Transcribed from This is Hell! Radio’s 15 November 2014 episode and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

“So I’m standing there on the bridge in Sarajevo where the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand happened. It’s June 28th, 2014—the exact 100th anniversary of the assassination—and ISIS is live-tweeting their invasion from Syria into Iraq. Under the hashtag #SykesPicotOver.”

Chuck Mertz: This week we honor the anniversary of World War I ending on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. It was supposed to be the “war to end all wars.” Instead, the peace that ended hostilities wound up being the peace to end all peace. Especially in the Middle East.

To provide the historical context that is always ignored in the news, Charles M. Sennott is the cofounder of Global Post. Good morning, Charlie.

Charles Sennott: Good morning. How are you?

CM: Good!

Charlie also heads up the Ground Truth Project, a foundation-supported initiative that is dedicated to training the next generation of foreign correspondents in the digital age, and producing in-depth special reports for Global Post. This one is called The Eleventh Hour, and it is about the legacy, the impact, the effects of the 1916 Sykes-Picot treaty during World War I.

I’m always struck by the different ways in which November 11th is recognized around the world. That date originally honored Armistice Day, celebrating the armistice signed in Germany ending World War I. Here in the States we changed the name to Veterans’ Day, to honor all who have served in the U.S. armed forces in all wars. In the Commonwealth they honor Remembrance Day, or Poppy Day, which memorializes members of the armed forces who have died in the line of duty.

What do the different ways November 11th is honored here in the States and overseas—what does that reveal to you about the different ways the world views the end of World War I?

CS: You know, World War I does not have a lot of resonance in America. I’ve wondered why that is. It really was a devastating war—20 million people killed, 65 million soldiers marshaled into a war in which three empires were toppled. It really changed the world. But we don’t reflect on it a lot. World War II was the beginning of the “American Century,” as we say. World War I, as most historians would see it, just led to World War II. It was such a flawed peace agreement.

But one of the things that has really struck me, as someone who has covered conflict around the world, is that if we’re going to understand the conflicts, particularly the ones I’ve covered—Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine, Iraq, the war now in Syria—the lines that make up these conflicts now, the divisions, the real flashpoints, were really formed in World War I.

And I’ve known this, because when I’m out there doing reporting, people think historically. When you go to American University of Beirut, or talk to scholars on Iraq, or when you’re on the ground talking to political leaders or tribal leaders who know their history, they all talk about the lines that made up the modern Middle East, which were shaped by the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.

That sounds like some boring history lesson that we all ignored; we were probably cutting class, not listening. It really matters. It really matters that we understand this history, because of the arrogance and the ignorance of the imperial powers that created the lines of the modern nation-states, like Iraq for example, completely ignoring the lines between the Kurdish and the Sunni and the Shi’a and other minority groups. Not to mention the complex overlay of the tribal leadership structures.

They tried to just put them all together in one package for the colonial convenience of the British Empire. They literally took a line and looped it around Mosul because they had just discovered the northern oil fields.

That’s the kind of arrogance that went into drawing up the map of the world, and we wonder why it’s coming apart at the seams. It’s because it was never stitched together in a way that thought of the people who lived there.

We might not know that history, but I can assure you ISIS does. I’ve got an anecdote from this reporting trip. We started reporting on this as a team on June 28th, which is the anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. Archduke Ferdinand was killed by a Serbian nationalist. This kid was like seventeen years old. And he shot and killed the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Big event, huge turning point. Really started the world towards war.

I was thinking about that as a correspondent who covered Sarajevo. I covered the Balkans, and of course Serbian nationalism is still rearing its head; it’s still simmering right under the surface of a very unsettled peace, if you could even call it that. You can feel it in Sarajevo these days.

So we were reporting on how the war still lingers and whispers in shadows. And I’m standing there on the bridge, right where the assassination happened, following the live Twitter feed of ISIS in Iraq on the same day, June 28th, 2014—the exact 100th anniversary of the assassination—and ISIS is live-tweeting the invasion from Syria into Iraq as they cross the border, saying, “This is the Sykes-Picot Line, and we don’t pay any attention to it, and we’re going to keep crossing the Sykes-Picot Line.” They were live-tweeting under the hashtag #SykesPicotOver.

ISIS knows its history. We need to know the history if we’re going to really understand what motivates them, and if we’re going to stand strong against their warped interpretation of history. We need to know our own history if we’re going to interpret it in a way that’s really positive for social justice, and that’s going to think about finding peace for the people that live there.

