Transcribed from the 22 August 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Listen to the full interview:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/220646923″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

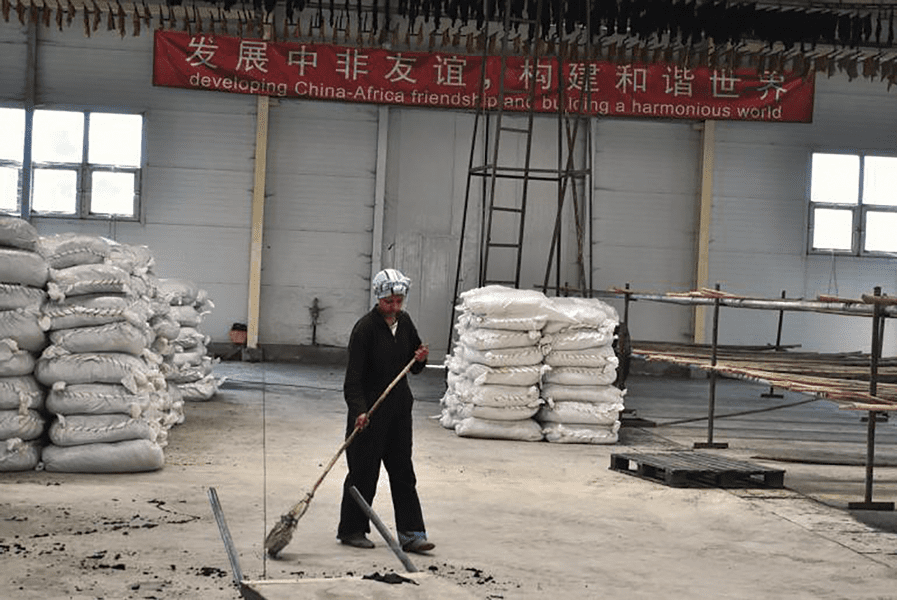

“A fine-tuned analysis gets at the nuance and gets away from both the scare story of ‘the New Scramble for Africa’ and the kumbaya story that because these companies are from the former colonial world, they’re going to act differently because they’re ‘nice.’”

Chuck Mertz: We are honored and delighted to have here in studio the Radical Pessimist himself, Kevan Harris. Kevan is here in Chicago attending the American Sociological Association’s annual meeting. Kevan is organizing a panel on Israel and historical comparative sociology, and presenting a paper on social welfare politics in the global south, which he co-wrote with Ben Scully. Kevan is a former producer here on This is Hell!, currently an assistant professor in the department of sociology at UCLA, former associate director of Mosovar Romani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies at Princeton University, and currently working on a book on post-revolutionary Iran.

But you’re on today to talk about China in Africa.

Kevan Harris: Yes. I was just on a two-and-a-half week trip to southern Africa. I spent a bit of time in Zambia, at an interesting conference called Southern Africa Beyond the West, where scholars, activists, and historians from all around southern Africa—not just South Africa, but places like Mozambique, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia—were talking about the new entry and influence of economic and political agents and powers outside of the West.

Particularly China, of course—people who read the news may have heard all about China in Africa. But it’s not just Chinese companies and Chinese politics entering African economies but also India, Brazil, and South Africa itself, which is a big economy whose capital flows north to various countries in Africa.

CM: In the seventies, when China was assisting the government of Angola, there was a big to-do here in the US about it because, you know, China’s invading! It was an extension of the Cold War into Africa.

How about now? Is there some sort of economic Cold War in Africa between the West and other agents?

KH: That’s a really good point to bring up. Many residents of different countries in Africa—not just Angola, but Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia—remember that in the 1970s and even the late sixties, Chinese aid and engineers came to southern Africa and were building infrastructure. Zambia, for example, which has a well-known copper industry, is a landlocked country, and the only way to get the copper to export was through Tanzania. So the Chinese helped to fund a railroad back in the 1970s, in the Maoist period, from Zambia to Tanzania. That railroad is still there today, and it’s used by the copper industry.

