Transcribed from the 3 September 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

There’s a notable silence around how antifa was a very relevant force against the dangerous neo-Nazi subcultures that arose in the eighties and nineties—perhaps fairly, because they were subcultures. Of course these are histories that aren’t going to make it onto CNN and MSNBC, let alone Fox News. But they’re not unrecorded in antifa history.

Chuck Mertz: The fight against fascism has been going on for a very long time here in the US. Time and time again, Nazis have risen up, and time and time again antifascists have pushed them back down. Here to help us all better understand antifa, its strategies, tactics, context, and history: writer and political analyst Natasha Lennard posted the article “Don’t Give Fascism an Inch: to defeat white supremacy, we must confront it directly,” as part of a debate package written for In These Times‘ September issue.

Natasha writes about politics and power for publications such as Esquire, the Nation, the Intercept, and the New York Times. Her most recent writing at the Nation includes “Not Rights but Justice: it’s time to make Nazis afraid again.” Natasha’s book Violence with Brad Evans will be released later this year.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Natasha.

Natasha Lennard: Hi, thanks for having me.

CM: Natasha, last weekend in San Francisco, International Longshore and Warehouse Union local 10 shut down attempts by a far-rightwing group—that had recently been involved in violence with counterprotesters in Portland, Oregon—to have a rally in San Francisco. As Peter Cole wrote in In These Times this week, “The ILWU boycotted ships loading material for fascist and racist regimes in Japan in the 1930s, Chile in the 1970s, South Africa in the 1980s. It stood as one of the few organizations to condemn the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War Two. It actively fought racism in its own workplaces, cities, and nation. The ILWU shut down all west coast ports on May Day of 2008 to protest US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. On Trump’s inauguration day, ninety percent of rank-and-file members in local 10 refused to report for work.”

So Natasha, how new or how different is today’s antifa from, say, what’s been going on for decades when it comes to action taken by groups like the ILWU in their fight against fascism? How new is this?

NL: As a formation, an ideology, and a tactic, it’s nothing new at all, not considering the self-organized street gangs fighting against Mussolini’s fascists, or against Oswald Mosley’s fascists in 1930s England. So we’re not even just talking about the past few decades.

It’s new in the current discourse about emboldened fascism and ways to counter it. But certainly antifa, antifascism, is not some new collective or some conspiratorial group trying to hand victories to the right with elaborate displays of violence. It’s an old and well-established set of tactics that antifascists have used to directly confront fascist upsurges, in the awareness that often conservative, liberal, and government institutions are ill-equipped to face these forces and indeed are often quite happy—especially with the configuration we’re seeing now in the white house—to enable them.

So this is nothing new, and it’s particularly odd and baffling for those of us who do know this history—the labor-organizing history, the anarchist history, and even the punk scene history in the eighties and nineties, not all that long ago—to see the major newspapers all around the country talking about antifa as if it were aliens who landed from outer space for the first time. What’s new, I think, is the surprise of these liberal media organizations. That’s what I find unusual, not the existence of antifa.

Although there is a grand history of cautious liberal-centrist and centrist-conservative media standing against and acting shocked by direct action tactics. I don’t know why we see this pattern except as it was explained by Martin Luther King: it’s people who are interested in the defense of order rather than justice. So in the same way the presence of antifa is not a new iteration, the presence of centrist-liberal fear-mongering is arising again. It’s a familiar pattern.

CM: What does it say to you, then, about the state of liberalism or the Democratic Party when they prioritize order over justice?

NL: It says to me that they’re sticking by their cautious moderate laurels—which have never actually been on the side of justice, historically. They consider themselves, post hoc, to have been the sort of people who would have supported the sort of direct action that Martin Luther King would have advocated for, but only when it’s comfortably in the past. The sorts of responses coming from opinion writers from every major newspaper, Nancy Pelosi, and, tragically enough, Noam Chomsky, is the same condemnation of direct action that was all too common in the civil rights movement.

