed by the tone of the media coverage through its emphasis on the most engaging ‘humanitarian’ and ‘tragic’ dimensions of the incident, is supported by two sophisms. The first of these is the insistence on referring to ‘the tragedy of immigration’. No. In large part, the victims of these shipwrecks are refugees because they are fleeing from failed states, civil wars and conditions which put their human rights at risk, as is the case in Eritrea, Somalia, Syria or Mali. It could soon again be Libya, or terrifyingly even Tunisia or Egypt. And what about Eritrea? We need only read the reports published by The Economist, such as ‘Eritrea and its emigrants: Why they leave’ on the arrival of Eritreans to Lampedusa or those mapping the political evolution of the country such as ‘Eritrea: A State of Siege’ or ‘Eritrea: Robocall revolution’ which clearly outline the reasons compelling hundreds of thousands of Eritreans to leave. Many of them fled to non-European zones such as the 125,000 who traveled to Sudan, the 87000 to Ethiopia or the 40,000 to Israel. From this former Italian colony they have also set out for Lampedusa in the hope of escaping a country which has now transformed into a concentration camp worse than North Korea. Thus refugees, like those arriving from Syria, are an increasingly important contingent.

Whether they are immigrants or refugees is not a trivial distinction. Of course the seriousness of the tragedy changes depending on which group is involved. However, it is this ambiguity which reveals the fundamental prejudice upon which immigration and asylum policies are founded. Indeed, official doctrine considers immigrants to be economically motivated as their movements are primarily dictated by work reasons. Refugees on the other hand are considered to have been forced to leave their countries as a result of political persecution. As a result, the EU and the majority of its member states have tried to regulate the entry and sojourn of the former group according to a cost/benefit evaluation, following what has come to be known as a communicating-vessels model. According to this system, precisely enough will be allowed enter that will satisfy the demands of the market and prove profitable but not a single more, a perfect balance must be maintained. Refugees however are viewed solely as a financial burden and policies have increasingly restricted eligibility for asylum applications within the EU. These individuals are simply not legally able to enter our Paradise. We have made it impossible for them and their only option is to try and reach the border by whatever means possible. And even those which do arrive we do not allow them to show it (lit they are not allowed present themselves as such) they are locked up in camps under inhumane conditions like those seen in Lampedusa and treated as illegal immigrants that face fines of up to €4000 and expulsion.

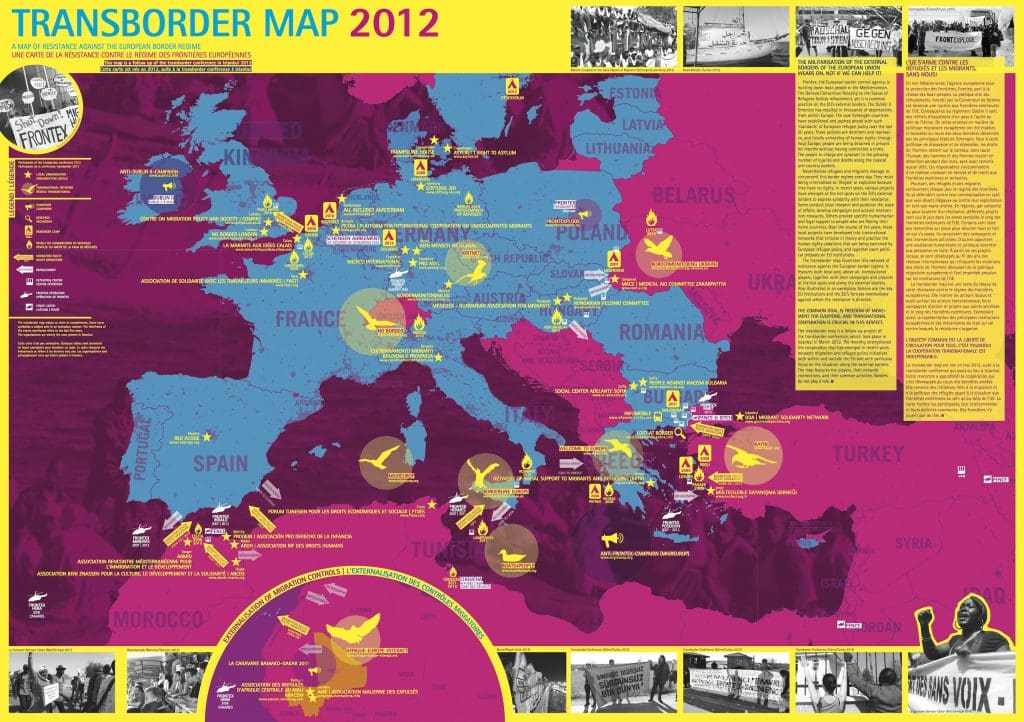

In both cases, the EU maintains control and vigilance as its highest priority. This is the role of FRONTEX which coordinates the reinforcement and even relocation of borders to third countries despite their dubious human rights records such as Morocco and Lybia. As a result, efforts are focused on controlling illegal immigration and its networks, as well as preventing the misuse of asylum procedures by those who are ‘just immigrants’. The closure and reinforcement of these borders (Cueta, Melilla, Malta, Sicily and its surrounding islands or Evros and the islands of the Aegean Sea) results in the rise in illegal journeys and changes of route. The majority of refugees today travel an average of 4,000km to reach the same ports where crowds of immigrants prepare to make the leap. And a significant proportion (almost 20,000 in the last 10 years according to the Libération report) die in the attempt. The twin catastrophes at Lampedusa are just another two examples.

This reveals the second sophistry produced by those who suggest that the issue is a lack of humanitarianism or altruism and claim that our capacity for solidarity and generosity is weakened in times of crisis. They insist that Europe (Italy and Spain) cannot carry the weight of the world’s misery on its shoulders and that we already do enough. But this is simply untrue. Not only are we guilty of failing to save lives, which is our most fundamental duty, but in the case of refugees we are talking about the violation of specific legal obligations which should carry significant legal consequences.

We must remember that the EU and its member states have very real legal obligations towards those seeking asylum and must be held accountable should they fail to fulfill them. These responsibilities were originally set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (see articles 5 and 6), such as the principle of non refoulement, the duty to not reject those who request asylum as stated in article 33.1 of the United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees from the 28th of July 1951 followed by the Protocol of the 1st January 1967 which lead to the Advisory Opinion on the Extraterritorial Application of Non-Refoulement Obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. If any more evidence was needed, we may also note that this infringement also breaches the provisions of article 3 of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of the 10th December, 1984.

In the case of the refugees fleeing Eritrea and Somalia, the EU has not even considered the establishment of humanitarian corridors or rescue operations in the Mediterranean beyond the Mare Nostrum operation funded by the Letta government. Similarly, the question of immigration routes which currently pass through central Africa and recently resulted in a hundred deaths in the desert of Northern Mali, still goes unanswered.

It is the duty of us, the citizens, to declare that the states which maintain these asylum and immigration policies do not deserve the title of democracy or even to be considered law-abiding states as they fail to respect the basic human rights which are the very core of the law. As they have ratified and incorporated the international conventions on refugees and on the laws of the sea into domestic law, their violation of their own laws is a crime for which they must be held accountable. If these illegal acts are to be stopped we must demand a change in asylum and immigration policies and accordingly assess the agendas proposed at the next European elections. Otherwise we are surrendering to a logic of barbarism, and we will be the savages.

Javier de Lucas is Professor of Philosophy of Law and Political Philosophy at the Human Rights Institute, University of Valencia.

Translated by Lucy O’Sullivan