Transcribed from the 18 March 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

I’m sure we can all find a half-hour in our day to lose ourselves in our environment and just observe. Look at the world, look at other people, remember that we’re not solipsistically living for ourselves.

Chuck Mertz: The best way to discover a city, to experience the urban landscape, and to understand what its citizens are really like, is to walk the city’s streets and explore, idly wandering, strolling as you take it all in. But not everybody is supposed to be taking to the streets.

Here to explain the joys of walking and the challenges women have faced in doing so, Lauren Elkin is the author of Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London.

How do you define flâneuse, so our audience will know what it means?

Lauren Elkin: Well, it’s sort of a word that doesn’t exist. It’s the female conjugation of the French masculine noun flâneur, which generally means a man about town who likes to wander the streets at will, at his leisure, taking in the urban spectacle and then maybe going home to his garret and writing it up in his magnum opus.

There are feminists, art historians, and literary critics who want very badly for there to be a female version, because women have always lived in cities and walked in cities; what has their experience been? The sad truth is that we haven’t had the same sort of freedom to wander the streets of the city that the flâneur has had.

CM: I told someone about the idea of the flâneur and their reply was that it must be someone who is, in their words, “a bum who does not work.” Is the act of flânerie doing nothing? Is it not working?

LE: That’s a really funny way of describing the flâneur, because he’s traditionally been seen as a super-bourgeois upper-middle class aristocratic man who has the leisure and the privilege to take the afternoon off from work. So actually it is a very classed idea. The idea that a bum could be a flâneur is pretty provocative.

CM: You write about strolling the streets of Paris: “The French word flâneur, or ‘one who wanders aimlessly,’ was born in the first half of thethere is a solace in that. One foot in front of the other, looking at people going about their business. I think it can really put your life into perspective. nineteenth century in the glass and steel-covered passages of Paris, when Georges-Eugène Haussmann [the urban designer who redesigned Paris during Napoleon III] started slicing his bright boulevards through the dark, uneven crusts of houses like knives through a city of cindered chèvre. In the mid-eighteenth century urban design renovation of Paris, the flâneur wandered there, too, taking in the urban spectacle.”

Reading that, I thought of Chicago’s grid system of urban planning. How much do you think the way you are guided through the city by its streets—whether it’s a series of diagonals, a wheel and its radiating lines from parks, as opposed to a grid—affects the way you experience your wandering?

LE: I write about New York in the book—it’s where I grew up—and how I find it sort of difficult to wander on a grid, because you can’t lose track of where you are. The streets are always numbered; you know if you’re going up or down or left or right. If you know the city well, the grid is something that you have imprinted on your mind. In Paris, I frequently operate as if the city were a grid, and I think if I make four rights, I’m going to end up where I started, but that’s not actually the case. If you’re used to one system and suddenly plunk yourself down in another one and behave as if you’re on the first one, then you can get yourself into some really interesting scrapes.

CM: Do you think there is something different about experiencing the city by walking around from, say, walking in the woods or walking in nature or along a beach for miles?

LE: There is. As wonderful as it can be to walk in nature for a long time, there’s something about walking in the built environment, an ethical engagement with it, that commands you to think about the ways the world has been put together and how you might fit into it. There are so many ways becoming aware of the way the city is put together can help you realize the things you want to change about the city itself, or change about the world.

As a woman, for example, walking around Paris, I am frequently reminded that the city is built for the height of a man—an average-sized man and not an average-sized woman. In bus shelters, the seat is too high for me. Toilet seats are too high for me. I’m not that petite. I’m average height for a female. But I continually feel like a little kid in the city, and that’s because it’s not designed for me.

CM: And you write about the experience of writing down and reporting what’s happening: it’s about what you call the intraordinary, “what happens when nothing is happening.” More than anything, does that describe the experience of wandering, of strolling a city, witnessing what happens when supposedly nothing is happening? And what is happening when nothing is happening?

LE: That’s a concept that I get from Georges Perec in his essay collection Species of Spaces, where he says that the daily papers talk about everything but the daily, and that we have to think about the way that the world is put together. He says to “question your teaspoons.” What is under your wallpaper? Why do things work the way they work?

If you’re going on foot or taking public transportation to or from work, and you’re caught up in going from point A to point B. When you stop focusing on the extraordinary or focusing on your destination, and start thinking about what you’ve encountered on the way to work, or why you walk the way you walk, or why this subway works the way it works, or why the map looks the way it looks—that’s when you start to appreciate the intraordinary, the opposite of the extraordinary. It’s the texture of everyday life, and that’s where (for Perec, at least) things can perhaps begin to be different.

