Transcribed from the 25 June 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Undercommoning is an attempt to understand and celebrate the ways that, underneath the corporate university, people are building forms of solidarity, building alternative modes of study and research, and building connections among students, faculty members, university staff, and people who have been excluded from the university. We’re trying to understand and build links between all the different people who are struggling in the shadow of the university.

Chuck Mertz: It’s time to abolish the university. It’s time we move into something new. It’s time for a revolution within, against, and beyond the university. It’s time for undercommoning.

Here to tell us what that is: Cassie Thornton is a feminist economist and artist who uses dance, writing, visual art, hypnosis, experimental research, tours, and radio to reveal debt as a source of solidarity.

Max Haiven is an assistant professor of political economy and cultural studies at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. He is author of three books, including Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life.

And Brianne Bolin is from Precaricorps, a group that “works to improve the lives and livelihoods of contingent faculty undergoing financial hardship, to educate the public on the way colleges function in the-post recession US economy, to be a source of faculty-related news, and study the role of college faculty in the US economy.”

Bri, let me start with you. How precarious is the life of an adjunct professor nowadays? I don’t think a lot of people know how much the employment structure has changed at colleges over the last twenty or thirty years.

Brianne Bolin: Over the last twenty or thirty years, we’ve seen a decrease in tenured faculty, who have stable jobs and livable incomes—and time to research, and time to study, and time to teach—from 75% of the professoriat in the 1970s to 25% today. And the other 75% of faculty today are made up of contingents; 50% are adjunct. I was paid per course, per semester, generally with no guarantee of a job next term. It was always up in the air.

We are so precarious, in fact, that we often get assignments the week before classes start. We will get classes taken from us if a full-time faculty member’s classes do not fill; they’ll take ours and then we’ll be out of work. Or maybe we’ll be asked to pick up another one for which we’ve done no prep work over the summer.

The last 25% of that pie, the contingent, non-tenure track full-time faculty, make a wage around $35,000 ($40,000 is the upper level) and they have to do a lot of teaching, generally something like four classes per semester plus administrative duties.

So we are extraordinarily precarious. A lot of stress and anxiety goes into that life.

CM: How do you think that affects students and the way they learn at a university? How does that affect their education?

BB: It is affected in many ways. While we are excellent educators (for the most part) in the classroom, because we have so much background and experience, we teach far more classes than a tenure-track member would. We often don’t have offices and don’t hold office hours, so we’re not available on campus for our students even though we might want to be. We’re actually at another campus teaching another class to make money.

This, of course, is not speaking for everybody, but those of us who have to pile on classes to teach don’t have time left over to put towards studying and intellectual pursuits, time that we would have if we were given a solid job. I believe that one of the most detrimental effects of the contingency of the professoriat is that we aren’t producing as much knowledge as we were in the 1970s.

CM: Let’s get to that, Max, this idea of it being better back in the 1970s. Is this all new? All these problems that undercommoning points out are happening within the university, are they new? Can we just go back to some glorious day of universities when it was wonderful ivory towers, and everybody was learning and sharing?

Max Haiven: Yeah, I think if you’re a rich, white man you can. I think if you don’t happen to fit within those categories, you wouldn’t necessarily be quite so successful. I think there’s a lot to be said about comparing our situation today to what we’ve had before—with the proviso that what we had in the 1970s and 1980s, before the neoliberal revolution dismantled the university: those things were there because people struggled for them. The idea that we could have a critical curriculum, that we could have job security and tenure, that we could have academic freedom—those things only existed because people fought for them. And, like so many other things in society over the last twenty or thirty years, we’ve seen the complete dismantling of it.

The position of the undercommoning group that I’m a participant in is that while it’s important to show what we’ve lost, and show those things that our forebears fought for—and that have been taken away from us, like academic freedom and job security)–we also need to move beyond simply nostalgia for the university of the past, because it never quite existed in the way that we imagine it did.

And a lot of other things could exist instead, things that would maybe fulfill what we want a university to do, like educating us, providing a forum for research, providing a space for study, providing a space for community. Maybe that could be provided by a different institutional framework entirely.

CM: So undercommoning is the movement. How would you define undercommoning, Max?