So while some people may think this is a new thing, many Africans remember that experience and they have a different perspective on South-South economic relations.

CM: One of the narratives that we always hear here in the US is that China works with horrible people like the Sudanese president who is wanted on charges by the International Criminal Court, whereas we, at least, have more strings attached.

Still, we have had Mike Hudson on the show talking about how the World Bank doesn’t do any oversight in giving funds to a nation either, as far as it being corrupt as an organization, when they are doing these megaprojects. But we’re in the US, and we “do a better job.” We “vet more.”

Is that the case? Are there fewer strings attached to getting funding for projects from China?

KH: There are two big stories that anybody who reads at all on this issue will probably encounter online or in the print media. One story goes like this: China is engaging in the new “Scramble for Africa.” The Scramble for Africa was when all the European colonial powers in the late nineteenth century started carving up Africa and taking its resources for themselves. Then, of course, there were African independence movements in the twentieth century. Now, new capital and companies and power from China and a few other parts of the former “Third World” are entering into the new Scramble. Meaning, same as the old boss.

That’s one story you read a lot, including people on the left who see capital as capital, no matter who’s touching it—it’s always the same type of capitalism.

But there’s another story, a competing narrative, that one also reads on the left, which is that this is actually something very new: a sort of South-South or Third World-to-Third World solidarity going on, a new type of economic exchange. Perhaps because of a different set of strings attached (or maybe even no strings attached), the entry of China, Brazil, India, and others in sub-Saharan Africa is leading to a different type of exchange than the old colonial exchange.

These are big, broad brushstrokes. And, as in anything, you can find examples of both in sub-Saharan Africa. The examples that we often read about in the news are about how China will do business with Sudan or Zimbabwe when the Europeans have not (even trying to cut off economic ties to these countries). And that’s true.

But whether it props up the state is still a question. “Propping up” might not be the best term. Certainly, China doesn’t care, particularly in places like Sudan, what the government actually acts like. And one could say the same thing about America’s realpolitik in a lot of Africa and the Middle East as well. It’s not like they’re better or lesser angels.

One distinction that we can make I got from my colleague at UCLA, a wonderful sociologist named Ching Kwan Lee, who spent the last seven years going to Zambia every summer and spending time in the mining and construction industries, looking at how companies from China, India, South Africa, and other places acted differently in these two different sectors.

She got frustrated by the big, broad coverage of these subjects by journalists who parachute in, talk to a few Chinese small merchants, and think that they know what Chinese capitalism in Africa is like. That’s including former New York Times reporters and plenty of other people. She spent a lot of time, and she has an interesting argument, and we posted a portion of her new book on our website, called The Specter of Global China.

She says some companies coming from parts of the former Third World in Africa act like any other type of company: they’re profit maximizers, and they’re beholden to their shareholders, including in the mining sector. So they push down wages, they treat workers poorly. They’re not any different than a company listed on the London Stock Exchange or the New York Stock Exchange. And in that sense, capitalism is capitalism, and it doesn’t make any difference.

“Africa is not just this blank slate and these big companies are coming in and buying up land and kicking out people. There are politics going on.”

But she also found another type of company with a different type of management logic, and a different type of capitalist logic. These were state companies coming out of China. She said that these companies have interests other than simply profit maximization, because they are very large state-owned companies that are part of a Chinese national development policy.

For example, in the copper industry, a South African company just cares about the price of copper, because for them copper is just a commodity that they want to sell on the market. It doesn’t matter if it’s copper or it’s widgets. But for a Chinese state-owned company, they actually need copper for consumption back in China. So they treat the copper sector very differently than a South African company listed on the London Stock Exchange. They care about long term investment. They don’t want to hire and fire workers at will, because they want skilled workers to stay in the industry to keep it less volatile.

