Transcribed from the 3 December 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

They lied about what happened at Attica. They said the prisoners killed the hostages. They effectively soured an entire generation on the humanity of prisoners. New York state has a horrific number of incidents of racialized abuse in its prisons now, and this is allowed to happen partly because we got Attica wrong. We allowed the state to tell us what happened.

Chuck Mertz: The deadly violence that took place during the uprising at Attica 45 years ago was covered up until only recently. And it’s been covered back up again. Sadly, the legacy of Attica encompasses all the problems in our criminal justice system that Black Lives Matter is working diligently to expose.

Here to tell us about Attica and what it means for criminal justice today, historian Heather Ann Thompson is author of the National Book Award-nominated Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Heather is an award-winning historian at the University of Michigan and is also the author of Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor and Race in a Modern American City, and the editor of Speaking Out: Activism and Protest in the 1960s and 1970s, which will be published in a new edition next year.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Heather.

Heather Ann Thompson: Great to be here.

CM: Thank you for being on our show.

Not everybody knows about Attica and what happened on September 9th, 1971—when, as your book reminds us, “nearly 1300 prisoners took over the Attica correctional facility in upstate New York to protest years of mistreatment.” Now, not everybody knows what happened, or maybe don’t read it in their history books, because this was continually covered up.

To what degree, at this point in time, do we know what happened at Attica?

HT: I certainly hope, having written this book, that we are getting closer to knowing what happened. The book took about thirteen years to research and write. This event that happened 45 years ago was one of the most extraordinary human rights struggles in US history, and the state of New York worked really hard to narrate it in its own way and make sure we didn’t fully appreciate what actually happened there.

I was able to find sources who the state of New York wished I had not found, in order to tell a story of real dedicated human rights protest. But there had been extraordinary state efforts to make sure that their own culpability in the violence that ended the protest was never revealed—and to make sure that law enforcement was never made to stand trial for what they did.

CM: What kind of mistreatment were the prisoners experiencing up until September 9th, 1971, when the Attica uprising started?

HT: Ironically, the situation in 1971 was much like it is today. In fact, I would argue that today it’s worse. Insufficient medical care, too much time being locked in solitary, insufficient access to family, to food (being fed on 63 cents a day back in 1971): all of these things definitely rankled and made folks stand together and ask for help.

When they asked for help through the system—that is, writing letters and trying to file lawsuits—and that didn’t work, ultimately they became more militant. And a quite unexpected incident brought them together in one area of the prison, in 1971, for a four-day intensive protest and negotiation with the state of New York.

CM: What happened on September 9th? Because these abuses had been going on for a while. Why did the uprising start on that day?

HT: There had been extraordinary tension in the prison, but on that morning, prison management had made a decision to retaliate against a group of prisoners for an incident the night before. They decided to lock this group of prisoners (and the corrections officers in charge of them) in this hallway, with the intention of sending them back to their cells rather than out to rec. But they never told the guards what was happening. They never told the prisoners what was happening. Sheer panic ensued.

In that panicked moment, a gate came open after being pushed on, unexpectedly giving prisoners access to the entire prison. Everyone was panicked, terrified, nobody knew what was happening. But in that moment, calmer heads prevailed and moved everybody into one part of the prison. There, 1300 men stood together, across barriers of race and language and politics, and elected representatives out of each cell block to speak for them. They brought in observers from the outside to oversee negotiations with the state, took hostages so that the state would be forced to negotiate with them, and brought in the media as well, to ‘bring the inside to the outside,’ to show the world what prisons really looked like.

While these negotiations were going on, outside the prison every state trooper barracks from around the state of New York descended on Attica, itching to get inside. Ultimately they started passing out weapons indiscriminately, not recording serial numbers. And on the fifth day, the governor of New York decided to send these incredibly angry men into the prison to retake it by force, even though negotiations were underway. That touched off a massacre. 39 men—hostages and prisoners alike—were murdered. 128 men in total were shot. And then the prisoners were tortured for days, weeks, and months.

CM: What did you discover about the brutality of the crackdown ordered by governor Nelson Rockefeller? And do you think you have enough evidence that if Rockefeller were alive, charges could be brought against him?