MH: Undercommoning is an attempt to understand and celebrate the ways that underneath the corporate university, underneath the dominant institution which today is so corporatized, people are building forms of solidarity, they’re building alternative modes of study and research, and they’re building connections among students, faculty members, university staff, and people who have been excluded from the university. What we’re trying to do in the undercommoning project is understand and build links between all those different people who, in one way or another, are struggling in what we call the shadow of the university.

CM: There was an Undercommoning Collective article at ROAR Magazine. In it, it said, “Along with the Edu-Factory Collective, we understand the university today as a key institution of an emerging form of global racial capitalism, one that is a laboratory for new forms of oppression and exploitation rather than an innocent institution for the common good.”

Cassie, how much does the university reinforce racism? In what ways do you see it reinforcing racism?

Cassie Thornton: So many ways. One is by creating a value system where everyone believes that the main goal in a person’s life is to go to university, that it’s the highest calling for a person and is such an important form of status-building. In this climate, for-profit universities can come in from the side and charge people whatever they want for an extremely low-grade education, and target people whose families have never attended school, and people who can’t afford other forms of education or aren’t exposed to other types of education. That part is really racist.

CM: Max, when we think of the problems that we see at the university, or the way that undercommoning criticizes the university—is this something that’s just happening at the level of the university, or across all levels of the US education system? Because it seems to me that the K-12 education system is more open to new ideas, and the university is more of an institution that doesn’t change as education changes.

MH: The older model of university education, which Paolo Friere called the “banking model” (where we send the student into the classroom and fill their head with knowledge, and then extract it later at the time of the test, so that the boss can extract it later on the job), has been extremely amenable to the neoliberal revolution. You can transform a university from this pious institution with an ideal of research and knowledge and inquiry into a big gumball machine. Students slot in their money (or, more accurately, their debt) and pull out this high-falutin’ degree, which testifies to acquired skills that now employers don’t have to pay for by training people on the job; second of all spits out a worker who is so heavily in debt that they are desperate to work and are less likely to organize with their fellow workers for better wages and working conditions. The existential claustrophobia of owing so much is such that people’s horizons for what society could be—or should be—narrow to the constant dog-eat-dog struggle merely to keep one’s head above water.

I think that’s what the university produces today. The Edu-Factory Collective, which is in some ways a predecessor to the Undercommoning Collective, had a slogan: “As once the factory, now the university.” Which is to say that under capitalism, at one point the factory was the central institution; it was the institution around which society pivoted, it produced the social relations of the age. They might have overstated the point, but they make an important contribution by saying now the university does that.

If you are excluded from university because you don’t have enough money, or by virtue of race or citizenship status, then your life chances are fundamentally constrained. If you go to university and emerge with debt, what you are being produced as is this human subject, this container of human capital, who is desperate for work. And if you emerge from a really prestigious university because your parents had a lot of money to send you there or because you had great marks in high school, then you are spat out into the equally austere and exploitative hyper-high-class white collar workforce who is administering this whole system.

I think the perspective here is that the university sits on top of this massive system, and it is increasingly geared towards it. And K-12 education is simply geared towards preparing students to somehow enter into those slots. But for more on K-12, I would turn it over to Cassie, who was just doing a project about the Chicago public school system.

Students might think they are the “customers” of the university, but the real customers within the university are the loan companies and the banks. It’s the students’ work to intercept that and to create their own culture among each other. Learning is social.

CT: In the same way that we’ve corporatized universities, primary and secondary school education has become another site of great financial extortion. So as we’ve been critiquing the university and the way that it’s become a financialized institution, the primary and secondary school education systems in the United States are worth far more money, and thus have created an opportunity for the finance sector to make major bank off of kids.

There are different estimates, but public higher education in the United States costs about $65 billion to keep the universities open, and primary and secondary school education in the United States is a $650 billion business. So while we’ve been turning towards the university, the investors have turned towards kids’ education.

I’m really curious to see what plays out in the next few years, because not only is the Chicago public school system really close to bankruptcy, but it’s happening all over the country. We know about Detroit, but there is also Philadelphia, Stockton, Baltimore, Boston, and New Orleans—so many school systems are really screwed. There’s almost no funding coming from states and cities; they can’t do it, and so it’s this amazing moment for investment bankers to come in and redesign schools.

