Transcribed from the 25 July 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“Whenever we see ourselves repeating a tactic nostalgically, whether it’s mass marches in the streets like in the sixties or occupying like in 2011, then we know we’re making a mistake.”

Chuck Mertz: Occupy Wall Street was a failure. Okay, it was a constructive failure. But are we looking at the end of protest as we know it? Let’s hope so. Here to tell us what we can learn from Occupy and the potential future of protest: Micah White, who is credited with being the co-creator and the only American creator of the original idea for the Occupy Wall Street protest.

An honor to have you on This is Hell!, Micah.

Micah White: Thank you for having me, Chuck.

CM: Micah’s new book The End of Protest: A New Playbook for the Revolution comes out next March. His writing will cover the future of activism, global social movements, the paradigms of protest, and the influence of media on the mental environment. Micah is the co-founder of Boutique Activist Consultancy, a social change consultancy specializing in impossible programs. Their motto is “We win lost causes.”

You are the co-creator of Occupy Wall Street, along with Kalle Lasn, who we had on the show a couple of times back in the twentieth century. Kalle wrote the classic Culture Jam, which was about the practice at the magazine he co-founded, Adbusters, where you worked as an editor. Adbusters says they are a “global network of artists, activists, writers, pranksters, students, educators, and entrepreneurs who want to advance the new social activist movements of the information age.”

You argue Occupy failed, but call it a constructive failure. We’ll get to that in a moment, but let’s start with the beginning of Occupy. Some people may not even know that Occupy was created by a couple of people at an anti-consumerist magazine in Vancouver.

So how did you and Kalle create Occupy Wall Street? And more to the point, what was your idea in creating it? Did you foresee what it was going to become?

MW: One of the reasons Occupy Wall Street worked so well is because very few people knew where it came from. It seemed to emerge spontaneously, all of a sudden. But remember that in 2010-2011, there were these uprisings happening; the Arab Spring was going on; there was an uprising in Tahrir Square in Cairo, where millions of people were gathering in the square and demanding that Mubarak step down. And then on May 15th of 2011 there was a Spanish uprising where citizens started going into their squares and holding general assemblies, where they started using consensual decisionmaking processes.

So Adbusters wrote a tactical briefing where we suggested, “Hey, everyone, let’s combine the model of the Egyptian uprising (go to a place of symbolic importance) with what’s happening in Spain (these general assemblies), and let’s take that to America and do that in Wall Street. Let’s occupy Wall Street and have general assemblies.

We made a surrealist poster of a ballerina dancing on the Wall Street bull. And we wrote a two-page tactical briefing explaining why this would be the next tactical breakthrough that could trigger a revolution.

The moment was so ripe that twenty-four hours after we sent it out to our email list and started posting it on the internet, it got taken up by people in New York City. It got taken up by a computer programmer named Justine Tunney, who started coding the Occupy Wall Street website that became the central hub. People in New York City took the idea and they ran with it. They started holding weekly meetings in Tompkins Square Park, and that’s how it unfolded.

CM: So this is the thing that I don’t understand: why did the media say this was a leaderless movement with no demands, when at any point, ABC, NBC, CBS, PBS, FOX, or CNN could have interviewed you or Kalle Lasn on TV? It would take thirty seconds of research to figure out that you and Kalle were behind this, because it goes right back to Adbusters magazine.

MW: About demands: the original tactical briefing that we wrote actually does have a demand. It said that we think Occupy Wall Street should demand that President Obama set up a presidential commission to investigate the influence of money on politics. That didn’t get taken up, because of the activist culture of New York City, which was pre-figurative anarchism. They rejected the use of demands.

But the second thing, about why we weren’t asked to do television, is that we refused that role. The simple answer is that Kalle and I made the decision to turn down all television interviews. We didn’t feel that we should accept them. Whenever journalists would get in touch with Adbusters about Occupy Wall Street, we would refer them to the local activists. We kind of stayed in the shadows intentionally, and the only real article that was written about Occupy Wall Street that interviewed both Kalle and I and revealed the origins was for the New Yorker. The New Yorker article is basically the definitive account of the origins of Occupy Wall Street.

CM: How much was New York City activism’s embrace of anarchism an obstacle to the success of Occupy Wall Street?

MW: I think the embrace of anarchism was good. But it was a specific kind of anarchism, the idea of pre-figurative anarchism: you don’t make demands of society, instead you try to create the society you want to live in. There was some magical thinking: we can set up this encampment in Wall Street and it will be the microcosm of the ideal society, and the bad society around us will crumble and everything will be great. That obviously turned out to be a failure.

