Transcribed from the 29 August 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/221626829″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

“For a lot of parents, especially black and poor parents, the idea of choice is really a myth. The district is making these choices.”

Chuck Mertz: Hunger strikers are protesting the closing of a historic school on Chicago’s South Side. What kind of school would the community like to see in their neighborhood? And what are the chances in fighting back against massive public school closings, a strategy that’s probably coming to a city near you? And could this be a turning point in the battle over whether black lives matter?

Here to explain to us that students are not just digits in a financial formula: writer, research scholar, and artist Eve Ewing was a Chicago Public Schools teacher in the South Side community of Bronzeville, where she taught middle school. Eve wrote this week’s SevenScribes.com article Phantoms Playing Double-Dutch: Why the Fight for Dyett Is Bigger Than One Chicago School Closing.

Good morning, Eve.

Eve Ewing: Good morning, how are you doing?

CM: Good! It’s great to have you on our show.

It is now day thirteen of the hunger strike in front of Dyett High School. The hunger strikers are living on water, juice, and a fortified drink of some sort, according to WGN Channel 9 News. Mayor Emanuel argues, “I would remind everyone there are ten high schools within a mile of the school. There’s King College Prep. There are a lot of high schools in that area, and how do you talk about another one, or others, that are not at capacity?”

Why do you disagree with Rahm Emanuel? Why do you see this school as more important than he does?

EE: I would like to say that I’m surprised at how disingenuous the mayor is being when he talks about the other high schools in the area, but unfortunately I’m not. It’s very much in keeping with the normal bait-and-switch when we talk about closing schools in the city, especially schools that primarily serve African-American children.

In that quotation he even specifically mentioned King College Prep, which is a selective-enrollment high school. That means that students from across the city only get into King based on their seventh grade standardized test scores and their regular grades. It’s really disingenuous to talk about that like it’s a viable option.

Several of the other schools that the mayor may be referencing are schools that have specific admissions policies, for example a special health sciences program that’s nearby (where students, again, have to test in or get certain grades and be interested in careers in health care), a military academy, other vocational schools, and a school operated by the Academy for Urban School Leadership, Phillips High School.

Right now, if you were a student and your address was across the street from Dyett High School, you would be zoned into attending Phillips High School. And Phillips is operated, as I mentioned, by AUSL on an independent contract basis. It’s almost operating like a shadow district within Chicago Public Schools, and CPS is paying this organization—which was founded by Arne Duncan and venture capitalists—lots and lots of money to operate within the district.

And they have a really troubling history. Last year, [Chicago Public Radio station] WBEZ reported that Phillips suspended over half of their students over the course of the school year (they did a FOIA to get that data). That’s really troubling. It gives you an indication of what happens when you create a school that’s predicated on a real detachment between the community and the students and the folks serving them.

The way “turnaround school” policy works—again, invented by our Secretary of Education back when he was the CEO of the Chicago Public Schools—is that all the teachers in the school lose their jobs and they have an opportunity to reapply, but you bring in outside folks from a nonprofit to operate the school. And we see what happens there.

What the folks at Dyett are advocating for is an open-enrollment school, meaning that there isn’t a certain test-score cutoff; parents are not submitted to a special lottery, don’t have to fill out a special application, or do anything other than be a citizen of that community, and roll out of bed and walk a couple of blocks, and know that their children have access to a really high-quality, academically-focused education.

The bottom line is that the way we talk about “school choice” is often really misleading, because many students’ parents may or may not always be able to make a choice, depending on their personal situation.

CM: Let’s talk about that misleading debate, because I think that is at the core of so much of how the public sees and reacts to public school closings here in Chicago. Here is how the “choice” is framed: we can either pay tons of money to teachers (who are protected by a union, so they get more money than they would if they weren’t protected by a union) and spend all this money on all these schools…or, we can save the taxpayers money by closing down the inefficient or under-capacity schools and replacing them with privately operated schools that fill in the problem. Therefore, taxpayers are not paying for the schools anymore!

How much are these privately operated charter schools—that are not public schools—actually taxpayer-funded, and how much is the city actually saving through this process?