She noticed that, for particular types of companies coming out of China (and probably some other places) that are linked to the state, the effects of that in terms of how they deal with the political situation and the labor situation is different. It’s a very fine-tuned analysis which I think gets at the nuance and away from both the big scare story of “the new Scramble for Africa,” of “neocolonialism and neo-imperialism with Chinese characteristics” as well as the kumbaya story that because these companies are from the former colonial world, they’re going to act differently because they’re “nice.”

One other thing I want to point out: this conference I was at in Zambia also had a presentation by Patrick Bond, who you’ve had on the show a few times. Very smart guy. He’s from Alabama and he went to Johns Hopkins University. He was a student of David Harvey’s. He’s been in South Africa as an intellectual/activist/scholar for a long time. But when he sees capital, he sees capital. He doesn’t see any difference, and he was very skeptical of all these new companies from other parts of the world other than Europe and the United States coming into southern Africa.

We had an interesting discussion at the conference. But some of the southern African historians other than Patrick Bond—people from Zambia, people from Zimbabwe—were saying something I don’t think Patrick was picking up on: that for them, there is a difference when it’s a company or a political intervention by a non-European state. For them, because there is a racial, ethnic, civilizational difference, it’s important.

As a final example, one hundred years ago, when the Japanese beat the Russians in the Russian-Japanese war, that was celebrated all around Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, because finally a non-European power had beaten a European power in war. Even though the Japanese were doing all kinds of nasty things, it was symbolically important for countries that were either still under colonialism or had just become independent. I know in Iran they became very interested in Japanese history the minute Japan beat the Russians in 1905.

That kind of symbolic example is going on again today. Take Angola, which finally exited a civil war and has a big oil boom: there’s all kinds of money flowing through; there’s some corruption, but there are a lot of new people taking part in an economy for the first time in their life, being linked up with other companies from around the world. For them, seeing someone who’s not from Europe actually starting a company, managing a big expansion, and engaging with them (not necessarily on equal terms), can mean something different.

I think people like Patrick Bond—who say capitalism is as capitalism does, and wherever it is, it’s exactly the same, and that’s all the analysis that’s needed—miss out on that perspective.

CM: But does the difference in motivation among some state companies in China—their focus being based more on what’s best for the entirety of the Chinese economy instead of just that company’s bottom line—is it that a distinction without a difference?

KH: They still have to make money. State-owned enterprises in China are not loss-leaders. These companies, for thirty years, have been forced to make money. It’s not like a sinkhole or a slush fund for the Chinese state.

However, the fact that they are state-owned enterprises means they have a different management strategy. Because the priority is not simply profit maximization—they probably make a little bit less than other private companies—for them the things that they’re engaging in, whether it’s mineral procurement or infrastructure development, serve a long term political goal for the Chinese government.

Now, what does that mean for Africans? This is interesting, speaking of the so-called “propping up” argument. In the case of Zambia, there was a change in government a few years ago; a new party was elected in Zambia. Part of that election revolved around the issue of resource nationalism. Meaning that people in Zambia—just like people in Iran, people in Venezuela, and people in lots of places that have resources—think that other countries are taking their resources and they’re not getting compensated for it at a fair and just price.

That’s a political issue, and it’s going on all around the world right now. So there was a big upswell, and in a relatively democratic election, an opposition candidate and party was elected. And then, out of that political upsurge from below—from Zambians mobilizing—the state then renegotiated with all the companies working in the copper industry.

Of course, the companies linked to the London Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange howled and screamed about paying more taxes or attempts to enforce labor regulations. The companies that didn’t protest were the Chinese state-owned companies. Because they had long term plans. So they accepted the tax hike.

Not all Chinese companies. We can’t conflate them all. But the point is that Africa is not just this blank slate and these big companies are coming in and buying up land and kicking out people. There are politics going on. So we have to look at how political opportunities are opening or closing in these different countries.

In a place with a one-party state like Sudan, you’re going to get a different outcome than in a relatively democratic society where politics and pressure from below can force the state to act and try to negotiate a better deal with these new economic interests.

“Neoliberalism becomes this covering term that doesn’t explain, it obfuscates. It hides what’s going on. We lose the ability to understand variation, and to see change as it’s happening.”

