AntiNote: The following is an extended excerpt of a radio interview, edited for readability. Transcribed and printed with permission. Listen to it in its entirety:

On 2 May 2015, host Chuck Mertz of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) spoke with activist Salma Kahale about the Syrian revolution—using that very term, in fact, which has so shamefully disappeared from many of our vocabularies when we talk about Syria.

As the conflict entered its fifth year two months ago, we posted on our Facebook page a compendium of articles—including several from our own archives—by activists who persist in using the word. These were our thoughts at the time:

It isn’t the Syrian Revolution that failed, we have failed. Failed to inform ourselves, to share the importance of the continuing Syrian Revolution and to stand in solidarity with it. One day we will recognize the legacy of a struggle for justice, freedom and self-determination that has very few equals throughout history. The heroes of the Syrian Revolution are well and alive and remain forever an inspiration for courage and resistance and humanity.

Today we salute all of those who struggle for freedom and justice and remember the 15 arrested schoolboys of Daraa who on March 6th 2011, inspired by the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia, sprayed the following words on the walls of their town and brought Spring to Syria.

“As-Shaab / Yoreed / Eskaat el nizam!”

(“The people want to topple the regime”)

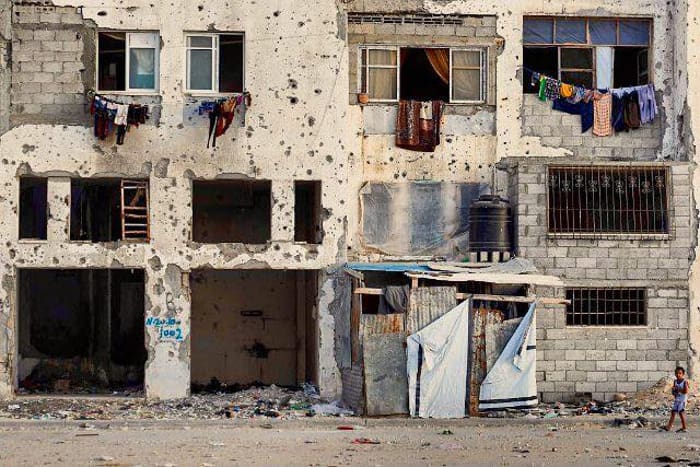

With this in mind, we have also interspersed in this interview a small selection of photographs by the Damascus-born journalist Rami Jarrah, whose Facebook and Instagram feeds are must-follows, as is the independent media organization he co-founded in Syria, ANA Press. He has recently been making stunning portraits of children in Aleppo, and even as his photographs have been attracting more and more attention, he has been unfailingly generous and kind in granting permission to use his work. Captions are also his.

Long Live the Syrian Revolution!

Chuck Mertz: There is a peace movement in Syria. A new coalition, involving tens of thousands of activists and dozens of organizations, has a plan to stop the bloodshed there.

Here to tell us about the possibility for peace in Syria, Salma Kahale is a spokesperson for Planet Syria and director of the Syrian NGO Dawlaty, which works with young nonviolent activists to enhance their engagement in democratic transition processes.

Good morning, Salma.

Salma Kahale: Good morning.

CM: It’s great to have you on our show.

Planet Syria is a new campaign representing a coalition of 85 groups, totaling 17,000 Syrians, who are demanding international pressure to end the fighting and immediate peace talks.

Why is this coalition so important? Why is it so important for these groups to come together? Does this represent some kind of change in the Syrian peace movement?

SK: It’s really important. Four years ago, when the revolution started and people started demanding freedom, justice, and dignity, there were a lot of movements. A lot of different groups were starting to form. For many years, people hadn’t spoken to each other. There was a lack of trust. There were informers. There were examples of people informing even within their own families. It takes a while for trust to build, and for small groups to form and then develop into bigger coalitions, and to speak honestly about their opinions and to form their opinions into actual strategies.

