Transcribed from the 29 November episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“It’s worth repeating: police. We’re not talking about a crime that was carried out by organized crime. These were uniformed officers.”

Chuck Mertz: Dozens of people victimized by police, leading to nationwide protests…no, we’re not talking about Ferguson, Missouri. Here to tell us about the disappearances that have set Mexico on fire is irregular correspondent Laura Carlsen. She is a Foreign Policy in Focus columnist, a policy analyst and director of the Americas Program at the Center for International Policy, and a writer and editor of The Americas Updater. She is based in Mexico City. Good morning, Laura.

Laura Carlsen: Good morning, Chuck.

CM: One of the things that was breaking last week was President Obama’s announcement about immigration policy. I started thinking about how that policy might relate to the 43 students that were disappeared in Mexico. Then I started thinking, maybe it’s the trade policy. Maybe it’s the War on Drugs. I’m not too sure which is more frightening. Or maybe our trade policy, our War on Drugs policy, our immigration policy are combining to create the situation in Mexico, or at least contribute to it…

Is there an immigration policy, a trade policy, a drug war policy, or any type of policy that the U.S. could have, that would have made the circumstances for the 43 students to be disappeared less likely?

LC: That’s a complicated question, Chuck, but it’s a very good question. Yes. There could be.

It’s very clear that public policy—including U.S. public policy towards Mexico—is responsible, at least in part, for what happened to these 43 students, and the six persons who were also killed the same night in these terrible events.

And it’s also true that these policies go together, although they have apparent contradictions. Together they form a policy of regional integration that has to do with opening up Mexico to U.S. transnational interests, and with controlling Mexico for reasons that have much more to do with U.S. national security than with the security of the people of either country, and certainly not with the security of Mexico itself. Because as we know, since the United States has been promoting this drug war there have been about 100,000 people killed in this sharp spike of violence, despite the fact that it was supposed to be exactly the opposite.

When you see this in the framework of the United States taking regional control of North America, opening it up to foreign investment, and then seeking to protect those foreign investments within Mexico, it begins to make sense why these apparently contradictory policies are not so contradictory. Behind all of them are very, very powerful economic interests.

The case of the drug war is probably the most directly related to what happened in Iguala, Guerrero, on the night of September 26th, when local police (and it’s worth repeating: police. We’re not talking about a crime that was carried out by organized crime. These were uniformed officers) opened fire on three busloads of students, killing three of them, and taking into custody 43 who have never been heard from since.

Those are the 43 students that are now being searched for all over Guerrero, and have caused the huge demonstrations—hundreds of thousands of people in the streets of Mexico City—calling for their return.

CM: Why do you think the protests happened this time? There have been plenty of massacres since 2010. There have been plenty of mass killings. There have been plenty of mass graves found. This week there was yet another mass grave found, of eleven bodies—they haven’t determined yet if those include any of the students who disappeared on September 26th.

So why this time? Why is it different, seeing as how there have been larger mass killings in the last few years. What made this one so unique?

LC: There are a couple of factors. One thing was that it was so blatant, that the police were so clearly involved in it.

The other thing has to do with this rural school, a teachers’ college. These colleges were formed specifically to train rural teachers, and the people that go to them are mostly from surrounding communities. They are peasant communities, they are indigenous communities, they are very poor communities. And they have a strong commitment not only to getting professional training so they can have better lives for themselves, but also to creating better conditions for their communities.

They have explicitly revolutionary ideals that they teach within these colleges, because they were formed specifically for that purpose right after the Mexican revolution, which was a quite progressive revolution. If you look at the original constitution, they called for social equality, they called for reclaiming the rights of peasants and indigenous people.

That’s been a thorn in the side of the government. The government’s been trying to eliminate these schools for quite a while now, especially since taking on this neoliberal economic model. The peasant farmers working at most of these schools are working on social forms created in the revolution, so there’s been a real political conflict between the neoliberal government (especially now, with Peña Nieto and his whole package of structural reforms, including privatization of the oil industry) and these rural schools that are known, because of these ideals, as a center for student activism.

In fact, these students were going into Iguala to get buses to take them to protests for the October 2nd anniversary of the massacre of students in Tlatelolco. So they’re very involved in student protests, and many people believe that there was a political motive behind the abduction of these students and the killing of others, due to the fact that the government is trying to eliminate these schools. They’ve been trying to defund them, and they consider these students to be troublemakers.

CM: You write: “The roots of the protest predate the horror in Iguala and the Peña Nieto Administration. They are, in a sense, the latest phase of the historic struggle between Mexico’s student Left and the federal government, one that has been brewing for years, if not decades. But this time the fury has moved out of the leftwing teachers colleges and restive southern states and into the rest of the country.”

Is this a brewing class war? Is that what we’re seeing? Because my understanding is that the disparity of wealth in Mexico is much greater than in the United States. And especially when you have this kind of education system that is embracing more leftwing ideas, and especially among poor people, I would imagine that this would be the start of a class war. Would you say that?

