As hard as it is to look on the bright side at the moment, we must acknowledge intriguing connections currently being made between disparate and distant movements. Our task now is to make these confluences of action and intent—this growing solidarity across ideological and geographical chasms—much more concrete, combative, and contagious.

By Antidote’s Ed Sutton

By nearly any account, it has been a devastating summer, and a tough year all around.

On the international radical ‘Left’ (whatever, indeed, that is), following several years of what seemed like building momentum worldwide, we began 2014 watching a new batch of popular revolts come undone in a rather new way. To blame this time were not merely the expected forces of reaction within institutional power structures, but also populist social currents, leaning hard into fascism, within these revolts themselves. We were confronted—notably, but not for the first time—with reactionary movements adopting traditionally leftwing tactics, leaving many dismayed and wondering how on earth to respond.

The Antidote Writer’s Collective attempted, in the winter and spring, to untangle these and other deeply confounding threads, bringing in revolutionary voices concerning Ukraine, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Syria, Palestine, Venezuela, Brazil, the United States, and many other fields of struggle.

Then summer hit, and the mounting shocks and slaughters shattered any rational comprehension. Increasingly, in nearly every corner of Left discourse, talk shifted from Debord to deboarding; depression set in. I don’t mean that euphemistically, and I don’t exclude myself.

Antidote was not the only political site of its kind to be stunned into silence as the IOF began to level Gaza, to the literal cheers of a new generation of outspoken Israeli fascists (resembling their European counterparts ever more blatantly); as the Islamic State rolled over one Shi’a city after another in Iraq (to the world’s astonishment despite the IS’s previous advances in Syria); as mass graves and detention warehouses full of Central American refugees were ‘discovered’ all along the U.S.-Mexico border; as long-simmering racial tensions in the United States finally boiled over after yet another police murder of an unarmed black youth, this time in deeply segregated Ferguson, Missouri; and as, through all this, Bashar al-Assad took the opportunity of the world’s diverted attention to further consolidate recent military gains in Syria and brought the death toll in that war to 200,000, with over 3 million now displaced.

Meanwhile, global neoliberal power shores up its terrifying fortifications, effectively unchallenged, and climate change continues apace. And there’s plenty I haven’t mentioned.

I say ‘we,’ and I speak of fields of struggle; this implies that the international Left is somehow engaged with any of these events in some coherent way. From afar, though, it appears that in some of these cases the struggle has rather devolved into fascists versus fascists. And in others, the power dynamic between aggressor and oppressed is so bound up in deranged historical and local wretchedness that (often clueless) “solidarity” from outside is unhelpful, or unwelcome.

How do we intervene in such conflicts? Is it even meaningful to do so?

These are questions with which we have always been concerned on Antidote, and previous articles we have posted provide some alternately tentative and forceful answers. And as is the case in any network of writers and agitators such as ours, we have also been wrangling with these questions among comrades—and opponents—behind the scenes. In the midst of such devastation and despair (though at the same time isolated from it; we are, after all, based in Switzerland), just the very fact that the discourse continues should be some comfort.

That is, of course, weak sauce. Stronger stuff, however, has emerged from these discussions. In lieu of setting out some grand strategy or launching into some vapid peptalk at this least opportune of times, I would like simply to share some of the ‘stronger stuff’ with you, that it may become grist for further mills.

Among the optimistic observations I heard over this Summer of Sadness was one that is perhaps often made at such times: that accompanying all of this horror, and plausibly resulting from it, has been a generalized radicalization, steady and tangible. To borrow the words of an AWC comrade: I have never felt so much revolutionary energy, from so many people, as right now.

Giving content to this generalized radicalization has been the learning curve exacted by any ‘game-changing’ event—a title appropriate for any one of this summer’s disasters, let alone all of them at once. I think it is also important to bear in mind that this is a radicalization within a radicalization, occurring in the midst of a crisis—ongoing for at least seven years now—which another comrade recently described to me as a time when common sense already no longer holds.

