Any Place For Me

Two Stranded Refugees’ Tales

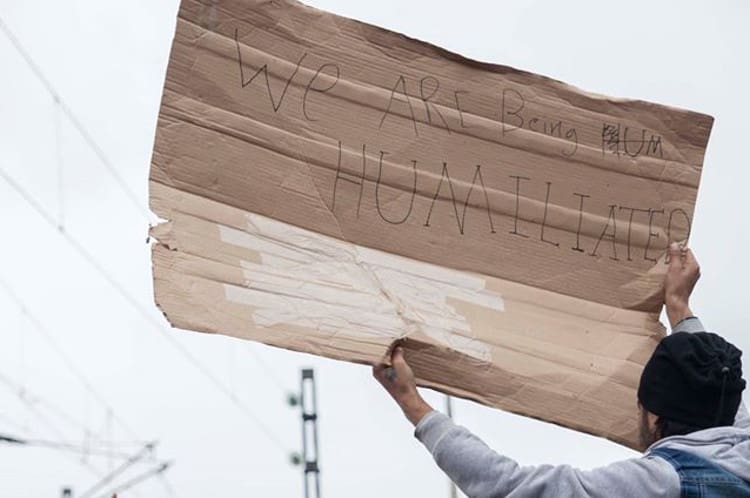

AntiNote: The news from the Greek-Macedonian border over the last few months, and especially the last couple of days, has been a devastating illustration of the real material effects that racist policies of “deterrence,” detention, and control have on real human people. Unfortunately, Idomeni is not the only place people are getting stuck struggling in life-threatening limbo because of the clenching spasms of a fickle, opaque bureaucratic border apparatus.

Serbian authorities are pushing people back into Bulgaria, Croatian and Slovenian authorities are pushing people back into Serbia, Austrian authorities are pushing people back into Slovenia and Croatia, and every Western European destination country is deporting people (this is nothing new) to wherever they can get away with, either through the Dublin Regulation or by declaring an asylum-seeker’s home country “safe.”

It goes without saying that the European Council’s stated goal of “rapidly stemming migration flows” is unattainable. Hardening borders, inventing discriminatory regulations, and criminalizing both travelers and those who help them—with the explicit intent of making conditions notoriously miserable—will not reduce the numbers of arrivals. Frontex even acknowledges this. So this violence and trauma being perpetrated on desperate and already traumatized people is literally senseless.

Senseless is the only word that really describes the damaging “institutional processes” that the two speakers featured in this article have been subjected to. Viviana has made it to Germany from Syria; I. has gotten stuck in Croatia on his long journey from Afghanistan. Both escaped one nightmare only to enter another. Viviana’s account is reprinted from the blog of the International Women’s Space (Berlin); I.’s appeared on the Facebook page of the independent aid organization Are You Syrious? as recorded by an AYS activist. Each has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s listen to them.

“The office manager decided to throw me out of the camp and put me on the streets, at night.”

Viviana, a Syrian refugee, tells of her first few months in Germany

21 February 2016 (original post)

I arrived in Germany on the second of December, 2015. When I arrived, I went to Lübeck. It is a very nice city. I lived in Lübeck for five days, in a camp, and after five days, when I went to the office manager to do my paper, he told me I must go back to Berlin, because I had a transfer to Berlin. I accepted, and went to take my bag and everything, and I am ready to go to Berlin. I arrive in Berlin at 4:30 p.m. and I don’t find any place to go, because Lageso is closed. I ask in Lageso, what can I do? Someone tells me I have to go to a basketball hall to stay the night, and in the morning I can come back to Lageso.

And I go the basketball hall and ask them to sleep there, in this place. He tells me “Yes, you can do it,” and I stay for the night—but actually it is so bad to sleep in this situation, because we don’t have a good bed to sleep on, and the situation in the basketball hall is bad; it is so dirty, and there were rats. I couldn’t sleep. I stayed awake the whole night, and at six in the morning I went to Lageso to do my paper. When I get to Lageso and finish my paper, the translator woman tells me I must go to a city near Frankfurt-Oder. She gave me a train ticket to Frankfurt-Oder, and I went to Frankfurt-Oder. After six hours I arrive to this new place in Germany.