HT: It’s doubtful that charges could be brought against the governor, who would have had executive privilege to do pretty much what he wanted. As for members of law enforcement, there is evidence that crimes were committed and that they were protected at the highest levels of government. The governor’s office was complicit in their protection.

But the state police worked very hard to distort the trail, to disappear photographs and distort film and eliminate evidence, so it’s not clear whether prosecutions could now happen. But it is clear that they are very worried about telling the truth about Attica, simply judging by how difficult the records are to access.

They also lied about what happened at Attica. They said the prisoners had killed the hostages. They effectively soured an entire generation on the humanity of folks inside. New York state prisons have a horrific number of incidents of racialized abuse in its prisons, and this is allowed to happen, in large part, because we got Attica wrong. We allowed the state to tell us what happened.

Just like in 1971, prior to the election last month we were in a moment where we were considering prison reform. And now we are once again hearing this phrase “law and order,” we are once again trying to go back to a mythical time of stability. It’s very alarming.

CM: You write how president Nixon supported Rockefeller’s decision to brutally crack down on the Attica uprising. At the time, would this have been a politically popular decision? Especially within Nixon’s “law and order” campaign framework?

HT: It certainly would become popular, but one of the things I try to point out is that going into Attica, the nation was actually quite sympathetic to prison reform, sympathetic to the idea that prisoners were serving sentences but they were still human beings; indeed people were quite hostile to things like the death penalty. There was reform in the air.

Nixon created the anti-prisoner, anti-protest, anti-black sentiment as much as he rode it to power. He created narratives that folks believed, even when they weren’t true, including about why Attica ended so bloodily.

CM: You mention reforms. There were prison reforms that were granted on September 19th (only ten days after the beginning of the uprising and only six days after governor Rockefeller ordered the brutal retaking of Attica by police). But you also write that following the retaking of Attica there was retaliation committed by officers against the prisoners.

So on the day New York City mayor Lindsay helped prisoners get the reforms they had demanded, what was happening at Attica? Were new reforms being adopted even as new abuse was being inflicted on Attica’s prisoners?

HT: The retaliation for this uprising was severe. Recently, in September of this year, again we saw prisoners rise up against really terrible conditions—and now everyone kind of just assumes that it all went back to normal. But behind prison walls, any number of abuses continue to go on, because we don’t get inside and we can’t see it.

The same was true of Attica. We know now because the prisoners continued telling their stories—insisted upon telling their stories, for 45 years—but it is a sober reminder that as citizens we always need to know what is happening behind bars.

CM: The reforms that were put in place on September 19th, 1971—did those reforms replace justice? Did they satisfy the media and the public, or were there calls for a more thorough and open investigation that would hold police responsible?

HT: Had the American citizenry understood that the police are the ones who had killed the hostages and the prisoners, that they are the ones who had shot everybody, that they are the ones who had tortured people—if the citizenry had understood that, there might well have been an outcry. There might have been demand for some justice. And certainly from the people on the inside and their allies—who did know what was going on—there were repeated and continuous calls for justice.

But unfortunately we accept what the media says. When the media says that prisoners castrated and killed hostages, the nation says, “Okay, that must have been what happened.” When the media doesn’t see law enforcement get indicted, they assume there was no evidence.

Attica is a page-by-page reminder of how this actually works behind the scenes. And I have to say, even as a historian and a skeptic, I was often quite taken aback by the level at which this history had gotten deliberately distorted.

CM: To you, what explains the lack of skepticism by the public at the time, when they were being told what amounted to lies by the government about what took place at Attica?

HT: There are two things going on. We have a citizenry that is very skeptical of the government, but we also have a nation that is deeply steeped in white supremacy and in notions about what blackness is, associating it with criminality and associating it with barbarity. So when the media hears a story that black prisoners have castrated and slit the throats of hostages, they don’t seem to need corroboration—and notably neither does much of their white readership. At bottom this is deeply about race. This is deeply about what white America thinks black America is doing or is capable of, and that’s where the reflexive defense of the police also comes into it.

CM: Did prisoners regret the uprising? Did they blame the uprising’s leaders? Was there any kind of retaliation by other prisoners against those who started the uprising?

