Transcribed from the 2 August 2014 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“We’re going to see the rise of a mass detention and deportation system [for immigrants] that will very much rival mass incarceration, and could actually grow as mass incarceration shrinks.”

Chuck Mertz: Live from Berkeley, Jonathan Simon is author of Mass Incarceration on Trial: A Remarkable Court Decision and the Future of Prisons in America. Good morning, Jonathan.

Jonathan Simon: Morning, Chuck.

CM: You write, “Like a biblical flood, the age of mass incarceration is finally ebbing. After forty years, not forty days, a once-unstoppable tide of harsh sentencing laws, aggressive prosecution policies, and diminished opportunities for parole seems to be subsiding.”

Forty years is two whole generations of human beings. What do you think the cultural legacy of that mass incarceration is, or will be?

JS: That’s the reason I began with that image. These are biblical generations. And we know that biblical generations transform cultures, right? That’s why the Israelites needed to spend forty years out there in the desert: to get to a new place, at least metaphorically speaking.

The place that we’ve been transported to, unfortunately, could be a devastating place. The damage to our communities from this forty-year period is being assessed by sociologists and others who are now finally paying attention to it. But it clearly has the magnitude of any other social disaster we’ve ever had—the Great Depression, the mass-internments of the mid-20th century.

One of the reasons I wrote this book is that it’s going to take a mobilized citizenry—as well as legal actors like judges and lawyers—to get involved, to really change that.

Another reason forty years is important is that a lot of the social and cultural conditions that animated mass incarceration have also faded. If you’re a baby boomer, you came of age in the seventies—if not a little bit earlier—when the crime rate was going through the roof; when the social science we had at the time was telling us that we really didn’t have any tools to deal with crime; and when courts were in the business of cleaning up prisons all over the country, and it looked like they were becoming more humane. A lot of those assumptions helped to fuel mass incarceration, and by now they have all run their cultural course.

CM: One of my very first memories is of seeing the tanks and helicopters coming into Detroit for the riots. I was raised during that time, and it was a very frightening time—especially as a child, when your parents are frightened of what’s going on around you. You get incredibly frightened.

But it seems like mass incarceration “worked”—right? Why couldn’t somebody who is pro-mass-incarceration say, “Look, it worked. Crime rates have dropped since the seventies.”

JS: One of the reasons I’ve been a pessimist for most of my professional career is that it looked like a pretty formidable—maybe unbeatable—system. It has powerful economic logics that keep it going, that have been described by a lot of folks. It has, as you point out, a deep internal logic: if keeping dangerous people locked up is keeping us safe, then any time any prisoner gets out, all of us must be at least a little bit less safe. And after all, crime has gone down in the last decade or so, which is an important and positive thing.

I really didn’t think we were going to beat this thing, at least not in my lifetime. The reason this case has made me so optimistic, in a way, is that it exposes what I think of as the soft white underbelly of mass incarceration—that is, the fact that in order to create mass incarceration we had to confine a huge population of people, a large portion of whom are chronically ill, both physically and mentally.

And what we now know—what this case has highlighted—is that incarceration is a cooker of chronic illness. It enhances it, furthers it, progresses it, makes it harder to fight later, increases the cost and the personal suffering. I think that has actually made mass incarceration an equivalent to our “zombie banks:” it’s unsustainable in an economic sense—but more importantly it’s unsustainable in a moral, humane sense.

CM: We’ll get back to the mental and other healthcare issues in a couple seconds, but I wanted to ask you some other general questions.

You write that “today, the number of people imprisoned in America remains at or near historic highs, nearly four times the average incarceration rate for the first three quarters of the 20th century. But the quantitative trend is mostly downward.”

What has driven the decline of mass incarceration? Is it just a downturn in government spending? Is it just that prisons are getting too expensive, looking at the bottom line?

JS: There was a certain amount of that during this past decade of Great Recession, in which state governments in particular have been really starved and have had to retreat a little bit on the sacred value of expanding the prison population. My concern is that that won’t get us very far. We’ve come down a few percentage points from the peak, and we’ve got a three or four year trend going here, but in California we’re running budget surpluses again. Which means if a new governor were to come in or a tide were to turn and people were to panic more about crime, you could see those engines fired up again.

That’s the reason it’s so important to see this shift to a question of the immorality and basic indecency of mass incarceration. I am perfectly capable of being very pessimistic and cynical about American politics, but I think that Americans have a deep intuition about decency. We saw it in the Abu Ghraib moment about a decade ago, when Americans who were fairly supportive of the War on Terror said, “wait a second, that wasn’t what we had in mind,” when they saw those images of degraded bodies.