“The Kurdish state, which is emerging out of this really tense tinderbox of a moment right now, is going to expect independence. They’ve fought hard for it; they’ve shown a democratic tradition that is stronger than anything else I’ve seen in that part of the world.”

CM: You explain that your report undertook a six-month-long reporting effort to try to understand the legacy of the “war to end all wars,” and how the end of that war became known as the “peace to end all peace.”

Yet Nick Danforth wrote in The Atlantic in September 2013, “the idea that better borders drawn with careful attention to the region’s ethnic and religious diversity would have spared the Middle East a century’s worth of violence is especially provocative at a moment when Western powers weigh the merits of intervention in the region. Unfortunately, this critique overstates how arbitrary today’s Middle East borders really are, overlooks how arbitrary every other border in the world is, implies that better borders were possible, and ignores the cyclical imperial practices that actually did sow conflict in the region.”

Danforth goes on to argue that many of the borders were actually drawn long before World War I. Is the peace to end all peace, as your project describes it, about more than the drawing of borders, and how do you feel about Danforth’s assessment?

CS: I think we have to understand how those lines were shaped, and yes, we need to go back and look at other arbitrary lines in history. But the lines of World War I are global lines.

I’ve covered, for example, Boko Haram in Nigeria. Northern Muslim kingdom, Southern Christian kingdom, thrown together for British colonial convenience. And that arrogance, again, created a country with a deep fault line in the middle belt where the Muslim population was pushing down and the Christian population pushing up, and that’s created clashes there throughout history—really intense clashes right now.

And Boko Haram grows out of a resistance to that history. As you know, boko haram means “Western education is a sin” in a combination of the local dialect and Arabic.

We have to understand the history. These forces don’t just happen out of the blue. That’s as warped an understanding as thinking these disturbing weather patterns came out of nowhere. They come from the place from which we create those patterns. We are responsible. We have to understand the history.

We have to dig into the arrogance of colonialism and imperialism, and make sure we don’t repeat the same mistakes. We have to have a much more complex understanding of what it means to be self-governed, and what it means to be independent. The Wilsonian ideal, articulated in 1919, the end of World War I, at Versailles—Wilson talked about this idea of independence, self governance.

If we really believe in that as a country—which we proclaim we do, which President Obama proclaimed he did in 2009 in June in Cairo, when he said “democracy is a universal right”—if we really believe in that, and it’s not just rhetoric, I think we can provide a lot of leadership in the world. But it means we have to recognize what people want in the countries where they live.

Too often, we thwart democracy. We favor stability and our own national interest. We’re going to need a much more layered understanding of history if we’re really going to change the world. And we shouldn’t be afraid to try to change it, because it really isn’t working right now.

CM: You’re pointing back one hundred years to Sykes-Picot, but there are other people who are saying that’s not the problem with Iraq; the problem is that Sunni and Shi’a and the Kurd have been at each other’s throats since 632 AD, you know, for 1400 years. A lot of people think the Bush Administration used that as an excuse for why the war wasn’t going the way they wanted it to go during the occupation of Iraq from 2003 to 2008.

Did the Bush Administration just exploit that 1400-year “divide” between Sunni, Shi’a and Kurd, or is that also a reality?

CS: Does the United States exploit different divisions within Iraq? That’s fair to look at. But it’s much more important to look at the long history of how Arab leaders themselves have exploited these divisions.

Saddam Hussein played the Sunni against the Shi’a against the Kurd for decades. Sometimes with U.S. support. This notion of playing the sides against each other is as ancient as the Middle East itself. But there were 400 years under Ottoman rule when there was a different system of self-governance.

Not that the Ottomans were anything we want to emulate. They were a pretty brutal empire. But they did understand local governance in some sophisticated ways. We need to be better than the past. We need to improve upon the past, not repeat the past. The Ottomans played the divide-and-conquer game, but they actually played it fairly effectively, with clear lines of local governance.

I think it’s time to reconceptualize the best way for people to govern themselves. The Kurdish state, which is emerging out of this really tense tinderbox of a moment right now, is going to expect independence. They’ve fought hard for it; they’ve shown a democratic tradition that is stronger than anything else I’ve seen in that part of the world. And there are going to be questions about whether or not we support that. How we support it, and how is it going to work, and how do you create the kind of diplomacy that’s going to allow it to work?