The reason I call Occupy Wall Street a constructive failure is because it revealed our false assumptions about activism. It revealed the falseness of pre-figurative anarchism, and it revealed the falseness of ideas underpinning Adbusters’ approach, which was that if we can bring millions of people into the street making a large, unified demand, and if they are able to stay dignified under police repression, then the government would be forced to listen to them.

That’s not true. President Obama didn’t even mention Occupy Wall Street until after the Zuccotti camp was evicted, until the movement was defeated. It’s easy to blame other people, but we also have to blame ourselves. Occupy was a constructive failure because all contemporary breeds of activism were false; not just pre-figurative anarchism, but also this idea that mass spectacles in the streets are supposed to influence elected representatives.

CM: In one of your speeches that I watched online, you were talking about how tens of millions of people take to the streets in India and nothing changes; how millions around the world take to the streets in order to stop the Iraq War, and nothing changes.

The numbers of people in the street are supposed to motivate politicians; they see votes out there and they’re supposed to have an impact on their policy; they’re supposed to change policy. And as you argue, changing the law is really what a revolution is.

But we have the impression that this kind of protest works because—whether it’s true or not—millions of people went into the streets against the Vietnam War, and that’s what ended the Vietnam War.

So how much does the idea that the Vietnam War was ended by a mass popular uprising in the United States undermine the efficacy of today’s protest?

“I think that true activism is always something that is a little bit edgy. You ask someone to do something that’s a little bit scary. But when they do it and they display their courage, then other people start to lose their fear, and they start to do those things, and it becomes a spiral.”

MW: What happens in human history is that a new tactic will arrive, and it’ll suddenly unlock the passion and the anger and the desire for greater freedom among people. A perfect example is 1848. In 1848, there was a Europe-wide insurrection that toppled the king of France, spread to Germany and every country in Europe. One reason it happened was this new method of using barricades to lock down the urban streets in order to have protests. That use of barricades spread everywhere, and the authorities didn’t know how to respond.

But as soon as they figured out how to respond—which was by destroying the barricades with cannons—they ended the revolution across Europe within about a month. Ever since then, whenever barricades have been used (for example in the Paris Commune of 1871), they have failed.

The same thing happens with other tactics like mass marches. A great tactic only works once, and one of the lessons for contemporary activists is that we always need to protest in different ways. We should never protest the same way twice.

Same thing with occupying. Occupying was very effective for about two months. Police didn’t know how to deal with these encampments spreading all over the world so quickly. But as soon as they figured it out (with the Bloomberg model of using paramilitary police to forcefully evict the encampments), then all of the encampments were basically evicted within a week. And occupying never became effective again.

I think the greatest challenge for social movements is to be able to adapt and change in mid-course. Occupy started on September 17th, and Zuccotti Park was evicted on November 15th. So within two months it was obvious to people who were paying attention that encampments were basically over. But Occupy was not able to change, and on December 17th, they tried to occupy another space—and even since then, too, that idea has persisted.

It’s clearly very difficult for a movement to change course in that way. But we’re going to have to see social movements that adopt tactics and then abandon tactics when they stop being effective, in order to create new tactics. Whenever your approach relies exclusively on one tactic, you end up being defeated.

The international solidarity movement with Palestine experienced this because they had the idea that internationals wouldn’t be harmed by the Israeli military, and could get away with acts of nonviolent resistance. But then the Israeli military started harming international activists. So that tactic didn’t work.

Whenever we see ourselves repeating a tactic nostalgically, whether it’s mass marches in the streets like in the sixties or occupying like in 2011, then we know we’re making a mistake. The interesting thing about it, though, is that sometimes very old tactics can become useful again. Maybe building barricades would work with some tactical twist to it, because in a certain sense the authorities forget how to respond. But still, the larger point is that when we follow the script of protest, our protests are no longer effective. They become just part of the ritual, and even though they’re exciting, they’re not going to achieve the social change we want.

It’s a constant game. It’s an arms race, basically, between protesters and power. “The end of protest” doesn’t mean the absence of protest. The end of protest means the proliferation of ineffective protest.

CM: You’ve said, “For me, the main thing we need to see is activists abandoning a materialistic explanation of revolution—the idea that we need to put people in the streets—and starting to think about how to spread that kind of mood, how to make people see the world in fundamentally different ways. That’s about it. The future of activism is not about pressing our politicians through synchronized public spectacles.”

Do you believe that protest is far too geared toward having an impact on electoral democracy?