If we leave this to a purely financial, economic calculus, we might end up with an incarceration rate that’s maybe a third less than at our peak, but will still be two thirds more than it had been for the whole 20th century. It’ll still be a predominantly black and Latino population. It’ll be legitimized because they’ll be there for more serious or violent crimes rather than drug offenses. We’ll end up with what I call “mass incarceration light” at the end of the next decade.

One way to put it is 2014 is to mass incarceration what 1964 was to segregation: the year that it became totally discredited but also ended up becoming a norm for American society. We’re still a very, very segregated society.

CM: One fear has been that the private prison industry would drive the market for prisoners, and thus the privatization of incarceration would lead to a continuing increase in prisoners. Why isn’t that happening? Why isn’t privatization continually driving more and more prisoners into the prison system? Isn’t that how prison companies make money?

JS: In a lot of the big states that have driven mass incarceration, including California, the private industry never got as much of a foothold as it has in some other states. Here, strong unions in the correctional sector have kept it pretty much a public monopoly—until the “state of emergency” allowed the governor to put some prisoners in private prisons.

The private sector is doing pretty well right now with the immigration crisis. They’re less concerned with having to animate new laws to put more people in prison because immigrants look like a better target for private corporations. They’re younger, they’re healthier, they don’t have to be held as long as ‘traditional’ prisoners.

So I think—and this frightens me—that we’re going to see the rise of a mass detention and deportation system that will very much rival mass incarceration, and could actually grow as mass incarceration shrinks.

CM: That is frightening as hell.

You write that “states have begun to modify some of the most extreme sentencing laws (including New York’s infamous Rockefeller drug laws, which created life sentences for first-time possession of modest quantities of drugs for sale), and once-impossible alternatives to routine imprisonment for many drug and property crimes are beginning to take place at the state level.”

How much would the end of the war on pot cut the prison population? And if we did actually end the War on Drugs, do you think that the police or law enforcement would just try to find another way in which they can control the populations? Because as Alice Goffman pointed out on our show, the War on Drugs is often used by law enforcement in minority neighborhoods as a way to control the population.

JS: I’m worried about that, on exactly the grounds you’re saying, though I think ending the War on Drugs is imperative for a whole variety of reasons.

We’re already seeing a number of things going on. One is that law enforcement is segueing away from focusing on drugs to a variety of other “quality of life” crimes. We can already see the rhetoric out there on “pimping.” The claim is that young men of color are switching from selling drugs to selling women. It’s being turned into an abstract monstrosity, the way crack was. Pimping is the new crack, basically.

[Please see our transcript of Mertz’s interview with author Melissa Gira Grant for a further evaluation of this claim by law enforcement and others about “pimping.” –ed.]

If you look at the latest federal reports on the national prison population, they’re trumpeting the fact that there’s a shift from drugs—which peaked in the late nineties and early 2000s in terms of their impact on the prison population—to “violent crime.”

Again, imprisoning people for violent crime has a lot of legitimacy in America. It hasn’t really been touched by critiques of mass incarceration. That worries me, because violent crime can incorporate lots of different behaviors, including non-injuring behavior, and also because many people feel that it justifies lengthy prison sentences, when in fact people’s real inclination to violent behavior is often a fairly short span of their lives.

Again, that pushes me back to the humanity problem. We could end up with prisons that look more legitimate because they contain offenders that are called “violent” or “serious” or “lifetime” offenders, but they’re going to be just as inhumane—and they’re going to be just as racist—as the ones we have now.

“This inhumanity has come from creating a system of imprisonment that is incapable of treating people as individuals. And that’s a little bit weird, because in the history of prisons that was the idea—that the cell would reflect the individual.”

CM: Is the problem simply overcrowding? That’s the way that it’s always depicted on the news. They don’t say the problem is mass incarceration. But they’re very concerned about the conditions within “overcrowded” prisons. Why couldn’t we keep up with the demand? Why couldn’t we just continue building prisons so we wouldn’t have overcrowding? Would not having overcrowding end all of the problems of mass incarceration?

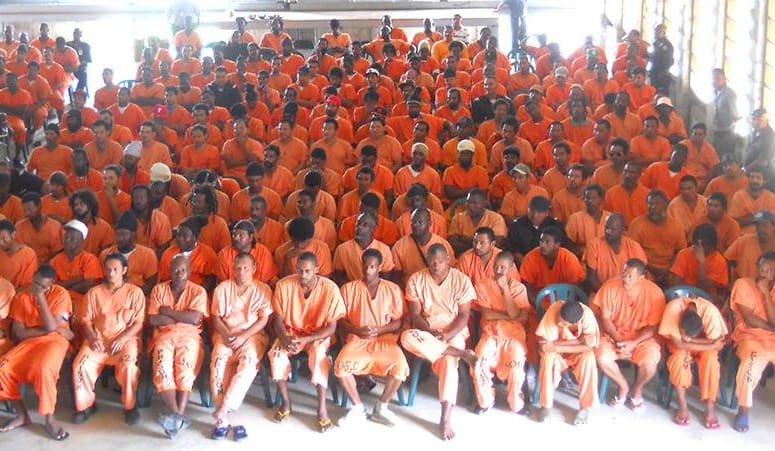

JS: That’s a great point. California had two decades of what I call chronic hyper-overcrowding (I don’t think simply “overcrowding” is a good enough term to describe living in a prison at, say, 300% capacity).