I think the same is going to be true of Iraq as it redefines itself, perhaps in a federalist state, I don’t know. The United States needs to play a much more active role in leadership about how to build democracy. Not putting more military weaponry in and more troops. When are we going to step it up and bring our best ideas to the table?

“This is a time of revolution in media. It’s like the Middle Ages of journalism right now. It’s a time of the collapse of old empires, and the rising up of new city-states.”

CM: You write, (as you were just saying), “when the Islamic State fighters were bulldozing their way across the border between Syria and Iraq in June, they were live-tweeting under the hashtag #SykesPicotOver,” in reference to the 1916 treaty during World War I that drew the lines on the map for places like Iraq.

Do you think, though, that this is driven not by historical reality but by Islamic State politics and their exploitation of anything anti-Western? Is this just part of a propaganda model? Do you think that this is about history, or is this about exploiting something in history?

CS: That’s a great question. I think they do want to write a new narrative and breathe into it what I would consider a very dark theological interpretation of militant Islam that is warped and wrong and very far from the true tenets of the faith, based on every person I know and respect who believes in that faith. I have not met many people who really embrace the death cult that is the Islamic State.

It’s very hard for those of us who live in a liberal democracy like the United States to recognize when something is this absolutely dark, wrong, evil, and needs to be confronted head-on. I think we are in a moment like that. And I don’t say that lightly. I am not a fear-monger. This is not about Islamophobia. I’ve resisted those dark impulses for my whole life covering the Middle East.

That said, watching what they did killing my friend, Jim Foley, who worked with Global Post, who was a friend and a colleague, and then watching them again publicly execute others including Stephen Sotloff, another American journalist—ISIS is directly targeting journalism, directly targeting people who want to be there on the ground to try to tell the truth. Let’s have no illusions about who they are, what they are, and what they represent.

Sometimes in journalism we need to bring stark clarity, and I think this is one of those cases. ISIS is imposing a narrative that is really perilous and dark, and has the ability to change the Middle East. We’ve been ignoring the fact that the Middle East is coming undone for a long time. I don’t think we can do that anymore.

We’ve got to be aware, we’ve got to be attuned; we need that ground truth if we’re really going to know how to play a positive role in shaping the energy and yearning for change that was expressed in the Arab Spring. People are tired of living under dictatorship; they’re tired of living under imperial control; they’re tired of war.

The people I know in the Middle East and in Iraq are good people. They want security, they want peace. And we have got to fight harder to find more effective ways, particularly diplomatically and politically, to support that.

“The Arab Spring presented an enormous opportunity to put forward some of the ideals that we hold to be true, like democracy as a universal principle. Where were we in supporting that in Egypt when there was a military coup?”

The problem is that the economics of news these days is shifting dramatically under our feet. The great American newspapers that used to cover the world, the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, Philadelphia Enquirer—all those great big-city newspapers used to have foreign correspondents out there in the world.

All of those foreign news operations are closed. Over. They don’t have foreign editors anymore. They don’t have people out in the world, covering the world. They rely on newswires; information is being consolidated into a corporate news front because it’s very hard to make it work as a business right now.

The Boston Globe didn’t close its foreign bureaus because it didn’t want to cover international news anymore. It closed them because they couldn’t sustain it financially. As the web has dramatically changed the landscape of journalism, newspapers are struggling, as we know. The business model is flawed. We need a new one. For sure.

But this is a time of revolution in media. It is a time to create new news organizations. It’s like the Middle Ages of journalism right now. It’s a time of the collapse of old empires, and the rising up of these new city-states. It’s a very confusing time, as the Middle Ages were a confusing time. People were, like, putting leeches on to cure illnesses. We live in a time when we don’t know exactly what’s going to work, either. But it’s a great time to put on some beat up old armor and go out there and slay some dragons. Because there are a lot of things that need attention in the world.

And you can do it right now in journalism, and you can do it in a way where you can self-publish, you can get the message out there, you can connect with organizations like ours that want to really bring the old-school values of good journalism to a new generation that is absolutely amazing in its energy but needs mentoring, needs training, needs support in order to work deeply and safely.