Therefore the events of this summer have caused many ‘fringe’ criticisms of existing strategies, tactics, and proposed solutions to begin gaining broader traction. From mainstream policy ideas such as the Two State Solution in Israel to milquetoast activist approaches such as appeasement of—and collaboration with—authorities by the so-called Black leadership in the United States, more and more previously accepted frameworks are being called into question, or simply revealing themselves as absurd. Other avenues of thought and action are being considered more seriously by more people, whether that means starting to ask what a One State or No State Solution would look like in Palestine or defending rioting as a legitimate response to endemic state violence.

Further, as people, some with the indomitable energy of the newly radicalized and others with the impatient frustration of years of being ignored and dismissed, begin finally (or again) to raise their voices, they are also finding that their outcry has resonance in unexpected quarters. The boundaries of struggle—and between struggles—are being exploded. This has been perhaps the most frequent topic in the discussions I have been having. It is where I see the most hope and potential for continued organizing in the wake of such catastrophe, and it is the reason for this essay’s title.

First Destroy the Dams

In recent weeks much has been written, both adoring and disparaging, about the connections being made, both real and conceptual, between Palestinians in Gaza and Blacks in Ferguson. This axis certainly informs the argument I am so slowly getting around to making: that encouraging, exploring, and expanding these sorts of connections is an essential part of our work. But I am far too conscious of my privileged remove from both struggles to wade too deeply into that conversation here.

Instead I’d like to touch briefly on an issue that has, like so many others this summer, taken a back seat to more spectacular ones despite being no less immediate: the ongoing refugee crisis. Which one? In a way, that is precisely my point. There really is only one; all of them. Gaza and Ferguson are not the only struggles between which we should be drawing connections.

I’ve been struck by the countless parallels between the U.S. refugee crisis (though that’s generally not what it’s being called there) and the refugee crisis in Fortress Europe, which has been going on long enough now to have faded from mainstream discourse even before an ‘escalation of hostilities’ in Ukraine, Palestine, or Iraq could supplant it.

All of the horrors we’ve been hearing of in the U.S.—racist militias, militarization of the border, pushbacks and deaths, detention warehouses, state-conducted pogroms in urban centers, forcible deportations—have been going on in Greece for several years, at minimum since the confluence of the Eurocrisis and the nearby Arab Spring increased both the flow of migrants and the brutality with which state and society meets them. As we have reported on Antidote recently, the very same things have been happening in Bulgaria as well. Of course the phenomenon is not limited to just those two countries.

A radical activist response, involving a confluence of its own, is taking shape across the continent. For example, in France and Germany recently (most notably Calais, Hamburg, and Berlin), political squatters and refugees have united in struggle in headline-grabbing ways—and refugees have independently taken to occupation as both a militant tactic and as a solution to their desperate physical circumstances.

In Switzerland there are Autonomous Schools in several cities, founded jointly by anarchists and refugees to provide resources that the state is either too incompetent or too racist to provide, such as language courses, legal advocacy, and integration help.

And in Greece, as we have also detailed in these pages, the long-established radical infrastructure of militant squatters and their allies has also stepped up in cities across the country, offering to all comers hot meals, medical care, and even defense from racist assault. This self-organized suspension system á-la Rebecca Solnit’s Paradise Built in Hell, though woefully insufficient, has been an immeasurable material help, but moreover, by its very existence it poses a direct, poignant challenge to a hostile, expulsory system that ruins—and takes—the lives of migrants and Europeans alike.

As it happens, of course, this is the same system that ruins and takes lives in the United States. Isn’t a similar activist confluence—representing, then, a transatlantic confluence—possible there? There have been high-profile glimmers of increasing militancy among both undocumented migrants and property resisters in the U.S. It would be encouraging to see them recognize commonalities with each other and with struggles in other contexts, take international cues of the kind being exchanged between Gaza and Ferguson, and begin to work together to adapt both their analyses and their actions to transcend their compartmentalized campaigns.

This could take many forms. “Move in!” has been a favorite refrain of mine in previous writing, and I enjoy picturing housing justice activists and hordes of the homeless banding together with refugees, breaking into vacant homes ‘owned’ by no one but distant banks, creating safe spaces and new kinds of cooperative communities in them, and defending them tooth and nail from the inevitable repressive flailings of a system slowly realizing that decades of planned obsolescence have really only made it obsolete.