EE: There have been studies that pretty much dismiss the notion that we save money through these school closures. And if we look back at the reporting from 2012 and 2013, when the closing of fifty schools was happening in Chicago, we can see the discourse changing across the year, which is instructive.

First it was about cost savings; we’re going to save all this money! Then they realized through budget analyses that we actually weren’t going to save any money. So then it became about academic performance. And then it shifted to this idea of “building under-utilization.” All these buildings are “empty,” so we have to save money this way. I try to make my arguments based on more of a human rights perspective—but from a fiscal perspective, it is really questionable whether any money is saved from these actions.

And if we really want to take an economic rationale, it is prudent for us, in the long run, to create a city where all of our children receive a high-quality education. I would argue that the economic returns from that would far outweigh any short term benefits of closing a bunch of buildings, many of which are now sitting vacant. The district is still trying to figure out appropriate ways to repurpose a lot of these buildings.

“We have to create models for parental involvement that assume parents are an asset, and not an inconvenience, and that create ways for them to come into the school as meaningful participants and builders of community.”

But more importantly, these are not arguments we make when we’re talking about white children or affluent children in our cities. I think part of what you’re suggesting is how folks are really willing—more than willing—to fill in the blank of what they think these schools are like without ever once setting foot inside a school on the South Side (or, for many folks, any Chicago public school), and it’s very easy to fill in the blanks with easy stereotypes about how the schools are failing and the kids are suffering.

That’s not my experience, and that’s not the experience of many educators and folks that send their children to these schools all across the South Side. It’s really unfortunate that a lot of these policy decisions are being made, I would contend, based on stereotypes and not based on fact.

CM: How much do you think sensational stories about what takes place in inner city schools are the basis for people’s vision of what public education is like?

EE: Tremendously so. I would say it’s the whole thing. I will tell you, I have been physically struck by a student, in an accident in the middle of a fight at my school. It was not sensational. That student was a child who I knew from the time she was eleven years old and who I still keep in touch with as she is a young woman. She’s eighteen years old now and loves me and cares for me, and apologized.

When you are an adult going into a school district, your job is to be there to care for children who are imperfect human beings, who are doing their best to develop as people, as members of society, and as members of a community. Your job as an adult is not to be there for your own self-preservation or your own self-celebration. A lot of times folks write these reflections on their first year of teaching, and say things like, “The kids taught me more than I taught them!” Well, you should quit your job, because your job is to teach children.

Yes, it could sound sensational for me to say I was hit in the face by one of my students; I had this nice big bruise and everything. But we all have imperfect relationships with the human beings around us, who we understand to be imperfect creatures doing their best on a daily basis. And as a member of that school community myself, I understood the context around that student and why it happened, and I did not have an interest in prosecuting her or seeing her punished, as an eleven-year-old.

That is the difference we’re talking about when we’re talking about community-accountable schools. A community-accountable school is one in which every adult both inside and outside the building feels some kind of accountability and personal investment in the well-being of the children there.

Chicago is an imperfect city built on generation after generation of racism, segregation, and the systemic disenfranchisement of marginalized communities. That means we have many children who are suffering and experiencing a lot of challenges that they bring into the school building. So the question becomes, how do we as adults—not just the adults who work in that building, but the adults who are citizens of the city, who care about these kids—how do we take accountability for that? Do we suspend them? Or do we have some kind of restorative justice process for kids?

In the same way that our other relationships with our family members or our close friends are imperfect, children are imperfect too, but it’s our job to do our best with the kids that we have.

CM: You want a community school, but President Obama—and he’s not the only one; people on the right and on the left always talk about the problem with education being families not getting involved. That always seems to be the basis given for every problem that we have in schools.

So how can you have hopes for Dyett becoming a community school, when according to President Obama and so many other politicians, the problem is that families are not getting involved in their communities and the education process?

EE: We were talking a minute ago about stereotypes. I think that is really one of the most disturbing stereotypes out there. Folks who really do good work on family engagement would ask us the question of how we make our schools institutions built on the presumption that parents should feel welcome and should have every means necessary to participate as meaningful members of the community.