CM: Bri, can this be solved by simply going back to publicly funding universities at the level that we used to fund them? Can this be fixed by Bernie Sanders’ promise of having school universally paid for?

BB: That is one of the solutions, I have to admit. The Strike Debt Collective discovered that it would only take $15 billion to fund higher education for the entire nation. And in his book, Why Public Higher Education Should Be Free, Rob Samuels points out that $15 billion is the same amount that we spend per year to fight the war on drugs, which is a losing war and a misguided war which perpetuates more racist institutions. So that’s one option, if that were able to be compromised upon.

Without that, it becomes up to us to reinvent the institutions, not just revise what’s going on within our own unions and our own schools. I was an adjunct at Columbia College for ten years, and we saw our union go through bargaining over and over—and even when we would win one of our struggles, it wasn’t winning. For instance, a professor who taught a course on Israel and Palestine had his classes pulled from him, and there was a giant campaign to get them back, including teach-ins; we had a petition that went worldwide, and he eventually got his classes reinstated. And the next year they pulled them again.

They just don’t give up. No matter what gains you make, the administrative class, the managerial class in the university will try to pull them back. So organization is really key. One of the projects I’m working on with Precaricorps is something called the Invisible Army. We may be invisible to ourselves, we may be invisible to the administration (definitely as adjuncts, we are invisible), but that gives us a lot of room to play between the lines, and a lot of ways to subvert the traditional university.

There’s no way to “go back,” as was mentioned before. But moving forward, I think we need to organize our own collectives; we need to recognize each other as members of this particular army, and take down this managerial class by hook or by crook.

CM: So in your opinion, are labor conditions still getting worse even to this day? Just continually getting worse?

BB: On the one hand, they are, yes. Frederick Douglass said (I’m paraphrasing of course), your own acceptance determines how poorly they treat you. Eventually, you’re in a position where you have no choice but to take this class that pays $2500 a semester. What choice do you have, really? When it comes down to it, you have a family to feed, so you stay there.

But on the other hand, there is a radical unionization movement going on right now with AFT and SEIU, called Faculty Forward. Adjuncts are organizing all across the country, and seeing really wonderful gains. At Tufts University they have one of the best contracts in the nation; adjuncts are now making $7500 per class, and the national average is just $2800. That’s a significant gain.

We have a long way to go, and as I said before, it’s a continuous fight in the neoliberal university. It’s a matter of moving forward and subverting and unionizing everything, any way we can go about it.

CM: Cassie, you know that people are going to say that if the Undercommoning Collective is asking for the abolition of the university, then it is anti-education. What would you say to people who would argue that you’re anti-education?

CT: Education can happen anywhere. The feeling that you have to come to an ivory tower and be separated from society in order to learn seems incredibly wrong. Schooling doesn’t necessarily equal education. The cost of school to people’s lives—a lifetime of debt and work—just doesn’t seem to balance out in the greater scheme of what I believe learning could be.

CM: Well, what could learning be? When I was reading this article at ROAR Magazine, one of the things that made me feel good about university life was thinking about the times at college that you enjoyed yourself—it wasn’t because of the college itself, it was because of the energy of the other students.

Is part of the problem that, just like workers don’t realize that they are the means to production, students don’t realize how important a role that they have at university?

CT: Sure. I think students might think that they are the “customers” of the university, but the real customers within the university are the loan companies and the banks. It’s really the students’ work to intercept that and to create their own culture among each other. Learning is social. There is an illusion that when you come to university, you’re paying for your own individual education, and you’re going to become your best self. It’s an illusion because nobody is going to become their best self in isolation.

CM: So Max, how do you feel the university falls short, then, in making well-educated, well-informed citizens?

MH: I think that they’re not doing that. What we’ve seen over the last forty or fifty years is a move away from any sort of critical curriculum that could create well-informed citizens, towards professional degrees (and the professionalization even of fields like English or sociology) that are geared towards spitting out compliant workers.

