Transcribed from the 6 December 2014 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

“This neoliberal project is being pushed incredibly hard by Snyder’s office; it is being pushed by Washington, by New York, by the White House. But I don’t think it’s going to be successful.”

Chuck Mertz: Journalist Laura Gottesdiener has written the TomDispatch piece Two Detroits, Separate and Unequal: A Journey Across a City Divided. Welcome back to This is Hell!, Laura.

Laura Gottesdiener: Thanks for having me.

CM: You start by writing about being driven around Detroit’s well-heeled Palmer Woods neighborhood, a neighborhood that has defined “rich” in Detroit for generations. You write that the guy giving you the tour is commander Dale Brown, founder of Threat Management, a private security company. “Brown’s officers, with their distinctly paramilitary aesthetic, are among the most recognizable of a burgeoning number of private security personnel and surveillance systems scattered across neighborhoods in the former Motor City that people with money have decided are worth protecting.”

Does his firm have the same kind of oversight or restrictions that regular police do? Can they perform the same duties?

LG: Well, they don’t have the level of impunity that the public police do in this country. We’re obviously in a moment right now when widespread impunity and killings by police all across the country are being protested and challenged very vocally.

The private security companies that you’re seeing in Detroit don’t enjoy the level of impunity that the Detroit PD does. What they have instead of impunity is an incredibly lucrative business model. They enjoy billions of dollars coming from corporations or neighborhood associations to patrol and protect and guard—and exclude—people.

Threat Management is an interesting example, because it works not only with upscale neighborhood associations like Palmer Woods and Sherwood Forest, but it also works with community groups like Michigan Welfare Rights Organization to provide security for their events free of charge or at a very low cost. So Threat Management really straddles both worlds in Detroit. That’s why I wanted to follow commander Dale Brown. He is one of the few people who sees the two worlds in Detroit.

But there are also private security and surveillance firms that are not interested in supporting grassroots community groups. They are only interested in securing, for example, the downtown district of Detroit, which is undergoing either revitalization or gentrification (depending on who you ask). The New York Times praises this, but community leaders in Detroit say that a billionaire came into the city, bought up all of downtown, installed hundreds of security cameras, put a private security guard on every corner, and basically said, “only middle class gentrifiers are allowed into this area, and everybody else should get out.”

So the issue of private security, and the direction that Detroit is taking post-bankruptcy, is a very interesting story that few people are really scrutinizing. When I look at the national news, I only see that Detroit is out of bankruptcy and this is a great thing. Now, we all want Detroit to be out of bankruptcy—but Detroit never had to go into bankruptcy to begin with. And now that it’s coming out, it’s coming out with a very explicit series of blueprints that are turning it into one of the most unequal and under-served cities in the United States.

CM: Yeah, and when they brought in the emergency manager, Kevyn Orr—he was from the largest bankruptcy firm in the country. That’s what he does for a living; he’s a bankruptcy lawyer. So guess what he’s going to suggest the city goes through?

A couple of questions to what you were saying. Do you think these wealthy neighborhoods are overreacting? Because we had a gentleman on the show, an anthropologist by the name of Lowell Bergman. He wrote about how he was living in Detroit as an anthropologist, and I was telling him about my experience. I was born in Detroit and raised in East Detroit—right on the other side of Eight Mile from Detroit.

I was telling him how the impression that people have of Detroit, when you’re somebody who lives in the suburbs—and even the impression that people have who live outstate—is that at any moment you’re going to be shot or robbed or something horrible is going to happen to you in Detroit. And he said there’s a real exaggeration of how bad it is in Detroit, that a sense of fear in the city is not as great as people think it is.

Do you think that these private security firms might be an overreaction to the problems that Detroit is facing when it comes to policing?

LG: Well, you’re certainly right about the misconceptions of Detroit by people in the suburbs—largely white people, families who fled generations ago into the suburbs—as well as by people from across the country, people like myself who are not from Detroit. There is a huge media bias, and a misconception about what’s going on in the city.