When the revolution started, the international demand was a transitional government to replace Assad. Of course, given that people hadn’t talked to each other in so long, and didn’t trust each other, this was an impossible demand.

But with time, people have been making an effort to go beyond the question of who’s going to take over, and focus on what we actually want and how we can come together to get our voices heard. No matter who’s at the table, we want to create pressure and make sure that the voices of civil society are heard. No matter who’s negotiating, they must know what civil society and communities in Syria want, and what they want a peace process to look like.

CM: I like that you call it “the revolution,” and you don’t call it the “Syrian civil war.” So many people who are watching what’s going on in Syria from the outside forget that this started as a revolution.

Not that the Arab Spring actually “worked” anywhere, but why didn’t the revolution in Syria work? Is it somehow indicative of the peace movement’s inability, up until now, to get together?

SK: For many of us the revolution is still a process, it’s still in progress. We’re still working towards justice and dignity and freedom. Of course the amount of bloodshed and repression, that the regime would come down this hard on people, that it was willing to go to such lengths to repress activists, was something that we didn’t anticipate.

Also, the regime has played on existing Islamist movements and groups, as well as fear of the Islamists, within Syria as well as outside, to amplify that threat and divert the revolution from one that was more national, let’s say, into a more religious one.

That was for many reasons. First of all, the regime, from day one, went around trying to warn people about “the Islamists” when there was no Islamist threat, creating fear among different groups. They released Islamist prisoners, but detained, tortured, and killed the leaders of the nonviolent movement.

Even when the violence and bombings by the regime started, their military would sometimes fly over areas that were controlled by ISIS, bypassing them, and hit areas where more moderate forces were operating.

There were many great groups, but it takes time to build a movement. It takes time to talk about what you want, and to form a coalition. Then there’s the lack of international support. The regime gets a lot of support, and Islamist groups get a lot of support—but these secular, small, nonviolent activist movements and groups didn’t get the same kind of support. That weakened their work as well as the revolution’s main demands and ideological drive.

CM: A lot of people say that the reason the Islamic State exists is simply because there was a power vacuum in the region. Others will point out that they are former members of the Iraqi military. But you seem to have said in your response just now that the Assad government was far more directly responsible for the rise of ISIS than just by creating a power vacuum.

How responsible do you think Assad is for the creation of the Islamic State?

SK: Quite responsible. The injustice, the impunity, the lack of accountability of the regime and its military has played a major role in driving people to them. But the regime also had a strategy, from the beginning, of trying to push the revolutionary movement to become more radical, more Islamicized.

They’d been monitoring Islamist groups for forty years. They knew them, because they were letting them into Iraq before. And when they came back into Syria they monitored them. So they knew exactly what they were doing when they set them free from their prisons, meanwhile cracking down on more moderate activists that provided an alternative to them.

They wanted to create this false binary for the international community. “It’s either us or people like ISIS, so you’d better back Assad. You’re going to get ISIS if you get rid of us. You can’t have a democracy in the Middle East, because look what you’re going to get.”

For many Syrians, the Assad regime and ISIS are two sides of the same coin. The choice is not one or the other. We believe that there is another choice, and that we can have freedom and democracy. We don’t have to just choose between extremists or a totalitarian regime.

CM: This argument comes up a lot when people here in the US talk about arming “moderate” Syrians. Are there moderate Syrians that the US should be arming in Syria?

SK: It’s not about arming certain groups and putting more arms into Syria. At this point what the international community can do, clearly, is stop the regime’s use of barrel bombs, which are creating the most civilian casualties. This is a very clear source of violence, and one that is harming mainly civilians.

They are indiscriminately bombarding schools, hospitals, and basic infrastructure, pushing whole populations to flee an area, and leaving safe havens for more radical groups to strengthen their positions in those cities. Rather than putting more arms into Syria, let’s stop one of the major causes of civilian death, which also then leads to radicalization.

