AntiNote: The following is an extended excerpt of a radio interview, edited for readability. Transcribed and printed with permission.

Since this talk between host Chuck Mertz and author Iain Sinclair (from This is Hell! Radio’s 17 May 2014 episode) covered a lot of ground and went in many different directions, we have removed large portions of it for reasons of space and clarity. We therefore encourage you to listen to the whole thing right here!

Our ‘edition’ narrows the scope of the discussion, which centered on a latter-day exploration of the Beat Generation and their haunts, to just haunts. That is, we found the portions of Chuck and Iain’s conversation that centered on place, cities, and our place in cities to be most complementary to topics we cover on Antidote. Further, much of the discourse about the gentrification and commercialization of—and our alienation and expulsion from—urban landscapes lacks the poetic and emotional sensitivity that this conversation contains. We find this fresh, humane approach both affecting and appropriate to the real pain that underlies our objections to the neoliberal ‘development’ of cities we call home—a pain that can be expressed in the question, “Why doesn’t the city I love, love me?”

Chuck Mertz: On the line with us right now is British writer and filmmaker Iain Sinclair, author of the book American Smoke: Journeys to the End of the Light. Good morning, Iain; good afternoon in England!

Iain Sinclair: Good afternoon in England!

CM: You are a self-described British writer, documentarist, filmmaker, poet, flaneur (which is now my new favorite word), metropolitan prophet and urban shaman, keeper of lost cultures, and futurologist. But you’re also a psychogeographer. Explain to people what psychogeography is.

IS: Psychogeography has become a very trendy thing in Europe of late; it really emerged in the 1960s in Paris with people like Guy Debord and the Situationists. They had an idea of using geography conceptually—say, navigating Paris with a map of Venice, doing really strange things to try and combat what they saw as the commercialism and the deadness of cities. It’s inventing a kind of poetic way of dealing with cities.

And in the 1980s and ‘90s in England, the Margaret Thatcher era, when suddenly the Docklands were going up and the whole of London began to look more like a generic city anywhere in the world rather than old London, people started to undertake these strange projects. Generally, walking. For example, I walked around the edge of the M25 orbital motorway—I thought of a motorway as a place to walk that gave you a sense what the city was.

CM: You mentioned that you had left London because you “needed a new mythology to shield against the sense of loss and hanging dread inherent in the invasion and dissolution of my familiar London ground. Forty years learning where to walk, and a few months to lose it all.”

What was it about London that had changed? I have seen the change here in Chicago, in the last 25 years, from a gritty town—and I mean that in a good way—to what has been called the ‘Naperville-ization’ of the city. That is, the suburbanizing of it; making it sanitary, comfortable for out-of-towners to move their shopping mall experience into the city. Is that the same commodification that is happening in London?

IS: Yeah, absolutely. Total commodification. For example with the Olympics, that grand corporate project: it was being sponsored by four or five major entities such as McDonald’s and Dow Chemical and so on, and a big part of it all was this huge mall, the Westfield Supermall. You didn’t get access to the Olympic site until you went through this mall, so it became a shopping extension.

To achieve this, there was a huge series of enclosures, the dismissal of the landscape that had been there before as old parklands, orchards, allotments, and narrow-boat dwellers on the river; old factories, small businesses, warehouses, all of those things which are untidy. And they wanted to impose an overall narrative, so we ended up with a kind of war situation, where there was a whole zone that was fenced off. There were drones flying overhead; there were Gurkha regiments keeping people out of their own landscape.

This was a very strange thing to happen to the city, and it made it, to me, an uncomfortable place. I just thought, I want to go somewhere else. I want to go to a totally different place, and the place I went to, in a sense, was revisiting my own past. I had been gripped by American writers rather than English writers, and I thought it would be interesting to finally get there and look at their home places.

CM: Right, and that’s what led to your book. A review of it I saw talked about your fascination with the Transatlantic. That is, your fascination with America. Did the ordinary subject matter of the Beats, of Charles Olson turning his back on the sea and turning toward the people and places of Gloucester, Massachusetts—is that what attracted you to not only the Beats but also to America?