Some of it’s economic, but much more integral to the very idea of mass incarceration is this: if the goal is to reduce crime by essentially excluding from the community as large a proportion as possible of groups you’ve defined as “high-risk” (drug users, people in inner city communities, etc.), and you’re not trying to rehabilitate them, you’re not really doing anything with them, then the laws you’re going to create for that system that fast-track people into prison are automatically going to lack tools to individually examine, recognize, and treat any medical and mental problems that they have.

Even though you might intend to keep up with your prison population, it’s very hard to do. The laws put in place to fill the prisons don’t produce new prisons. They produce new prisoners. If you want to produce new prisons, you’ve got to put together coalitions in the assembly; you’ve got to put together funding or bond packages on the market and things of that nature that are much more complicated.

So there is a structural aspect of mass incarceration that leads to overcrowding. And it’s not just in California. About a quarter of states right now show hyper levels of overcrowding; that is, over 150%. Anybody who ran prisons up until about 1970 would have said you never even want to get near 100% capacity. You can barely operate a prison at 100%. And most of our prisons are at or above that.

At the end of the day, this inhumanity has come from creating a system of imprisonment that is incapable of treating people as individuals. And that’s a little bit weird, because in the history of prisons that was sort of the idea—that the cell would reflect the individual. That it wouldn’t just be a mass of people in jails the way it was in the 18th century. That led to typhus and other epidemics that actually killed a lot more people in the community than they did in the criminal justice system.

Our commitment to that idea broke down completely during mass incarceration. We lost the capacity to know or act on prisoners as individuals. When you do that, inhumanity follows.

Especially when you assemble a prison population that has so many vulnerable people in it. Again, we couldn’t get mass incarceration if we were only going after professional criminals, as we were—more or less—in the fifties. We’d have a much fitter, smaller prison population. When we go after drug users, when we go after people caught up in cycles of criminalization and incarceration who are imprisoned for many years and keep coming back, we’re taking on a population with a huge burden of illnesses.

One of the things that the court helped to teach us is that you don’t need to tie somebody down and put thumbscrews to them to torture them. You can also, say, isolate them with diabetes and not get them the right kind of medicine.

CM: Despite new prisons being built throughout the 1980s and 1990s, you write that “a variety of factors created conditions in the new prisons far worse than anyone on the outside imagined—except, of course, members of prisoners’ and prison officers’ families, prisoners’ rights lawyers and the formerly incarcerated. First, rehabilitation was out of fashion as a justification for imprisonment, and while all too many assumed a rehabilitative approach would continue to inform penal practice, administrators of the new prisons showed a crass disregard not just for rehabilitative treatment, but for humane treatment.”

So prisons have gotten worse, not better. What changed in the eighties when people started becoming more crass, more inhumane? Did our culture, our politics, or simply prison culture from the top-down—from warden to prisoner—simply give up on rehabilitation?

JS: It’s the assumption that prisons had gotten better, beginning in the seventies, and that they were more humane, that helped Americans—the elites and also ordinary citizens—make peace with the idea that we needed to keep a huge portion of the population in these prisons.

If we look, again, at the boomer generation (which has had so much political influence), we went through a slow-motion 9/11 around homicide and violent crime in the seventies. And that produced a “hunker-down” mentality, like we also saw after 9/11, that allowed people to say, “okay, unleash the police, do what needs to be done to put the lid back on violent crime in America—and oh, good, those are humane prisons.” That allowed us to go forward.

What happened is that states like California, which had actually been progressive and had prison systems based on ambitious psychologically-oriented programming—when they got rid of that, they didn’t have anything to fall back on. Instead, they got in the business of running warehouses.

It’s hard to say so, but this put California in the position of actually producing prison conditions that may have been worse than some southern prisons, which had always known how to run coercive, degrading prisons—but with some kind of floor to them. In California the floor fell out.

And I don’t think we’re alone. There are a lot of Midwestern and other states in the border regions where conditions are just despicable. There just aren’t enough lawyers, yet, to bring it to light.