If we can do that, maybe we can put pressure on the regime to negotiate in good faith. The regime has been coming to all of these negotiations with no pressure on them from the international community to actually give any concessions. There hasn’t been any kind of pressure on them. We need this kind of pressure from the international community in order to have meaningful peace talks. The point is not just to have peace talks.

The international community is unfortunately already involved in Syria. It’s not that this is just Syrians fighting amongst each other. There is a whole range of countries that are involved, in one way or another, on all sides of the conflict in Syria. They need to play a more constructive role to stop the violence and put pressure on the different sides to talk meaningfully.

CM: To you, what explains the rest of the world’s seeming lack of interest in ending the war in Syria?

SK: It’s difficult for me to say what the world is thinking. It depends on who you are speaking to. I think the reasons change. But of course experiences in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya have led people to be wary of any kind of involvement. That’s understandable. People need to be skeptical of their governments and the reasons they give for why they should be involved in any conflict.

But at the same time, that doesn’t mean they should absolutely reject any intervention of any sort. There is a consensus around the principle of the right to protect, which calls for the international community to step up and take a role when governments fail—or refuse—to protect their own civilians.

So while I think there are many reasons, and past experiences have made people wary of intervention, I think it’s important not to let that blind us to what is happening in Syria and to the responsibility the international community has to act in solidarity with the Syrian people.

CM: It would seem that a peace that could end the violence is impossible. How can you satisfy Assad, the rebels—all the rebels—plus the Islamic State, and the Kurds, not to mention the Turks, the Iranians, the Saudis, and the West?

SK: In different groups involved with Planet Syria, we believe that all sides of the Syrian conflict need to be involved in negotiations. But we also believe that there needs to be new leaders who have not committed human rights violations. Any peace needs to be a just peace that brings accountability with it.

We don’t have it sorted out in detail how that comes together. But what we do know is that the international community and the major actors also have an interest in ending the violence, and they have an interest in a stable Syria and in curbing the radical movements that are taking over different parts of the country and not just harming Syrian civilians—who are their first victims—but now also harming people around the world.

It’s in all of their interests to actually come together to stop the violence.

CM: I’m glad that you mentioned a stable Syria. Can we have a peace that keeps Syria as one singular country? How important is it to Syrians—and how important is it to Planet Syria—to keep one Syria together?

SK: I think it’s very important. Actually, I haven’t met any Syrians who think that we should break up the country. Syrians and Syrian activists are committed to the territorial integrity of Syria. Of course within that, there needs to be an acknowledgement of the rights of religious and ethnic minorities, and a need to create some sort of self-determination for groups—like Kurdish groups, for instance—within Syria and to provide for cultural and other rights, like language rights, for instance. That needs to be part of the new Syria.

To say that we can break up a country based on ethnicity—Syria is much more mixed than that. That’s one point. While there are areas where there is a large concentration of one ethnicity or another, it’s not so easy to draw lines and create five new countries. That hasn’t really worked very well in other places, either. We know of other experiences, and we are wary of these other experiences where the solution has been to harden religious and ethnic lines by creating governance systems based on them. We’re wary of further reinforcing these divisions among us.

What we need is something that guarantees people’s rights—religious and cultural rights, but also their rights as citizens. Because that is what will protect us all in the future, having rights as citizens; having religious and cultural freedoms but also political and civic freedoms.

CM: A spokesperson for your group has been quoted saying, “A few months ago a few Syrian grassroots groups surveyed 277 prominent nonviolent activists to find out what they thought needed to happen in order for the violence and extremism to end. There was overwhelming consensus on two issues when it comes to the Syrian war. First, the urgent need to stop barrel bombs and other weapons of indiscriminate killing. And second, the importance of engaging in genuine peace talks to reach a just political agreement.”

Why barrel bombs in particular? What is their impact on the ground in Syria? Why are you targeting those in particular as a step towards the end of violence in Syria?