HT: No, not at all. In fact, what is really remarkable in this story is that the men inside hung together for forty years. They are still out there telling their story, and for over forty years they just kept getting stronger in their determination to correct the historical record—and it’s not just the prisoners but also the hostages, who were also abused and killed by the state. It is really in large part thanks to all of them that I was able to write this book.

There might be plenty of people in government who feel like it’s old news and would be willing to share the records, but the New York state police has stepped in at every opportunity, to say that for privacy concerns they don’t want these records open. Of course they know that the story inside is ugly.

CM: Nonetheless you were able to discover the Who, the What, the Where, the When, and the How of what took place at Attica. How about Why—what is still missing to explain why events played out the way they did during the Attica uprising?

Attica’s legacy is not just repression. It is also about resistance and it’s about the fact that people, no matter how divided or how oppressed, do in fact ultimately stand together on the basic premise that they are human beings.

HT: There’s a lot we still don’t know, but I think what I found suggests the answer. It is confounding: Attica is a tiny town in upstate New York, but from the moment things jumped off at the prison, the memos were flying: to the army, the navy, the air force, the marines, the vice president, the president. We don’t really understand why the US government was so fundamentally freaked out by black protest in America, but when you watch Attica play out, it’s clear they really felt that a lot was at stake.

The ability of participatory democracy to make an impact on our polity had to be resisted at all costs, whether it was the antiwar movement, the native American civil rights movement, or the black freedom struggle. There had to be a line drawn in the sand, and Attica became a huge line in the sand in that moment.

CM: You write, “The Attica uprising prompted the American Correctional Association to conduct a major study of prisons—one which was disseminated widely—which concluded that there was a ‘new type of prisoner’ in America who is living proof that the era of civil rights agitation had gone too far. This new type of prisoner was not only to blame for the ugliness that had happened at Attica, concluded the ACA, but he was a regular presence in and a major threat to a majority of prisons and jails in the nation.

“And lest there be any doubt about why the nation now faced the threat of this more militant convict: it was because these men had spent the 1960s acquiring a knowledge (superficially and otherwise) of history, race problems, street fighting, and the vocabulary of radicalism. And they now believed they were victims of a racist society.

“Most alarming, according to the ACA: ‘this new breed of politically radical young prisoners believe that they are in a holy war against racist oppressors,’ which the organization emphasized did not bode at all well for the law-abiding citizens of this nation.”

How far did this go towards undermining not only a possible prisoner’s rights movement, but also any positive feeling that the US public might have had towards the civil rights movement more generally? Did the lies of Attica derail the civil rights movement in the US?

HT: It certainly soured many mainstream voters who might have been uncertain about “how far civil rights should go.” It’s funny, when I hear you read that, it reminds how much sounds exactly the same today. That could have been written about the Black Lives Matter movement. There’s this idea that when black and brown folks get too angry—too fed up that the system does not deliver basic human rights—then somehow they have gone over the edge; they’re dangerous; they’re now a threat to the very stability of the nation. I think that’s exactly what the politicians at the time felt.

I worry that’s what they think today. The backlash against that can be quite staggering; it certainly was at Attica. And just like in 1971, prior to the election last month we were in a moment of reform—with all kinds of problems and limitations of course, but we were in a moment where we were considering prison reform. And now we are once again hearing this phrase “law and order,” we are once again trying to go back to a mythical time of stability. It’s very alarming.

On the other hand, Attica’s legacy is not just repression. It is also about resistance and it’s about the fact that people, no matter how divided or how oppressed, do in fact ultimately stand together on the basic premise that they are human beings.

CM: How much are the issues the current prison reform movement is concerned about—especially supermax prisons and solitary confinement—how much are those issues related to a backlash against prisoners following Attica?

HT: I think the line is direct. As a historian I never put anything on any one incident, but there is no question in my mind that even though we had already begun the War on Crime before Attica, Attica became an emotional driver. It allows people to feel vengeance when they vote for supermax prisons. It allows them to turn a deaf ear when they hear that even children are being locked up 24 hours a day in these barren institutions.

It isn’t all about Attica. But the lies told at Attica had a devastating impact, making people believe that those behind bars should somehow be punished more.

CM: To what degree, then, is the backlash against civil rights, the backlash against rehabilitation, and the move toward harsher punishment based on a lie?