IS: The first draw for me was the sense of the totality; the sheer fact of the space, which Olson talks about; that it’s so big. I can go from end to end in Britain—it wouldn’t be unreasonable for me to go right up to Glasgow, say, in a day. Whereas the spaces and the distances within America are so huge that it allows you to think in a grander way.

And also the movements are more dangerous; in the mythology, you’re going into the unknown, and the country is against you. It is hard country. And at the end of it, the arrival at the Pacific is an immense moment. And then when I started to come down the Pacific Coast, in heavy, rainy, misty conditions, with these enormous forests as well as these huge rigs deforesting the state—it was altogether bigger and grander than anything that I was familiar with.

CM: You mention mythology. I don’t want to keep coming back to the same quote, but you did write that “I needed a new mythology to shield against the sense of loss and hanging dread” that you had in London. How much did you realize that what you were going to see, or what was in your mind, was a mythology?

IS: It was clearly a mythology, and the people involved [with the Beat Generation] were often the mythologizers. Kerouac quite consciously created a mythology around Lowell, the town where he grew up, and Ginsberg created a mythology of the group in the way that he’d seen happen with Paris in the 1920s, or Ezra Pound in London before that: the idea that you talk about your friends and you create a mythology of the group. And if you do that in America at that time you’ve got Life magazine, and Time coming around, and comedians are doing riffs about Beatniks, and films are getting made, and all that has made a mythology.

That mythology plays globally. Ginsberg is in Cuba, he’s in Czechoslovakia, he’s been in India, he’s everywhere. He became the global ambassador for this idea of a mythological group.

CM: You write about Charles Olson’s Gloucester: you write, “Mediterranean Catholicism, in this place I had previously imagined as puritanical and dark, is a rush of color.” What does your previously-imagined puritanical and dark image of Gloucester reveal about the way you viewed the writings of Olson, or Olson himself? Or were you misled by Olson? You were just saying how many of these people created characters of themselves…

IS: I knew from reading about Olson that he was Catholic, but I sort of imposed, I suppose, my own filter on it, and saw Gloucester as a place where the weather was harsh and the storms were beating in off the Atlantic and there’s the history of the whaling industry and swordfishing, and everything seemed quite brutal and tough.

Arriving there and seeing the bright colors in the Catholic statuary and the churches—I hadn’t had a sense of quite how strong that was. Obviously Sicilian and Portuguese communities had settled in these places and were a powerful, dominant aspect. It wasn’t all the darkness of the puritan history and the witch trials and all of those other things that were lurking somewhere deep in the back of it in my mind.

CM: And you write, when you get to Gloucester, “it’s no longer the town of Charles Olson.” It almost seems like it’s a tourist spectacle. Is that the feeling that you got?

IS: I don’t think it was—it was sort of on the edge of that. A lot of the buildings were coming down, and exactly the kind of situation you were describing in Chicago was happening there. Even the small businesses were closing down; the fish plants were going over to cat food. There was a slight feeling of economic depression and a turn to producing art for tourists. I saw a lot of bad seascapes. There were a lot of small industries trying to make it attractive to visitors rather than being what it had been: a dynamic place where there were real activities going on. So I guess it was in something of a limbo. But the history and the mythology of Olson were still pretty powerful.

CM: You write, “It is no difficult matter to identify the gap in the trees at Half Moon Beach when you’re in Gloucester: the bench where the young Olson stood listening to the two old men who he wrote about as they smoked and talked. This is the pivotal point where, feeling the immense weight of the land behind you, the overriding impulse is to turn and face the sea. The boy whose wrists were already too much for the sleeves of his tight jacket said that he was spellbound by what he heard: that male need to talk the day down. He knew their names: Lou Douglas and Frank Miles; a lazy, companionable exchange in the face of lengthening shadows as they draw on pipe or cigarette. For Charles Olson, this is where it all begins. Unnoticed, he listens.”

