Quitting, as an individual act of rebellion, remains just that. To be revolutionary it must be an action taken collectively. Do we have it in us?

by Antidote’s Ed Sutton

Getting Personal

Once again it has been a stretch since you, dear reader, have heard directly from our writers collective. As we begin to feel your eyes on us, and as the number of eyes grows, we have been grappling a little with insecurity. As such, this essay represents a petulant determination to ignore the imagined pressure to “drop something big” and simply stick to what we’re good at. Although we have confrontational ideas, we are bound somehow to voice them calmly and quietly (though not always), and we find value in ponderous reflection and even some touchy-feely self-examination. Isn’t that what we all wish more people would do?

The other thing that has kept us from contributing our own writing in the last several months has been the intervention of life itself. No one in our writers collective is a writer by trade—this would be a possibility in the post-capitalist utopia we are gunning for, but for the time being we have to scrape together a living in other ways. Since this is a common condition among activists, citizen journalists, and other supposed layabouts, it seems worthwhile to examine.

Come to think of it, the struggle to strike a “balance” between doing a job and doing what you want (or, put more romantically, living your ideals) is a common condition full stop. Approaching cliché territory, if not already sitting there with its feet up. But on the assumption that readers of Antidote will identify with and therefore forgive me, I’m going to commit two large social faux pas: complain about my job and tell you about a dream. It’s in service of a greater good, I swear.

Literally Immobilized

Like many other left commentators of late, including some we have featured on Antidote, I’ve been having issues with work lately. The concept of work. I’ve also been having issues at work. I concede the two may be related.

Nobody wants to hear this from me, though, least of all people who know what I do. I’ve always felt a little embarrassed telling people my line of work; I’ve only recently gotten out of the habit of shutting down inquiry by replying, “Manufacturing,” without elaboration when asked. I build musical instruments by hand in a tiny artisan workshop in Switzerland.

For those that smell some pride in that statement, you’re not wrong. I am passionate about my work, and, yes, proud of it. Beyond producing the basic and well-known feelings of satisfaction that come with creating something concrete and functional, assembling instruments that only resonate if the pieces hang together tension-free has also guided parts of my eternally-gestating philosophy on collective political action.

Considering this, my job should qualify for that all-too-rare designation as non-alienated labor. That is why I prefer not to talk about my work; I fear the resentment of comrades who are, like nearly everyone on the planet, alienated. But instead of being the exception that proves the rule, my “dream job” should serve as further evidence that capitalism really does ruin everything.

Still, with a recent display of rare expert diplomacy, my boss (and therefore you—be thankful) narrowly escaped a detailed accounting of my workplace grievances appearing here in black and white. Suffice it to say that as a result of his practiced strategies of devaluing my labor (to justify grindingly low pay, among other capitalist or authoritarian incentives to control), yes, unfortunately, I have become alienated. Passion I had for my work and the fulfilling connection I once felt to the products of my hands are gone.

It’s saddening. It has gotten bad enough recently that I have spent a lot of time, much more than is healthy or constructive, dwelling on it. Some of it near-catatonic, sprawled half-on and half-off my living room couch, staring at a corner of my ceiling, watching spiders lie in wait, hoping, hungry.

Straddling

There are other reasons for my paralysis, though, related to the cliché struggle I mentioned above between living one’s ideals and making a living. The same crisis of identity that comes along with, say, wanting to teach dance but having to work in a call center gets compounded, I have found, when one’s over-thinking (“critical analysis”) begins to isolate the deeper root causes of the daily insults and injustices produced and experienced at the call center. Anti-capitalists who participate in capitalism (and we all do) are bound to feel this tension, this sense of being in the wrong place all the time, even more acutely.

I think it’s just as common, though less talked about, for this tension to extend into anti-capitalist spaces as well, to the extent those exist. “Fitting in” is a learning process in both contexts, and we all have a foot (or at least a finger) in each. Which is tough when the two are so irreconcilable.

To put it flippantly: for my whole life I’ve had one foot in squaresville and the other in freakyland. This has always meant that the squares think I’m freaky and the freaks think I’m square—even if, in either case, they like me anyway.

This has some advantages, of course, when it comes to my ambition—nakedly displayed in this blog—to translate the customs and criticisms of the one world to and for the other, and to examine where they overlap. But it’s also dicey, because being regarded by freaks as a square or by squares as a freak can also be a good reason for either to keep their distance.

This means my ability to move, free and unsuspected, in either world—which would be important in getting to know either intimately—could be restricted, impeded or removed at any time. Or at least I’m terrified that it could be, whether that’s rational or not. This is a fear that is also commonplace, I recognize: the fear of being found out.

Could it be that the only way out of this existential discomfort is to commit entirely to one world and reject unequivocally the other? If so, we all know which one we would pick, I think. But who among us can do that?

Any of us, if all of us do. You might be surprised at how many “squares” end up joining us. You can count me among them if you like.

Want a post-work society? Stop working.

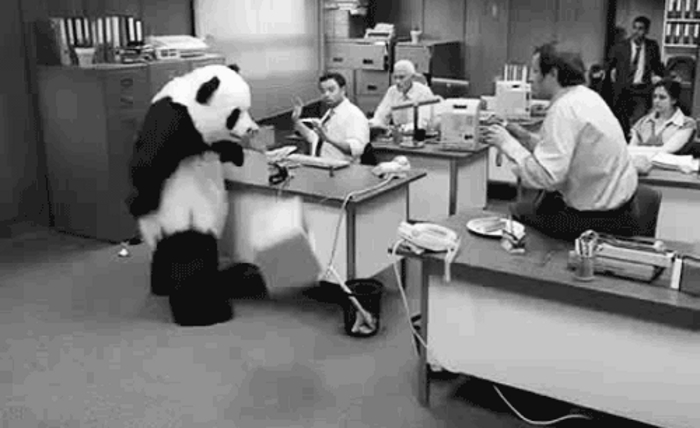

A general strike is typically regarded as the most radical possible intervention available to resist capitalist oppression. It is not! It is tame, flaccid, boring, reformist! A general strike has a beginning and an end. It assumes that one day, probably the next day, we will all go back to work. It accepts that the system will remain more or less intact and we will all resume along more or less the same trajectories as before, perhaps with some minor improvements that will quiet us back down for a time.

What we need is a general strike that never ends. Let’s all quit our jobs. At the same time. Forever.

Many reading this have likely had, at some point or another, the privilege of experiencing the euphoria of quitting. Whether it’s an abusive relationship, a school full of bullies, a soul-rending job, or even just a crappy band—the bigger the commitment, the higher the stakes, the better it feels just to say peace. In my experience, quitting can produce a near out-of-body experience that might last for days.

Imagine if everyone, or at least a hell of a lot of us, just quit—for whatever reason, but all at once. Everyone simultaneously experiencing themselves and the world around them with that heightened sense of self-worth and possibility, that weightlessness, that readiness. Everyone with that same sustaining rush of adrenaline. To harness that energy and perpetuate it through collective projects on our own terms—the collective projects we would be working on right now, if only we had the time and the guts…imagine what we could accomplish!

Combine that energy with the highs mentioned by many activists when they describe engaging in collective action and experiencing true solidarity for the first time. This stuff is real, and if we accept that feelings have political relevance (which I imagine you do if you have stuck with me this long as I exclaim about all these oh-so-important feels I’ve been having), perhaps we should explore crude ways to organize and “use” them revolutionarily. Our opponents have it figured out when it comes to fear and anger; let’s use euphoria.

A comrade explained to me recently one of the principles of political organizing that guides his work: that desperation and privation do not inherently produce revolutionary possibility in society the way many on the left seem to wish when we mutter sanguinely about the approaching global economic or ecological cataclysm. The cultivation and growth of revolutionary potential requires political space, which is reduced when people are totally fucked.

An exception proving this rule recently has been the Greek solidarity movement, described elsewhere in these pages, that is building revolutionary structures in the wreckage of a civil society stripped of nearly all its traditional economic and political power. If they can do it there, it seems like we ought to be able to manage something similar, and perhaps even more ambitious, in places where the political space for action is less constricted. And just imagine the political space that would open up on Everyone Quits Day.

I am only half joking. My work is idyllic and my life is safe and comfortable. I have a couch to collapse on and a living room to hide in. And yet I’m climbing up the walls. The vast majority of the alienated and persecuted laboring world has far more legitimate grounds to throw down. Maybe we are all just waiting for someone silly enough to propose it. I’ll take the hit. Let’s start looking at dates. It’s time to strike forever.