LC: Yes. I think it is. And I think it’s been going on for a while, but we’re seeing it very clearly right now. This is typical of Mexican politics. There will be latent conflict—for years, sometimes—and it will seem that society is putting up with political trends that are hurting the majority of the people, and we’ll be asking how long can this go on? And then suddenly there’ll be a single event that detonates a movement. This movement is not based on a single event, but on an accumulation of factors that have been happening for a long time.

In this case it’s the inequality, and the fact that since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), there’s been growth in the number of poor people and in the disparity, as you mentioned, between the rich and the poor. The rich are obscenely rich—one of the richest men in the world is Mexican, Carlos Slim—and the poor are extremely poor people whose children go to bed hungry.

One of the things that’s exacerbated these protests regarding the 43 disappeared students, too, is that a scandal broke out at the same time, just about a month afterward, that has to do with the $7 million mansion that the president’s family is living in. It’s actually in the name of a construction company that has hugely benefited from government contracts while Peña Nieto was both the governor of the state of Mexico and since he’s been president.

So there is this in-your-face disparity between the way that the president and his family is living, and the way that the majority of Mexicans live. That comes out as social anger. And when you add to it the fact that many people can’t even live in situations that they consider safe for themselves and their families—especially in places like Guerrero—then it’s an unsustainable situation. There are massive cries for not just the resignation of the president, but for a shake-up of the whole political system.

“In many places, drug war militarization is actually used to create partnerships between governing elites and drug cartel leaders. This is certainly the case in Iguala.”

CM: But Peña Nieto did win the 2012 election, and the alternatives to the PRI or the PAN who oppose the drug war only got a third of the vote.

So are those who side with reform, who side with the students—are those people still in the minority?

LC: In terms of numbers, and measuring minorities and majorities, there are some things we have to take into account.

First of all, Mexicans have very little experience voting in free elections, since the PRI was a one party system, essentially, for over seventy years.

Secondly, in Mexican elections, people don’t think about voting the way we think about voting, as having something to do with ‘conscience’ or even political conviction. This was particularly true of the 2012 elections; there was massive vote-buying on the part of the PRI. That means that poor people—who really don’t consider the vote to be anything that’s ever really made a difference in their lives—were willing to accept these grocery store cards that the PRI was handing out, for maybe a hundred dollars or something, in return for a vote. The PRI even had systems of checking to make sure that the person actually followed through and voted for Peña Nieto after receiving these cards and other types of economic benefits.

That was a big factor in how he won that much of the vote. Probably a much bigger factor than people being convinced that he was the best political offer in the field at that time.

There also has been a real change, I think, that has to do with people realizing that Peña Nieto is not coming through for them in a lot of ways, and that he represents this very narrow wealthy class of people.

The privatization of the oil and gas industry, and of the state-owned company PEMEX in particular, triggered a lot of that. The polls we do have show that the majority of people were against that. It was a symbol of national pride that the oil industry was nationalized in 1938 and that the foreign companies were kicked out. So now that they have them coming back in again at this point is something that really offends a lot of Mexicans.

That kind of opposition has been growing, based on those privatizations and based on some other structural reforms, including education reform, which ushered in this standardized evaluation, “No Child Left Behind,” quantitative way of looking at education that has led to many teachers protesting in the streets and many (especially poor and rural) communities—like the one this teachers college would serve—also protesting. So it’s been building up around this series of “bold initiatives” that the Peña Nieto Administration has put forward.

CM: So do you think this is not about the War on Drugs, but more about a war on education? More about a war on the public trust and public utilities?

LC: I think it’s both things. The way that the War on Drugs comes in—and this is where it gets complicated—is that the War on Drugs has never really been a war against drug cartels, in Mexico or anywhere else. We can tell that by the lack of results, and we can tell that by what they’re doing on the ground.

Here in Mexico all it’s meant is militarization, and a lot of that militarization has been used to protect investment and economic interests rather than to attack drug cartels. In fact, we see that in many places that militarization—both police and military forces—is actually used to create partnerships between governing elites and drug cartel leaders. This is certainly the case in Iguala.

In Iguala what we have seen is this: the War on Drugs takes out a big-name cartel leader, and that causes a splintering into smaller groups. And those smaller groups are far more dangerous, generally speaking, to the population than the larger cartels were. In this case we had cartel by the name of Guerreros Unidos which was virtually running the city. The mayor’s wife is from a family that is closely allied with the drug cartel, for instance. This created the situation where, in cahoots, the cartel and the city government decided to launch an overall attack on these ‘troublemaker’ students.

This kind of an incident is one we’re seeing all over, and it’s a direct result of the policy of the War on Drugs. Because before the flood of money and militarization, the cartels just kind of carried out their business, and there wasn’t that much affect on the society itself.

So the drug war does have a lot to do with it, but the drug ear is part of that larger scheme of protecting economic interests, and of course the drug trade itself, at some $38 billion a year, is one of the major economic interests that it protects.

“They’re sending out signs right now that the response to grassroots uprising will be repression. And that’s not good.”

CM: You write that “with frustration heightened by long-standing grievances with Peña Nieto, it’s far from clear just how much worse things will get.” Then you quote Cecilia, a teenager in Mexico City, saying, “We’re here to demand justice. Not just in the case of Ayotzinapa, but for all of Mexico. If there isn’t justice, the country is going to explode.”