CM: You write, “The streets of Paris had a way of making me stop in my tracks, my heart suspended. They seemed saturated with presence, even if there was no one there but me. These were places where something could happen or had happened or both, a feeling I could never have had at home in New York, where life is infected with the future tense.”

What’s lost, in your opinion, then, when a city modernizes? What does the new take from a city?

LE: I’m not super preoccupied with holding on to the city’s past per se. Look at a city like London, where they’ve had no choice—after the bombings of the Second World War they had to rebuild. They lost a lot of that beautiful Georgian or Victorian architecture, and they’ve had to replace it with brutalist cement buildings that have their own kind of beauty or interest. But I am interested in a place being aware of its past and not erasing the fact that other things have happened there. I am, for example, a proponent of plaques on buildings, and stopping to look at them, and thinking about what it might mean to commemorate something, and what we commemorate and who we commemorate.

What I wrote about looking for ghosts on the boulevard is about appreciating that there’s aesthetic pleasure in walking through a city and feeling like you’re not the first person to be there, that there’s this rich history of life, of presence that’s preceded you and that surrounds you. I think it’s because I love to read so much, and I’m a literary scholar interested not only in Virginia Woolf but in reading a whole history of reception of Virginia Woolf and in adding my voice to that discussion. So it’s about companionship.

CM: But you’re by yourself—how is it about companionship?

LE: It’s a way of staving off loneliness in the city. Even if you are by yourself, you’re never really by yourself. There have been people there before you, there are people behind those doors and windows, even if you’re not going to have an interaction with them. I derive a great sense of reassurance from spotting someone in the building across the street, seeing that they’re home, going about their lives, hanging up the laundry or doing whatever it is they do when they are at home.

It takes a certain kind of person, maybe, to find companionship even in solitude, but I think that’s what the city offers us.

The flâneuse is not just the female version of the flâneur; a female experience of the city is its own thing entirely.

CM: You write, “Every turn I made was a reminder that the day was mine, and I didn’t have to be anywhere I didn’t want to be. I had an astonishing immunity to responsibility, because I had no ambitions at all beyond doing only that which I found interesting.”

Did you have this feeling even when you did have responsibilities? Does strolling, wandering, allow you to forget, or at least re-prioritize the tasks that you were supposed to be addressing (or that you could be addressing if you were at home sitting at your desk or staring at your smartphone)?

LE: I think it’s a real choice you have to make. The bit that you read out, that was something I experienced when I was a student at university, living in Paris for the first time. That feeling has definitely not persisted throughout my life.

But I do get asked this question a lot about the way the smartphone affects your wandering. Do I wander less now that I have this phone that gives me GPS and is constantly sending me emails and whatsapps? The answer is the same for both questions: it’s really a choice we can make to keep the phone in our bags and to take some time off from being held to that economy of responsibility and productivity. You can make the decision to turn it all off and go offline for a little while, even if it’s just half an hour. I’m sure we can all find a half-hour in our day to lose ourselves in our environment and just observe. Look at the world, look at other people, remember that we’re not solipsistically living for ourselves.

CM: How much is the experience of wandering the streets open to women? In my experience, that’s been the best way to learn about and understand a city. Is the experience of wandering and strolling not only one of male privilege, but white privilege?