Maybe we should step back a bit and question what a good citizen is. To be frank, I think a good citizen is a revolutionary these days. And I think universities have taken it as their task, increasingly, to eject revolutionary thinkers and to police them. We’ve seen massive increases in security budgets on campus. As Bri mentioned, there is a wholesale attack on freedom of speech and academic freedom going on (with the silencing of critics of Israeli state policy as the prime targets, but only the first of many different targets). We’re seeing that universities are cracking down on students and faculty who speak out in ways that might offend donors or corporate sponsors.

So in many ways, the university is doing a better job than ever in creating a certain type of citizen. But that’s not necessarily the sort of citizen who is going to be able to help see us through the incredible problems that this country faces, or that my country faces in Canada, or that we face as a global population in an age of devastating climate change and rising fascist politics.

What undercommoning is pointing towards is the idea that the capitalist economy as it exists today, with the university as a key part of it, is going to kill us all. Some of us quickly, others of us slowly. And we need to figure out ways of taking care of ourselves and taking care of one another outside the rule of money.

CM: So do you think that the university-as-such, as you call it, actually slows progress, Max?

MH: It speeds up progress if we understand progress as the accumulation of capital for the ruling class. It’s been totally recalibrated to move progress forward in that way. If we think about progress in terms of what sometimes gets talked about as human rights, or in terms of equality or the progress of the human spirit (whatever that may be these days), I think yes, the university-as-such, the university as an institution, the university as a corporate or economic entity, is slowing it down.

But what we’re seeing, as Bri mentioned, is that there is a new wave of incredibly profound organizing happening on campuses—which we refer to, following the work of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, as the undercommons—that is not just protesting the university but reinventing the university from within. I would also point to the incredible work of Black Lives Matter activists in this country who, when they are organizing on campus against the turgid whiteness of the curriculum or against anti-black policing on campus, they’re not only saying that we want the administration to do something different, they’re actually reinventing what the university is and could be, from below.

In Canada, where I’m from, we have incredible indigenous student movements on campuses. They’re doing a similar thing, reinventing what a university curriculum could look like—and not just demanding that one be implemented by the administration, but actually creating it at a grassroots level, providing those educational opportunities and building a different community in the ruins of the university.

CM: Bri, how do we reinvent the university? Because what the university does right now is give you accreditation. It gives you a document, your diploma, that is a certification of your skill. How does working outside of the university still allow people to get the attribution they need—I know this sounds weird—in order for them to get a better job?

What do you do? How do you make a university outside of the university that still allows for this accreditation?

BB: I know of a couple examples right now that are semi-functional, and I can’t really promote any of them wholeheartedly, but there are alternative institutions cropping up, like GCAS, the Global Center for Advanced Studies, and the New Center. A lot of them are housed online. That’s one option.

Another option is to go after the accrediting agencies. ACIS is being attacked right now because of the lack of scrutiny they’ve given these for-profit institutions which are now taking even Map Grant money, all sorts of money—GI Bill money is going to these institutions. The accrediting agency is under attack for letting these things happen. There are many ways.

But to actually have a full-time working job, I don’t know yet. That’s for the collective to go on and take some time to do this! I’m a post-doc right now, and leaving academia, and I have a son to raise, but people who are able to put the energy out, please do! Please create these new sites and these new spaces. We are finding each other, and every day it becomes easier to find each other.

CM: The Undercommoning Collective wrote at ROAR Magazine: “To resist the university-as-such from within is to recognize that it has already turned us into criminals in its own image, that the university today is already a criminal institution, one built on the theft of the time and resources of those it overshadows. We who enjoy its bitter embrace must refuse its codes and values of ownership and propriety.”

Cassie, what criminality does the university teach us to engage in?

CT: I think it teaches us to do what we need to survive as individuals, and not to think of ourselves as a collective. But I think it also provides an opportunity to be criminals against it. One of my favorite writers about student debt and student movements is Annie McClanahan, and she says that when there is so much debt among so many people—when so many people have so much debt that they can never pay it off in this lifetime—this debt actually changes form. It’s no longer debt as we know it. It’s something else—and maybe it’s a site of solidarity.

CM: Max, how can I get in on this undercommoning? Let’s say that there are students right now up here at Northwestern University—or listening at Loyola, Northeastern, wherever they happen to be listening—how can they get involved in undercommoning?