I’m glad you brought it up, because I think it’s important to frame any conversation like this and not paint the city as some sort of dystopia. The reality is that hundreds of thousands of people live in the city, work in the city, raise their families in the city. The problem is that the city is vastly under-served, to the point that the United Nations came in recently and said there are serious human rights violations going on in this city, because the city has systematically cut off water to tens of thousands of people this year.

So it’s a tricky thing to talk about Detroit. As a journalist, I was very hesitant to do it until some organizers invited me to come up and tag along with the UN officials they invited in to investigate the water shutoffs. I was hesitant because it means navigating this space where there’s been so much propaganda about Detroit being an insecure place, being a dangerous place. And it’s quite clear that this propaganda is racially motivated. It’s incredibly racist and targeted.

So are the private security firms an overreaction to this racist propaganda? Probably. It’s also important to say that Detroit’s police department has very, very serious problems, which community organizers have been organizing against for a long time. They act with impunity in the same way that police across the country act with impunity. And because of the budget shortfalls, they’ve been posting average arrival times of 58 minutes on 911 calls.

It definitely changes the way people think about the police. Then there’s a huge number of residents who would never call the police to begin with, because the police kill people and act with impunity, largely against African-American residents.

The important thing that we need to understand about the private security is the way that it’s both a reaction to this fear and propaganda about residents in Detroit, and also part of increasing privatization of the city. That’s something that I was hearing from organizers over and over again. That what we’re seeing, coming out of the bankruptcy, is an increasing privatization—particularly of the downtown area, and the parks.

“People have lived in Detroit for generations, are very well-organized, and are rejecting these neoliberal policies.”

A lot of parks are now under public-private partnerships, being patrolled by private security guards. People are not permitted to exercise their First Amendment rights, even basic things like asking people to sign petitions. Private security guards are forcing people out, threatening people with arrest. This is in what are essentially public parks that the city’s tax dollars paid for.

This privatization is leading to an increasing exclusion of the African-American population—who has maintained this city for the last fifty years. They’re the ones who have built the city, who have kept the city running, who have kept it a viable place to live in the absence of functioning state power. And now we’re seeing privatization, and the exclusion of that very community.

We really need to understand what surveillance and private security means in the city right now. The overall blueprint is to pick some neighborhoods that continue to get services, and then shut services down in the vast majority of other neighborhoods, creating a very sharp two-tiered service structure.

So the majority of residents in the city of Detroit receive the most basic city services—some fire, some public police, some demolition of vacant properties, and essentially nothing else—and there are wealthier neighborhoods that can pay for extra services, and the surrounding white suburbs can pay for extra services. And this creates vast disparities of socioeconomic status—and also vast racial disparities, considering the population of Detroit versus the surrounding suburbs.

All of this is incredibly troubling, especially when this bankruptcy is being hailed in the international and national media as this great solution for the “problem” of Detroit.

CM: When I was reading your piece, it reminded me of the occupation of Iraq and how the Bush Administration was talking about how we need capitalism, we need to have a free and open market. They were talking about this neoliberal state that they wanted to build from scratch. They were going to tear down the old Iraqi state. There wasn’t going to be publicly owned gasoline or any type of public utilities. They were going to open up the market so all these foreign corporations could come in and “help them” with their infrastructure—that we bombed—so they could get back on their feet.

There was this whole idea that the entire country would be privatized. We’d finally have this wonderful experiment in privatization and neoliberalism, and this was going to be the framework for the rest of the Middle East, because we were going to see how well democracy operates within it.

Am I off-base in comparing what’s going on in Detroit to what happened with the Bush Administration’s economic policies and the way that they did “nation-building” in Iraq?

LG: I don’t think you’re off-base. But I don’t think it started with Iraq. We saw great efforts in the seventies to implement these types of neoliberal policies, especially in South America. We saw it in Chile, which now enjoys one of the most expensive and most unequal private education systems in the world. We see incredible class inequality in that country—and in a lot of countries where the IMF, the World Bank, the United States—and the “Chicago Boys”—pushed this neoliberal agenda.

