Transcribed from the 8 April 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

People who have some advantages have an extraordinary way of flipping the script in terms of understanding their own advantage as entirely of their own making and therefore deserved.

Chuck Mertz: When it comes to economic inequality, there is something worse than income inequality. It’s wealth inequality. And there’s something worse than wealth inequality. It’s racial wealth inequality. You mix up all this inequality and you get a noxious brew that our next guest calls toxic inequality, which is threatening us all.

Here to explain, Thomas Shapiro is author of Toxic Inequality: How America’s Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide, and Threatens Our Future.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Tom.

Thomas Shapiro: Great to be here, thanks a lot.

CM: You write, “The distributional effect of core government policies is actually to create, maintain, and widen inequality.” How do government policies lead to inequality?

TS: The largest driver of wealth inequality in general, and especially the racial wealth gap, is the federal tax system—most particularly in the way we define home ownership as a public good and allow people to write off the interest they pay on their mortgages. It operates in such a way that we invest about $200 billion a year, a huge amount of money, on home ownership, primarily through this mortgage interest deduction.

The lion’s share of that, approximately 86% of that $200 billion, goes to the top ten percent of income tax filers. That’s a way that government policy, over the years (that $200 billion is every single year, it gets repeated), actively redistributes wealth to the top.

CM: You write, “Barriers to prosperity are too high to overcome through individual achievement, and success is rarer than it should be.” But Tom, we’re all told we can pick ourselves up by our bootstraps, and any failure, any shortcoming you may have on the path to prosperity is nobody’s fault but your own. So how rare in success? And how much more difficult is it getting, to succeed?

TS: Part of the reason I titled the book Toxic Inequality was to distinguish where we are right now in the United States: it’s a very different kind of inequality. Inequality has always been with us, and (don’t repeat that I ever said this) inequality is probably always going to be with us. The issue is not so much inequality itself but the threshold, and the damage that it does.

The era that we’re in now is characterized not only by the historic highs of income- and wealth inequality (which is a pretty good start to a bad brew), but by the fact that economic mobility in the last two, maybe two and a half decades has essentially stalled in the United States. The ability of adults to rise above the economic level, the educational level, and the occupational level of the families that they were born into has stalled.

We used to think, as part of our founding cultural myth, that the United States is such an open society that we are the end result of our achievements and our merits (and we’ll sprinkle a little luck in there, of course), and that’s what makes us so much better than the western European democracies in particular. I don’t know to what extent that was really ever true, but these days it’s palpably false.

If we think of economic mobility as a ladder, climbing up to the next rung or two or three or four is what, ideally, most American families would like to do; they’d like to keep climbing that ladder. In this era, the rungs have gotten further apart. It’s harder to get to the next rung on the ladder. Mobility is much harder to attain. That’s part of the toxic inequality brew.

CM: You write how you and your colleagues, in 1998, originally interviewed 187 families across the United States “in hopes of learning how differing wealth resources shape their plans, opportunities, and the futures of individuals from different walks of life. We wanted to understand how people chose schools for their children, decided where to live to best accommodate their families’ needs, and planned to achieve economic mobility. We were also eager to learn about the different pathways that lower-income families and families of color must take as they strive for better lives.”

How aware are those who do not live in lower-income families of the ways other people with lower incomes lead their lives? And how much do you think any lack of awareness possibly, even inadvertently, has led to policies that cause inequality?

TS: Let me answer that in two phases. First, among families that have ample living standards and ample reservoirs of wealth to protect them from the normal mishaps of life that happen to all of us (and from real emergencies), there is not really a great understanding of what it’s like to live at the poverty level. Intellectually, they might have some idea.

But one of the people who we interviewed, for example, in the second set of interviews (we followed up with the same set of families twelves years later), talked about what it’s like at the end of the month for her, when the food stamps have run out, when she’s got no more cash. She talked about how the last week of almost every month, unless it’s a short one like February, she’s making a big casserole that’s got to last three or four days. That’s an ordinary occurrence. People learn to be resilient and navigate and live their lives.

For somebody like myself, who’s got the great privilege of going to Whole Foods almost every day for a meal if I need, that’s not in the normal purview of our daily existence unless we rub shoulders and talk a lot and actively try to better understand the lives of the millions of families in poverty in the United States.

Understanding and empathy, being able to walk in somebody else’s shoes, seeing life through their eyes, feeling it the way they do—that kind of empathy is extraordinary. I would like to see more of it.

The second part, though, has more to do with the cultural lens, ideology and perhaps propaganda. People who have some advantages have an extraordinary way of flipping the script in terms of understanding their own advantage as entirely of their own making and therefore deserved, that all of who they are is because of their individual achievements, their individual character and their great decisionmaking.

