It Doesn’t Have to Be Like This

Spending time among Russian antifascist punks taught me a political—and very personal—lesson.

By Benjamin Herbert

3 October 2017

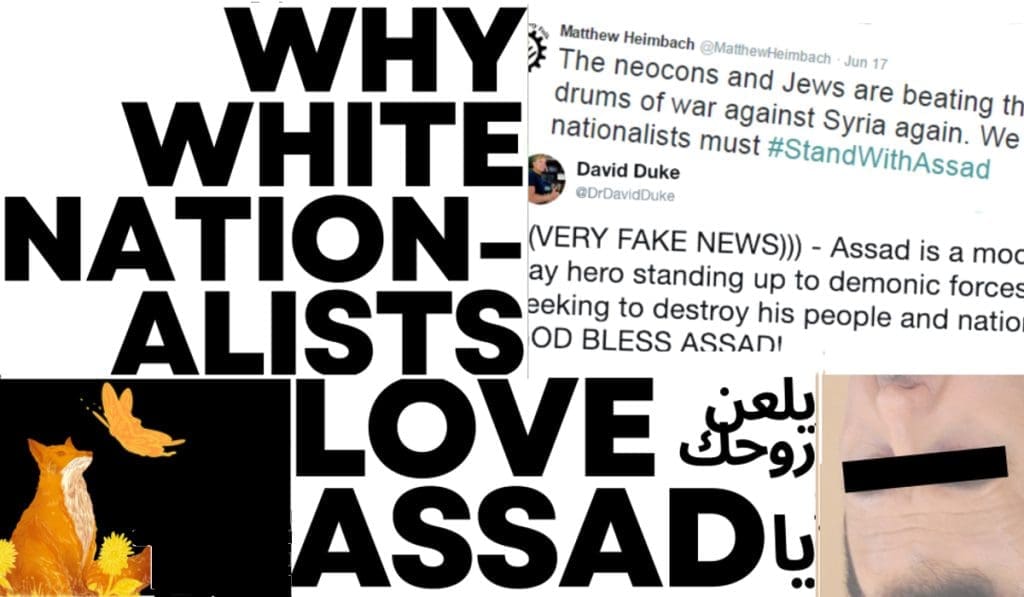

In August, a group of white supremacists and neo-Nazis gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, ostensibly to protect the monument of confederate general Robert E. Lee. A few days later, it was reported in the Richmond Times-Dispatch that the widely-circulated New York Times photograph from the rally of James Alex Fields—the white nationalist who would ram a car through a crowd later that day, killing Heather Heyer and injuring others—had also been used to out the man standing next to him, a certain Nigel Krofta. In the photo, both of them are wearing white polo shirts, a symbol of the alt-right modeled after President Trump’s golfing attire.

Nigel is—was—one of my best friends. He had been one of the first of our group of friends to escape our small Massachusetts town when he moved to South Carolina a few years ago. He was looking to make it on his own in the South, where, he had heard, there were enough welding jobs to keep him busy. After he moved, I had kept in touch with him through Facebook and frequent late-night phonecalls. Initially, our conversations consisted mainly of him bemoaning his roommates and regretting his decision to move down there. It was clear that he missed his friends back home, but he also seemed to be fascinated with the stereotypes of white males in the south, and for a while we used this for comic relief; it seemed to ease his growing feelings of isolation. Gradually, however, the jokes started to shift from satire to reality. I started to notice a disturbing change in the way he described his interactions with people.

One night, he started telling me his views on national socialism and the Holocaust. He claimed that national socialism (emphasis his) was just a form of “nation-based socialist utopianism,” and that the Allies had eliminated Nazi Germany because national socialism was contrary to Western democracy. He said that the Holocaust had been fabricated by Western Jews to moralize democracy’s claims against the “advances” of national socialism.

Disturbed, I cited academic articles and books regarding the ideology of national socialism as well as the truth of the Holocaust; I sent him links to Holocaust survivors’ websites—which he disregarded for having been written or published by Jews. I reminded him of our childhood friends who are Jewish, black, hispanic, Asian, and Indian. “Could you really tell me that you would have been happier without the company and camaraderie of X?” I asked. His inadequate responses could be summarized thus: “I don’t believe they should be exterminated, just that they should live somewhere else—each ethnicity should have its own homeland and stay there.”

Although his conversion seemed sudden, for us these ideas were far from new. Coming of age in a small town punk rock scene in the 2000s, we had been aware of these outlandish ideas and conspiracy theories at a young age—not because we espoused them, but because we had actively combated them. In high school, Nigel was a self-proclaimed anarchist, communist, socialist, and all-around idealist searching for an identity, aching for people to take him seriously. He once confessed to me that his biggest wish in life was to lead a popular uprising like Vladimir Lenin had, but he was embarrassed to admit it. It was, after all, an extremely naïve wish.

When he started openly espousing new political views years later, his previous politics were why I didn’t take it very seriously at first; I was pretty sure he could be coaxed out of his ignorance. I even thought it might be a prank he was playing on me. Never willing to fall for a joke, I decided to start writing a satirical article cataloging his developing bigotry—it seemed like every time I talked to him he became more outlandish, more elusive, and more caught up in stereotypical Southern racism. All of us Northern boys back home joked, unthinkingly, about how Nigel was changing into a caricature of a Ku Klux Klan member. This was before Donald Trump was even a presidential candidate, when people of our age and station still thought the KKK only existed on the History Channel.