Then they went over to try it in the Middle East, starting with Iraq—forcibly occupying the country, killing hundreds of thousands of people in order to implement this policy. Clearly, if we look at what’s going on over there, that policy failed. It was rejected by the people who live there.

And obviously they have tried to implement these types of blank-slate neoliberal policies here in the United States. I think you are on point to say that’s what they’re trying it in Detroit. The problem with trying it in Detroit—as was the problem with trying it in South America, as was the problem with trying to do it in the Middle East—is that people have lived in Detroit for generations, are very well-organized, and are rejecting these neoliberal policies.

When I was there, I spent two weeks doing reporting on the private policing and a long weekend following around the UN. I ran into dozens of community organizations—if not more—that are incredibly well-organized, all saying, “we’re not going to let this happen in our city.” Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, for example, is doing incredible work to fight against the neoliberal policy. People’s Water Board is a massive coalition of grassroots organizations that is fighting the mass water shutoffs and fighting for the human right to water.

There are dozens of organizations who are fighting the privatization of the school system. The public school system has been under emergency management for more than a decade now, and the school board is desperately trying to get the emergency manager out. They’ve been organizing for a very long time, but it’s very hard when the governor’s office in Michigan is doing these targeted racial attacks on all African-American cities in Michigan—not just Detroit.

So yes, there’s an attempt from the governor’s office, from Wall Street, and from the broader nation to turn Detroit into this blank-slate neoliberal project. That’s why national media shows simply vacant houses, burnt-out houses and burnt-out blocks: to put in our minds that people don’t live in Detroit, and so anything can be done there.

“We can put glitzy stadiums or nice Starbucks on the cover of the New York Times or the Washington Post, and say that Detroit has come back. But Detroit cannot be measured by what downtown looks like, when tens of thousands of people—when children—are living without water.”

That’s so far from the reality. After spending time with these activists, these community organizers who are fighting to keep Detroit a livable place, a place that respects human rights, and a place that honors the legacy of the people who have been living there for generations now, I think that this neoliberal project is probably not going to be successful. There are so many people organizing on the ground. It is being pushed incredibly hard by Snyder’s office; it is being pushed by Washington, by New York, by the White House. But I don’t think it’s going to be fully successful.

People outside of Detroit who don’t support this neoliberal agenda—who don’t support this white-washing and this erasure of what the city has been and who has actually built the city—need to figure out how to support the people on the ground in these grassroots organizations fighting to keep the city a livable place.

There’s a great effort to “repopulate” Detroit. But it’s clear what they mean by repopulation. And alongside this effort to repopulate Detroit, largely with white gentrifiers, there’s an effort to push everyone who has lived in Detroit for a long time, out of Detroit.

For example, there are these new “tax foreclosures.” Obviously there was a wave of bank-pursued foreclosures that began even earlier, before 2008. It really began in 2005-2006. Because the city was so awash in racially predatory mortgages—subprime mortgages that were specifically targeted at African Americans communities—that the crisis actually began much earlier. A quarter of a million people were pushed out between 2005 and 2010 through bank-pursued foreclosures. Now we’re seeing this wave of tax foreclosures where people are losing their houses because they’re behind on their taxes by sometimes only a thousand dollars.

The governor’s office has clearly decided, “we want specific people out, and we want new people to come in.” And that’s something that community groups are fighting very, very strongly, and people outside Detroit who object to that manner of massive displacement also need to figure out how to organize in solidarity and support the people in Detroit who are fighting against that.

CM: Laura, one last question for you, and it’s the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response. Is this kind of investment in Detroit, even though it makes “two Detroits,” even though it all goes into a downtown area that now has private security, that chases away unwanted people—is this at least “better than nothing?”

LG: That’s actually a question that I asked everybody. I went all across the city, and I interviewed people who had lived in downtown and had been pushed out; I interviewed people who recently arrived in downtown; I interviewed people in wealthy neighborhoods like Palmer Woods; I interviewed people in less wealthy neighborhoods; I interviewed people who were living without water; I interviewed people who were organizing against this neoliberal project in Detroit. And you get different answers wherever you go, because it depends on your position.