Is that the foundation of the Beats? Listening to workers talk about their world? Like Velázquez doing a portrait of a slave when only portraits of royals were being done? Is this bringing a class into poetry and literature and art who were dismissed—for lack of a better term—for being ‘ugly?’

IS: Yes, I think it is. I think this was a big strain in American writing that was done better than was being done in Europe. The notion of watching working men and how they behave and how they talk, and listening to stories, and sitting around in the 1940s in cafes around Times Square; university boys making contact with subcultures and junkies and male prostitutes and thieves and general city riff-raff and trying to get the language, how they speak, how they behave, the codes, and to make a record of it.

Both Kerouac and Olson emerge from working families—Kerouac’s father had a small print shop and all kinds of jobs, and liked to bet on horses and football games; Olson’s father was a postman. And they respected that very much even though they don’t go that route themselves. It’s a kind of divorce between them and this world. But they write about it. And to know how to listen is really the start of everything.

CM: You write about Gloucester; you write about Lowell; you write about Seattle; you write about Lawrence, Kansas. Gloucester and Lowell have changed a lot since the time of Charles Olson and the time of Jack Kerouac, respectively—Olson’s Gloucester and Kerouac’s Lowell. Burroughs always hated Lawrence, Kansas, so you can just put that aside for a second. But do you think that Jack Kerouac could have been the Beat writer he was in today’s Lowell? Do you think Charles Olson could have been the poet he was in today’s Gloucester?

IS: I think Olson certainly could. In his case, it wasn’t the place where he’d grown up. He grew up in Worcester. He used to go to Gloucester for his summer holidays, and it was an important place to him. And obviously he moved; he taught at Harvard, and he was in Washington working for the Democrats during the war era, and he spent time in Mexico. He moved all around.

But it was really when he got back to the childhood place of Gloucester that he recognized this was going to be a major project of his life, to actually understand this small place and see its significance. Archiving local characters and myths, looking at statistics and absorbing all this material in what he called ‘open field poetics’ and then, at the end of it, to wrestle it back into a kind of Homeric voyage, a mythology of its own that connected up with the verities of the cosmos, the oceans, the stars, everything. It’s a terrific and huge project based on a small place.

Whereas Kerouac was embedded deeply in Lowell; he grew up there and wrote about it in numbers of books—obviously he went off on these journeys, but the journeys were a sort of desperate, reckless, neurotic thing that were never satisfying. They weren’t going to anywhere. They were really about seeing if the mythology of the mass of America lived up to what he thought it should be from his own reading. And he didn’t end up living in Lowell. He moved down to Florida with his mother, and it was kind of a nasty, bitter end.

Whereas Burroughs, although he grew up in St. Louis, really was a citizen of nowhere. He just perched. He went to these places he described as “interzones.” He liked living in Tangiers, in North Africa, when it didn’t really belong to any particular dominant political force; it was between cultures, and it allowed an outlaw lifestyle. And then of course he moves to a small Beat hotel in Paris, and then on to London and an almost secret life, and then his bunker in New York and finally Lawrence.

He keeps endlessly moving, and endlessly engaging with this compulsion to be a writer, which he said started when he shot his wife in Mexico City and wasn’t finished until he went through a Native American sweat lodge ceremony that teased out the ugly spirit that had been possessing him all this time, and he stopped writing and just started painting and recording dreams and so on. At the very end he wasn’t writing anymore.

CM: You quote William Burroughs saying something that would seem to be the antithesis of reporting on the ordinary, as so many Beats did. Burroughs says, “the further West you go, the worse it gets. I was born in St. Louis, and so was T.S. Eliot. Place is of no importance. I’ve spent my life looking for a better vintage of boredom. A third of my material comes from dreams, from no place at all.”

I’ve always been taken by Burroughs, more than the other Beats. Is that what makes his work unique within the Beats? The dreamlike state of his writing, the anti-Beat reporting of the strange, not the ordinary, the sense of a lack of psychogeography in his work?