Do you believe that an explosion is inevitable?

LC: I don’t think it’s inevitable. Up to now, the movement has concentrated on finding the students, and on being a nonviolent movement. There’s been property damage, which I think is a somewhat different thing, but overall—with the exception of small groups in which there’s some serious evidence that provocateurs could be involved—the movement has been peaceful, and that’s their idea. They’re not calling for anything that doesn’t fall within that nonviolent framework.

It depends, I guess, on what you mean by “explode.” It’s very clear that something has to change. Yesterday, Peña Nieto gave a speech presenting ten points of a new security plan, and one of the things he said is that Mexico will never be the same after this event. So even he agrees that this is the case. Of course, from there on in his security plan was a rehashing as well as an intensification of the policies that led to this problem in the first place.

Whereas the students—because this is really a youth-led movement, even though many sectors are involved—are going for a complete change in the political class. There’s not much precedent for that kind of change. Making these demands and imagining how they’ll be carried out certainly represents new territory, and it’s really impossible to predict or even postulate possible scenarios at this point.

But many sectors are getting together on the grassroots level to push for change. They’re getting behind the demand for the resignation of the president, and of course for the presentation, alive, of the 43 students, and other than that, beginning to formulate other kinds of demands as well.

This is important in itself, and means that there’s been a big change on the grassroots level that one would think would lead to other kinds of changes. I don’t think we’re looking at an immediate scenario of any kind of an armed uprising, and everyone hopes that it won’t come to that.

CM: When we announced on Facebook that you were going to be on the show, Laura, we got this comment from a listener named Maya. She writes, “Thank you so much for reporting this, sir. I feel like there is hardly any coverage on this mess. So happy to see massive turnout in Mexico City. Lousy to see the police dressed as civilians and police brutality during this. I want to believe Mexico is finally waking up.”

But can Mexico “wake up,” in the words of Maya, without U.S. approval?

LC: It’s really significant that President Obama hasn’t said anything publicly about this. There have been some State Department spokespeople—and that’s really about it—who say this crime must be investigated and blah blah blah. But nothing more than that, and certainly not any pressure.

So the United States is really unsure. But they’re watching this closely—in fact there have been reports of at least three private phone calls between Obama and Peña Nieto—and we can only assume that they’re very worried about it.

One week before this happened, Peña Nieto was in New York City. I was there then, too, because the United Nations was having a meeting on the rights of indigenous people, and there was the Climate March. So I remember Peña Nieto was given an award for Statesman of the Year! He was heralded as the up-and-coming, modernizing president. He was the darling of the international press. And of the U.S. government as well, because they have long wanted the oil and gas sectors opened up to U.S. companies.

Then he gets back and he faces the other Mexico. There’s this Mexico with this shining image abroad as an emerging economy moving forward, but then there’s the fact that police, in collusion with drug cartels, are disappearing college students and murdering their own population—for many people, that’s the real Mexico. Here in Mexico City, in fact, it is hard to understand how Mexico could have such a positive image abroad, because people here know what is happening.

There’s definitely an awakening happening in Mexico, and not just in terms of people understanding the situation—because I think many people always did; there was just an apathetic and cynical attitude towards it—but now people are really going out into the streets. And it’s different types of organizations, from union organizations to young people, to feminists—you see all of them marching together now, so there’s a real awakening.

The problem now is that there’s a strong likelihood—and we’re already seeing a lot of signs of it—that the government will respond with repression. There were eleven people, after the huge march on November 20th, that are still in police custody, and the charges against them and the evidence against them is extremely sloppy, to say the least. They just rounded people up in a big police raid after that demonstration.

And in other parts of the country we’re seeing the same things happen. So they’re sending out signs right now that the response to grassroots uprising will be repression. And that’s not good.

CM: No, that is not good at all.

Laura, it is always great to hear from you, even though it’s an incredibly depressing topic. Thank you very much.

LC: Thank you, Chuck.

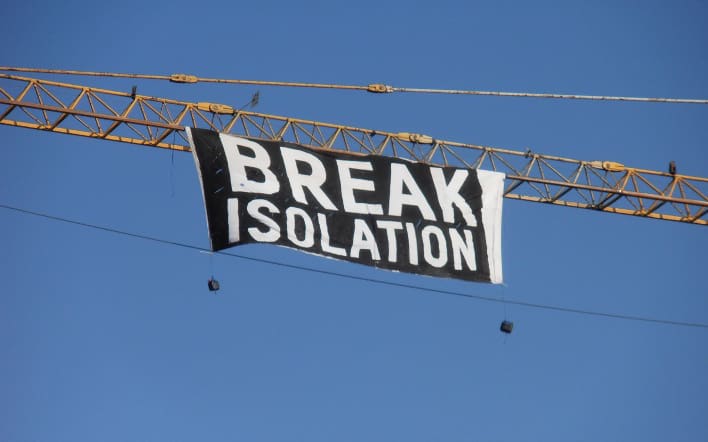

Featured image source: the excellent Regeneración journal (“El periódico de las causas justas y del pueblo organizado”)