AntiNote: The following short story first appeared in late January 2017 on the website of a refugee-led resistance movement in Germany whose activities the AWC has been following since its headline-grabbing occupation of Berlin’s Oranienplatz and a nearby school in 2012-2014, Refugee Strike Berlin (now more commonly known as the Oplatz movement).

Reproduced with the generous permission of the author, and lightly edited for clarity.

Go Home!

by Turgay Ulu for News of the Berlin Refugee Movement – From Inside

27 January 2017 (original post)

When it was their turn in line, a security guard wearing a walkie-talkie on his shirt pocket told them, “You, you, you, and you are going home now.”

Hüsnü insisted on asking, “But why?”

The security guard explained the rules like this: “There are women inside. There are the guests’ bags and valuables. No way.”

Hüsnü and his friends walked back down the block with a feeling of exclusion.

* * *

When Olcay got the phonecall, he felt excited: a preparation meeting for a demonstration! When the meeting time came, Olcay faced difficulty finding Hüsnü’s house. Since experiencing torture and prison, he always had trouble orienting himself. But Hüsnü came and found him waiting in front of the wrong building. He followed Hüsnü up to the top floor of another apartment block, taking the stairs—there was no elevator.

Some food lay on an untidy table in the kitchen: peppers, potatoes. Hüsnü was preparing to cook. Olcay started to cut vegetables, at Hüsnü’s friendly indication.

Hüsnü was self-confident as always, saying he will cook a delicious meal from his hometown. He moved athletically in the kitchen, putting cooking pots on the stove and talking with the friends he had gathered: Selma, Ferit, and Mehmet were sending photos to each other and laughing together. Hüsnü began commenting along, peeking at the pictures. Then he cajoled them: “All of you have cellphones worth at least a thousand euros but you can’t find any money for other things!” Mehmet laughed and ran his cellphone under hot water to show the others how good it is.

After a long preparation the meal was ready to be eaten, and commented upon. The potatoes did not cook well. Hüsnü joked that it was Ferit’s fault, then changed the subject slightly. He described how his mom would have gone about preparing the same meal. He talked about missing the wine he and his brother used to make in their backyard. His eyes were shining and it was understood how much he yearned for his hometown.

Selma, the youngest of the group, had not been able to stay for the meal. It was not good to be late to the refugee camp where she lived. The strict control system of the camps was restricting all of their lives. They always had to live within the boundaries it set.

Klad was the last person to arrive, and he had brought a Portuguese wine with him. Hüsnü and Olcay were the first to taste it. The others were not sure. A humorous discussion started about the terms halal and haram. They were always restrictions meant only for the poor. The rules about what to do and what not to do: all were decided by traditions, religions and systems. Someone pointed out that they had all decided to go beyond those boundaries a little bit this evening. And besides, there were Christmas and New Year’s preparations going on all over the city. The rest of society was making preparations for the holidays, for entertainment. What they were doing here wasn’t anything close to that.

Hüsnü said, “Let’s do something different tonight, go to a nightclub or something.”

Olcay had lived in Germany as a refugee longer than the others, and he knew the city nightlife better. He had had some experiences, he said. One time, his roommate from a refugee camp in Hanover invited him along to the disco. The security guy at the entrance hadn’t wanted to let his black friend in. He told Olcay, “You can go inside but this black guy can’t.” The two had returned to the refugee camp in a sad and disappointed mood. That night Olcay’s roommate had not been able to sleep, he felt so bad. He was a good dancer! Would he act this way to Europeans who come to Africa? He talked until dawn about how African people treat their guests, how hospitable they are. He couldn’t understand the exclusion in European cities.

In Hanover, Olcay recalled, refugees used to meet at a corner of the main train station. If you want to visit one of the refugee camps in a city, it’s enough to go to that one corner of the main station. We come together at those places to find someone to talk to and share problems, he said, because it is not easy for us to enter into the society. Not being included in public spaces is not just a matter of language. Skin color and social status are determining factors.

Olcay said he had written a poem about this topic, called From the Exterior. He was glad to be among the oppressed class, people like himself. He always liked to observe those environments. He always preferred and continued to live in refugee camps instead of living in a flat, even after he had started the asylum process. This way, he could reorganize strong resistance against inhuman treatment.

He caught himself: he was only trying to explain his experiences because his friends were pretty new at being refugees. He supported Hüsnü in his insistence on doing something different tonight.

That’s how the night began.

* * *

First they went to a cafe, one of those known as “alternative,” but they couldn’t find an empty table—then they saw one near a group of people, but there were no chairs. Hüsnü’s initiative stepped in. He asked a woman from the group with his good German, “Kann ich der Tisch haben?”