So when I was in Sherwood Forest, which is similar to Palmer Woods, I said, “people are saying that this is creating two Detroits that are so vastly unequal and so separate that we’re fulfilling the 1968 Kerner Commission. What do you think?” And people said, “well, honestly, maybe two Detroits is better than one, because the one we’ve had is just a poor city.” And I was very struck by that. But that was their opinion as somebody in one of the Detroits—the wealthier Detroit.

But when you speak to other people who are organizing against the water shutoffs, or who have had their water shut off, or people in unions that are facing pension cuts—I spoke to union workers in the Detroit sewage and water department, and they’ve had their water cut off because their wages are so low and the water bills are so high.

So you speak to them, and they say, “this is insane that we’re moving towards two separate and unequal Detroits, because the Detroit I live in is simply getting worse and worse and worse, and what does it matter to me if we have a thriving downtown?”

We have to reject this narrative that wealth trickles down, or that a glitzy downtown somehow benefits everybody. Economists have proven it’s wrong, sociologists have proven it’s wrong, anthropologists have proven it’s wrong, community organizers have proven it’s wrong, human rights activists have proven it’s wrong, and everybody’s lived experience has proven for the last fifty years that that narrative is false.

We can put glitzy stadiums or glitzy buildings or nice Starbucks on the cover of the New York Times or on the cover of the Washington Post, and say that Detroit has come back. But Detroit city cannot be measured as “coming back” by what a four-square-block downtown looks like, when tens of thousands of people—when children—are living without water.

Nobody is asking for free water in Detroit. What people are asking for in Detroit is to pay a water bill that is not two or three times higher than the national average. Not having their water cut off without their even being told. Not having their water being cut off when they’re current on their bill. Not having to send their kids to school at four or five o’clock in the morning because the schools open early in the winter—without turning the heat on—and turn the showers on in the gym because there are so many students who can’t shower in their houses.

This is an American city that has enough water. It has the ability to deliver water to all of its residents; it has the infrastructure to do so and the money to do so. When it’s cutting off water to its residents anyway, I don’t think we can say, “well, two Detroits is better than nothing.”

700,000 people live in Detroit, and all of them have the right to access to safe, potable drinking water, water to cook with, and water to shower with. If we’re not focused on that as a baseline of what we want out of a city, then I’m not really sure where our priorities lie as a society.

CM: Laura, it’s been great having you on the show again. Really a pleasure.

LG: Thanks so much for having me on.

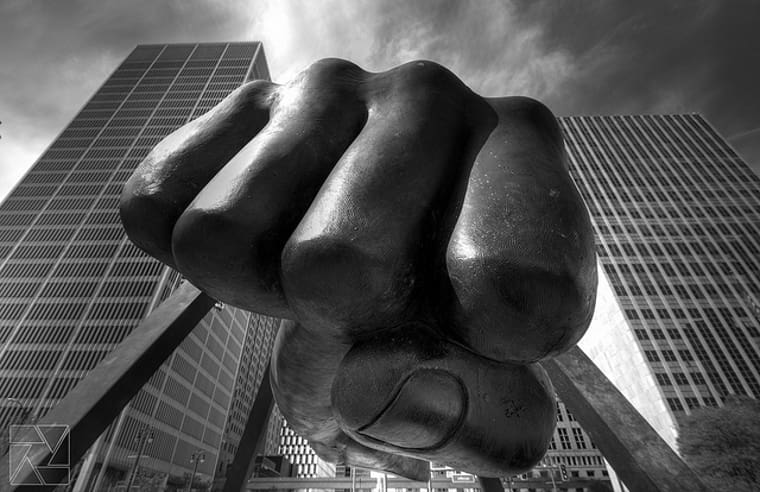

Featured Image: Kyle J. Schulz (Flickr)