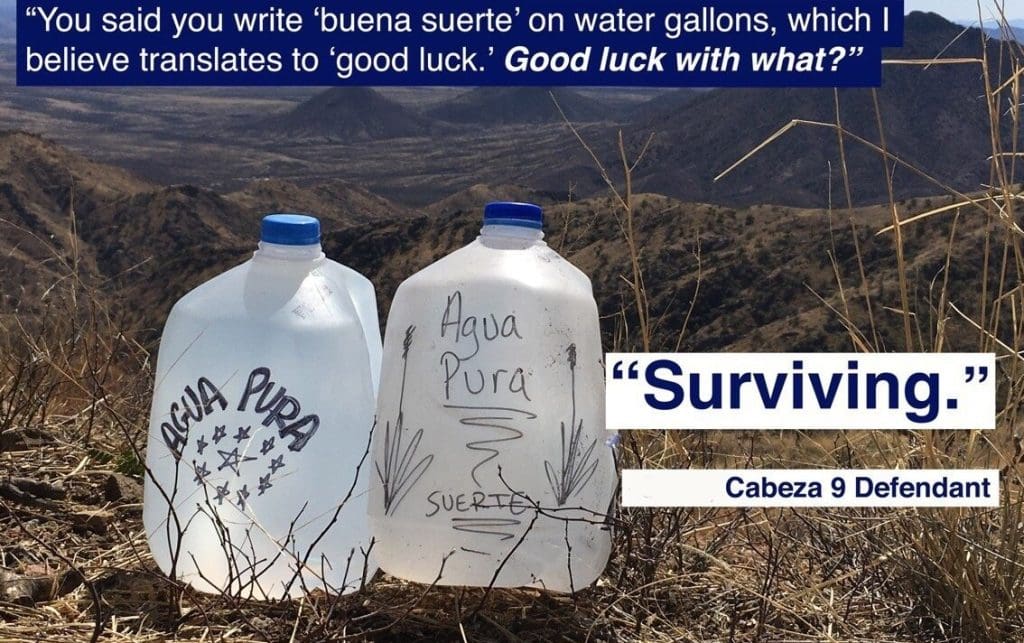

LE: One hundred percent. There are things I don’t have to worry about as a white woman walking in public that someone who doesn’t have that privileged position is going to encounter. I have a good friend who wrote a brilliant essay called “Walking While Black.” His name is Garnette Cadogan. He writes about how if he’s walking down the street, if it’s deserted or dark, if he sees a white woman walking towards him, he’ll cross the street and walk on the other side to reassure her that he’s no threat.

If you look at the writings of black or Mexican woman in the streets, there is a sense of sticking out in a way that’s uncomfortable. It’s not a neutral experience. I think that’s true for women across the board. You do have to look at specific experiences. Audre Lorde writes about this; Jessie Fauset writes about this. Race does play a role.

CM: You write about how you actually did find a definition for the word flâneuse. And you write how this definition “is, believe it or not, a kind of lounge chair. Is that some kind of joke? The only kind of curious idling a woman does is lying down? So in France, when men want to be idle they leave the home and wander the city, but when women do, they still must stay indoors, and instead of exercising, they do nothing?”

What does that reveal to you about the way in which the French historically viewed women?

LE: I think that’s a question that answers itself. If we look at the history of critics trying to reclaim the role of the flâneuse, they say to look at the rise of the department store. This is a place where women can go and roam freely and shop and have a cup of tea with their friends. They can be free to wander in the department store. Or they go to the cinema. These are interior spaces that are offered to us as examples of what women do in public.

Those were important ways in which women were exercising their right to go out and spend an afternoon on their own, but I think it’s more important to look at the street: what was happening between their home and the department store. I had to look at the work of female writers and artists, because I didn’t have access to any archives where one might find everyday women writing about their lives. That’s definitely research I hope someone is doing or will do. But I was really thrown back on the work of Marie Bashkirtseff, who was this wonderful Russian painter living in Paris in the mid- to late nineteenth century who was writing in her journal about how much she wanted to be able to wander the streets of Paris at will, and that because she couldn’t do that she would never be a great artist.

Yeah, she could go to a department store, but because she couldn’t wander the streets and look at whatever nooks and crannies caught her interest, she wouldn’t be able to create the kind of art that would really set her apart from the rest.

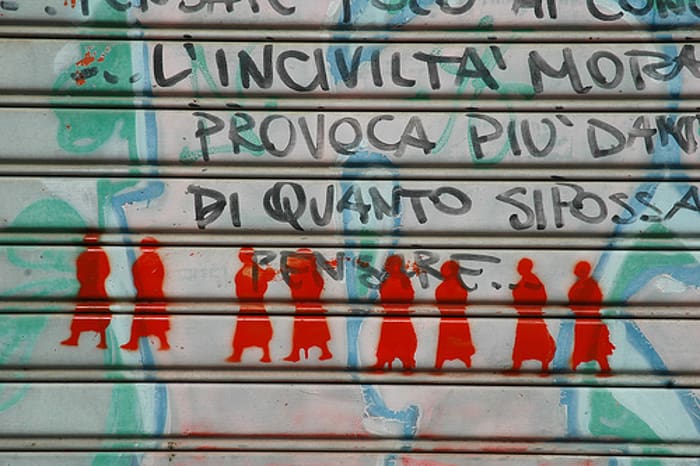

CM: But that’s not to say that women, even when they were more free to be strolling the streets of the city, that they had the same freedom that men had. Even when women were free to be in public, how much was and is that freedom limited?