The woman told him that he had said the sentence wrong, and corrected him: “You must say, ‘Kann ich den Tisch haben.’” He hadn’t used the correct Artikel, she said.

He replied to the woman, in German, “Okay, I got it! You did surely understand what I mean—thanks for correcting me though!” and took the table with his strong arms and placed it in front of his friends. He found and brought a couple of chairs, too. They started to discuss Artikels in German when they sat down. Someone pointed out how even some Germans cannot use Artikels correctly.

Klad had come to Germany through another European country. He worked in construction and said he sometimes let refugees without work papers work with him. A conversation started about the resistance of migrant workers in Cologne in 1973. It was known as the Ford Factory Resistance, but was declared a “terrorist strike” by the German government and media. At least twelve thousand workers had gone on wildcat strike; most of them were from Turkey. But the German metalworkers union IG Metall mobilized against the Turkish workers—German workers even carried out physical attacks on them together with the police, and as a result, the communist worker from Turkey who had led the strikes had been deported.

Then Klad saw the time and said he had to go home. He said goodbye to everyone and left.

The refugees were once again sitting as a group apart in the alternative cafe. No one ever sat at the same table with locals, that’s just how things generally shook out. People at other tables were chatting and laughing with each other. Hüsnü and his friends got up and played some table soccer, and suddenly it was only refugees playing table soccer. They were always separate, everywhere they went. After a while they got bored and decided to continue with Hüsnü’s plan and move on to the bars in the city center.

Their first attempt to enter a bar was unsuccessful. After leaving the queue, they peed on the street corner. There were no toilets around. Moreover, they did this in protest of their rejection from the bar. Hüsnü said, “We will definitely get into the second bar. I’ll try a different tactic.” Walking down the street, Hüsnü desperately asked women to help them: “We want to go to the club but they won’t let us in. Can you come with us as our friends into the bar? Of course then you can go if you want.”

He was rejected every time. “No!”

There was a big courtyard in front of the main entrance to the second bar, surrounded by a fence. One had to pass through a wrought-iron gate to reach the queue. Hüsnü and his friends did so, and two security guards immediately came and stopped their approach. One of the security guards spoke Chechen, the other spoke Arabic and little German. Both of them had long beards and were wearing special security jackets. One of them translated for the other what Hüsnü said, listened to the reply, and translated back for Hüsnü why they couldn’t go inside. Hüsnü corrected the security guard’s German pronunciation: “Varum or vuğum?” By demonstrating his better German, he was trying to show the security guards that he is a pretty normal person. He asked why he didn’t have permission to enter the bar. “You guys are not German either, you are immigrants too. Why don’t you let us in?”

The securities were foreigners and they wouldn’t let foreigners in. That was a big paradox! If you work at a job and make your boss more money, your color and your language skills are not very important. But these things are a huge problem when you’re trying to go to a club! The discussion between Hüsnü and his friends and the securities lasted a long time. Ultimately the securities said, “We’ll have to call the police if you don’t leave now!” So the second attempt to enter a bar was also not successful. The attitude towards refugees and immigrants had become harder because of the events that happened last year in Cologne and this year in Berlin.

Hüsnü thought they had been rejected twice because of wrong tactics. He thought that perhaps they had been rejected because the others were not speaking good German. He said he would try to enter the next bar alone. Olcay said, “Okay then, if you think so, we’ll wait for you at the corner.”

Hüsnü started to walk confidently through the entrance of another bar. There was a civilian security guard at the entrance. He demanded an ID: “Personalausweis bitte!” Hüsnü reached into his pocket and gave his blue-green refugee ID card to the security, who gave it back, saying, “We don’t let people in with this type of ID.”

Hüsnü was no longer calm. He got really mad, actually: “I speak good German, I’m from Berlin, I was born in Berlin, why don’t you let me in? What’s the difference between me and those people in there?” He was enraged by all the harassment and unfair treatment. So the third attempt to enter a nightclub was unsuccessful too.

* * *

The four friends walked in the street, among people but alone. Olcay had known already that it would end like this, but he hadn’t wanted to hold his friends back. He believed in learning by experience. He had used this method previously to organize the working class. He used to take workers to places of luxury to show them firsthand the huge division between workers and rich people, and talked about the reasons behind this division while letting them observe and feel it.