Instead, what we very often do is expect parents to bend over backwards based on the structures developed by the school. An example of that is school board meetings at ten-thirty a.m. on a weekday. How are parents or community members supposed to come? A friend from North Carolina told me that in their school district, they have those meetings after six p.m., because otherwise how can parents who work show up?

We might easily say, “Well, obviously parents don’t care—they’re not showing up to the school board meeting.” But what have we done to systemically make that really difficult? Jeanette Taylor-Ramann, who is one of the hunger strikers, has served on the local school council since she was nineteen years old. That is a prime example of a parent who is hyper-involved.

I think we have to create models for parental involvement that assume parents are an asset, and not an inconvenience, and that create ways for them to come into the school as meaningful participants and builders of community.

I did a research project that brought me to a school in northern California, a Native American school serving the Yurok reservation in northern California. They had a “Grandparents in the Classroom” program. These were grandparents in the community; they were elders. They would just come into the school and sit in the classroom, and sometimes they would read with a student, sometimes a student would read to them; sometimes they would sit there just going about their day, but doing it in the school instead of outside of the school. We can think about what kind of intergenerational bonds and creation of real, sustaining community relationships that that kind of arrangement suggests.

“Chicago is an imperfect city built on generation after generation of racism, segregation, and the systemic disenfranchisement of marginalized communities. We have many children who are suffering and experiencing a lot of challenges that they bring into the school building. How do we take accountability for that? Do we suspend them?”

But again, that’s the school being creative, instead of saying, “How come we didn’t have any grandparents show up at this PTA meeting at the time and place we set?” They looked at grandparents and thought about what they have to offer as members of the community, and worked from there, from a place of strength, rather than assuming that parents don’t love their kids, which is really the operating logic that goes on here.

CM: So you’re also very much against selective schooling. But doesn’t selective schooling give students the opportunity to find the best possible education that they can?

EE: I don’t know that I would say that I’m against selective schooling. I went to a selective-enrollment high school in Chicago, Northside College Prep, and I had a really wonderful schooling experience. I loved my teachers and my classmates. What I’m against is the ways benefits and advantages are tied to this selection.

I got into that school because I had good grades when I was twelve years old, and because I was a good tester. My life outcomes, in so many ways, have been shaped by the grades I got as a twelve-year-old child.

But when I was starting my sophomore year in high school, there were parents in Little Village who were on hunger strike just to have a school, period. So you know, I taught eighth grade. Teaching a group of eighth-grade students is really a lesson in heartbreak, because you have parents who have the hopes and dreams of their child, the person who they care about and love and have invested their whole heart and their whole life in, and they’re really concerned in Chicago that if their test scores aren’t good enough or their grades aren’t good enough, they’re not going to have access to a safe school—that their lives might actually be in danger.

That is unfair. When we talk about choice, we should talk about choice where there are equal opportunities available. If a student wants to go to a school where they study health sciences because that’s what they’re interested in, that’s fine. But that school also needs to be a safe school and a high-quality school.

There’s a lot of research now about how school choice actually operates. Often it is really based on the idea that parents are rational consumers, and they’re going to choose a school the way they would buy a stock. They’re going to do all this research and analysis and read through all these statistics. But there’s a really good book on this called Choosing Homes and Choosing Schools, edited by Annette Lareau and Kimberly Goyette, which shows that first among researchers’ findings is that districts don’t make this process of choice very easy for parents.

The district sends the parents letters; they are required to attend meetings that they can’t make or they’re not notified of; and in some instances their kids get zoned in schools that they did not select for them. For a lot of parents, especially black and poor parents, the idea of choice is really a myth. The district is making these choices.

And secondarily, it’s really easy to demonize parents who are people of color, who are poor. “Well, they’re not engaging in the choice process the way they’re supposed to.” But we’ve also found in other studies that white parents engage in school choice in a way that is often based on racism and stereotypes and not based on actual research either. White parents see the presence of black and latino children in a school as a negative indicator of safety and academic success, and studies show that they will actually enroll their children in a majority white school that has lower academic outcomes rather than put them in a majority student-of-color school that is doing better academically.

