Transcribed from the 23 August 2014 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“Kenilworth was founded in 1889 by Joseph Sears, and he had four great principles that he put in its founding documents: no alleys; no fences; large, architect-designed houses; and no Jews or Negroes. The first three expired after twenty years, but the fourth one never expired.”

Chuck Mertz: Sociologist James W. Loewen taught race relations for twenty years at the University of Vermont. He wrote the 2005 book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, and his second edition of Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your History Textbook Got Wrong was just published.

Good morning, Jim.

James Loewen: Hi! Glad to be with you.

CM: It’s great to have you on the show.

Oddly enough, I just found out our correspondent in Rio de Janeiro used to visit Ferguson when he was a kid, because his grandmother lived there. I asked him if he was surprised that this happened in Ferguson, and he said he was, because when he was a kid, thirty years ago, it was an all-white town. But he found out from a relative that at one point they put a wall right through Ferguson, separating the black side from the white side, and saying that after sundown blacks weren’t safe.

You weren’t certain if Ferguson was actually a sundown town. Why don’t you tell people what a sundown town is, and why that’s important.

JL: Sure. You guys are located in Chicago, are you not? I grew up in Decatur, Illinois, right in the center of the state, and it turned out that I grew up surrounded by sundown towns, but I never knew it!

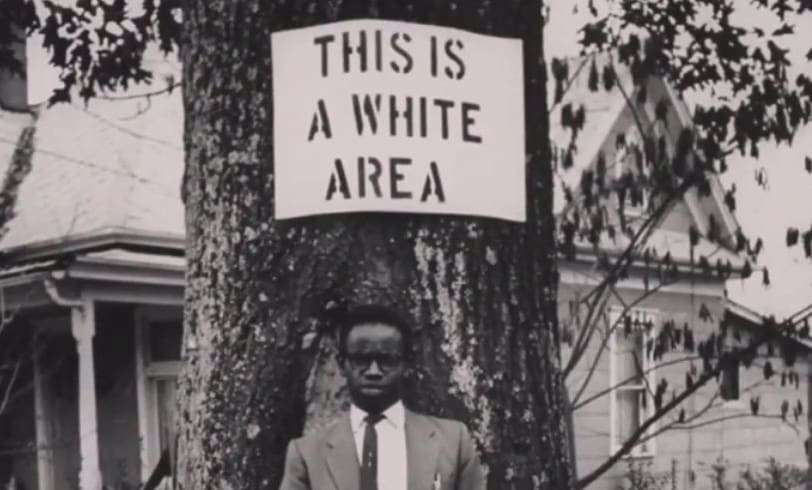

A sundown town is a town that for decades was (and some of them still are) all white on purpose. They get their name because some of these towns—like, for instance Pekin, Illinois, or Manitowoc, Wisconsin—actually had a sign at their city limits saying (and yes I have to use the word) “Nigger, don’t let the sun go down on you in Manitowoc.”

They didn’t have to have a sign to be a sundown town. Most of them didn’t have a sign, they just had a policy that black folks are not allowed to live there. Most of the suburbs of Chicago—and, in fact, most of the suburbs of every northern city and many southern cities—went in as sundown towns.

But many independent towns did, too, and I had no idea when I was researching this. I thought I was going to discover maybe ten of these towns in Illinois, and maybe fifty across the country. But I am now at a count of 506 sundown towns in Illinois alone, which is 70% of all towns in Illinois. A similar percentage afflicted Oregon and Indiana and various other northern states.

CM: So what does that say about you and me? What does that say about us when we are so surprised at the number of towns that had these “sundown” policies?

JL: Well, it’s just amazing. And really, you pointed to two problems. First of all, isn’t it astounding that so many towns had this policy? And as I say, some still do. And second of all, isn’t it astounding that hopefully intelligent people like yourself and myself didn’t know it?

CM: It’s not astounding, it’s disturbing.

JL: Yes, it is. Well, what happened specifically in Ferguson is this: I did not know about that wall story, and I’m going to have to research that. I know about a very famous wall in Detroit that relates to this same issue. And Detroit actually was ringed by even more sundown suburbs than Chicago or than St. Louis. It’s one of the reasons why Detroit is in such a mess today.

But Ferguson, ironically, had a small black community all the way back to the Civil War. I don’t know how big it got, but I have done the research since 1940. In 1940, Ferguson had about 5,700 people in all, and of that, 38 were African Americans. A small black community. Now, they only lived in one area, and the rest of the place was pretty sundown, but still, that gets it off my list. It does not qualify as being a sundown town.

But then, between 1940 and 1960, Ferguson did what it could to become a sundown town. Here are the population numbers (they are astounding): Ferguson explodes by almost four times. It goes from 5,700 people to 22,000. Meanwhile, St. Louis draws an exploding black population that goes from just under 150,000 to 300,000. So with those two population growths in mind, you would expect that the black population of Ferguson would have risen substantially. But instead it falls from 36 to 15. It falls by 60%. Fifteen people is like, three or four families.

Now, how did they achieve that? I know of three methods. First, they put a chain across the main street that connected Ferguson to Kinloch. Kinloch is a little black suburb that is just to the west of Ferguson. Now, when you put a chain across that street, it’s still possible to get from Kinloch into Ferguson, you just have to go around and come in through a different side. But that certainly signals to black people in general, and folks from Kinloch in particular, “we don’t want you.”

The second thing they did was they started—or maybe they just intensified—DWB policing. Probably your audience knows I’m talking about Driving While Black. The police force would stop folks who are black—and they could even do it politely: “What’s your business in town?” Which gets across the idea that you have no business in town, there’s something wrong with you being in this town, and don’t let it happen again.

The third thing, of course, was the usual. Namely, realtors wouldn’t show houses in white neighborhoods—which is essentially all of Ferguson except one little area—to black would-be residents.

So that’s how it occurred. It never quite reached sundown, but it tried. And now what we see, I think, is two results of that. The first result is that the town became 70% black. And I’m sure it’s going to become blacker. This happened, too, in a lot of Chicago suburbs, particularly on the south and southwest sides.

That seems counterintuitive. So there are these suburbs that were sundown, and then suddenly—well, by 1970 in the case of Ferguson—there’s 170 black folks in town. Now, that’s not very many out of a population of 22,000. But still, if you were raised with the idea that black folks are inferior, that they are a problem, that they’re such a big problem that we need to keep them entirely out of town, that they are crime-prone and so-on—well then with 165 people, what are you going to do? You want to move. And so a lot of white folks started moving further out, to the exurbs. Often they were still sundown.

The second thing that happens, then, is that you have what we call a “second generation” sundown town problem. That is, we still have this overwhelmingly white police force with sundown town attitudes.

CM: On Thursday, a freelancer working with Al-Jazeera by the name of Ryan L. Schuessler posted this on his website: “I will not be returning to Ferguson. After what I saw last night, I will not be returning. The behavior and the number of journalists there is so appalling that I cannot in good conscience continue to be a part of the spectacle. I’ve seen cameramen yelling at residents in public meetings for standing in the way of their camera; cameramen yelling at community leaders for stepping away from podium microphones to better talk to residents directly; TV crews making small talk and laughing at the spot where Mike Brown was killed as residents prayed and mourned. A TV crew of a to-be-left-unnamed cable news network taking pieces out of a Ferguson business retaining wall to weigh down their tent. Another major TV network rented out a gated parking lot for their one camera, not letting people in, safely reporting the news on the other side of a tall fence.”

And on Thursday a news photographer by the name of Abe Van Dyke tweeted, “Ferguson, I firmly believe the media is now more of a hindrance than a benefit, so I’ll be leaving Missouri tomorrow.”

How do you rate the way the media has portrayed what’s happening in Ferguson? And what do you think is the big story that’s being missed?

JL: I actually think that the media, especially at the beginning, played a very helpful role. Of course, we are in this era of complex media in which the media aren’t just the television cameras anymore, but they’re you and me who tweet, they are whoever has a cellphone and uses the and then posts it on Youtube or whatever.

And there’s this story about a black Washington Post reporter, Wesley Lowery. So there was a McDonald’s in Ferguson that was kind of the central place where media were gathering. For one thing, it was a WiFi hotspot. For another thing, it’s not too expensive, you know? You can buy a cup of coffee for a dollar. So he and another black journalist had ensconced themselves into this booth and had spread out their stuff. McDonald’s wasn’t upset about this. They had ordered something, you know? And they were working with their material and they were probably tweeting and writing their stories and so on. And the police came over and decided to close McDonald’s.

And so this Washington Post reporter, perfectly reasonably, said, “Okay, yes, give me just a minute, I have to gather up my stuff.” So he was gathering up his stuff, and then he got another order that he had to leave this way, now, so he gathers up really fast and left that way. Only when he got to that door, that door wasn’t being used and the policeman said, “Nope, you can’t get out here.”

The upshot of all this was he got arrested, as did his tablemate, and they both spent the night in jail.

Now, they were black, admittedly. I guess that’s a problem. But otherwise, they’re Washington Post reporters who were peaceably occupying a booth at McDonald’s. So in that sense, the problem wasn’t the media. The problem was the police.

Now, that account you just read—certainly the media are arrogant, or can be. They can be arrogant in Ferguson and they can be arrogant in white settings as well. So that’s a problem. But the media play a complex role in a complex society, and I don’t think that they are the problem here. I think the problem is leftover sundown town attitudes on the part of the police force.

“There is a period in American history called the nadir of race relations, the era from 1890 to 1940, when the United States actually went backward in race relations, got more and more racist. This is almost completely left out of American history textbooks.”

CM: You write that “every former and current sundown town and suburb in the U.S needs to give up the practice explicitly and openly. That will relieve the black housing pressure, so interracial towns will no longer tend to go all-black. It will also clear the air about our recent racist past, allowing locales all across the U.S. to move forward.”

JL: I’m so glad you read that passage. Let me just exemplify that in your metropolitan area, in Chicago. The places that get all the headlines are the places like Ferguson, but you know, southern and southwestern and western suburbs of Chicago, from 1950 to the present, have on occasion rioted or had disturbances by white folks, basically as black folks are moving in. This happened in Cicero, Illinois, in 1951, ’61, ’71, and ’81. Seemed to happen on ten-year intervals. Cicero, of course, is now over 80% Mexican-American and has over a thousand black folks living in it, so it’s no longer a sundown town. But it was for a long time.

But the seed of the problem in the Chicago metropolitan area is Kenilworth, and places like Kenilworth. Kenilworth is, of course, the most prestigious and richest single suburb of Chicago, and it’s on the North Shore, just above Evanston, and it doesn’t get any headlines. But Kenilworth was founded in 1889 by Joseph Sears, and he had four great principles that he put in its founding documents: no alleys, no fences, large architect-designed houses, and no Jews or Negroes. The first three expired after twenty years, but the fourth one never expired.

Well, since then, Kenilworth has had exactly two black families. One of them lasted four months. The other one lasted twelve years. Did okay, too, in a way, but left after twelve years. The last I knew—both on the census and from checking with perhaps the most important realtor in town—there isn’t a single black family in Kenilworth today as far as I know.

And that’s the seed of the problem. Because people in a town like Oak Park struggle to keep the town interracial. And the reason they struggle is because some white folks get richer and richer, and they want to express their wealth. Now I wish they’d express their wealth by endowing an entire college or something. But instead they want to buy a bigger and even more pretentious home and so on, so they want to move to Kenilworth. Not because it’s all white, but just because it’s more prestigious.

And they do just that, and it makes it hard for interracial suburbs—like Oak Park and many of the suburbs of Chicago now are—to stay interracial. They tend to go blacker and blacker. So I think what we need to start doing is attacking the prestige of the “prestigious” all-white suburbs like Kenilworth.

CM: Is the only way that we could deal with the problem of sundown towns through the courts? Do we have to avoid the political route? Because the political will doesn’t seem to be there. Do we have to rely on the justice system?

JL: In the case of sundown towns, I think people can make a difference. Both white people and black people. White people can raise the issue. If you live in a sundown town, you can bring it up. Incidentally, it is provable.

I have a three step program for getting over sundown towns. And I want to propose that your listeners can participate.

The first step is to admit it. To admit, yes, we did have this practice, formally or informally.

The next thing they can do is they can get their town to apologize for it. “We did this, and it was wrong, and we’re sorry…”

And then the third step is: “…and we don’t do it anymore.” And that third step needs to have some teeth. “We are hiring black police. We’re hiring black schoolteachers. We’re hiring black garbage collectors. And we’re helping locate them residentially in the town, in the city.”

If you take those three steps, you’re off my list.

If you took those three steps, you have improved race relations in America. And you didn’t have to use the courts, and you didn’t have to use the president.

CM: Again: admit, apologize, and make sure you don’t do it again, ever. Legislate it, regulate it, make sure it never happens again.

I wanted to talk more about Lies My Teacher Told Me. You point out how history textbooks are thick, they’re heavy, they’re full of ‘facts,’ you’re supposed to do rote learning, there is no investigation that’s being done, and all of the passion of them is stripped out of it. It’s almost as if you’re studying literature and you’re reading Romeo and Juliet but they take the love story out, because that’s the part that might lead to discussion and controversy.

So when it comes to our history textbooks and the inaccuracies in the way that history is taught, how does that inform the way we view race in this country?

JL: Oh, it’s terrible. There is a period in American history called the nadir of race relations, the era from 1890 to 1940. It is that era in which sundown towns grew up, and towns went sundown. They passed an ordinance that they should never have any black population, or drove out the black population they had. In this nadir period, the United States actually went backward in race relations, got more and more racist.

This is almost completely left out of American history textbooks. I say almost, because one of the eighteen textbooks that I analyzed for the second edition of Lies My Teacher Told Me mentions it—not by name, but it does mention it. The other seventeen don’t say anything.

And why don’t they? Because their underlying and basic story line is onward and upward, better and better, the United States started out great and has gotten better ever since. When you’ve got that story line, it’s very hard for you to fit in: “oops, for fifty years there, we got worse and worse with regard to race relations.” So let’s not even think about it—a lot of people don’t even know about it, including historians—and we’re certainly not going to write about it in our textbooks.

So this is one of many ways that our history textbooks systematically make us stupid, and make it harder for us to think about race relations. Among other things.

CM: I really appreciate you being on the show today, Jim. It has been an honor.

JL: I’m delighted. Thank you.