The Ground Truth Project is all about that. We want to be a beacon for this next generation. Because I’m getting old, man, I’m fifty-two, and I want to hand it off now. I want to hand it off to young people—they’re going to be the ones who figure it out. But we need them to get on board, and we need them to do great journalism, and we need them to be committed. Not just sitting back and being snarky, but going forward and kicking ass.

CM: You write, “President Obama may have succeeded in keeping a campaign promise to bring the troops home from what he called a ‘dumb’ war, but now the unfinished momentum of history is pulling the U.S. back into war in Iraq. For now the American involvement is limited to airstrikes and some 1,500 advisers on the ground, but most regional military experts are under no illusion that this faltering approach will last, and there is a growing consensus that the U.S. will indeed need ground troops to succeed in Obama’s vow to ‘degrade and destroy’ the Islamic State.”

In fact, NBC News reported this week, “General Martin Dempsey, the nation’s highest-ranking general, said on Thursday that he considering recommending that American troops fight alongside Iraqi forces to retake the city of Mosul from ISIS militants.

“In testimony to the House Armed Services Committee, General Dempsey said, ‘I’m not predicting at this point that I would recommend that those Iraqi forces in Mosul and along the border would need to be accompanied by U.S. forces, but we are certainly considering it.’”

What impact would that have on the potential for Iraq to break up?

CS: I think Iraq pulling apart is inevitable. There’s an inextricable, natural law of gravity at play. People want to govern themselves, and they don’t want to be bullied and bossed around by others.

Sadly, the Shi’a government, rather than being an inclusive government, was a punishing government to the Sunni population, which is why the city of Mosul allowed the Islamic State to come in. They figured, “well, we’re getting treated so poorly, who are these guys? At least they’re Sunni; maybe they’ll help us out.”

I’ve talked to people who live in Mosul. They are under no illusion that that was a huge mistake. Everyone I’ve talked to understands the anti-democratic—to put it lightly—impulses of ISIS. They don’t want those guys in there. But they are also willing to admit they sure as hell didn’t want to be under Shi’a-dominated government, either.

What we have is a moment of malaise, of great cynicism, a sense of uncertainty. It is pulling apart, and it’s going to pull apart. So the imposition of U.S. forces on the ground—you know, god, the last thing we need is more war. The last thing we need is to drag this country back into war and to drag Iraq back into more fighting where more thousands of innocent people are going to get killed.

At the same time the Islamic State represents great peril. And I say this with great reservation, and it pulls against what I normally say. I’m not a pacifist, but I recognize how flawed American foreign policy is. I just don’t think you can stand by and allow the Islamic State to take shape. I think ISIS represents a great enough peril to any sense of human freedom that we have to confront it.

So I’m not against an effective use of troops on the ground to do that. It exposes the complete failure of the American experience in Iraq that we spent hundreds of billions of dollars on training an Iraqi army that fell apart. We spent hundreds of billions of dollars on propping up a ‘democracy’ that disintegrated. When are we going to get better, as a country, at putting forward our ideas to the world in a way that’s effective?

“We need to have an ear to the ground. We need to really listen to the voices coming out of the Middle East right now, because we’re living in a historical moment.”

I think that we as voters, we as journalists, we as Americans, we’ve got to be a lot tougher about making sure our government lives up to the ideals we talk about, and really fight for them. We have got to get some really hardcore journalism going to play a role in understanding the complexity of the moment so we can move forward in a way that is better than the way we have conducted policy—militarily, politically, and diplomatically—throughout the Middle East.

CM: I’m not really certain what the U.S. policy is in Iraq.

CS: U.S. policy is in disarray. The Obama Administration has been supremely distracted on the Middle East. They have not had a clear, governing principle to their foreign policy in the Middle East.

The Arab Spring presented an enormous opportunity to put forward some of the ideals that we hold to be true, like democracy as a universal principle. Where were we in supporting that in Egypt when there was a military coup over the 4th of July weekend? John Kerry was off windsurfing. Literally.

The Muslim Brotherhood, which was democratically elected in Egypt, was no walk in the park, nor very democratic. For sure. But they were elected. And the Egyptian people are smart, and the Egyptian people care about their country, and they have a wonderfully complex sense of their own history, and I think they would have thrown the bums out eventually. Voted them out.

Why did we allow the military to come in and reimpose the junta on the Egyptian people? We did that because we believe in stability. There was a turning point over the summer of 2013; there was a recognition that this rhetoric of democracy is going to get us in trouble because it’s not going to protect our national interest. And we hit a moment where the ideal of Wilsonian self-governance conflicted with our own yearning for security, stability, and national interest.