There was a fantastic op-ed by four clergy members in the New York Times, thankfully a counterpoint to some of the awful reactionary fear-mongering garbage about antifa’s direct action, pointing out that these sorts of opinions from the center and from liberals are exactly the sorts of things that look shameful when we see them iterated during the civil rights movement.

CM: You write, “A more recent history of antifa in both Europe and the United States illustrates the success these tactics can have, particularly when it comes to expunging violent racist forces from our neighborhoods and defending vulnerable communities while also creating networks of support that do not rely on structurally racist law enforcement for protection against racists.”

How often do antifascists have successes for which they are not given their due?

NL: I would say consistently. When victories do occur, the same cautious moderates are all too happy to take credit. Recently there have been some voices giving due credit to antifa, for example Cornel West thanking antifa for their defense and their presence in Charlottesville. But no, there’s a notable silence around how antifa was a very relevant force against the very dangerous neo-Nazi subcultures that arose in the eighties and nineties—perhaps fairly, because they were subcultures. But these were really notable successes and showed how antifascist local organizing and awareness exposed local communities of neo-Nazi skinheads, closed down their punk shows, closed down their organizing spaces, and made it impossible for these countercultural, subcultural neofascists to gain ground.

Media—dependent as it is on the spectacle—over-exaggerates the role that the street fight plays in antifa organizing. It is a relevant and historic part of it, but it’s not what the vast majority of time and energy is dedicated to, which is research and exposure of fascist organizing and individuals.

Of course these are histories that aren’t going to make it onto CNN and MSNBC, let alone Fox News. But they’re not unrecorded in antifa history. For example, Mark Bray’s recent book points out that there are a number of clear examples of antifa successes that speak against this paranoiac screed of “They’re just handing victories to the right by punching Nazis.” That’s simply unempirical.

CM: Also, you write, “When neo-Nazi Richard Spencer and his National Policy Institute held their annual conference in DC last November, antifascist activists exposed the event, its attendees, and where its members were dining, in an attempt to not only protest but to disrupt and shut down the conference as well as Spencer’s dinner plans, succeeding at least in dousing the white nationalist in a foul-smelling liquid. News and monitoring sites like NYC Antifa, Antifascist News, and It’s Going Down have been reporting on the NPI and exposing their members and their conferences since before Trump’s candidacy.”

So how much can we credit antifa activists for getting the media to recognize the far-right leanings of many who support the Trump administration? How much of the goal of antifa is an informational and awareness goal?

NL: A huge amount. Obviously, media—dependent as it is on the spectacle—over-exaggerates the role that the street fight plays in antifa organizing. It is a relevant and historic part of it that I wouldn’t say is not representative, but it’s not what the vast majority of time and energy is dedicated to, which is, as you say, exposure: finding out who these people are, who they are organizing with, which symbolism and dog whistles and veiled signals they’re using on Twitter, which avatars they are using, exposing the language and the discourse by which these people are organizing, and exposing the individuals.

It actually aligns, as a strategy, in exactly the same way as a street confrontation does tactically. Which is to say: there are consequences if you turn up and organize as a neo-Nazi, a neofascist extremist, a white nationalist, a racist. The consequence is: we will expose you. People who are organizing against you will make it clear that you won’t be able to get away with this by hiding behind a flag and then slipping away, or hiding behind a Pepe the Frog avatar. If you turn up to a white nationalist demonstration, we will happily reveal your name and inform your employer. It’s the same thing as saying we will confront you in the street. There are consequences. We’re not asking the state, we’re not asking law enforcement institutions to curtail your rights or reconfigure rights. We’re not asking for state interlocution in this. We’re saying we advocate local community organizing for there to be consequences for hate.

There are figures like the Daily News‘s Shaun King, who made it his business after Charlottesville to publicize the pictures of the five white supremacists who beat a young black man with metal poles and were not arrested on the spot (unsurprisingly). He made it his business to reveal them, to put their faces all over Twitter, and to find their names. That is classic antifa work which a Daily News columnist is committing himself to doing.

That’s a lot of the antifa work that people aren’t giving credit to. It has been important in revealing these Venn-diagrammatic circles that definitely go all the way to the white house, how these groups are organizing together and being and becoming together, from Spencer’s NPI to more traditional neo-Nazis to the hipster-thug Proud Boys.

CM: You write, “Figures like far-right leader Richard Spencer are the tip of a white supremacist iceberg that has been the norm since long before Trump’s ascendance.” What do we miss in our understanding of the far right when we not only see this as something new, but when opponents of president Trump believe that if we get rid of Trump, we’ll get rid of the rising far right, and that the far right is a historical anomaly that has risen under Trump and will go away after he’s gone? What do we miss in our understanding of the right when we embody it in Trump?

NL: We miss not just an understanding of the right, but an understanding of what undergirds the very conception of America and the very history of this country. This was obviously a former slave colony undergirded by white supremacy that has not ended. If we comfortably contain it within one persona or even a few extremist groups, we fail to address and recognize the struggle that was very present long before Trump arrived on the scene: the prison-industrial complex, standard-issue police brutality and impunity. Black Lives Matter did not arise under Donald Trump.

The idea that we’re addressing racism and that if we sever these extremists we’ll be in some post-racial utopia grandly disregards the struggle for racial justice that’s been going on without pause. That is particularly dangerous and would end up leading us to the very same problems that brought a Trump presidency about, the very conditions of possibility for it. That would be incredibly dangerous as an approach, and it would fall into the same logic that Bertolt Brecht pointed out in 1933: that the sort of antifascist who’s not willing to confront the capitalism from which fascism was birthed is like a meat-eater who doesn’t want to watch the butcher handling the meat. It would be incredibly foolish, and would be a rejection of structural problems, to place all our antifascism in a fight against Donald Trump or even just a fight against Richard Spencer and his neo-Nazi brigades.

CM: You write, “The alt-right is a fumbling, fractured mess. But support for racist ideology is not dwindling by virtue of this. Quite this opposite.”

If they are a fumbling, fractured mess, then why worry about the far right? Or does being a fumbling and fractured mess make them even more dangerous?

No antifa iterations, organizations, or upsurges are asking everyone to be willing to throw a punch. The ask is that centrists and liberals don’t throw the antifascists under the bus.

NL: Because white supremacy is so much of a norm, it doesn’t really matter if these groups—that keep having infights and are fracturing and decrying each other on their own blogs, websites, and Twitter feeds—fall out. There’s clearly an emboldened white nationalism, an emboldened white supremacy that allows for many groups to find each other and connect, and it plays into exactly what I was saying before. If we focus all our attention on just the named figures—be it Steve Bannon, Sebastian Gorka, Richard Spencer, or Gavin McInnes—and think if these guys argue each other into oblivion then we’re safe, then we’re not understanding that this is an emboldened ideology that is not going to go away without struggle, without confrontation.

CM: You write, “As with fascisms, not all antifascisms are the same. But the essential feature is that antifascism does not tolerate fascism. It would give it no platform for debate. The history of antifascism in twentieth century Europe is largely one of fighting squads like the international militant brigades fighting Franco in Spain, the Red Front Fighters’ League in Germany who were fighting Nazis since the party’s formation in the 1920s, the print workers who fought ultra-nationalists in Austria, and the 43 Group in England fighting Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. In every iteration, these mobilizations entailed physical combat. The failure of early twentieth century fighters to keep fascist regimes at bay speaks more to the paucity of numbers than the problem of their [direct, confrontational] tactics.”

So you don’t see the tactics as failing but a failure due to lack of participation? And if that is the case, doesn’t lack of participation, in a sense, reflect a failed strategy?

NL: It’s a double-edged sword. You might say if antifa tactics were less confrontational then it could draw a broader base. But I don’t think that’s an issue that cannot be overcome, so long as people are willing to embrace a diversity of tactics. No antifa iterations, organizations, or upsurges are asking everyone to be willing to throw a punch. The ask is that centrists and liberals (and even conservatives who themselves allege to decry these neo-Nazis and white nationalists) don’t throw the antifascists under the bus.

What we’re seeing in the days and weeks since Charlottesville is an immense amount of energy in the centrist media spent on decrying antifa. A lot of this paranoia and fear-mongering cites little more than low-level property damage. Spencer Sunshine, who is a longtime researcher, writer, and commentator on antifascism and fascism both in the US and western Europe, noted that if you take into account the last two decades in the US of fatalities related to far-right extremism as opposed to alleged “left extremism,” you’re talking a ratio of 450 to 1.

This speaks to the dangerous and ill-based false equivalency that Trump happily embraced. But the groundwork was laid by centrists conjuring specters and terms like the “alt-left” with little to speak of beyond some property damage at Berkeley and a few punches thrown. In the meantime we are seeing murderous actions from the far right and murderous intent from white supremacists whose very ideology is based on violent desire for genocidal action. So the idea of wanting to raise those people up to an equivalent equally worthy of paranoiac screeds in opinion pages is baffling and very discomfiting to me.

CM: There are a couple of ways in which this debate is being framed that you think are distracting and misleading, and it leads to a kind of a collapse of the discussion. You write at In These Times that “framing this issue in terms of free speech is a fallacy that cedes too much power to the state and other top-down institutions.”

How does a free speech framing cede too much power to the state and other top-down institutions? How much does free speech framing of this debate distract us from what you think should be discussed in this debate?

NL: Any time you start to talk about rights—constitutional rights, human rights—it’s a state discourse. The state gives or denies the rights that we feel we should be accorded. These are necessary to defend and discuss, but it’s always in a top-down framing. The fact of rights being accorded does not mean justice is established. It cedes too much to the right in that the suggestion that antifascists are asking state institutions to remove speech rights is a fallacy. It’s not in the anarchist tradition to ask the state to take up greater powers, even against perceived enemies of ours.

I think it’s a fallacy that this is the antifascist line, and when that fallacy is upheld, of course it undermines the idea of antifascism, because I agree: it would indeed be a potentially slippery slope if we start asking state institutions to take more and more control over who can or can’t speak. For example, there’s no right to punching Richard Spencer, though I certainly support that. So we have a very limited discourse if we only want to discuss what we may or may not have a right to do. We have to go beyond that if we’re talking about actually addressing these forces head-on.

I’m in Europe right now, actually; I’ve been in Berlin, and a couple weeks ago there was a neo-Nazi rally here. Really traditional neo-Nazis, not just PEGIDA, gathering to mark the anniversary of Rudolph Hess’s death. Very troubling stuff. And there are stronger hate speech statutes in Germany: they can’t have a swastika; they can’t carry bags when neo-Nazis gather; certain symbolism is not allowed; you’re not allowed to Sieg Heil. But nonetheless, they gathered. Nonetheless, they were there, and they were about a thousand strong—in Berlin, in this day and age! This speaks to the uselessness of demanding reconfiguration of hate speech statutes. Maybe it’s a good idea, but it really won’t get us to the erasure of neo-Nazis and their ability to organize.

It’s a bad focus, and one that liberals are very keen on because it makes both antifascists and fascists aligned with each other in their discrediting of institutional forces. But no, I have absolutely no interest in appealing to Donald Trump’s white house to change hate speech statutes, because authority isn’t in the habit of undermining itself, and I think Donald Trump is well aware that he is deeply enabled and supported by white supremacists and white supremacy.

Antifa action alone won’t bring us the change we need, but it never pretends to do that. It’s always part of a broader struggle, and I think if it’s seen that way it’s understood much better.

I also think if you look at the European models it hasn’t been a particularly helpful way of combating the extreme right. In Hungary they have strong hate speech statutes, and the extremist right is hardly having trouble organizing there. When we’re talking about something like the ability to deny the Holocaust, which is illegal in Hungary: that hasn’t stopped Holocaust deniers. What has stopped them gathering is when antifascists block their talks and make it impossible for attendees to get in, and make the speakers and the venues weigh whether it’s worth it. That’s why famous Holocaust-denier David Irving does not plan talks anymore throughout the United States. It’s not because of hate speech statutes; it’s out of an awareness that he will be met en masse with antifascist action.

CM: Why isn’t the best strategy to get as many leftwing speakers—those who effectively argue against neo-Nazism, fascism, and the far right on campus—convincing the student body on college campuses that the left has the superior message? Why not cede space to the far right and win with arguments?

NL: I don’t think this is based on rationality. I don’t think the reason the far right is gathering and gaining ground and traction is because they have compelling arguments. It’s a sentiment. It’s a ressentiment that is not the sort of thing you can argue someone out of. It’s a different sort of experiential phenomenon.

By the same token, there’s no point at which I think, “Oh, so you’re a racist and I’m an antiracist, but please, tell me about your racism.” This is also part of the free speech fallacy. Think of someone like Milo: he’s not putting forward an argument. He’s gathering and playing on ressentiment. The idea that this can be challenged by polite debate doesn’t understand what’s fueling it. This is not a problem of ideas. If it were, then the contradictions and the idiocy of this sort of racism and extremism would—a bit like the internal contradictions of capitalism—collapse on itself. But like the internal contradictions of capitalism, it actually takes struggle to bring it to a close and to overturn it. It’s the same, I think, with this racist ideology.

Its own idiocy does not, empirically or historically, argue itself into oblivion, and nor does a polite debate with that sort of ressentiment and that sort of hate end in a positive win for the left or for justice. I wouldn’t give these sorts of ideas credit as counterpoints. They are not counterpoints.

CM: One of the things I couldn’t help but think about while I was reading your work is how climate change denialists became legitimized by giving them the same due as actual climate scientists who were telling people that climate change was actually happening. All I could think of was fascists being allowed to have that same seat within the media. I started thinking of the frustration that people on the left have had with that kind of thing, but it goes beyond that. Affirmative action, Brown v. Board of Education—they didn’t work. Corporate consolidation has silenced everything but rich, rightwing perspectives.

How much does the antifa movement reflect a foundational frustration with a broken system—whether it’s the media or the government—that no longer works for the left?

NL: I think it definitely represents frustrated people, but “frustrated” doesn’t go far enough. It’s rage. It’s righteous rage. If frustration becomes ennui and acceptance, that’s one thing. But antifa doesn’t carry the same valence of frustration, because it is a mode of getting together, organizing, networking, finding each other, and using rage. Frustration has little practical use. This is a tactical approach that has tactical efficacy, which is not a particularly frustrating thought to me.

Antifa is part of a broader revolutionary idea, which is also related to prison abolition and true liberatory justice. I definitely think it would be pretty frustrating if the only thing we can do is shut down Nazi rallies. Antifa action alone won’t bring us the change we need, but it never pretends to do that. It’s always part of a broader struggle, and I think if it’s seen that way it’s understood much better.

CM: Natasha, I really appreciate you being on the show this week and being able to have this conversation about the context and history of the antifa movement; I think it was desperately needed. Thank you so much for being on the air with us today.

NL: Thanks so much.

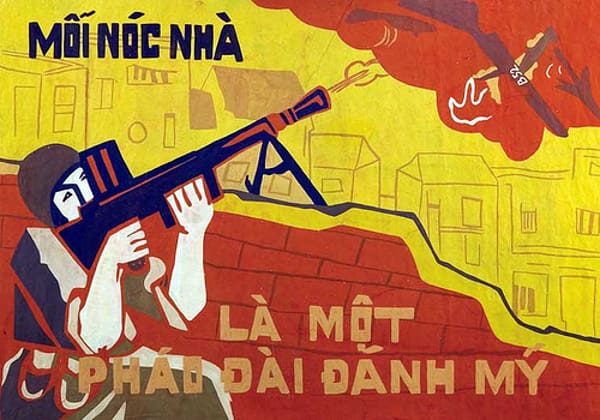

Featured image source: Great Lakes Antifa (Facebook)