After the three unsuccessful attempts at going out to a nightclub, they had decided to turn back. Olcay said to his friends, “Look! We are refugees. We tried, and we saw that we don’t have the same rights as others.” Speaking the language well was not enough, he continued as they walked. Racism and inequality have deeper roots. He started telling his friends about his resistance experiences. He told them about the 600-kilometer Freedom Walk to Berlin. They had done this walk because of the prohibitions on free movement, the closure of refugee camps, and the deportation of refugees. They tore up their IDs, the same kind that Hüsnü had shown the security guy, and mailed them to the immigration office. These kinds of protests continued for years. The protesters broke the isolation of the refugee camps, they built tents in the areas they occupied and tried a communal lifestyle. They tried occupations of parliament and of political party buildings, they occupied houses, roofs. They organized successful Europe-wide protests against borders.

Olcay said, “Yes, dear Hüsnü, without resistance we cannot gain our freedoms. Having good language skills is not enough, as you see. All the rights that have been gained in history were the result of long and hard resistance. The dominant classes do not just give you freedom. Rights and freedoms can be achieved only with struggle,” he explained to his friends.

* * *

The four friends got on the metro to go to the alternative cafe they had been at before. Inside the train, the woman sitting next to Hüsnü started to take photos. Hüsnü said to her, “You don’t have the right to take photos without permission.”

The woman said, “Everybody is free, I can do whatever I want.”

“Okay then,” Hüsnü replied, “I will take pictures of you!”

The woman said, “No! You can’t!”

Hüsnü got really angry. Some people have the right to do everything, some people do not. What kind of a system is that? Hüsnü argued with the woman loudly for a long time. The other people in the metro watched the discussion with shocked eyes, and no one supported Hüsnü’s rage against this injustice. Everybody was looking out for themselves. A large majority of society does not say anything against unfair treatment when it is not them being harmed.

After this eventful evening, Mehmet and Ferit understood that it is not possible to integrate into German society just by dressing like them, or with modern hairstyles and smart phones worth a thousand euros. They said, “We are penahende, we are refugees and that’s why we are not accepted. They see us different.” Refugees Welcome: they had heard it many times, but in real life it has no meaning. They learned that by experience.

* * *

People were traveling to visit their parents or relatives, organizing parties, going on vacation over the holidays. But refugees don’t have those chances. Instead they meet each other at home, chatting and cooking traditional foods. That is their way of celebrating Christmas. Actually, Hüsnü and his friends are pretty lucky. There are a lot of refugees living in refugee camps out in the forest, far away from society and social life, and they don’t have the chance to communicate with people. Just being able to communicate with people is a struggle. Hüsnü and his friends are able to visit some cafes, and even that is an achievement of resistance. Some cafes organize solidarity meetings with refugees.

Sometimes Hüsnü and his friends meet in a cafe and drink tea, sometimes they cook traditional foods from different cultures, sometimes they organize film showings and seminars. They are trying to share resistance experiences with new refugees by publishing a newspaper in multiple languages.

The evening after their night on the town, they again met at a friend’s house and cooked food, and watched movies and listened to songs that have been made about the problems of migrants and refugees. But Ferit was not happy today. They learned that he had gotten a letter the day before: a deportation ruling had been made about him. They immediately put their heads together and started to think while they were consoling Ferit. They made an appointment with a lawyer, to challenge the deportation ruling. There had been deportations stopped through resistance and struggle. Klad told them there had even been deportations prevented by occupying the airplane. Ferit was now more hopeful.

Injustice must be resisted. Isolation, outsiderdom, inequality can only be prevented that way. Refugees didn’t come to Europe with pleasure. Continuing war and suffering in their geographies are the dominant forces that drove them here.

As their meetings continued, the content of their conversations got more and more political. The words war, exploitation, and capitalism started to be heard more than before, even in their jokes.

(Translation: Özcan Candemir)

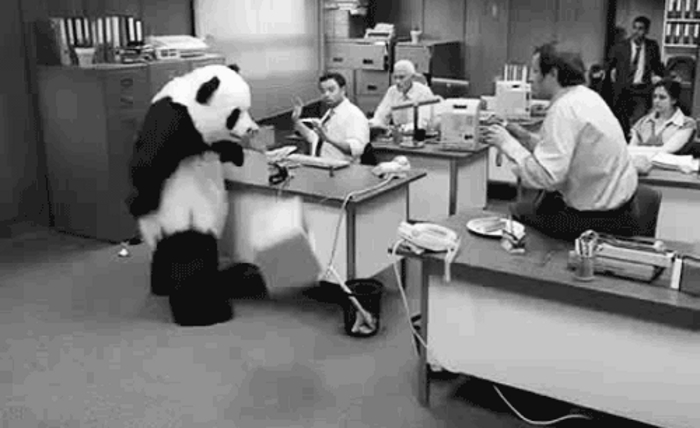

Featured image: Refugee Strike Berlin