IS: I think that’s absolutely right. I think he disassociated himself from any notion that he was part of the Beats. They had been friends of his at various times, and he collaborated with them in various ways, had a relationship with Ginsberg, but he was never really that kind of writer. As you say.

For a start, he was very highly educated. He’d been through Harvard, he’d done post-graduate work, he’d gone to university studying medicine in Vienna. He was the source, he was really the scholar to start with, and he set himself up against the big writers rather than just mythologizing his own life, which was extraordinary.

I think he had a very modern sensibility: that you don’t have to have narrative construction. That all breaks down. He keeps calling the word a ‘virus.’ If you look at what happened to him, it was a battle with this virus. He was very interested in people who had all kinds of strange out-of-body experiences or claimed to have been taken up into spacecraft by aliens, anything like that he was a sucker for, and he got interested in Scientology at one point.

But all of this doesn’t really matter; it all goes into the sheer craft of the writing, which was an absolute for him, not anything to do with lifestyle. The fact that he keeps a record of so many years of addiction—and stayed alive—seems extraordinary for such a long life and such an endlessly embattled one.

CM: So despite Burroughs saying “place is of no importance” –

IS: It obviously was.

CM: How much do you think place informed his work?

IS: Place was important to him in the sense of sets. He thought of places as sets, interchangeable sets. He kind of auditioned places for where the material would be good for a book, slightly like what Graham Greene had done in his era. When ennui was on him, when the dark moods were on him, he would take his lawless rogue journeys through Mexico, or he’d go off to West Africa; Burroughs made a complete career of looking for the right set. And he found a great set in Tangiers; he found another set in London. He accessed different materials and different styles of life in these places.

But the place really wasn’t of any importance other than it was giving him the background to write about; it was interesting in that way. And that’s very different, I think, to the others. Ginsburg and Gary Snyder went on spiritual quests; going to places was changing states of consciousness, looking for forms of enlightenment and importing them back into America. Burroughs is not interested in that at all. He’s just interested in finding new characters for his fiction, while recognizing that—because I think he thinks they channel him—they’re looking for him. He’s much more like a magician.

CM: I want to read the passage you mentioned earlier about his meeting with a Sioux medicine man. You write, “a sweatlodge ceremony with a Sioux medicine man revealed and then exorcized the ugly spirit that had oppressed Burroughs for so many years, a spirit in the form of a winged Vietnam War helmet, a spirit representing the karma of American materialism and invasion guilt, a spirit smelling of chicken fried steak and napalm. This spirit was the curse laid down when Burroughs shot and killed Joan Vollmer in Mexico City in 1951, a curse that could only be ameliorated by dedicating his life to writing, taking the dictation of the old ones, and now the job was done.”

So for Burroughs, was language the virus or was America the virus?

IS: Language was the virus, but it was a language that was cooked up in America by the black magic, the occult magic of capitalism, the military industrial state as he saw it—which he recognized with a considerable relish.

He anticipated the surveillance society; he anticipated water-boarding. He writes a lot about the kind of acts of terrorism that have become commonplace. He anticipates all of that in his writing, from what he sees. And he keeps talking about the “ugly American,” as if the American somehow goes into the world as a force of darkness. And he’s going to be the person who keeps a record of that.

Until, obviously, this moment at the end when the shamanic ceremony produces a visible emanation, this helmet which just flies out of him. It’s strange, because even though that’s an ugly thing it means that he doesn’t have to write anymore. The writing was a burden to him as much as it is a delight or an enlightenment for the rest of us.

CM: You mention the menagerie of animals in Burroughs’s home: the wounded rats and feral cats; he saved raccoons, possums, he feeds outside animals. You write, “all of these creatures, like Lawrence, Kansas itself, like America, is dying.” How did you see America dying on your visit?