SK: Barrel bombs are actually metal barrels, filled with shrapnel and explosives and thrown from helicopters. Helicopters usually fly at lower altitudes, but in order to avoid being hit by fire from the ground, these fly at much higher altitudes and throw these bombs out the side. These are not accurate weapons of war. These are messy weapons of war, and cheap weapons to build.

The regime has been using them more and more often, in order to punish areas where they have lost control. There are neighborhoods in Aleppo, for instance, that have been bombed by barrel bombs on a regular basis. Once, twice a day, sometimes more. And now that the government has lost control over the city of Idlib, it has been using barrel bombs there almost daily.

They mainly hit civilians. These aren’t precise weapons. They don’t hit military targets. They hit civilians. They hit hospitals. They hit schools. What they do is terrorize people. They cause people to be afraid of anything overhead. People are actually afraid of sunny days, because you get more barrel bombs on sunny days.

They destroy infrastructure. They destroy people’s ability to survive in their communities, and cause them to flee. And what happens when all these civilians flee, all these families flee—who is left? The more radical groups are strengthened by the fleeing of the civilian population.

The other thing is that the regime has been putting chlorine chemicals or gas into the barrel bombs more and more. When they agreed to dispose of chemical weapons, chlorine was not one of the weapons that was on the table. And now they use it—often—and people are afraid. I’ve even heard people say, “I hope if I die, I die by a regular barrel bomb.” They are so afraid of choking to death, of what a chemical attack would feel like.

This is a terrorization of the population. And this means that when the regime loses control of an area, the population isn’t able to set up proper alternative forms of governance. It’s very difficult to have talk of elections—even though there are a lot of different attempts to do that, and some good attempts. It becomes very difficult to have a voice of reason saying, “Let’s not take revenge. Let’s have processes; let’s have court cases. Let’s have some form of justice.”

It’s very difficult to do that when you’re being bombarded on a daily basis. Or, if you’re not being bombarded, that fear is constantly there. It makes it very difficult to build any stable institutions and real alternatives.

CM: Your group states that “the UN Security Council banned barrel bombs last year with a unanimous resolution which even the regime’s allies, Russia and China, supported. Yet still, Bashar al-Assad denies the existence of barrel bombs, as recently as last month in an interview with the BBC.”

What does that say about the ability of the outside world to have any impact on bringing peace to Syria? If we can’t stop Assad from dropping barrel bombs, how are we going to get him to discuss peace terms?

SK: It’s not a sign of what the international community can do—it shows what the international community at the moment is willing to do. There’s a lack of political will to stop the regime, to put more pressure on the regime’s allies. That is something that requires people around the world to mobilize and push their governments to act.

After ISIS started beheading journalists, American citizens, the international community mobilized quite quickly to bomb ISIS. When they wanted to come around a cause, they were able to. They were able to get arms, get an air force together, come up with the funds and the will they needed to act. But they were only acting on the symptoms of the problem. ISIS is only able to survive and flourish because of the injustice that is happening in Syria and other places in the region. If we don’t deal with that core problem, then we’re not going to get rid of ISIS.

There are the means. The international community can do something. But there needs to be pressure on decision-makers in order for them to realize that it’s not just about putting on a show for the American public. If the American public or other Western citizens are concerned about ISIS and the threat of terrorism, then they need to pressure their governments to actually look hard and act on the source of this terrorism, on the reasons that these groups are flourishing.

CM: Salma, one last question for you, and it’s what we call the Question from Hell: the questions we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response. What’s a better recruitment tool for the Islamic State? Is it their videos, or is it barrel bombs?

SK: Well, I think there are two things. One of them is barrel bombs and the injustice that’s happening in Syria and the lack of action around it. And the other one—and I’m sorry to say this—is the marginalization of young people in Western countries, where many of these foreign fighters are coming from. Many of them—especially in ISIS, especially their leadership—are not coming from Syria. These are young, disenfranchised people coming from different places in the world. That’s also something that needs to be looked at, but it’s not for me to talk about.

CM: Salma, I really appreciate you being on the show this morning. Thanks so much.

SK: Thank you.