That’s the way that a number of the fortunate wealthy families in the book talk about their lives. Let me give you one example. It was from a family in St. Louis that was actually not all that well-off. But here’s the quick story. We’re interviewing them in St. Louis and we’re asking if they like their community. The answer is no, and we ask why, and there’s some racial tension there, and they’re talking about moving to a community down the Mississippi a little further south, more homogeneously white, more people “like themselves,” so the kids will be in a better school system and safer neighborhood (we heard a lot of that).

We ask how they’re going to do that, and they tell us about holding garage sales every weekend. We probed that: what are you trying to sell? “Our old stuff we don’t need anymore.” It becomes clear that after a couple months of holding garage sales, with the same neighbors coming by, they’re not making much money. You’re not going to get a down payment together for a new house with that.

There’s an old debate: is it race or is it class? Is it this or is it that? But when we look at wealth inequality, and the racial wealth gap in particular, the intertwining of race and class is systematic.

Then, having dinner with the woman’s mother several months later, after they’ve started the garage sales, they’re talking about their daughter (who then was five or six) and the conversation turns to how they wanted to move to this “better” community, but they’re having trouble with their garage sales. They’re working really hard. And the woman’s mother says, “Oh, this is ridiculous.” She opens up her purse, takes out a checkbook, and writes a check for thirty thousand dollars.

Now, Chuck, you and I would love to have parents like that. I know all of your listeners would. Parents who not only have the ability to do it, but have the inspiration and are willing to do it. Alright. Good for them.

However, later in the interviews, we asked them to tell us the story of how they bought the house. And when they went through the story, they totally omitted that her mother wrote a check for thirty thousand dollars.

The interviewer went back and said, “I’m remembering from earlier, you talked about how great your mother was in writing that check for thirty thousand dollars. How did that play into the story?” And here’s the answer that just nails the ideology around this: “We worked hard at those garage sales, we deserved it.”

CM: You write, “The interviews underlined how we must understand economic and racial inequality in tandem.” What do we miss in our understanding of issues of economic and racial inequality when we unmoor one from the other?

TS: Unfortunately we want to think in binaries. There’s an old debate: is it race or is it class? Is it this or is it that? But when we look at wealth inequality, and the racial wealth gap in particular, the intertwining of race and class is systematic. To fully understand the racial wealth gap and wealth inequality in general in the United States, we’ve got to understand how wealth was created. We have to understand how it grows institutionally in different areas. Home ownership is a perfect example.

I was both very heartened and simultaneously disappointed by Occupy Wall Street. I was really heartened that finally extreme inequality, wealth inequality has broken through, and there was some public conversation about it. But I was disappointed that race was sidelined almost entirely in that conversation. It took Black Lives Matter and the Dreamers and Color of Change and other grassroots organizations of color and activists of color to bring the racial justice issue back into it.

It’s really critical for any visionary opposition to bring those two movements closer together. For them to succeed, they must understand that racial justice and wealth gaps—and racial wealth gaps—are really about the same set of dynamics.

CM: How do we understand inequality differently when the focus is on income inequality instead of wealth inequality?

TS: Generally when inequality comes up, the fill-in-the-blank frame that people automatically go to is around income. We’ve been trained to do that. Poverty data is about income. Piketty and Saez data is mostly about income. A smidgen of wealth, but mostly about income. Our cultural and justice frames are around income.

When income becomes the main, if not exclusive, part of the formula around inequality, we focus on paid work, we focus on preparation for work, we focus on workplace standards and organizing at work so people actually get paid closer to the value of the product they are producing; we look at that whole set of really important issues for American workers and for all of us. When we look at wealth, the lens shifts a bit. The labor market stays in there, but the window opens up to the historical legacy of the wealth created in previous generations, from which many parts of the population were excluded.

Income can’t be passed along. Wealth is passed along. So we get to talk about inheritance. We get to talk about historical and legacy government policies like land-grant colleges, like the federal tax code, like the institutional dynamics within real estate markets that are mapped on residential segregation and why it is that a home in a relatively homogeneous white community creates more home equity than the exact same home in a more diverse community, nevermind a community that is less than fifty percent white.

You cannot disentangle race and class in that example, by my estimation.

CM: You also write about how through your interviews you heard similar values and aspirations across income and wealth levels. But we’re always hearing politicians and pundits, including president Obama, promoting the idea of “valuing education,” implying education is not being prioritized necessarily as a universal value in the US. On education, did you find the same values from rich to poor?

TS: Let me take it back to the first set of interviews, the set we did in 1998 and 1999. To get into the study, all the families needed to have children about to be in kindergarten or in kindergarten. Then, when we were talking to families about their five-year-olds, it was universally inspirational. As an interviewer, as a researcher, as a sociologist, it was utterly inspirational to hear families talk about the aspirations they had for their young children: their college aspirations, their professional aspirations, what they wanted their lives to look like.