LE: That’s a big reason for my argument that the flâneuse is not just the female version of the flâneur, but that a female experience of the city is its own thing, that it’s built out of this sense that when we go out in public—even now, in 2017, out in the streets in Brooklyn where I was staying a couple weeks ago—there’s this sense that we either have to be looked after and protected (people asked me, “Are you alright? Do you need anything?” if I was out by myself after dark) or that we might be threatened in some way. Anyone you see might be a threat or might be someone who is going to protect you—or they might be someone who is going to hit on you or catcall you or something. I get the sense that being in public as a woman on the street, even now, is not a neutral thing.

I am very sad about that. I wish that I could move through the city neutrally. And certainly there are times that I can, and I can’t take that for granted. So that’s what the book is about.

CM: You also write about how George Sand would experience the city incognito. How important do you think it is for women to be incognito in order for them not to experience sexism and the male gaze?

LE: It is so sad. I don’t think the onus should be on us to make ourselves incognito or carry around pepper spray or put our keys between our fingers when we’re walking home alone at night. We shouldn’t have to take these measures to protect ourselves. But for whatever reason, I’m not sure why, street harassment and violence against women continue to be a thing. Until that stops, we’re going to have to continue to try not to call attention to ourselves on the streets.

That kind of neutrality that Sand was able to achieve—she did it by dressing like a boy. We can’t go around in drag all the time. It’s nice to wear heels and a skirt. I’d like to exercise my right to wear heels and a skirt on the streets of Paris without getting catcalled.

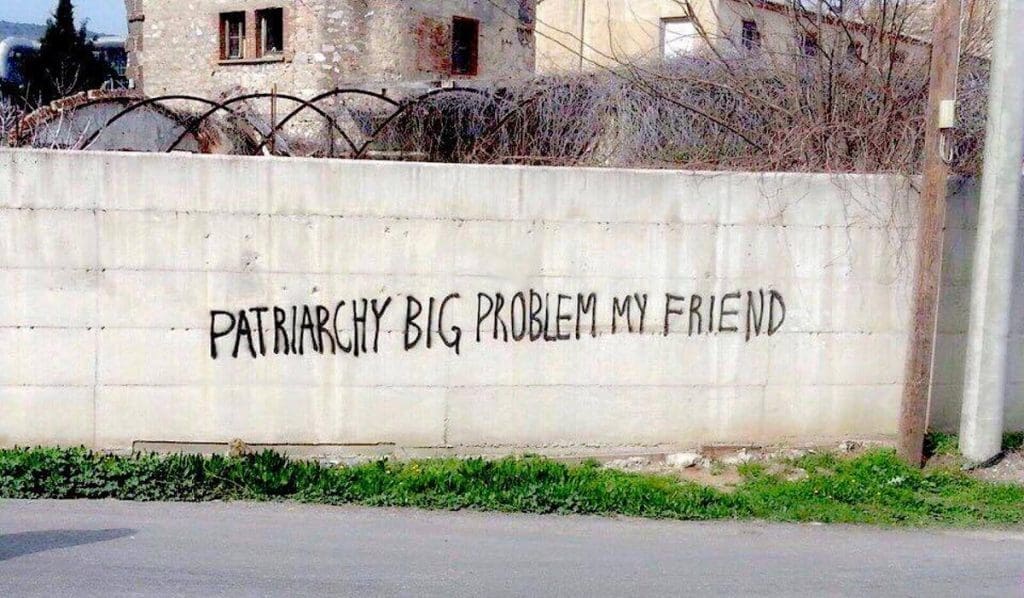

It’s taken for granted that the story of the city and engaging with the city is told by men, and that hasn’t really been challenged until very recently. Flâneuse is an attempt to excavate a female genealogy of public space that can be pitted against the masculine view of the city that doesn’t tell the whole story.

CM: How much does the lack of women as flâneurs—or rather flâneuse—reveal to you the desire of men to be the only ones who understand the world and experience it? Is this about men wanting to be the exclusive interlocutor, the only ones to be involved in the dialogue or the conversation of the urban landscape?

LE: I’m not sure it’s a volition. I cite Will Self or Iain Sinclair, or anyone who is writing about the city, who builds this masculine genealogy of writer-walkers, from Thomas J. Quincy to William Wordsworth to Walter Benjamin, Baudelaire, Louis Aragon, the surrealists, the Situationists—I think it’s just taken for granted that the story of the city and engaging with the city is told by men, and that hasn’t really been challenged until very recently.

Look at the writings of Janet Wolf, who was one of the first people to write about the flâneuse (she wrote an article called “The Invisible Flâneuse”). She argued that our ways for understanding modernity itself and the city itself have been provided by men. We haven’t heard female voices articulating their experience of the city. A book like Flâneuse is really an attempt to excavate a female genealogy of public space that can be pitted against that masculine view of the city. Not to say that it’s wrong, but to specifically cite it as a masculinist construction and a specific construction that doesn’t tell the whole story.