MW: I think that the next generation of social movements will be a hybrid between a social movement and a political party. It’ll be a kind of social movement that is able to win elections in multiple countries in order to carry out a unified global agenda. For example, imagine if SYRIZA didn’t just have the government of Greece but also won elections in Germany and was therefore, in effect, able to “negotiate with itself,” because of a united global movement. I think that electoral politics are still a key battleground for social movements, and I think that social movements will probably be able to defeat traditional electoral parties.

But one thing we learned during the Arab Spring was very important: that revolutions are actually caused by a change in mood within a society. The Arab Spring was triggered by someone setting themself on fire. And then more people started setting themselves on fire, which demonstrated a sudden loss of fear. They were willing to sacrifice themselves to demonstrate the injustices in society.

That fearlessness spread throughout the entire world. All of a sudden we were all swept up in this revolutionary mood, losing our fear. “I don’t care if I lose my job, I’m going to the encampment.” Revolutions are actually caused by a spiritual awakening that happens within people. And that’s not a material process. That’s a deep inner process.

What I’ve just described is the foundation of Adbusters’ approach to activism. When I used to work there, we talked constantly about “creating epiphanies” within people. That was our approach to activism, and I think that’s why we were able to spark Occupy Wall Street, because we did see it as an awakening within people.

Of course the challenge is to create an “awakening” within people that also translates into the ability to win elections in multiple countries and make complex decisions internationally.

“The defining defeat of democracy happened on Febraury 15th, 2003. On that day, the entire world, millions and millions of people, in every country in the world, went into the streets and protested against the Iraq War. They had one simple demand. No to the war. It did not stop the war. No government, no representative democracy listened to the protests.”

CM: Is fear not just the enemy of activism and protest? Is fear both an obstacle to activism as well as the fuel for activism?

MW: I think that’s a really excellent insight. There’s one notion of activism which says there is a ladder of engagement, and you need to lead people from the lowest, lamest levels of activism (like clicking links) to the highest levels of activism (like direct action). I think that approach is completely misguided. Instead it seems to me that what really triggers a revolutionary moment is that you ask people to do something that’s really scary.

For example with Occupy Wall Street, we said, “Hey, let’s camp in the middle of lower Manhattan!” Which is actually a terrifying thing to do. Sleeping on the streets in an urban area is not something that most people are comfortable with. That gave a lot of people butterflies in the belly, a little bit of fear. But when they saw other people doing it, all of a sudden they felt inspired. They lost their fear, and then it became contagious.

I think that true activism is always something that is a little bit edgy. You ask someone to do something that’s a little bit scary. But when they do it and they display their courage, then other people start to lose their fear, and they start to do those things, and it becomes a spiral.

At the same time, fear is a weapon that’s used against us. The most effective way to break street protests is just to brutally beat up protesters, because—we saw this in Oakland—the average person cannot witness police violence more than two or three times before they say, “I’m staying home.” It’s traumatizing to see people get beat up by police, to have sound grenades and tear gas fired at you. Most people will not—or cannot—deal with that more than a few times. And police know that. That’s why they use those techniques.

So fear is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, you want to use fear in order to motivate people, because when they experience the loss of it, it’s a tremendously uplifting experience. And on the other hand, we need to protect ourselves from being overexposed to fear and getting traumatized by the police.

CM: You have said, “Studies suggest that protests that use violence are more effective than those that do not. I think violence is effective, but only in the short term, because you end up developing a kind of organized structure that is easy for police to infiltrate. In the long run it is much better to develop nonviolent tactics that allow you to create a stable and lasting social movement.”

So do you believe that while violence may be more quickly and temporarily effective, it’s not as sustainable? Does violence work in the short run but is not a good continued strategy?

MW: This is one of the most controversial topics within contemporary activism. I get a lot of pushback for even suggesting that we think about violence at all. Because I believe in nonviolence, but I want to have a critical perspective on violence. What is its use, and what is it? A lot of people in the movement want to refuse that discussion completely.

For me, protest is a form of war. Clausewitz says that war is politics by other means, and I think we can say the same for protest. Protest is politics by other means. It’s a way of influencing or changing our laws and creating social change by unconventional means. Instead of lobbying, we protest in the streets, we use forms of direct action and pressure.

So it’s a form of war. But what kind of war is it? That’s really the question. In the seventies there was a study by William Gamson, called The Strategy of Social Protest, of protest movements between 1850 and 1940. He tried to figure out if there is anything in the data that determined their success or failure. And he saw that groups that used violence seemed to be more effective than groups that didn’t.

That was extremely controversial then, as it is now. In the 1970s, of course, they had all these urban guerilla movements going on. But looking back historically we’ve learned that groups that made violence one of their core organizing strategies completely failed. If we look at the experience of Che Guevara in Bolivia, he died trying to use the tactic of mobile guerilla units in a rural environment. It was a complete failure. If we look at the urban guerillas that were used by the Red Brigade in Germany or the experiences of Italy or Japan, which also developed their own kinds of leftist terrorism—all complete failures.

It’s not that we want to advocate violence. Instead, it seems that violence, if it’s effective, only seems to be effective in the short term. What we want to do is develop a much larger, broad-based movement that is able to adapt and change. Groups that pursue violence ultimately lose because they become so insular. The Red Brigade only had about twenty-five members, ever.

CM: You define revolution, as I was saying earlier, as making something legal illegal, or making something illegal legal. With Occupy, you wanted to change the law around money in politics. Is confronting the law itself—if that’s where revolution resides—the next step that protesters are too often unwilling to take? Is it the problem that they want change, but they want it within the law or the agreed upon rules of the game?

MW: There are different definitions of revolution that float around, and they really strain our concept of what we’re trying to achieve. One definition that’s been floating around for a long time is that a revolution is only what happened in 1917 in Russia, or what happened in Communist China. “Revolutions” are communist takeovers of the state.

I think that a broader definition is more helpful. That broader definition, like you said, is when we change the legal regime. When we make something that’s illegal legal or when we make something that’s legal illegal. But once you identify that’s really what a revolution is—a change in the legal regime—then you start to think, well, what are the ways in which that can happen?

One of the most important ways that can happen is by becoming the legislature, by becoming the sovereign who decides what the law is. That would be the ultimate revolution, if the people became the sovereign government. That would be democracy. If we restored democracy, and the people started to be able to dictate the laws that we live under, that would be a true revolution.

Activists have shied away from confronting these more difficult challenges in favor of a culture of dissent that celebrates protesting in the streets as an end in itself, because it feels good to march or whatever; they adopt a “radical” posture where liking certain ways of protest is similar to liking certain bands. It’s a cultural front.

“We need to stop thinking that mobilizing the ‘collective will’ somehow forces our representatives to listen. We need to realize that—for the last decade (or more)—that is no longer true. We need to base our actions on a whole different conception.”

CM: You talk about other concepts of protest; structuralism, for instance—that is, protest as a naturally occurring phenomenon. You mention the interpretation of the Arab Spring as being about rising food prices caused by climate change. In other words, there’s no need to actually organize protest; protests will naturally, organically happen when the public is confronted with hardship.

Is a structuralist approach bad for an activist’s ego, in that it implies that we are reacting not to some injustice but to the fact that we have less money or there has been some technological innovation?

MW: I love that question. There are basically four paradigms of activism that we operate under. The dominant paradigm is called voluntarism. Voluntarism thinks that human action is the most important determining factor in revolution. Revolutions happen when humans act. It often starts with the idea that “if only everyone would do x, then there would be a revolution.” That’s the core of voluntarism’s assumptions. And it feels great, because it celebrates human agency.

There’s another perspective, which is structuralism, the idea that revolutions are the result of forces outside of human control. This is really interesting, because there have been these studies that looked at food prices. It turns out that if the Food Price Index (a statistic compiled by the UN) reaches a certain point, uprisings seem to be much more likely. That point coincided with the Arab Spring. And its beginning to drop below that point again coincided with the decline of Occupy Wall Street and the global movement. Since that time, the Food Price Index has continued to decline; now it’s at the lowest level it’s been for several years. By this metric it seems like the revolution might be farther away than ever.

But I don’t believe in the structuralist approach either. I think there is another option, which is subjectivist: the idea that if we change our minds, then somehow we also change reality. And then there is a fourth option, which is that revolutions are actually a process outside of human control but non-materialist; they are divine interventions.

I think it’s a mixture of all four of these things, and all four are true. But coming back to structuralism: the most important insight about structuralism is that—and I think Engels and Marx understood this—if you’re not living in a revolutionary moment, or if your actions don’t create revolution, then it’s very liberating, because as an activist you are freed to act in any way that you want. If you have the same chance of having a revolution if you protest in the streets as if you plant a community garden or feed homeless people or create art, and each of those is equally protest, then you just do the one that expresses your inner self the most. That will be the most revolutionary behavior.

So I think structuralism actually liberates us from the voluntarist assumptions that make people think the only way to be a protester is to be an urban militant, which is a faulty notion.