And it wasn’t only abstract aspirations, but they were putting in concrete sacrifices for their children—trying to live in an area that had a better school system, maybe spending a little bit more money for a preparatory program, doing all kinds of things for their kids.

Twelve years later, the aspirational story doesn’t change a whole lot. But in the facts of the matter there is a clear divergence. Middle class and upper-middle class kids—both black and white, but a little more on the white side—are college-bound. The working class kids, almost uniformly, both black and white (and the small number of Hispanic families that we had as well) are not going to college. They are having trouble getting out of high school. A number of them are in jobs already, jobs that unfortunately look like dead-end jobs in the service sector. We start to see how advantage and disadvantage is passed along through families in those moments where their financial resources are the driving factors.

The end of apartheid, Mandela, the African National Congress, the incredible struggle for so many years, the incredible victories—inspirational for a lot of us, myself included—was nonetheless a political revolution and not an economic transformation.

CM: Throughout the book you talk about how wealth inequality seems to be at the heart of the racial inequality that we’re experiencing here in the US. You write, “African-Americans’ historical disadvantage has become baked into the American economy.”

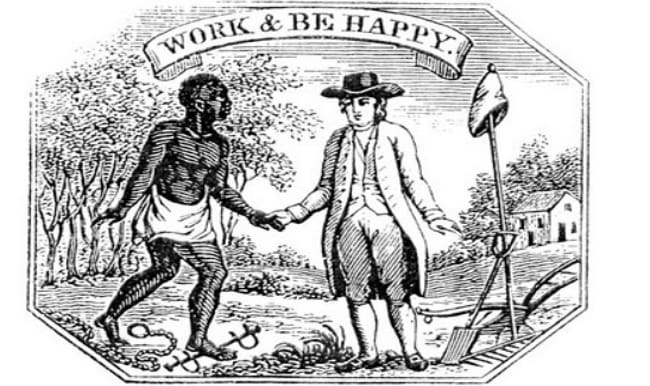

How much of that historical disadvantage can be traced all the way back to slavery? Is today’s wealth disparity an artifact of centuries of slavery and post-slavery discriminatory policies towards non-whites? Is wealth disparity the best argument for reparations?

TS: The racial wealth gap is an accumulation of generations of policy that go all the way back to enslavement. But it doesn’t end with the end of slavery. It gets accumulated even more during Jim Crow, and the data that we present in the book—that the racial wealth gap widens for the same set of families between 1984 and 2013—shows us that even in so-called “post-racial” America, and even though we had some really hard-fought and successful pieces of civil rights legislation around lending, home ownership, higher education, and a lot of other things, and even as good as that legislation was, it did not stop or detour the harm that is being done at an institutional level in widening the racial wealth gap. So it’s beyond just slavery. But slavery was, obviously, a pivotal historical juncture in the United States, and its history continues to spin forward right into the current day.

Let me throw one other historical point in here to help us understand. We’re not just talking about something in our very, very distant past. I mentioned the tax code. But let’s look at social security, too. This national welfare policy to ensure that people, after they could or would no longer work, could live out their lives in some kind of dignity and honor, passed in 1934-1935. Universal for everybody? No. There were occupations that were intentionally excluded in that law: domestic work, agricultural work, railroad work—the occupations that Hispanics and African-Americans were largely concentrated in then. So an entire system is built, and works pretty well, especially in the way it reduces poverty among the elderly—but it excluded huge swathes of the population.

As those and other excluded occupations, through reform efforts in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, became covered under social security, the years you had worked prior to the reform legislation didn’t count. So an agricultural worker who retired after 35 years of work doesn’t get the same social security at the end of that lifetime of work as somebody who had worked in the auto plants. And it’s much more likely that the agricultural worker was a person of color.

Did you want to get to the reparations question? It’s a complicated and great conversation. The work that I do around the racial wealth gap should be at the heart of a positive case for why reparations are necessary in the United States. That could be a period, full stop. But there’s a next paragraph.

I’m very wary of saying, okay, let’s go for reparations as a solution in the United States, without first fixing the deeply racialized composition of public policies and structures and institutions today in the United States. I don’t think you can just deal with the past—that’s what reparations tend to do—without simultaneously uprooting, as best we can, the deeply racialized way that wealth is created today.

It would be great. Don’t misunderstand me. But if we leave the deeply entrenched systems and structures of implicit and explicit discrimination in place, over a period of time we’re going to recreate a gap. It won’t be as bad. But the politics around that will be pretty ugly.