I am surprised when I arrive in the new place, because everything is not good. The security office keeps all the people who arrive outside, in the cold weather. We asked security, please, can we go inside, but they don’t accept. And I asked the security man, please, I need water because I want to take my medicine, and he also doesn’t accept to give me water to take my medicine.

After one hour, he comes to take me to a room. I asked him if it was my room. He tells me, “No, it is for everybody here. If you don’t want to sleep there, you can leave and go to any hotel, if you have fifty Euro.” I don’t accept the situation, but I must wait for this night.

And I go into the room and see about twenty people there, men and women. Many from Afghanistan, Iran. Nobody speaks Arabic in this room. And also the mattresses in the room are so dirty. You can’t imagine what happened with these mattresses. It is so dirty. Some people make—I am sorry about my words—pipi in the mattresses. And the toilet also is so, so dirty. I can’t go to the toilet.

I stay the night, and at seven in the morning I go the office and tell him I want to have my own room, or another room. He tells me, “We don’t have enough space here, you must return to Berlin.” I accept to return to Berlin, and ask the security man, please can you give me a ticket to return to Berlin because I don’t have money. He tells me, “It is not my responsibility. You must leave now.” I don’t have money. I say it many times, please, I don’t have money to return to Berlin, can you give me something? A ticket or anything to help me return to Berlin. He doesn’t accept to help me. I cry. I don’t know what to do.

When I cry and shout, he tells me I can go to another office and ask for some help. I go to the other office and tell the woman inside, please help me, I don’t have money to return to Berlin. First they don’t accept to give me any help, but after I cried and shouted, she accepted to give me water to take my medicine, and to give me a ticket to return to Berlin.

I come back to Berlin and go to another camp there, but I don’t find a place for me. Then I ask in another camp, please, I need a place to stay. The office manager tells me, “We don’t have space right now, you must wait.” I tell her, please, I don’t have anywhere to go. I will live in the streets if you don’t accept me in this camp. She tells me, “Maybe I can help you, and take you to my parents’ to stay for the weekend, and on Monday you can come back to Lageso and wait.” I say thank you so much, and I go with her to her parents’ and stay the weekend with her parents. And on Monday I go back to Lageso and ask them about any place for me.

I stayed all day in Lageso, from 7.30 a.m. to 9.30 p.m. Finally, a bus arrived Lageso to take everybody to a new camp at the Wiesenstrasse—which is another basketball hall, not a camp. We live together, men and women, in the same place. We don’t have anything in between us, we just live together, men and women. I stayed there three days, sleeping with my clothes on. We don’t have a place to take a shower, because we don’t have any privacy in the shower room. And we don’t have a washing machine. I stayed like this for three days.

After three days, some men from security came to help me make some cover around my bed, to have some privacy inside. It was OK. I got some privacy in my bed, and I stayed about one month and twenty days in this camp.

I translate for women, because most of the people in this camp don’t speak English, just Arabic, and if anybody needs to ask for something, for help or to make an objection about anything, I translate. After one month, there were big problems because of the shower and the bathroom. The toilet room for the men was closed, so men and women must use the same toilet, with separate times for men and women. The women don’t accept this situation. We all went together to the office manager and asked, please, we need a toilet only for women all the time, because outside it is so cold, we can’t use the toilet outside. We also have pregnant women, and old women. They can’t go outside in the night and use this toilet.

The woman security guard doesn’t accept my word or anything. She tells us, “You are in Germany, you are equal, you can use the toilet together. I can’t make a toilet only for women and ask the men to use the toilet outside. It is not legal.” She made many rules in this camp. It is so aggressive. We can only charge our phones at certain times.

I ask the office, please, we need a place for women and a place for men. Everything is so bad in this camp. The food also. We have insects in the food, the food is so bad. You can only drink coffee or tea three times in the day. Just three times, when you eat breakfast or lunch or dinner, you can make a cup of coffee or tea afterwards.

One day, a woman needed to make milk for her child, because he is crying, he is hungry. Security doesn’t accept to give this woman hot water to make the milk for this child. She was angry. She found someone in camp who had an electric pot to make hot water, but when the water is ready, the woman makes a mistake—she burns the hand of her baby. She is crying when she goes to the office to tell them, please, help me, because you didn’t accept to give me hot water, I made this mistake…

We had an Egyptian woman as a security woman, in our camp. She works as a security woman in this camp, but if you want some help translating from Arabic to German, she will do it, but she does it incorrectly. She is bad. She doesn’t want to help us in the camp. I don’t know what she tells the office manager about me. She translates for the office manager, because the office manager doesn’t understand the English language very well.