CM: How much would we over-romanticize the situation by thinking, “Finally, the Global South is giving colonialism the big Fuck You?”

KH: That’s a romantic perspective. I have been sympathetic to that perspective in the past, and I probably was overly romantic myself. It’s nice to be romantic once in a while, I’ve been told. That being said, the last ten to fifteen years of high economic growth in a lot of the Global South has been based on an unsustainable commodity boom—a lot of it driven by the growth in China.

That’s coming to an end. I don’t know if people are paying attention to what’s going on in China right now, but they’re having a little bit of a problem. The boom of the last ten years is coming to an end, but it was a boom, so it created feelings of goodwill. Everybody was growing at the same time. The North was suffering from the economic crisis; the South was doing well. It was easy to make that romantic argument.

Now, when economic growth is declining, and there’s a bit more of what looks like a zero-sum game going on, I wouldn’t expect that romantic view to be maintained. However, there is also the argument that when there’s more than one buyer in any kind of market, then it’s better; the seller will do better. In geopolitics and in global economics, I don’t see why it’s a bad thing when it’s not just the Europeans or the Americans coming, but there are also Chinese, Indians, and Brazilians knocking on the door and giving offers.

Some would say, well, that’s just more capitalism, but again: situation by situation it’s different. It can help on the ground because it becomes a seller’s market. I think that holds no matter what is going to happen in the next five or ten years.

CM: You know, if neoliberalism disappeared, Henry Giroux wouldn’t have a job. The best thing about neoliberalism is that Henry Giroux gets to write book after book after book. Similarly, Michael Klare has been writing about resource wars for twenty years. Resource wars, resource wars, resource wars.

Is the future of Africa the ultimate Michael Klare resource war that he’s been predicting for so long?

KH: Some of these things are broken records. One has to remember that when a concept becomes currency in activist debates and in politics (a word like neoliberalism, for example), it starts to lose its value for helping understanding the world. People might be shocked that I’m saying that, but frankly I think the term neoliberalism is explaining less and less about what is going on in the 21st century.

It’s a pejorative. No one ever calls themselves a neoliberal. It’s the N-word. You throw it at somebody else. Lots of so-called smart people are using this word all the time; they think it explains everything. They have what I would call the “blob” theory of neoliberalism: that neoliberalism is this type of capitalism that whenever it touches anything, that becomes neoliberal too.

So they start looking, and anything going on in the world, whether it’s new welfare policies in Brazil or China or India, or new activism in any part of the world that somehow might be tied to the state, they say, “well, because it’s touched the market or it’s linked to something else, it’s neoliberalism.” Everything connected is neoliberal.

It becomes this covering term that doesn’t explain, it obfuscates. It hides what’s going on. We lose the ability to understand variation, and the ability to see change as it’s happening. We’ll wake up one day and we might be in a different world, but we never had a term to talk about it.

As for “resource wars,” there’s an old school of thought, going back to late nineteenth century analyses of the economy—mirrored today in Pepe Escobar’s “Pipelineistan” concept—that sees the world through resource flows. And I mean, look, that does explain a lot of politics and economic change over the long, long term. But the problem with the “resource wars” analysis is that you look at a map of Africa and all you see are bauxite, cobalt. You see the map of a whole continent through what’s in the ground, and not through the political institutions and the people who live on that land.

They might not have a lot of power, or they might have power that changes over time, but they’re not power-less. I’m not celebrating—some people say we’ve got to celebrate that people resist. I don’t know. People resist all the time. They don’t win. A romanticization of resistance is also a trope on the left that I’m becoming tired of. People who resist tend to lose; I’m sure they’re not celebrating after they lose.

That being said, the “resource wars” story is a little bit too clean. It ignores the politics on the ground, and it closes off chances—even a rare chance—that there could be a different type of political arrangement there. Lots of Africa is not at war right now. And with this commodity boom—we can say it’s unsustainable, and it was, but it did change the politics in a lot of African countries, a lot of them for the better.