Transcribed from the 21 November 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“The question is, looking at this new robotic economy: what do robots buy? And the answer to that question is, obviously: not much.”

Chuck Mertz: Technology will be the solution to all our problems, and it’s inevitable: our future is one that will be a perfect world where robots do all our work—freeing all of us to be, well, servants to robots. Here to tell us why technology may not have the great fix for all of humanity’s challenges, social critic Curtis White, author of We Robots: Staying Human in the Age of Big Data.

Thanks for being on This is Hell!, Curtis.

Curtis White: Glad to be here.

CM: Advances in technology are the practical application of scientific advances, put into the hands of the public consumer so they can employ that new technology and in some way improve their lives, maybe by providing convenience, or information, or connectivity to coworkers and family.

Is our embrace of technology and willingness to adapt to it—and even let it take over aspects of our lives—not because of our faith in technology, but because of our faith in science? Do we have too much faith in science, and we misapply that faith to technology?

CW: Well, I don’t frame it in terms of faith, but what you’re speaking of is the consequence of stories that we’re told, and that we consent to. The book isn’t so much about robots or technology as such—I have no particular opposition to the existence of robots or technology. What I do have a problem with is self-interested and dishonest stories told to us by people from various sectors of the economy, by certain environmentalists, by STEM education activists, etcetera.

Those stories, it seems to me, ask us to consent to a certain kind of social vision that has pretty obvious victims.

CM: Is this uniquely American? And does it reveal something to us about US culture that we don’t pay attention to these victims?

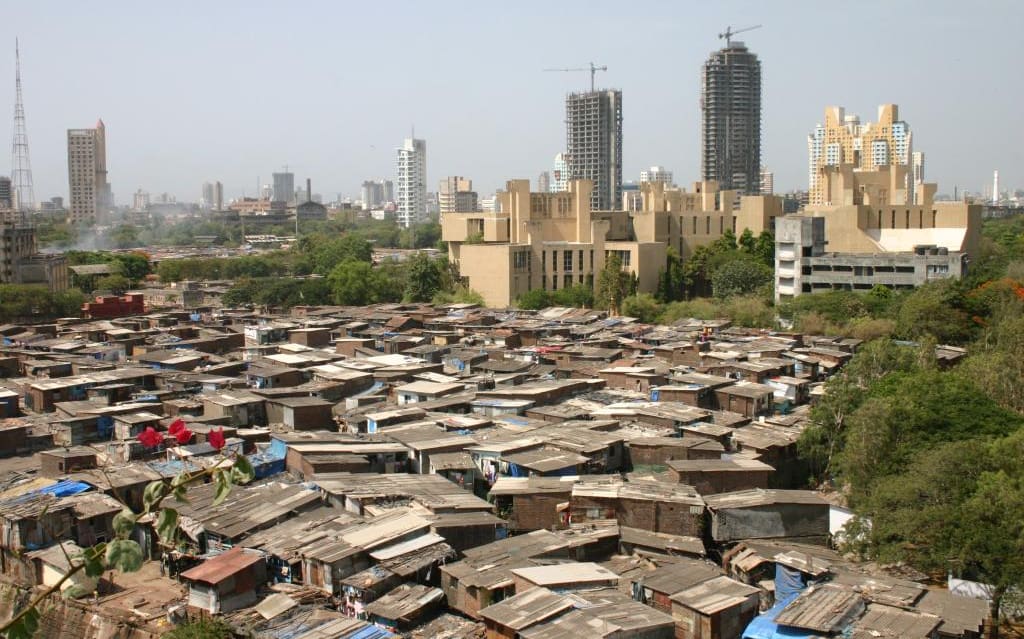

CW: One of the main focuses of the book is on a close reading of a book by the libertarian economist Tyler Cowen, Average is Over, that was in a way the zeitgeist book of 2014. And you’ll see what I mean by “victims” when I’m done describing his central argument in that book. Cowen argues for a new kind of social structure—a new class division, if you will. He says that in the future (although I think you’ll recognize this reality as very much like the present) there will be three classes.

The top class of high-earners will be people who can work with what he calls “intelligent machines,” i.e. robots and computers. That would be about the top ten to fifteen percent of the economy.

The second class, or the middle class, if you will, is what I call the “entourage economy,” and he argues that the function of this middle class is to make the upper class feel better about itself. Life coaches, massage therapists, chefs who cook the food in fancy restaurants, even university professors are to become part of this class of people who make the rich feel better. So university professors are no longer scholars: they become what Tyler Cowen calls “motivators.”

Motivate to what? I can’t quite say.

At any rate, the bottom class—which is enormous, about half the country, is essentially irrelevant. One old source of relevance for this class is gone: labor doesn’t figure in this class structure at all anymore. Cowen’s advice for this bottom class is that if they can’t afford the rent in desirable places like San Francisco and Seattle, where the techies live, then they should move to places where the rents are affordable, i.e. Texas. And while they’re in Texas, they should rent tiny homes, something between 400 and 600 square feet, and if their budget is squeezed, they should eat canned beans. Goya canned beans, to be specific.

Whenever I describe this “new” class structure, people listening to me probably think I’m making it up. But that is a very literal rendering of Cowen’s description of the economy of the future.

CM: How aware do you think people are of that potential for an economy of the future? It seems like everybody is going headlong into things like Uber or AirBnB and all these “sharing economies.”

CW: That’s one thing about this economy of the future that Cowen is seeing: it is basically for high-end consumption, for people in the top fifty percent of the country—and especially the top ten to fifteen percent of the country who have the luxury of these jobs with intelligent machines.

But obviously there is the bottom half of this class structure that doesn’t take part in AirBnB vacations or rides with Uber. They don’t have any contact with that culture. Cowen’s vision for this class of people is that they should be provided with free municipal WiFi so they can stay home in their tiny box in Texas eating Goya canned beans and watching Hulu.

CM: You write, “This story is being told and repeated by Cowen and others in order to create a sense of inevitability. We are also being told that there is nothing unjust about the world universal robots will bring, because it will reward the most deserving among us: the talented, the intelligent, the well-educated, and the creative who are capable of working with robots. In short, the robotic economy of the future is coming, and there’s nothing you can do about it, nor should you want to, because it is just.

“Yes, there will be winners and losers, but that’s the American way, the entrepreneurial spirit: ‘Stand on your own two feet,’ ‘To the winner go the spoils,’ and the rest of the hoary folktales of our winner-takes-all society. Folktales or not, we are asked to consent to them and accept yet another version of what 16th century philosopher Étienne de la Boétie first called ‘voluntary servitude.’”

Is the story so effective on us because those who accept its inevitability do not realize it’s voluntary servitude? Or are we aware of it and don’t care as long as it provides the potential for convenience?

CW: That’s a very good question. I think that most of us are certainly aware. There is evidence of an awareness at a very popular level, and even among the techies—the people who are (in theory, at least) benefiting most from this new social arrangement.

But it’s also, I argue, a powerless gesture. This understanding has no way of expressing itself except as resignation.

Certainly the people who have been consigned to the great class of the irrelevant are becoming ever more aware, especially as more and more members of the former white collar middle class get driven down into that lower class of the irrelevant. Since the recession the story in newspapers all over the country has been white collar management losing their positions during the downturn, and then being unable to come back into the economy at anything like the level that they were at before.

CM: How much do you think that 2008 financial collapse either provoked or promoted the “robotification” of the economy?

CW: That certainly was one consequence of the recession. It was well-reported on in the standard media: companies were investing in new technology, computerization and robotization, and there were lots of stories about that: of a factory that formerly employed this many people now basically being run by a few people running around and checking on the computer systems, making sure all the apps are working.

And of course it also had consequences in terms of employment and income for an awful lot of people. One of the most stunning statistics that I’ve seen recently has been in the most recent reports from the IRS on income for 2014. Of all people reporting to the IRS—in other words, filing taxes—forty percent reported earning less than $25,000 a year. And when you add the area between $25,000 and $50,000 it goes to over sixty percent of the population that is living a very precarious life. That’s actually a term that is used now: the precariat.

That is a really revealing statistic, especially remembering that this number is among people who were doing well enough to actually report income. Then start adding in the permanently discouraged, the unemployed, people in prisons. It becomes a stunningly huge number.

CM: You write, “As we know well enough, there is no shortage of evidence that this economy of the future is not only coming, but already here. Take the poor travel agent rendered irrelevant in the age of Expedia: Jamaica’s giant tourist warehouses and the Caribbean’s cruise ship metropoles now fill up by themselves.”

These apps, these sites, this software is doing more than just enhancing our leisure and making things more convenient for us—the technology is actually taking over. The robots are taking over. They’re taking over jobs.

How sustainable is an economy and a culture that outsources all work to robots and dedicates its entire culture and existence to maintaining, upgrading, and inventing new robots? How likely is a world where we all serve the robots meant to serve us?

“In Buddhism, the three poisons that create suffering are greed, anger, and delusion. Are the people who benefit from the distorted economy, from the self-perpetuating machine of capitalism, greedy? Are they angry? Are they deluded? Many of them certainly are those things.”

CW: At present it seems extremely likely. But I would caution against the use of the word “us.” Because there is no “us.” The technology economy we’re describing—taken as a whole— is for a very defined portion of the population.

So there’s that. But economists—and fairly conventional economists like Larry Summers—are beginning to weigh in about this, with the idea of “secular stagnation.” Secular stagnation, for Summers, means that there is nothing in particular driving the stagnation, there is nothing driving the diminishment of income for a lot of people. It’s just the new state of normal.

Summers’ argument—and I don’t usually quote Summers in approving ways—is essentially that the problem with the economy right now is that it’s under-consuming. There’s a lack of demand. And that lack of demand is a function of the absence of people with money in their pockets.

So the question is, looking at this new robotic economy: what do robots buy? The answer to that question is, obviously: not much. As technology and robotics replace more and more jobs, most of them formerly middle class jobs, where is the demand for the goods that the economy now can produce more efficiently? Where is that demand going to come from?

For some economists, the only answer is a minimum guaranteed income. In other words, the state has to find a way to sustain this economy by giving money away to people in order to create demand, so that people go out and spend money. One of the great symptoms of the recession is the way it put formerly really healthy entities like Walmart and shopping malls into deep trouble. Walmart is in trouble because its demographic is being increasingly impoverished. The people who would shop at Walmart because there is cheap stuff to be had there have been driven down to a point where they can’t even shop at Walmart or Kmart anymore.

CM: We’ve had a lot of listeners sending us emails about the concept of a basic income guarantee. We’ve had past guests discuss it on our show. In your opinion, would a basic income guarantee allow us to live with robots more easily? Is that the evolutionary step that we could take?

CW: All I can do, not being an economist myself, is point to some of the logic and remedies of more liberal left-leaning economists— not people like Tyler Cowen, who doesn’t seem to be particularly worried about whether the bottom half of the population can buy anything or not. There’s a really great website on economics called Pieria, where they have very articulately pursued this question of guaranteed minimum income, and say it’s really the only feasible way to address the problem of under-consumption. You’ve got to put money in people’s pockets.

But given the puritanical way that people in this country, especially in the Republican Party, think about the ethical merits of income (you’ve got to go out there and work hard, etcetera), this strikes me as a non-starter in this culture.

CM: You write, “Even scientists will have to adjust. Because of the complexity of the quantum universe, the science of the future will not be a realm for science heroes like Newton and Einstein, but for machine science, an elaborate bureaucracy in which, as Cowen says, ‘no one understands the equations. Like the drones in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, they may not even be able to understand the bureaucratic machines in which they work.’”

Do people like Cowen want the future to be Brazil? Is that their goal? And to what extent does the public know that’s what many economists want?

CW: It’s really hard for me to get inside the brain of someone like Cowen, and figure out even a little bit about how he thinks. I mean, he describes himself as libertarian. It’s impossible for me to understand exactly how that kind of mind works. It seems callous to me. This American Gothic attitude towards virtue: “It’s a tough world out there, it’s a jungle, but you’ve got to go out there and do the best you can.” I just don’t get how an intelligent, well-educated person can buy into that kind of moral baloney.

CM: You write, “These workers have found themselves in the discouraging position of having to compete with high school kids and underclass minorities for jobs flipping burgers at Wendy’s, or competing with philosophy PhDs and the latest arrivals from Somalia to drive a taxi. Unfortunately, in the Uber Era, neither philosopher, Somali, nor economic refugee will find long term refuge driving a hack.

“In other words, those fortunate enough to survive the seismic disruptions of the robot economy are, smartphones in hand, perfectly capable of getting around town without a taxi. Meanwhile, there go thousands of working class jobs, along with attendant dreams of middle class security.

“All this suffering has been well-documented. Its main function, now, is to provide anecdotal evidence of our recent recession, and we all feel the pain of the displaced and the dispossessed, because it’s pretty obvious that there but for the grace of God we go.”

Why do we go against our own best interests? Are we that incapable of realizing that something providing convenience now may also be against our long term best self-interest?

CW: Well. In Buddhism, the three poisons that create suffering are greed, anger, and delusion. And I think it’s fairly safe to say, in more secular terms, that those three things are at work. I would add that capitalism as a structure has become—maybe always has been—a self-perpetuating machine. Are the people who benefit from the self-perpetuating machine greedy? Are they angry? Are they deluded? Many of them, the people who really benefit from this distorted economy, certainly are those things. So yeah. I don’t know. You’re depressing me with my own thinking.

CM: There’s nothing new to the fear of losing our jobs to machines, but in the past those machines created jobs themselves, lots of jobs. Today they do not produce any jobs. Is our unwillingness to challenge the narrative of the inevitability of techno-plutocracy and techno-rationality due to what we may consider exaggerated fears of machines, in the past, taking our jobs?

CW: There is that luddite narrative still floating around to a degree. It’s very hard to say if it’s just an old fear that we haven’t overcome. Speaking of unwillingness, I would point out how unwilling the tech-driven economy of the last twenty years (and into the future) is to acknowledge in a fair and thoughtful way the damage that it does. That’s just not part of their narrative.

A good example of this is another storyteller, probably the original storyteller for this stuff, Steve Jobs. Jobs’ narrative about Apple was that it was going to be the opposite of big, bad, totalitarian IBM, that Apple’s roots were in the counterculture and in Zen Buddhism, and that his goal was to “think different.” Three decades later, people look at that narrative a lot more skeptically, but it’s a good example of the importance, for them, of narratives that are basically deceiving.

One of the ideas that informs most of my work is the old saying from the left: “Capitalism understands that it will have enemies. But if it must have enemies, it will create them itself and in its own image.” That is what Jobs’ Apple myth was about. If the counterculture and Zen are oppositional forces to corporate money-making, then the corporations (and Apple in particular in this case) will simply have to recreate them in its own image. Which it has successfully done.

“Finding other traditions and lineages in our own history can allow us to tell counter-stories, to narrate our world in ways that don’t go along with—that resist, that refuse—these dominant narratives, which are really just a pastiche of poorly-told stories that have horrible effects on people.”

Another chapter in the book is about Buddhism specifically—the techno-Buddha, the Buddha-Bot, as I call it. It won’t be news to your listeners that there’s a “mindfulness” fad surging across the country, especially through corporate programs about stress reduction. Google, with its Search Inside Yourself institute and its Wisdom.2 conference that it holds ever year (and that it invites people like Arianna Huffington to—she’s become a big cheerleader for this mindfulness thing), takes the oppositional potential of Buddhism—something that has its own integrity, a moral integrity—and hands it over to neuroscientists, essentially. They’re saying that Buddhism and meditation are mostly about understanding how the brain works, and understanding how the brain works through meditation can have great benefits for corporate employees. You can reduce their stress levels, and make them more productive.

CM: You’re also critical of the over-reliance of people pursuing an education in the STEM fields. What’s wrong with focusing so much on trying to find technical solutions to our problems?

CW: Again, my interest is really in the stories that we’re being told. The STEM story is coming on hard and fast, and every time I talk to educators about it, they’re pulling their hair out because so much emphasis, especially from President Obama, is on the idea that STEM is necessary to get one of these well-paying jobs that Tyler Cowen talks about.

But that’s not sufficient, really, especially for science journalists like Michael Schermer, who writes for Scientific American. It’s not sufficient to say that there’s a pragmatic reason for studying STEM disciplines. It’s also important to say that there’s something justified about it because science is superior to all other forms of knowledge. Certainly art, philosophy, and obviously religion.