CM: How much does representative democracy undermine the ability for protest to change the law?

MW: The defining defeat of democracy happened on Febraury 15th, 2003. On that day, the entire world, millions and millions of people, in every country in the world, went into the streets and protested against the Iraq War. They had one simple demand. “NO.” No to the war.

It did not stop the war. No government, no representative democracy listened to the protests. That, I think, was the defeat of our concept of democracy today.

We need to stop thinking that mobilizing the “collective will” somehow forces our representatives to listen. We need to realize that—for the last decade (or more)—that is no longer true. We need to base our actions on a whole different conception. Where I see us going now is towards this idea of a global democracy. There are a lot of challenges there, too; how are we going to make decisions as a global democratic movement? How would a social movement that won elections in multiple countries—how would local manifestations differ? How would it make decisions among the people? How would it avoid authoritarianism?

But opening up and solving those questions seems to be the most productive route, rather than maintaining nostalgic views that somehow, if we can rally the constituents, that elected representatives will listen and bend or even cave.

CM: Micah, I’ve got one last question for you. We do this with all of our guests: it’s the Question from Hell, the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response. Was the Tea Party a more effective social movement than Occupy Wall Street? And if so, what can the left learn from the right when it comes to social change?

MW: You’re throwing me in hot water here. I believe—and I advocated at the very beginning of Occupy Wall Street—that Occupy should have teamed up with the Tea Party. I believe that the 99% is neither wholly left nor wholly right, and that the leftist factionalism that refuses to create a coalition with the right is one of the things that’s holding us back.

Whether or not the Tea Party was more effective than Occupy, it just represents different organizing styles. At the beginning the Tea Party was a legitimate movement that became co-opted by corporate forces. Occupy in the beginning was a legitimate movement that also, less successfully, was co-opted by institutional activist forces. What’s really going on here is that there are millions of people all over the world, billions of people, who are demanding change and waking up, and we overemphasize how they express that dissent, and then we judge them. Are they using the words of the left or the words of the right?

I believe that a global coalition will always need to be some sort of blend of left and right, and that’s probably one of the least popular opinions on the left right now.

CM: Micah, I really appreciate you being on the show this week. Really a fantastic conversation.

MW: Thank you, Chuck, it was wonderful.

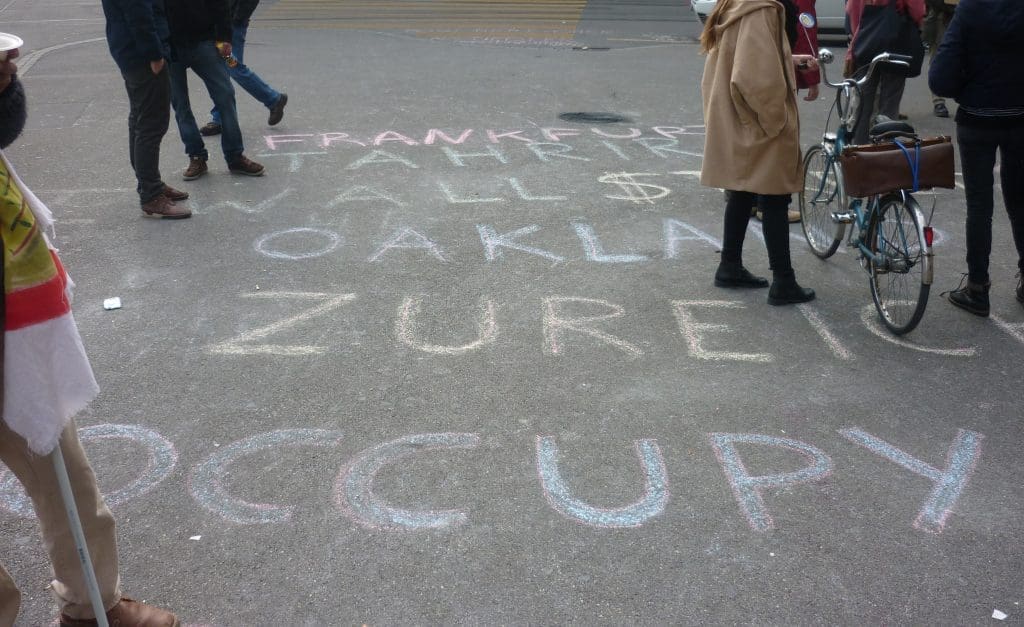

Featured Image: Paradeplatz, Zur(e)ich, 29 October 2011