That’s just my idle daydreaming, of course. The people actively engaged in these sorts of struggles could be far more imaginative, especially if they bear in mind that common sense no longer holds in this crisis. Many surely do; it is all too obvious that the ‘common sense’ of private property in its present form requires violently kicking people out of a country dotted with millions of empty houses. Equally absurd is the ‘common sense’ that insists that the housing justice and refugee struggles are distinct from one another.

Recognizing their commonalities involves recognizing that, in the U.S. as in Europe, the refugee crisis and the housing crisis emerge essentially from the same rot in the logic of capitalism (to paraphrase journalist and podcast host John Knefel). For that matter, so do police violence and militarism, the resurgence of fascism, and so many other—arguably all—of the horrifying manifestations of structural injustice we are fighting in so many seemingly isolated theaters.

This brings us to one last topic that has been central to much of the AWC’s muted discourse this summer, one whose rough outlines can be seen in an essay by our comrade Deckard of the Permanent Crisis blog which we shared earlier this year. The title says it all: What Form Should Our Movement Take?

I have understood this question for some time now as having two kinds of answers: ones that propose to identify a project of explicit primacy which we should all be rallying around, and ones that involve fostering a multivalent struggle tolerant of high degrees of diversity and dislocation. This is a fundamental, perennial conflict.

Here, however, I have the pleasure of continuing my tradition of using these pages to expose my own misapprehensions. These two schemes are neither necessarily dissonant nor mutually exclusive. The multivalent struggle we in any case already have will begin to resemble a unified, primary, and truly revolutionary project the more connections we make—and make concrete—between us, on the basis of our still largely unacknowledged common cause: ending capitalism.

There is a word for this, of course: solidarity. Exploring this word’s meaning—or its lack thereof due to decades of insincere, superficial misuse—is well beyond the scope of this already rambling essay. The definition I will close with is far simpler, that of my title word confluence: a flowing together. I like this word because of its air of natural inevitability and power; it is, after all, used to describe the meeting of rivers.

Many of the dams preventing potentially powerful political confluences, we built ourselves. As we recover and regroup after The Worst Summer Ever, let us begin by destroying them first.

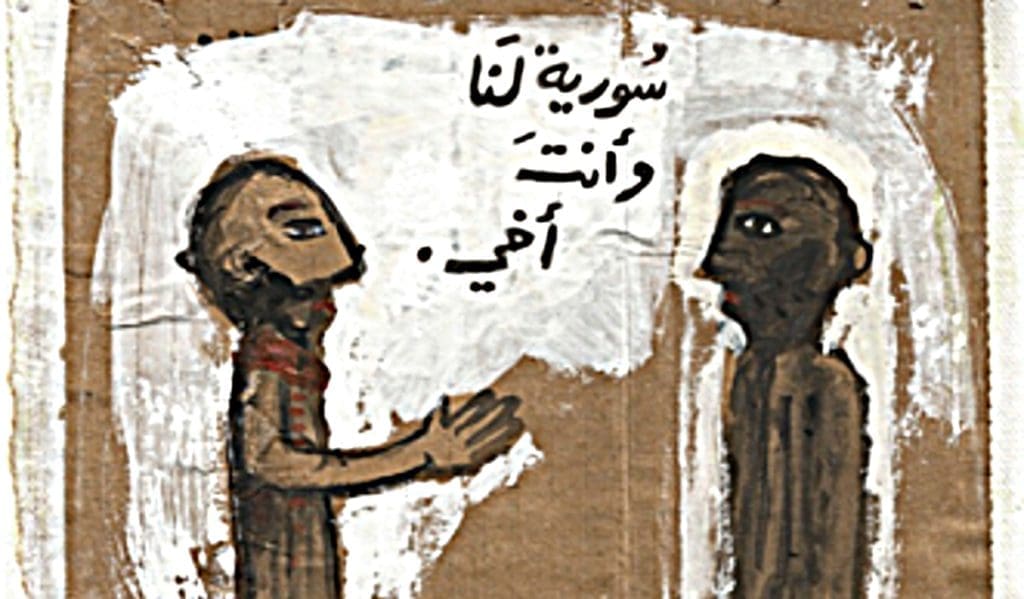

Featured image source: the amazing Berlin Refugee Strike blog