So I take a couple of his columns and I analyze them closely, and reveal that they are actually pay stubs of preconceived notions, presuppositions, and really faulty logic. My point is that the putative reasonableness of STEM advocates is really just a flimsy front. Their claim is that they’re “reasonable.” But if you look carefully at the things they actually say, it’s fairly easy to show that, quite a ways from being reasonable (whatever that even means; what is reason after all? They don’t seem to question that), they’re flawed logically.

These narratives that we tend to buy into so passively don’t stand up to any kind of close analysis.

CM: Let’s talk about another one of those narratives. What do we miss in this rise of the techno-plutocracy when we do not realize that it is a choice, not a force of nature that cannot be stopped? We had the same kind of discussion about globalization; people just said it was inevitable, we had no choice.

CW: It’s a narrative that assumes “the economy” isn’t something that is daily created and re-created, but rather that it is something like a force of nature. This is fairly common among economists of all stripes: to refer to some thing called “the economy” as if that were something coherent you could say.

I have no idea what they mean when they say “the economy.” There is no economy as such. But this creature that they’ve invented, the economy, allows them to talk in a way that makes us think, “Oh, the economy is going to do this now, I guess we just have to adjust.” But it’s just another story, another piece of ideology that we’re asked to consent to.

And we do. But there is a positive side of the coin. The question is about finding other traditions and lineages in our own history that allow us to tell counter-stories, allow us to narrate our world in ways that don’t go along with—that resist, that refuse—these dominant narratives, which are really just a pastiche of poorly-told stories that have horrible effects on people. Many people. Most people.

CM: One last question for you, Curtis, and it’s the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience might hate the response. You write, “In spite of these disturbing issues, the work of Cowen and others including David Brooks is being treated in the media as if it were an appendix to the soothsaying of Nostradamus. Is this prognostication true or false? Will it come to pass or not?

“Others are claiming that, whether it is true or not, it is reality. For David Brooks, those who will suffer most will be those who lack the discipline and the motivation to adjust to ‘reality,’ never mind that all the self-discipline in the world won’t get them any closer to jobs that don’t exist, and never mind that many people are in fact re-training by enrolling in public universities, community colleges, and private vocational colleges, but all many of them are getting for their efforts is student debt piled on top of their joblessness.

“The economy Cowen imagines is not a meritocracy, let alone a ‘hyper-meritocracy.’ It is a caste system.”

So my Question from Hell for you is: Can this really be stopped with counter-narratives? It would seem that the narratives being embraced right now are so false that they should be easy to undermine. If counter-narratives haven’t undone them yet, can they, actually?

CW: Whether or not counter-narratives come to flourish again will depend an awful lot upon conditions on the ground, as they say. To what degree will our present course drive us towards extreme forms of both environmental and economic challenge?

The most diabolic thing about what Cowen proposes is that it isolates people so they don’t have a way of organizing and challenging, creating their own narratives. Labor unions continue to have their own brand of socialistic narrative. But it is sotto voce in this postulation of an economic future that they’re trying to imagine a world without labor. Get rid of the labor class altogether, because they’re a drag on profits and they’re a pain in the neck.

So there’s that. But what keeps me hopeful that counter-narratives are possible is that I’ve seen it. I grew up in the Bay Area and lived in San Francisco in the late sixties and early seventies; I grew up basically in a working class suburb of San Francisco. In high school and college I witnessed this crazy, wonderful, energetic reality grow up around me that said, We’re not taking part in that culture that we were born into. We’re going to do something else so why don’t you join us? I went screaming happily into their embrace. So I’ve seen counter-narratives flourish in our culture in the fairly recent past.

And forms of countercultural resistance continue to be a part of our culture in the present. I look especially at the impact of indie music and bands like Radiohead and Sufjan Stevens and Björk. I think that is hopeful, because an awful lot of people are drawn to it. And it certainly isn’t conventional.

In my last two books I have tried to focus on the tradition of romanticism. My argument is basically that romanticism lives. It’s still with us. I think of romanticism as a social movement that found a way of refusing the dominant culture—the dominant class structure, the dominant roles into which people were being forced—and found a way to flee that through art. Romanticism, for me, was not primarily an aesthetic movement, it was a social movement first. And it still is.

CM: Curtis, thank you so much for being on our show today.

CW: It was a great pleasure.