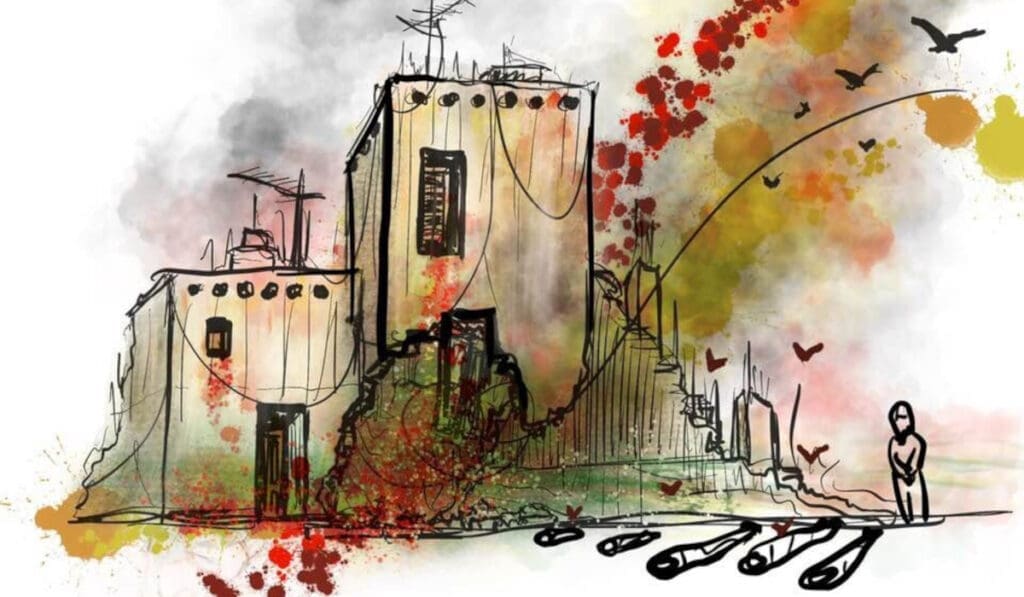

CM: How soon are we looking at a US that has a minority white population which owns a majority—even a vast majority—of the wealth? Are we looking at a US that would resemble apartheid South Africa?

TS: Did you read my bio? Did it tell you I spent six months in South Africa? That’s part of why I went there, to try and think and work with those kinds of issues.

I’ve got a fear about that. But let me get to that in a minute. The demographers tell us that some time in the year 2042, like January 3 at eleven o’clock, the white population will no longer be a numerical majority in the US. For me, demographics are not destiny. The issue is that our institutions, thus far, have proven incapable of preparing for that or dealing with it. All we have to do is look at our schools, which are already a minority-majority system. There is no one group that is a numerical majority in public schools. And we’ve been doing a horrible job with public education for a long time, but especially in the last twenty to thirty years.

We really need to think about what our society and our institutions are going to look like in the future, and how to become more culturally sensitive and culturally competent around the real people who are walking through those institutions and are there for a very good reason.

The second part of that is that part of the alt-right, part of Bannon’s crew, understands the changing demographics. A large part of the immigrant fear-mongering and the executive orders and the policy around that is to move that 2042 year back as far as they possibly can. Because immigrants are the largest part of that demographic change. The second-largest part is birth and death rates in the Hispanic population.

It may not be as intentional as I think, but the alt-right Bannon project around immigration fear-mongering is to keep the United States as white as possible for as long as possible. We see that also with mass incarceration. We also see it with taking away folks’ voting rights. All of that is of a piece, to keep the white electorate—if I can use that as an aggregate term—in political power.

For me, the South Africa equation is a scary one. It’s become more public, I think, in the last five years in South Africa that the end of apartheid, Mandela, the African National Congress, the incredible struggle for so many years, the incredible victories—inspirational for a lot of us, myself included—was nonetheless a political revolution and not an economic transformation. The economy is still controlled by a tiny minority that still tends to be white (although there are “black diamonds”: wealthy black Africans who have become part of the economic elite). But the distance between that economic elite and the rest of the society has really not narrowed since the end of apartheid.

CM: How much is toxic inequality a breeding ground for hate, and even for far-rightwing fascism?

TS: It’s a very fertile breeding ground. Pandering to racial anxiety and immigrant fears has been with us for a long time. The reason I’m conceptualizing around toxic inequality with these historic highs of income- and wealth inequality, the stalled mobility, and the stagnating living standards, is that pandering to racial anxiety and immigrant fears finds a much more fertile soil under those conditions.

We saw an expression of that clearly in the last election cycle, and continue to see it. It operates as a big distraction from the root causes of income and wealth inequality and racial injustice. It moves the conversation away from the upstream causes, and blames it all or a large part of it on some othered immigrant taking your job, or some othered person of color using all of these so-called state welfare benefits so there’s nothing left for the rest of the society.

That’s really the end result of this bad convergence around toxic inequality. The danger and the threat to the United States is the racialization of politics.

CM: Tom, a real pleasure having you on the show.

TS: I’m absolutely honored. Thanks a lot.