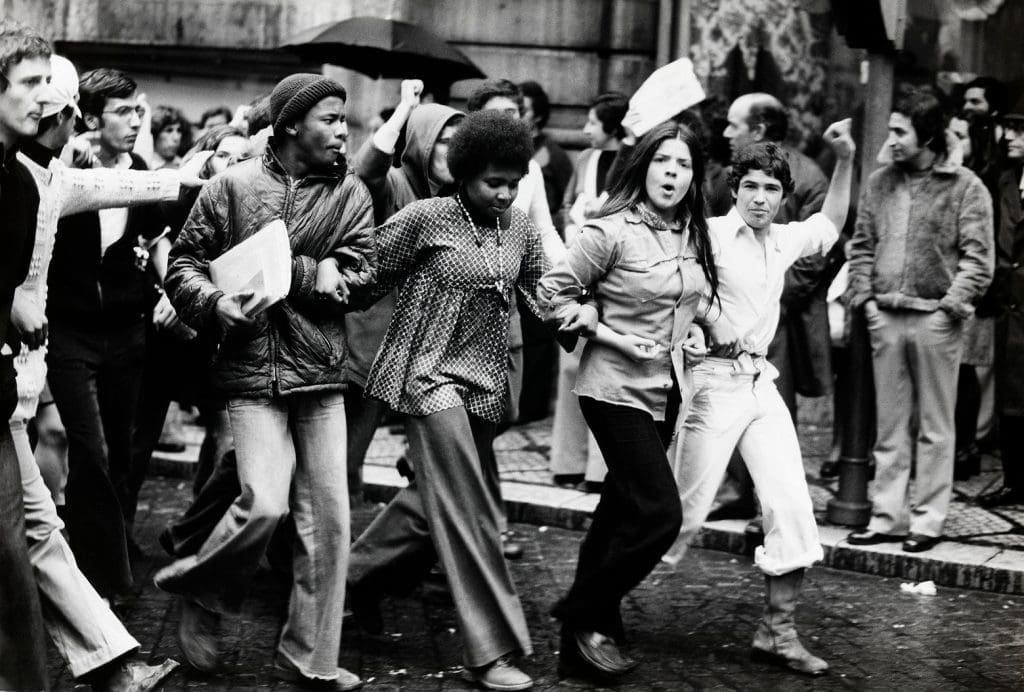

IS: I just felt a certain energy, something I suppose I’m mythologizing for myself: this world where all information is available instantly, everything is becoming part of a corporate entity, everything can be explained in certain kind of bland language, there is a uniformity—and a sense of economic desperation as well. A lot of people were taking to the protests on the streets at that time and camping out with the V for Vendetta masks and all of that.

It was as if this great dream had not worked. The thing we’d all bought into—not just America, but we’d copied it [in Britain]—wasn’t working. It was failing, failing people badly, and leaving terrible damage in its wake in cities like Detroit, which looked more or less like warzones. It looked as if the whole thing was dying on its feet.

CM: One last question for you, Iain. You write of the “futility of American tourism, this incontinent expenditure of words.” Why did you find your travels here futile? After all, didn’t you get to engage with the heroes of your youth, or whatever legacy they have left behind?

IS: I didn’t really find it futile, that was a sort of a fictional gesture at the end. Because this book is not documentation, it’s creating a mythology. A lot of it, if it’s not entirely fictional, is adapted to fit within a structure. And at the end of it, I was getting some flak from some of the people I had written about, and I thought, well, okay, fine, I don’t know anything. So I wrote that passage at the end to say, well, okay, I don’t know. I’ve done this journey, and it was not enough. I’d only been there for such a short time, what right do I have to talk about anything?

But on the other hand I think I have every right to talk about it; I’ve been engaged with this material all my life, and every day that I breathe in the city of London, I’m still faced with the energies that are coming from the same places. We’re all part of exactly the same structure now. So where I am is America as much as where you are.

CM: I really appreciate you being on the show with us this morning, Iain. It’s an honor.

IS: It’s been a pleasure, an absolute pleasure. Thank you.

Featured Image: Either a set from Blade Runner or the London Shard, photographed at its ‘unveiling.’ Source: Mosey Burns Photography