“You don’t need to tie somebody down and put thumbscrews to them to torture them. You can also isolate them with diabetes and not get them the right kind of medicine.”

CM: You write, “California built prisons heedless of the humanity of those it planned to incarcerate, recklessly accumulated people with chronic illness in those prisons, and committed itself to an extreme penal philosophy that left the state unable to address the inevitable suffering and death. The results were atrocious enough to move even a Supreme Court long tolerant of mass incarceration. In the words of Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion, ‘just as a prisoner may starve if not fed, he or she may suffer if not provided adequate medical care. A prison depriving prisoners of basic sustenance, including adequate medical care, is incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society.’”

There’s the famous Dostoevsky quote: “the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” At its height, what did mass incarceration say to you about the degree of U.S. civilization? And can we improve our civilization by improving services for criminals who are serving prison terms?

JS: The Supreme Court’s invocation of dignity could be a turning point, not just for legal elites who have been complicit in mass incarceration, but for the general public, which I think has an intuitive sense that we want our institutions to be decent. When I’ve talked to public audiences here in California, which remains a place in great fear of crime, I find that when I talk about these questions of humanity, people get it. They get it that when punishment is degrading, it doesn’t do anything for the victim; it dishonors the victim. And it produces responses that lead to more law-breaking.

And we haven’t talked much about correctional officers, but it degrades them too. They may be making better wages than they were before, but they’re being degraded on a very high level. But there’s a cultural rise of concern with dignity going on in our society, and I think if this case can help connect prisoners to that, it really could be a turning point in our devolution to these really despicable, indecent prisons.

CM: To what degree is mass incarceration a vulnerability when it comes to our country’s foreign policy, in the way that other countries view the United States?

JS: Mass incarceration has become a symbol not only for the fact that we’re not what we were forty years ago in terms of a beacon of human rights for other countries, but it’s also an example of our inability to overcome our political pathologies.

That is, it’s clear that it’s weakening our society, it’s weakening our economy, it’s making us more rigid and tied in with high future costs like these chronic healthcare problems. And around the world, people can see that we’re not solving our big problems, and it’s very hard for them to take seriously our pronouncements about how they should live or change their political systems.

CM: You write, “Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion departed substantially from the presumption of dangerousness commonly projected onto all felons by agreeing with the trial court that California could divert many felons currently being sent to prison without endangering public safety. The alarming common sense about felons, however, was vividly represented by Justice Samuel Alito’s dissent, in which he asserted that the majority ruling would result in ‘the premature release of approximately 46,000 criminals, the equivalent of three army divisions.’”

Does this all come down to conservatives exaggerating the danger of criminals, and liberals underestimating the same dangerous criminals? Is that the key debate on prisons? The “true” dangerousness of prisoners?

JS: Well, I think it is an important debate, but I don’t think it divides liberals and conservatives, because both liberals and conservatives fall into the “common sense” that America has an extraordinarily high crime rate because we have an extraordinarily high level of very dangerous people. Today, liberals and conservatives of a certain—younger—generation are falling away from that. It’s us boomers who you really can’t trust on this point, whether we’re liberals or conservatives.

Most of our models that built mass incarceration assume that criminals—or people who commit crimes, to be more precise—don’t change. That they’re like sharks: as long as they’re in the ocean, they’re going to be consuming other fish; as long as they’re free in the community, they’re going to be committing crimes. We now know that that was just a bizarre and absurd portrait that previous criminology would not have supported and which much better research today shows is just wrong.

People have great variance in their own life in terms of their offending behavior, and locking people up for decades is an incredibly stupid, illiberal—and unconservative—way to try to fight crime.

CM: One last question for you, Jonathan, and it’s our Question from Hell, the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience might hate your response. Is mass incarceration collective punishment against the American people for allowing the sixties to happen?

JS: It’s not ‘punishment’ in the sense of being willful and intentional, but it very much remains a response to the transformations in American society during that decade that we’re still on the way to fully integrating and accepting. Some cultural stuff is very positively moving in that direction, as we see with the transformation of drug issues and same-sex issues, etcetera.

But the other side of that decade was that our cities got really messed up. You grew up in Detroit; you saw that firsthand with the freeways and the “urban renewal” that pretty much destroyed the urban fabric. We need to fix that, that part of the sixties, if we want to get back to cities that can be governed in democratic and not so coercive ways.

CM: Who knew that suburbanites re-entering the city would ruin the city?

JS: Well, giving them their own specialized high-speed tubes to get into the city turned much of our urban landscape into what we now know is an incredibly criminogenic environment.

CM: Jonathan, I really appreciate you being on the show with us this morning. Thank you very much.

JS: Thanks for having me, Chuck.