What we’re told we have is this idea of consumer choice and consumer decisionmaking. And what we’ve really got is just another mechanism for re-segregating and re-stratifying our schools. That’s really unfortunate.

CM: One last question for you, Eve, and it’s our Question from Hell, the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response. You went to public school in Chicago. So aren’t you proof Chicago Public Schools is doing a great job at educating students?

EE: I am proof that Chicago Public Schools does a great job of educating students who have already been pre-selected to be concentrated into one institution based on test scores that predict their academic success—and students who are willing to travel a really long distance, as I did to get to my school every single day.

When I was in high school at Northside College Prep, our principal, Dr. Lalley, sometimes got interviewed about how the school does so well. And he would say, “They come to us smart and we don’t mess them up.”

He was being brutally honest. That’s not a dig on the amazing high-quality education I received, or to say that there wasn’t tremendous hard work being done by those educators. But Mayor Daley really succeeded in creating a system that would do a lot of cherry-picking, enough to create a nice cherry orchard over here so all you need to do is bring the press conference to where all the cherry blossoms are.

Now I live in Boston. I live on the East Coast, and it’s totally changed my idea of what constitutes an elite education. Northside College Prep, the whole time I was there, was the number one most elite public high school in the city. But a lot of kids I went to high school with don’t have long term life outcomes that are reflective of that, and they are struggling middle-class and working-poor parents. They are facing student loan debt. Some work low-paid service positions. And even though it was a college prep school, people did not necessarily attend college afterward because of family financial constraints or other things like that.

I have friends that left Northside and went to Harvard, and I have friends that left Northside and worked at the grocery store. So even within the so-called gem of the system, we are still facing a larger systemic inequality. I had to move to the East Coast and learn more about schools like Exeter and Andover and other New York private schools—and what “elite education” means there—to realize that we’re still getting more or less bamboozled here.

It’s still a problem for everybody from top to bottom. The whole thing is broken.

CM: Eve, thank you very much for being on our show.

EE: It was my pleasure. Have a great weekend.

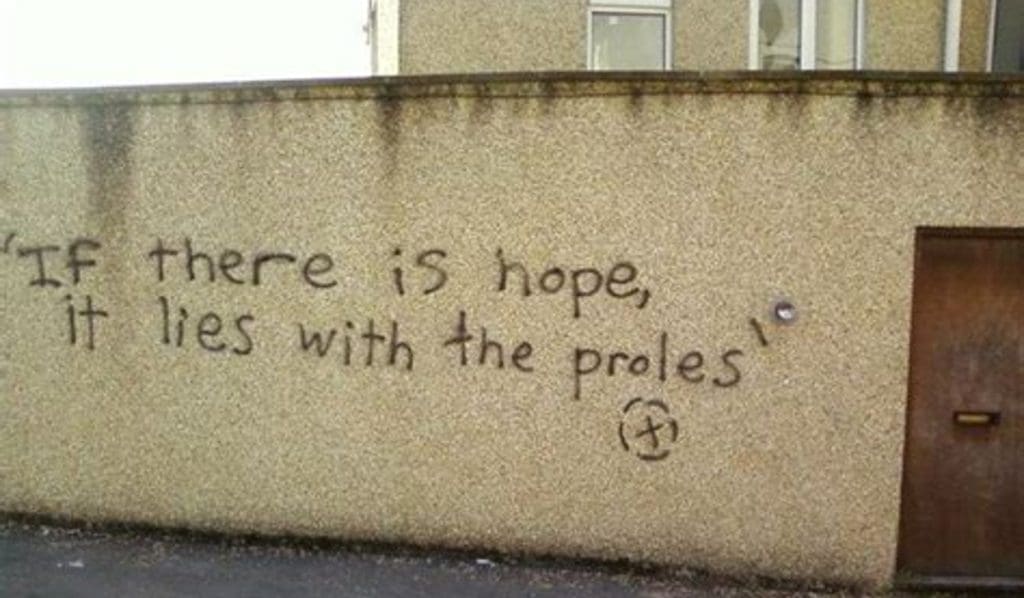

Featured image source: Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools