“There are whole worlds between talk and action.”

Interview with Marco from the Giambellino-Lorenteggio Housing Committee (Milan)

by the malaboca collective for Lower Class Magazine

27 April 2017 (original post in German)

Note from Lower Class Magazine: The neighborhood of Giambellino, on the western periphery of Milan, is a classic workers’ quarter from the fascist era. But anyone who visits the neglected neighborhood will notice something other than just the somewhat run-down buildings: many of the apartments are squatted, and there are many other squatted spaces harboring self-organized infrastructure. More than a few of the neighborhood’s residents are organized within the local initiative Comitato Abitanti Giambellino Lorenteggio; they squat, build out, and manage these spaces.

A large proportion of the people living in Giambellino and organized in the local committee migrated to Italy in hopes of a better life and a steady income. Still, the outlook in Italy is pretty grim. The welfare state has been hollowed out, and high unemployment, exorbitant rents, and racism often determine much of a migrant’s everyday life. Along with Milanese comrades who have turned the corner on classically insular autonomous political traditions in order to organize with their neighbors, these residents manage their lives together in solidarity.

Over the past year, the malaboca collective conducted interviews with people from the committee and asked them about their concept of revolutionary local politics and what self-organization has meant for the neighborhood. For the occasion of the conference “Do it Yourself: Grassroots Organizing, Counterpower, and Autonomy,” (April 28 to 30, 2017 in Berlin), we present here an interview with Marco from the Giambellino-Lorenteggio Housing Committee. Marco has been with the committee from the beginning. He was one of the comrades who had been living in the Pizzeria squat, only a stone’s throw from Giambellino. When they were evicted, they began squatting buildings in Giambellino and resumed their organizing there. Marco has had an important role within the committee, because his South American background gives him a certain caché with the large South American community in the neighborhood.

malaboca: When we attended the assembly of the neighborhood committee a couple days ago, it was important to you that we also participate and not just observe. Why?

Marco: On the one hand, I wanted you to stick around and meet people. On the other—and this was the more important thing—I wanted you to see the difference between this assembly and the assemblies that we know from our earlier political experiences. The classic mode of political praxis has always had a certain view of things; there are already pre-formed ideas, positions, or ideologies. It’s different here. Here, we do politics around concrete needs. I wanted you to see how diverse the modes of political praxis could be among people who are not used to organizing themselves or going to meetings. Because that’s the difference: it’s slow, but it works. And I believe it’s the only way that people will become directly active themselves.

We all have certain experiences and certain skills, for example because we have studied or because we have engaged in struggles, and now those are things that we can place at the disposal of other people. On the other hand we get to learn of the treasures—like culture and that sort of thing—that other people have learned in the course of their lives. This is how a reciprocal learning process emerges. It’s not just us teaching someone something, or them teaching us, but rather we learn together. This is something new. It’s something new for us, and it’s something new here in Italy. We are hoping to change conditions this way. Because we are in a phase right now where we are paying for our lack of strategy over recent years. This has caused a political catastrophe in Italy, which we are all experiencing now.

malaboca: What role does the neighborhood committee play in the area where you work?

Marco: Most of the people who made up the committee in the beginning needed a place to live. They couldn’t pay the rent—or didn’t want to, because then they wouldn’t have any more money to buy themselves a bottle of water or to send to their families. There are many migrants living here—I am one myself—and most of them came to Italy so they could send money to their families.

Many of the people in the committee came to Italy in order to make a better life for themselves—but this is often only a dream which is quickly shattered. If you can find work, you get humiliated and poorly paid. But in most cases you can’t find a job at all, and you quickly find yourself in a hopeless situation. Migrants in proletarian neighborhoods are the lowest, the last, the most marginalized in this system. But at the same time it is these people who are the most ready to do a lot, because they have nothing to lose.

In Ecuador, where I come from, it was different: there you have your family, your friends; your life is there. There, perhaps, you have a place, a foothold, a basis from which you can look for work or from which you can strike out on other paths. Here, if you don’t know anybody, it’s completely different. It’s different in a Western country where interpersonal relationships barely exist.

Of course there are different communities here, for example not just a South American community but also a large Ethiopian community. The connections within these communities are good; someone calls up another, and word gets around really fast that there’s a committee you can go to if you need help. That’s how these communities have grown within the committee. The first people were from Ecuador; because of them, mostly people from Ecuador came, then the first from Peru and so on. That’s new in the neighborhood.

Our work also has an effect on people outside of the committee. Even if they don’t organize with us directly every day, they often join us, for example, when the police comes to evict an apartment. They can identify with what we do and think it’s right. The committee is not the neighborhood, and the neighborhood is not the committee. The neighborhood consists of so many different things. We are an important part of it, but still just a part.

malaboca: And what has changed, exactly, through your praxis?

Marco: I think above all we’ve changed ourselves. One example: in the Peruvian community there is the practice of Polladai—it’s like a potluck fundraiser. The concept is to create a solidary dynamic, to sell home-cooked food and use the money to support a collective project or someone who is having difficulties.

In the beginning we argued a lot about if it is okay to sell meat and so on. What we didn’t understand was the materiality of the whole thing. It’s not a primary concern whether people eat meat or not, but that there is a process of organization beyond our basic conceptions that we needed to learn. This is something that is already baked into the practices of communities that came to Italy through migration.

One day when we needed to raise money for our activities and we were considering throwing a party, inviting this or that band and selling drinks, the people said: “No—Pollada!” And then they organized this event, and we made way more money than we ever did with parties that took more than a month to organize and just stressed every one out, even if they can also be fun. This way it was much more organic, something that already existed. When we arrived in Giambellino, there were already these forms of collective life beyond our ideas that we had to learn about.

You could say we are interested in a politics of life. This would mean that people can identify with that which they create together, and will, if necessary, also defend it. This is the point of departure for all further transformation.

Another thing that has changed is that self-organization now stands at the center of our work. When we started to work on the issue of housing, it was clear that we could not make the same mistakes as other political structures that have already been doing this work for years, nor did we want to repeat the things in their work that we never cared for in the first place. In Rome, for example, the housing justice movement is quite large—several thousand people are involved and it’s been around for over twenty years. But there it seems like a lot gets driven and decided by the most experienced comrades, and we didn’t want this dynamic. It’s important that you bring yourself in based on your own capacities, but there also has to be a balance, such that everybody has something to do in order for things to function. When I put it that way, it sounds like a pretty easy task, but it isn’t. This is something that has to be constantly talked about and improved over time—especially when things aren’t going well. Over time, many tasks have come up: for example, that we need a treasurer who manages the money of the committee and decides how we invest it. At the same time we need an electrician, a carpenter, and someone who can make breakfast on days when we need to be ready for the police because they’ve threatened eviction.

That is more constructive than when someone tells people, top-down, what they should do. Of course you can put pressure on them by saying, “If you don’t do this, you’re not part of the committee.” Then perhaps people come even more ready. But there is really no direct activation of a base—in other words, of people with whom you are struggling together—in this manner. The goal is to have an organization in which every person, every family, every member of the committee has a place. From the beginning we have tried to work towards this goal, but ultimately this happens now from the base of the committee outward, from the people who always show up and who you know you can count on one hundred percent.

malaboca: But what exactly motivates people in the neighborhood to join up and become part of the committee?

Marco: We try to motivate people towards active participation based upon their own concrete needs, and, by standing together in solidarity, to create opportunities to stand up to oppressive political discourses in an appropriate and just way. Because that’s what’s missing. The problem is that we believed, in recent years, that it’s enough to simply say something is just or unjust in order to unite people around a cause. We forgot that real material and social conditions prevent people from having the courage to decide to organize themselves and fight. People don’t organize themselves not because they’re cowards or they’re too bourgeois. They don’t organize themselves because they’re not used to it. Therefore the crux of our political work is the transition from unsatisfied needs to political action.

And it works to say: “We are helping ourselves together—today for you, tomorrow someone else, and we’ll do it together. You squat a house because otherwise you won’t have a roof over your head, and because there is no such thing as just politics.” It’s not that comrades will find a house for you—we’ll go and get them together. And we defend them together.

Little by little it is starting to work. People start to come to the assemblies, and then they start to go to demonstrations. People gradually start to notice what is happening. They get active in the first place, perhaps, because they are pursuing a personal goal, like getting an apartment. But our work does not stop there—otherwise we would be operating on the same level of charity work as a church or other aid organization. All that does is clear one’s conscience.

Starting from the territory on which we live, we want to interpret life in our neighborhood anew. Therefore our discourse is not just about living space, but about living, about the whole life here. There is already a social life here, to which we as activists never really had access before because we always arrived with these big questions and ideologies. But when you live in a neighborhood and try to get to know people in order to grow with them, you have to ask yourself whether you are part of a territory, or in a territory in which problems are born and solutions found.

To be part of a territory, to be an entity, is something that we have been missing in recent years. We always criticize the significance of identity among activists.ii But I think it is important to identify with the place where you live. There is a big difference between identifying with a political group and identifying with a neighborhood committee. When you are part of a neighborhood in which social relationships exist that are important to you and that you can’t find anywhere else in the city, then you will defend it. No one is ready to defend something with which they do not identify. There are few collective contexts that fulfill this function in a good way—a solidarity organization in your neighborhood is one of them. You could say we are interested in a politics of life. This would mean that people can identify with that which they create together, and will, if necessary, also defend it. This is the point of departure for all further transformation.

As different as struggles might seem, we have to try and connect them, in order to create a block that acts as one, politically. Because ultimately capitalism is our opponent. This includes those who are in power and those who hold the monopoly on violence. The more committees there are, the more collectives, the more workers’ organizations, the better.

malaboca: You’ve sketched out the conditions of your new praxis, but where do you want to go with it?

Marco: At the start, we hemmed and hawed a lot and didn’t really know what we should do in order to come in contact with the people we ultimately wanted to squat with. There is so much vacancy in Milan; within all this empty space we can create something new. Shortly after we squatted the first building here, the city initiated a huge media campaign threatening two hundred immediate evictions. That intimidated us. We thought, now that we have finally started and the whole thing is up and running, this happens and we’re not in a position to fight it. But it was the totally normal people themselves who took to the streets, attacked the police, and defended themselves against eviction. It was this resistance that led to the plan for these two hundred forced evictions to be stopped. Thus was born a kind of spontaneous coming-together in the neighborhood, among people who up to that point weren’t really organized.

After that we said the primary goal has to be that more committees in other neighborhoods get founded, and that a shared organization among the neighborhoods should be created that could one day lead to the collective organization of all the proletarian neighborhoods. Such an organization would be in a position to take joint political steps in the city in order to escape the status of isolated minority committees and become a federation that builds autonomy and the political means to improve life for everyone.

Parallel to that is the second goal: to connect the struggles of the committee to those that already exist, for example with the workers in the shipping and logistics sector. A large proportion of these workers are migrants and members of the union Si Cobas,iii which is much more confrontational than the traditional unions and also is organized in a much more grassroots democratic way. The workers who fight in this manner always put themselves at enormous economic risk. Perhaps they have to take care of their families, pay their rent and so on—many give up a strike at a certain point because the danger of being left with no money is just too great. If there were an organization that could say, “Hey, don’t worry, we’ll help with your rent problem,” that gives you strength and security. To build such a practical combination of forces, a practical unity—not a collection of different groups and organizations, but really a unity that is realized in everyday struggle—would be an incredibly great thing.

Another example would be student organizations. We don’t want to isolate ourselves in the periphery and say, “OK, the police doesn’t come into our neighborhood anymore; we’re staying here,” while in the rest of the city it looks very different. How should we come in contact with the young people out there?

As different as all these struggles might seem, we have to try and connect them, in order to create a block that acts as one, politically. Because ultimately capitalism is our opponent. This includes those who are in power and those who hold the monopoly on violence. We don’t have such a block because the only thing that’s going on here are the Centri Socialiiv where political groups sit around and have lost all contact with reality and the world around them. Therefore: the more committees there are, the more collectives there are, the more workers’ organizations there are, the better.

malaboca: What advice or message do you have for people who really want to do something, to help them along the way?

Marco: Don’t hold on too tight to your ideas. That’s something that we have learned here. Certainly everything I’ve told you about will continue to be modified over time, and better ideas will keep coming out of the neighborhood. Our work, as it stands now, is not the same as it was at the beginning, and we are trying not to set too firm goals for ourselves. We are trying rather to follow guidelines, with the readiness to leave them behind and strike out on new paths in order to arrive sometime, it doesn’t have to be tomorrow. If we don’t have the ability to see transformations, to be patient, to listen, and to work together in the critical moments, then we are damned to lose.

The majority of people has accepted the feeling of defeat: “Why should we fight? Just to get smacked with another ticket? Why fight, if we won’t achieve anything anyway?” That’s precisely what we have to change. Above all else we must give the impression—no, not the impression, the certainty—that it is worth it to fight. Because when you fight, there will be success; when you fight, you can get lucky. It won’t just be fines and jail time, but a life you haven’t yet tasted. This feeling of certainty, this drive to defy the world—this is something that everyone should experience.

Translated by Antidote

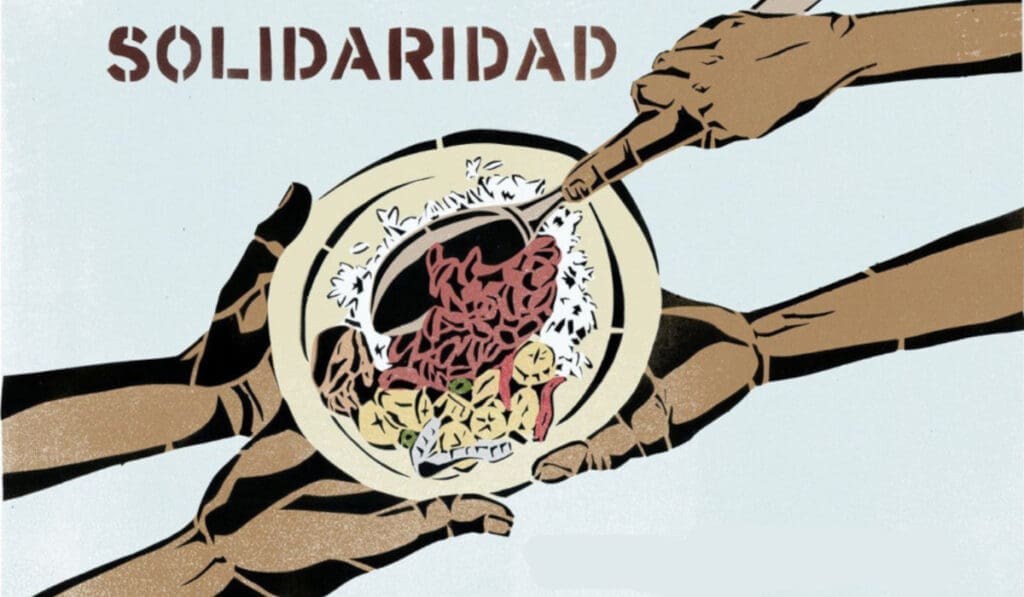

Featured image source: Squat!net. All other images: Comitato Abitanti Giambellino Lorenteggio (Facebook)

***

i Latin American-style grilled chicken, derived from the Spanish word pollo.

ii Above all subcultural, isolating identities in relation to a political “scene”

iii Italian labor union whose praxis and experience of workers’ councils and self-management in the metalworking sector goes back to the 1980s

iv The Centri Sociali (social centers) are the classic autonomous centers of Italy, which tend to act almost exclusively within their insular scenes