Another person from camp and I wrote in a paper that we had something not so good with a woman security officer in this camp, please help us, so this woman doesn’t return to this camp. And I ask all the people who speak Arabic to write their name and sign this paper. When I finish it, I go to the office manager and show the paper. He doesn’t accept something like this. He tells me that we did something against Germany’s government, against the people of Germany, that everything in the paper is not correct, and that the people in the camp don’t understand why they wrote their names and signed the paper.

After that, he decided to throw me out of the camp because I’ve done this paper against the security woman. The security woman wants do something at the police station, go to the court in Germany. I don’t know, actually, what she can do. Anything is not good for me. I am so scared about this woman. The office manager decided to throw me out of the camp and put me on the streets, at night. I don’t know, it is really bad, but this is really the situation for most of the people in Germany.

“Now I’m pushed back to Croatia, and my ID is in Slovenia.”

Testimony of I., a 30-year-old individual from Afghanistan

This testimony was recorded in Zagreb on 18 February 2016

When we finally reached the Slovenian-Austrian border, they put us in three lines; one for each nationality [Syrian, Iraqi and Afghani]. Facing the translator, I showed him my papers. He asked me where am I from, my date of birth, and why am I going to Austria. I told him I’m going to Austria to seek international protection, as I had to flee home because of the Taliban insurgency and armed conflict. I told him I’m going to Austria to find shelter, as my papers said.

Then the translator told me I’m not from Afghanistan. I’m from Pakistan, he said. I told him I’m not from Pakistan. I’m from Afghanistan, I said. He told me that I speak differently than Afghani people. I told him there are many ways of speaking Pashto in Afghanistan, not only the one he can recognize. Every one and a half kilometers, people speak different Pashto. Some speak hard, some fluidly, some quickly, and so on. I told him that I don’t speak Pashto the way he speaks; I speak Pashto in my own way. I asked him, has he ever visited Afghanistan, Paktia Province, District of Shwak, where I live?

I saw other translators cooperating with other people, but mine didn’t. Maybe they had some kind of deal. Maybe some were taking money from people. They took me aside, put a red ribbon on my hand, and took me to a room with five other people from Iran, Syria and Iraq. This happened on the 24th of January.

In the nighttime, police took us to Postojna detention center. It was six or eight of us; there were another 25 people in the detention center when we arrived. When we left, there were more people, more then fifty people. We were there for 22 days.

A police inspector, helped by a translator, told us that if we can prove we are from Afghanistan we could go to Austria; if not, they will send us back to Croatia, if Croatia accepts us. I told him I could provide him my ID, but I need time to receive it from my family back home. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a way to directly contact my family, but I managed to do it through friends from my village who had been in the camp with me in Austria.

Finally, when my ID was about to be faxed to Postojna detention center, I was sent back to Croatia without the possibility of extension. So now I’m pushed back to Croatia, and my faxed ID is there in Postojna.

When I left Afghanistan I had documents and ID with me. After twenty days, we reached Turkey, and then Bulgaria. We were a group of thirty or forty people. When we passed the border with Bulgaria police stopped us. We were brutally beaten. Bulgarian police snatched all property from us, including our documents.

When Slovenian police took us from Postojna detention center to the Croatian border [Bregana] it was early in the morning. We didn’t have any breakfast, nor water. We were taken to a room with an open toilet, neither beds nor chairs in it. The four of us were held there for ten hours without food or water. We asked for food several times.

That happened two days ago, on the 16th of February. They gave us papers saying we need to leave Croatia within thirty days, and let us go. We were given 100 Kuna for the bus tickets to Zagreb, from a translator at the police station. When we arrived in Zagreb, we found an old abandoned building to spend the night.

We thought there was much more respect for human rights in Europe, before leaving home. But considering what happened to us on the way, we are very, very disappointed.

Featured image: 1 March 2016 at Idomeni. Source: Aid Delivery Mission (Facebook). Please visit them online and donate (or visit them in real life and work).