CM: You write, “Will Self uses Psychogeography to title a collection of his essays. However, Self has declared, not without some personal disappointment, psychogeography to be a man’s work. Confirming the walker in the city as a figure of masculine privilege, Self has gone so far as to declare psychogeographers a fraternity.”

Then you write, “The great writers of the city, the great psychogeographers, the ones you read about in The Observer on weekends, they are all men, and at any given moment you’ll also find them writing about each other’s work, creating a reified cannon of masculine writer-walkers, as if a penis were a requisite walking appendage, like a cane.”

How much do you believe the city is misunderstood because of writer-walkers being predominantly men?

LE: We’re only getting half the story. There are far more ways of engaging with the city and other narratives of the city that come from female writer-walkers or female artist-walkers or just female walkers. I think Will Self is being pretty provocative there. That’s his modus operandi in general, to say something daft and see what people say back. But he’s probably just pointing out what I was saying before, that there’s this echo chamber of writing about the city that’s all done by men, so of course he’s going to think psychogeography is a man’s business. You really can read men writing about walking in the newspapers every weekend.

But a book like Flâneuse stages a necessary intervention to say, look, there are women out there walking and writing about the city, and we just need to make them more visible, include their work in The Observer on the weekends; talk about them in conversations on the radio. We’re out there. We just need a little bit more attention.

CM: How much of a feeling of home do you get when you explore outside your home? I find it an odd contradiction: you have a house or an apartment, which people define as a home—but did you get more of a sense of that being your home when you spent more time outside of your home to understand the city?

LE: That’s a really good question. When I was in Tokyo, for instance, as I write about in one of the chapters, I left my house very infrequently, and when I did leave my house I felt really alienated and had a very hard time coming to grips with Tokyo because it wasn’t a city I could walk in very easily. It took a lot of repeated attempts to discover different neighborhoods before I could learn to walk there. That made me feel both alienated from the city and from my home, to be spending so much time there.

Woolf writes in her essay “Street Haunting” about the ways we are a certain self at home when we’re surrounded by the things that we’ve picked out, the things that make us who we are, and when we step out in the street, as she writes, we become part of this “republican horde of anonymous trampers,” where we’re equal to everyone else on the street and our identities kind of fade away.

In that sense, the streets can become your home in a way, but as a really depersonalized, collective, communal home. And it’s through the act of walking that we claim that space and can become at home within that space. That is an interesting paradox, but it’s a productive one.

CM: You write, “Sometimes I walk because I have things on my mind, and walking helps me sort them out.”

For you, is it a kind of meditation? Or is meditation not the right thing to compare it to, because you’re not trying to clear your mind—instead, you are opening it to the world around you?

LE: It depends on the context, but sometimes if you are sitting in your house and you’re dealing with this problem and you just need to get away from it, what’s the first thing that you do? I’m going to go for a walk. Go outside, get a change of air. So it’s not meditation in the sense of clearing your mind, but it is clearing your mind of the thing that was plaguing you, and replacing those thoughts with looking at how inconsequential everything in the world is. We’re all out there having our heavy-duty thoughts and our serious lives and our crises and everything, but we’re also all out there going to the supermarket, putting a letter in the mailbox, doing the things that we do every day (to come back to the idea of the intraordinary).

And there is a solace in that. One foot in front of the other, looking at people going about their business. I think it can really put your life into perspective.

CM: I’m about to use a word I do not like, because I think it has been abused and misused in some disturbing and disgusting ways. I’ve even heard it used in a way that can actually disenfranchise, deny and reject—what it is intended not to do. And that word is empowering.

How much do you think wandering the city helps overcome fear and any potentially exaggerated feeling you may have of a city being a dangerous place, especially for women? How much do you believe walking, strolling, experiencing the city, recording what you see, expressing it, allows you to be stronger, more confident, especially in controlling your own life?

And is that what men have against women who are walking and strolling and wandering the streets?

LE: There is a kind of guy who is threatened by a woman walking around the city strutting her stuff and obviously looking confident about herself. Maybe there’s something in those guys that makes them want to take her down a peg. That’s happened to me on a few occasions, that some guy just gets in your face and wants to fuck with you.

Unfortunately, there are men who probably do feel that way. But I am also eager, as a big fan of the male half of the race, to say #NotAllMen.

CM: Thank you, Lauren, I really appreciate you being on the show.

LE: Thank you for having me.

Featured image source: Shamsia Hassani (Instagram)