HT: A shocking degree of the punitive turn came down to the lies told about not just Attica but also about the violence at Kent State, the violence at Wounded Knee, and so on.

One of the most extraordinary things about this period in history is that state violence was at an all-time high. And the people who died and were wounded, whose heads were beaten in, were not the ones carrying guns and wearing badges, not members of law enforcement. But somehow the nation comes away from that period with this idea that antiwar protesters are dangerous, prisoners are dangerous, native Americans are dangerous.

We can’t understand that without understanding the power of distorting narratives, and the power of silencing history.

Things are much worse now. Everyone who has anyone on the inside knows well about it. But the public disconnected from our justice system doesn’t know, and so they are fine with it. This is the importance of shining a light inside of prisons.

CM: What was the reaction to your book from the justice system and law enforcement? Due to your book, are they experiencing new pressure to pursue true justice for the victims of Attica?

HT: It’s interesting. The state of New York has not wanted to talk to me about it, not surprisingly, although it has made noises that it is going to put its records online now (no guarantee, of course, that the interesting documents will be there). But corrections officers and police officers have talked to me privately, written to me—they know that this is all true. And the humanitarians among them are appalled. The corrections officers who worked in these facilities understand that they are less safe because of the conditions. I actually got quite a bit of support from folks who patrol prison tiers or are police on the ground, because they know it’s true.

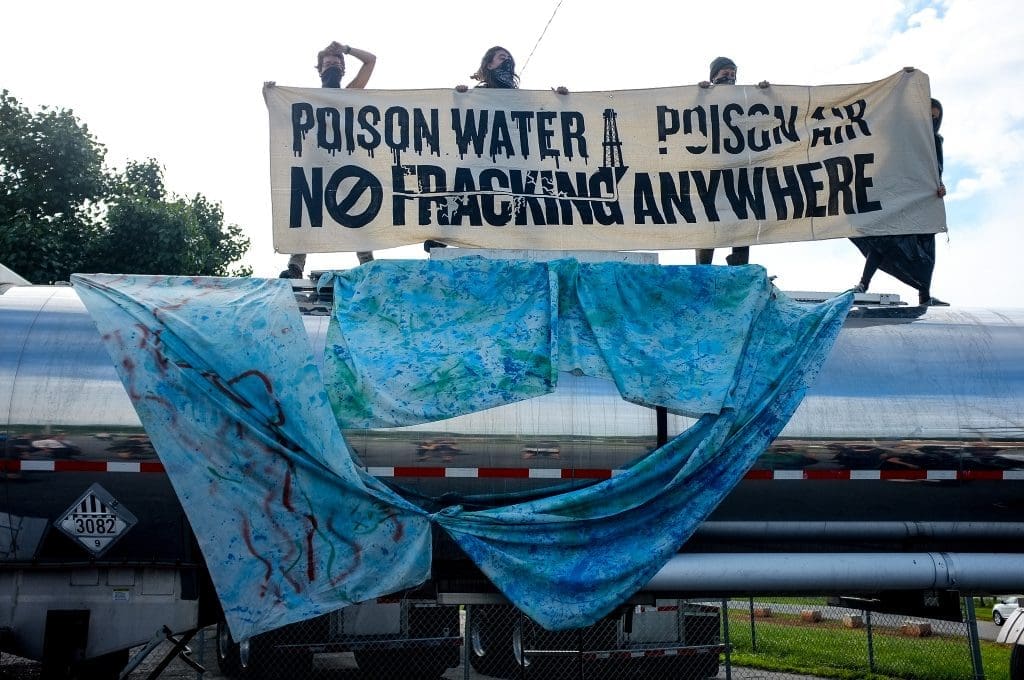

CM: What is taking place right now at Standing Rock—can you see some of Attica in that?

HT: What I see is Wounded Knee. And Wounded Knee and Attica and, again, Kent State—these are all part of a moment in the 1960s where folks stood together in different parts of the country to fight for justice in different ways, but in every one of those instances, the state power that amassed against them was staggering. That’s what we’re seeing at Standing Rock.

