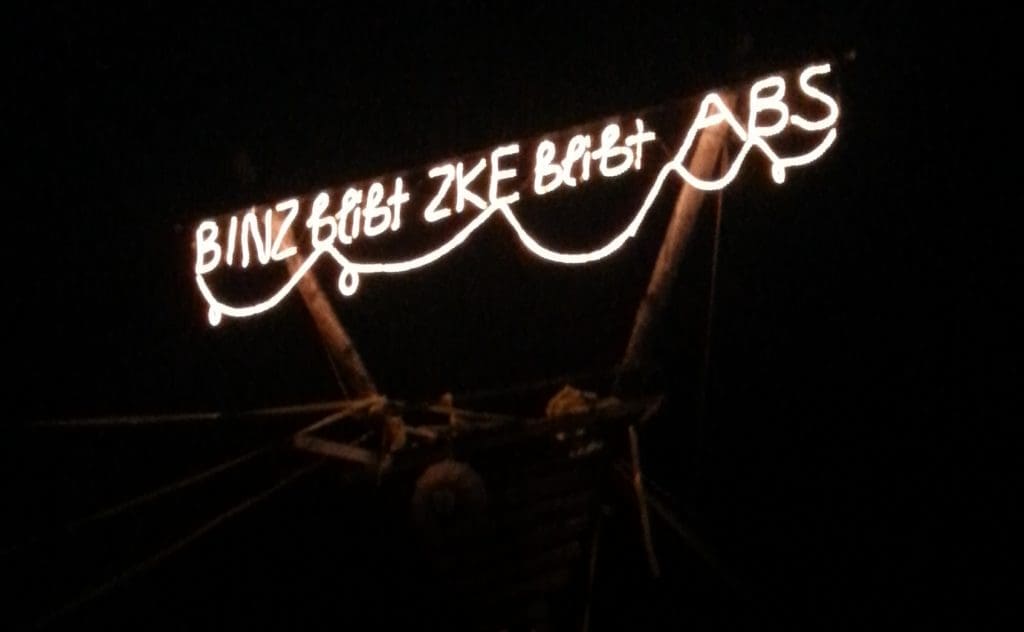

AntiNote: A year ago, our friend and comrade Deckard of the Permanent Crisis blog wrote a thoughtful response to a manifesto of sorts that sprang out of my (Ed’s) experience of the so-called Binz Riots of 3 March 2013 in Zürich.

This conversation is worth reanimating partly because the issues at hand are still relevant, despite the puzzling disappearance of the Binz Riots from civic memory and the Binz struggle itself having quietly exited the stage last June (you can read my take on the Schoch Family’s relinquishment of the squat here). Another long-standing Zürich squat—or constellation of squats, rather—at the Labitzke complex is currently faced with an order to vacate by the first of April and has issued a call for resistance.

But Deckard’s piece is also worth digging up because it raises a lot of important issues that we should all still be thinking about. He makes some points with which there could be considerable contention—it was, after all, a rebuttal of sorts to my “Squat the World!” histrionics. It confronts us with ideas we shouldn’t stop wrestling with. We hope this discussion will continue; we invite your comments.

By Deckard of Permanent Crisis

My friend and comrade Ed Sutton poses an interesting perspective from which to think about a global progressive movement in his article for Occupy.com. The movement isn’t coming, it’s right in front of us, he argues. If only we’d open our eyes we could see it. Although I differ in my analysis of the reasons behind the Occupy movement’s ostensible fall from prominence in the media, I think that the perspective he suggests is well worth further exploration and debate. As I take it, the central question animating Ed’s reflections on the squatting movement in Europe is, succinctly put, what form should our movement take? Through what social practices can we realize the potential for overcoming the social tensions—between plenty and want, between love for one’s neighbors and hate for strangers—exploding into popular consciousness in this moment of upheaval?

His answer is the “coalescence of various currents and codes based in self-organization” and an “anarchistic ethos” that have taken concrete form in the squatting movement. Ed focuses on the squatting movement not only because it’s an international concern within Europe, but because of the affinity between it and the tactics of Occupy groups in the US.

For him the value of squatting is its potential to resist the depredations of neoliberalism: “[a]s austerity sweeps the continent, squats—among the last remaining scraps of common space (Freiraum) and therefore burrs in the saddle of neoliberalism’s charging horse, privatization—are being systematically cleared out.” He also gives the sense that these “autonomous communities” are a real threat to the status quo, as seen in Greece’s squat-centered anarchist movement.