This is a historic moment. This is a 100-year event in the Middle East. It’s challenging all of the basic, raw precepts that have held the Middle East together, including the national boundaries formed in World War I.

The United States has got to get a much more clear policy, and have the courage to execute it. If you believe in democracy, then let it work. And really work at it. I don’t think we work hard enough as a country at effectively putting forward those ideas, supporting them, funding them, helping people find that path forward. And then allowing them to self-govern, accepting that they’re now among a community of nations, as are we, in which we have to be respectful.

Instead, we’re flailing. In this chaos there’s a vacuum, and that vacuum is being filled with tyranny. Whether that’s a reimposition of dictatorship in Syria, a military junta in Egypt, or this dark death cult of ISIS in the caliphate they’ve created that straddles Syria and Iraq.

CM: One last question for you Charlie, and it is the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response. You write that “Djene Rhys Bajalan, a professor of history at the American University at Sulaymaniyah, said the historical parallels between the current moment and World War I are alive in the rhetoric of the ongoing conflict. But as he points out, there is a profound difference. ‘When the lines were drawn at the end of the First World War, they were drawn without the participation of the people. The fundamental difference today is that the people here, living in Iraq, now are in the process of redrawing the borders themselves.’”

So here’s my Question from Hell. Does that mean that what the Islamic State is doing—no matter how cruel, how murderous—could be better for long-term stability in the Middle East than the treaty to end World War I was?

CS: I think the question is fair. What I would say is that anyone who imposes their will at gunpoint, by hanging people in the streets, by taking hostages and executing them through beheadings, forcing them at knifepoint to say things against their family, against their country—that is so dark a force, and will be so resisted by any human being, anyone with any human nature, that we shouldn’t misinterpret the tyranny of ISIS as an expression of democracy any more than we should interpret the gathering steam that we see Assad getting and controlling Syria again as an expression of a democratic vote for him.

What’s happening on the ground in the Middle East is an absolute rejection of decades of war, a rejection of decades of oppression and tyranny under dictatorships and flawed Western imperial foreign policy. It’s very hard to hear the voices of the people through all the gunfire and all the fear. But we’ve got to be on the ground and we’ve got to listen.

There are journalists who are courageous as hell who are out there every day reporting, and they’re not just Western journalists. A lot of them are local journalists, from Iraq, from Syria. Almost ninety percent of the journalists who have been killed in the last few years are local journalists. They work under peril. We need to think about the people out there trying to find the truth.

And I would ask, as an American citizen, where is our State Department? Are you on the ground, taking the risks to hear people? I know it’s hard, and I know it’s put people in peril. I understand that Benghazi was an expression of what can happen when you do have an ambassador who really does go out there and try to meet with people. But we can’t give up. Ground truth matters.

Ground truth, in my mind, is what’s missing from the equation. We need to have an ear to the ground. And we need to really listen to the voices coming out of the Middle East right now, because we’re living in a historical moment.

CM: Charlie, thanks so much for being back on our show.

CS: Love to talk to you. I love what you guys are doing. Keep it up.

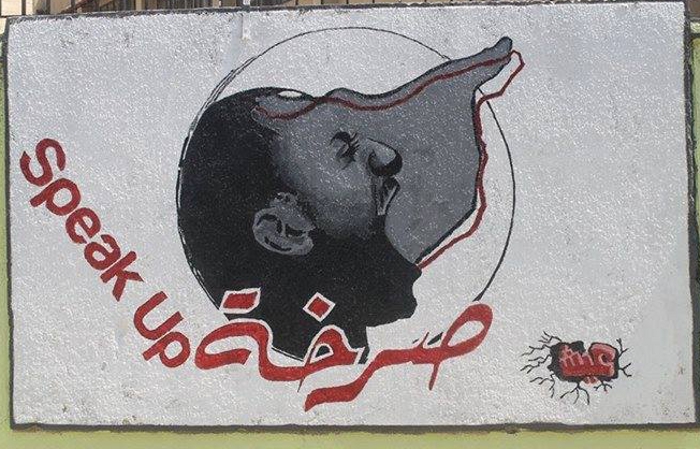

Featured Image: ISIS militants crossing the Iraqi-Syrian “border” in commandeered U.S. vehicles