Last night on the news, members of law enforcement were saying they were not the ones causing the violence at Standing Rock. And the reporter had just explained how rubber bullets were used, firehoses were used in freezing weather—but somehow the narrative is again being contested. What is making Standing Rock violent? We need to be very clear about what is making it violent.

CM: You write, “Forty years after the uprising of 1971, conditions at Attica were worse than they had ever been.”

Are things worse today in America’s prisons than they were in 1971? And the public is fine with that?

HT: Yes. Things are much worse, and that’s in no small part because subsequent to Attica we’ve also made it incredibly difficult—more difficult than ever—for prisoners to even file legal suit against their conditions of confinement. And the nation is alright with it in large part because we don’t know about it. But I guess I shouldn’t say “we.” Everyone who has anyone on the inside knows well about it. But the public disconnected from our justice system doesn’t know, and so they are fine with it.

This is the importance of shining a light inside prisons.

CM: It just amazes me how it all comes back to a pack of lies told by the government, that the media consumed and then just regurgitated without even checking the truthfulness of any of it. It is shocking to me that we are in the state we are today because the government lied. It’s very depressing.

HT: And we will be again at Standing Rock. If we don’t take care to know the truth of what’s happening there, this will happen again.

CM: And you think that could happen even though people have smartphones and drones and they can film everything? The technology isn’t going to get us over that lie?

HT: Absolutely not. It isn’t the technology, it isn’t the visual we need. It is the interpretation. We’ve seen this with police shootings: you can see someone shot, unprovoked, but if the police narrative behind that shooting is what holds, then we’re in trouble.

CM: So even if “the whole world is watching,” the lies can continue?

HT: Absolutely.

CM: Heather, for all of our guests the last question is always the Question from Hell, the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

There is the famous Fyodor Dostoevsky quote, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” What does the Attica prison uprising and the government’s brutal response say to you about the state of US civilization in 1971? What does it reveal to you about the nature of US civilization 45 years ago, and how much do you think prison has changed since 1971?

HT: What it reveals to us is that the one fundamental injustice in this country that we’ve never fully faced, addressed, and made different is white supremacy, and the absolute disregard for black and brown lives, equality, and justice under the law.

CM: Heather, I really appreciate you being on our show. This was a fantastic conversation, and a depressing but incredible book. Thank you so much.

HT: Thank you so much for having me. Take care.

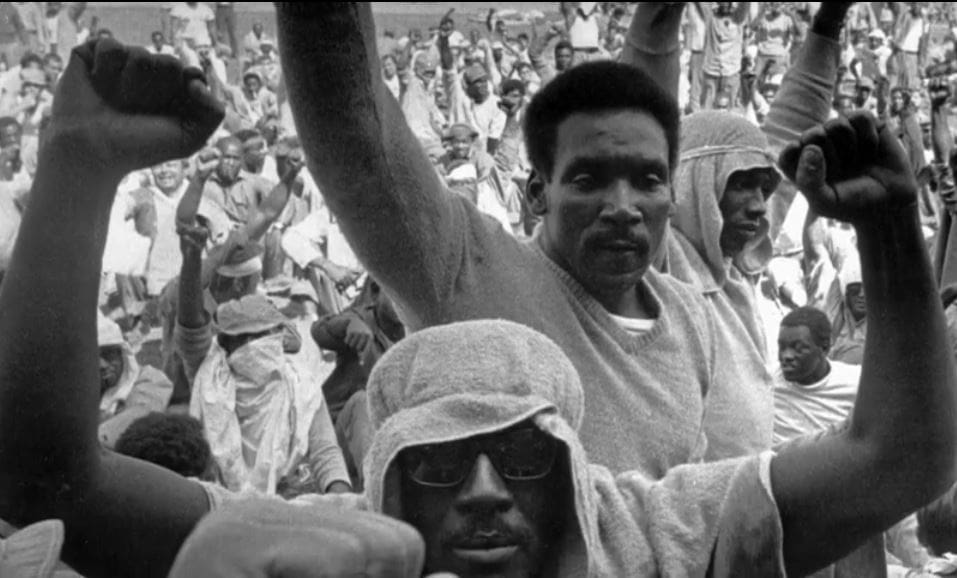

Featured image: still from the YouTube trailer for Blood in the Water