MH: Undercommoning, as it’s configured right now, is a relay, or an echo. It’s an organ that tries to speak about things that are going on, rather than some kind of organization. However, the Undercommoning Collective is working on a number of different upcoming projects. What we would love to see people do is organize on their own campuses into their own sorts of groups and organizations, whether they are large or small—they could be as small as a few people who get together and talk about the problems they are facing; they could be as large as a student movement or a precarious workers’ movement.

In the next few months the Undercommoning group will be releasing a whole series of provocative articles by other undercommoners throughout the anglophone North Atlantic region: some in the UK, some in the United States, some in Canada. The Undercommoning Collective will also likely be issuing a call for a coordinated day of study and action, probably in October, where we hope that all sorts of groups will either form or get together and have an action or a teach-in or some sort of study session or meeting on that day.

Mostly what the Undercommoning group wants to do is hold the door open for something else to emerge within, against, and beyond the university. But it doesn’t have ambitions to be the overarching political organization of that change. Because the collective is of the mind that change is going to look very different depending where you are, on what campus you are, if it’s a private college or a public university, whether it’s a historically poor university or a historically rich university. We understand that there might be different forms of organizing for people of color on campus, for women on campus, for trans people on campus.

What we’re trying to point towards is that all of these struggles, on some level, are struggling within, against and beyond. These are people who are inside the university, or over whom the university casts its shadow. We can’t just refuse the university as a site of struggle, but we are against what we’ve called the university-as-such, the university as it currently exists, and we are all dreaming of the thing to come after the university-as-such. And as I was saying earlier, I think we are already creating it through our forms of solidarity, through the ways that we learn together, through the ways that we study.

CM: So the university-as-such should be abolished. Should all college students who are listening to the show right now drop out?

MH: I think some should certainly drop out. Some students should go and not pay. Some students should go, and get loans, and not pay their loans back. There is no individual solution that’s going to work for this. What undercommoning is pointing towards more broadly is the idea that the capitalist economy as it exists today, with the university as a key part of it, is going to kill us all. Some of us quickly, others of us slowly. And we need to figure out ways of taking care of ourselves and taking care of one another outside of the rule of money.

The university can sometimes help us do that. There are resources within the university, both intellectual and material, that we can steal in order to sustain our survival. But I think we should have a very different attitude towards the university. The conventional approach to the university is one of a romance novel, that if you love the university enough, eventually it’s going to love you back. That’s done. That’s done for good.

This is a gothic tale; this is a monster. It’s time to stop feeding it and stop loving it, and start loving ourselves, both individually and collectively. And that means, more practically, understanding that the knowledge and the value that is produced in university is the fruit of our collaborations and what we bring to it, and then finding ways to validate and celebrate and cultivate that knowledge within the university as it exists, and also on its margins, and also in places that it can’t understand, interpret, or commodify.

CM: I appreciate all of you being here today. This is a fantastic movement you guys are working with.

BB/CT/MH: Thanks so much.

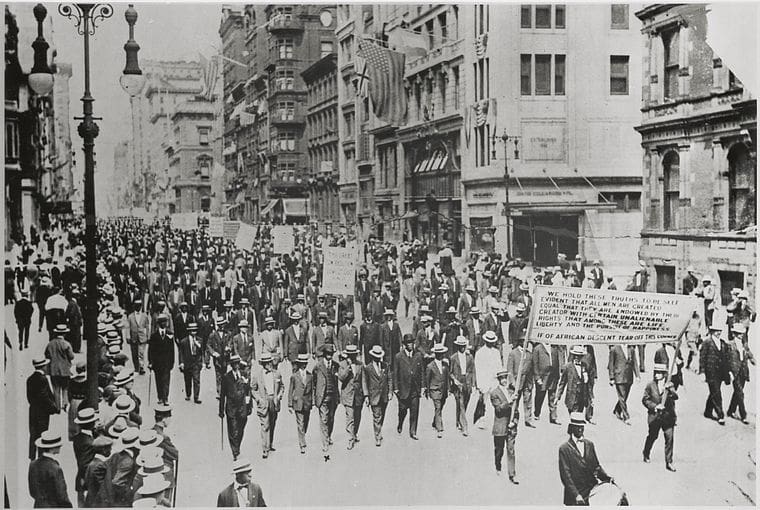

Featured image source: Student Power (Facebook)