Of course, I fully agree with Ed about the threat that neoliberalism poses to the potential for a healthy human community. He rightly notes that we are currently experiencing this threat in the form of austerity policies taking a great toll in human life and the potential to create a future better than the present. Ed’s argument seems consistent with an approach that claims that genuine human community is to be found in spaces outside of the institutions of our neoliberal, increasingly privatized society.

But I would like to argue in contrast that the best chance we have to challenge the dominant social structure is precisely from within it. Global systems of production, circulation, administration, etc., hold the means to provide material necessities for everyone on earth. Our ultimate goal is to make them serve humanity, rather than their own perverse logic of accumulation. Therefore, our salvation will be found not in pure spaces outside of society, but in the future realization of a genuine global community. Our task is not to occupy spaces of freedom, but to work together to free humanity’s future.

Before elaborating on this vision, we need to clarify what is meant by “neoliberal society,” a concept that both Ed and I use to critique the current organization of our world. In my view, neoliberalism is the latest chapter in the story of the creation of progressively larger and more all-encompassing forms of capitalist social organization. It has effectively bound all humans together into one system in which we have become ever more interdependent. This can be confirmed simply by thinking about the many different countries from which the products that we use or consume every day come. Needless to say, the manifestations of this interconnectedness are often horrific and irrational. Financial decisions on one side of the globe quickly metamorphose into human devastation on the other side, and much production for the global market takes the form of sweatshop labor.

Despite these appalling problems, I believe that we should look to our mutual interdependence as our best hope for liberation. Even if it were possible to withdraw from the global system, to do so would only make our struggles irrelevant to global majority, for whom such an action does not hold much meaning. There are billions living in economically poor countries for whom such a withdrawal could only mean absolute impoverishment and relinquishing the tools needed to better their lives. If your daily living depends on scavenging garbage or informal grey market labor, you won’t think of withdrawing from the system as liberating—in fact you would already be on the absolute margins of that system. It is not merely our duty to reach out to those impoverished by the global capitalist system, it is also our only way to form an alliance strong enough to defeat the forces that would defend the monstrous status quo.

In the USA itself squatting and public occupations will not do much for those in desperate need of jobs or access to health care. Even if an aggressive movement based on resisting neoliberalism forced the powers that be to address the issue of housing foreclosures—undoubtedly a worthy goal in itself—how would that alter the system fundamentally, other than alleviating some of the suffering associated with it? That’s not to say that struggles against foreclosure aren’t important in inspiring and enlightening many people. But when we frame our big-picture strategic orientation, we need to be even more resolute and ambitious in our aim. We don’t want to treat the symptom, but the underlying disease.

Our strategy must be to strike precisely in those spaces where the globalized pathways of capital cut across, over, and through community boundaries. Imagine for instance, a serious global campaign targeted at a multinational corporation like Walmart. When we stand on the floor of a Walmart store or in one of their warehouses, we stand in the heart of neoliberalism, a place that serves human needs only indifferently in executing its one true purpose—the accumulation of capital.

When we stand there, the human relationships that exist beneath the surface of society become a little clearer—not only the relationship of the customer to the worker, but crucially the relationships among the customers and workers in Walmart stores, suppliers, and warehouses in a multitude of countries across the world. Once these people who have been united in this perverse form can recognize the real human relationships between themselves, they have the potential to cut with the other edge of the world-devastating sword of corporate spatial domination. By turning the delocalized processes of production and circulation into the basis for uniting a new global movement, we would salvage the possibility to fight for the very things that the system promises us and never makes good on—the material and cultural requirements with which we can more fully develop our capacities as human beings, and the truly free time in which to do it.

My argument should not be taken as a wholesale rejection of squatting or occupation of public space as tactics. We have all been heartened at how groups using these tactics have brought questions about the legitimacy of neoliberalism and austerity politics into public consciousness. Nor would I suggest that a global solidarity campaign of the kind that I describe here would be anything other than an enormous and historical challenge, and one that would necessarily take a multitude of different but related forms. However, I think that the scope of the challenge is matched by the enormous importance of this undertaking for humanity.

Only a movement that locates itself in the vital arteries of neoliberal society would be able to reach the billions of humans that have, as yet, only been partially and contradictorily integrated into our global system. For these billions of, for example, Chinese, Indian, and African workers, the experience of the global system is very different from our own. Yet as we have already seen, we are irrevocably connected to them through the system. It is a system from which we must demand the means of creating a human community that will enable all to grow and express their true potential. We must not turn our back on this challenge, but rather proclaim our interdependence and fight for freedom together. Only by making common cause with our billions of brothers and sisters around the world will we find the strength to redeem our future.

Originally appeared 25 March 2013 on Permanent Crisis; reprinted with permission of the author.