The night we shared a drink over the phone and argued about his views, I had gone to bed thinking my defense of free choice, diversity, and “multiculturalism” (as he called it) may have resonated with him. I didn’t believe I had fully changed his mind, but I felt I had at least played my part in trying to persuade him. Ignoring it obviously hadn’t seemed like an option, because this was my best friend—someone I had played in bands with, shared experiences with, and identified with. At the time I still cared about him deeply. After I hung up the phone that night, I went back to my life, content in having played my part. At the time, he was working a menial job, barely making ends meet, and sleeping in his van—I thought it was only a matter of time before he wised up, or, ideally, moved back home.

And Then There Was Russia

Time went by, and I became more and more enmeshed in my academic work and personal life. In the summer of 2017 I went to do research in St. Petersburg, and used the opportunity to conduct more interviews for a book I had been working on about the history of Russian punk rock. Coincidentally, the bulk of the interviews I conducted were with past and present members of Russia’s antifa movement.

The movement in its current form can be traced to the fall of the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, Russians were awakening to their new ability to express their political views openly, and high profile bands like Distemper were beginning to take a decidedly leftist stance against neo-Nazism and in support of anarchism, communism, and socialism, like many Western punk rockers. Nonetheless, isolated members of Russia’s burgeoning punk rock scene embraced right-leaning politics, citing the former Soviet Union’s failure as a testament to the inefficacy of leftism. Russia’s frail economic and social conditions in the nineties exacerbated the popular disdain for leftism, and the influx of post-Soviet immigrants from Central Asia pushed their political views still further right, until they eventually evolved into a Russian incarnation of neo-Nazis.

Neo-Nazis relied on Russia’s then-new Internet access to replicate nationalist paradigms, rhetoric, and tactics from other countries. As the nineties turned into the aughts, rising neo-Nazism was further augmented by the Russian Orthodox Church’s expanded role in the public sphere as well as by the new Putin regime’s nationalist sentiments surrounding the Chechen wars. Russia’s extreme right became a powerful political force, and they had grown so defensive of their views that it metamorphosed into outright offense—they raided punk concerts, jumped innocent people, and called bomb threats on shows. Along with the reign of terror they launched against immigrants, ethnic minorities, and queer people, they specifically targeted punk because they felt banished from a scene they had once belonged to, and they knew that punk rock was a refuge for leftists, homeless people, drug addicts, and social outcasts. It was a potentially vulnerable scene. Russian punk was also extremely multicultural, consisting of adherents from Kiev to Vladivostok, Uzbekistan to Vorkuta.

According to one scene member I spoke with, by around 2004 it seemed like Russia’s punk scene was destined to fall into utter obscurity, with bands incapable of publicizing their shows or even playing concerts without fear of their fans getting beaten up outside the venues. But punk rock, broadly defined, is an enduring subculture and identity, and the violence being exerted to keep the scene down also started to breed serious resentment and regret. Furthermore, Russia’s punk generation of the 1990s had started to cede the stage to a new generation of kids who had not experienced the Soviet Union but had only lived in the economic stagnation and dislocation of the Boris Yeltsin years. This new generation needed to believe in something—needed to think that someone believed in them—and began to channel their anger at the state into a new form of coordinated radical leftism. More importantly, they sought to reclaim their own space to freely express themselves.

Ambitious youth who sincerely believed in punk rock as a safe space for both the apolitical and radical left literally began to fight for their right to exist in public, play shows, and attend clubs. Not everyone sought violent encounters, but there were a few who patrolled the streets outside gigs, broke up neo-Nazi concerts, and protected their friends. Neo-Nazis had to learn that there were people willing to match their violence fist for fist. More fundamentally, fights were less important than the possibility of a fight. Neo-Nazis needed to see brigades of antifa; they needed to face the same fear they imposed on their victims.

Activists also began tracking neo-Nazi blogs and reading up on their tactics; they left comments and counterarguments on white nationalist web pages; they unleashed a barrage of counter-propaganda. If someone was unwilling to either fight or write, then music provided another mode of promoting the ideas of antifascism. The coordination of the movement and its determination to reclaim a safe space for social outcasts set an example for young punks entering the scene.

One antifascist I talked to described their activities as a type of “mental violence.” The goal was to infiltrate neo-Nazi resources and plant “mines” of information. Don’t insult a Nazi or talk down to them, he said—that’s ineffective and in most instances counterproductive. Simply make the correct information readily available to them, have clear and articulate counterarguments, and never “agree to disagree.” Antifa DIY zines with names like antifashistskii motiv began to circulate, and word spread that Russian punk rock—the bands, the venues, the fans—were not going to stand idly by and watch their scene get stamped out.

There were instances of serious violence. In 2005, a group of neo-Nazis stabbed antifascist Timur Kacharava to death, further embroiling the antifa movement. Brigades of antifa activists began leading regular “marches”—or, more aptly, patrols—on the streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg between 2005 and 2008, which further provoked neo-Nazis and racists. In 2009 Ivan Khutorskoi, an antifa activist nicknamed Bonecrusher (because he “crushed” boneheads, a slang term for neo-Nazis), was shot at point-blank range outside his own house by a member of the neo-Nazi group Boevaia Organizatsiya Russkih Natsionalistov [BORN].

Many of punk’s defenders belonged to the skinhead subculture (RASH or SHARP branches in particular—anti-racist defenders of the traditional skinheads), so they saw themselves as defending not just a space but an identity (similar disputes over contested cultural trappings had parallels in the West and continue today in new forms). They were effective, but unfortunately this efficacy made neo-Nazis desperate and thus arguably more dangerous.

One former leading figure within Moscow’s antifa movement told me that he feels personally responsible for the murders of Timur and Ivan, because they had made neo-Nazis so uncomfortable expressing themselves publicly that they started to resort to acts of cowardly violence. He might be right in one sense; the Nazis were definitely feeling the pressure. Kids willing to fight back and defend their artistic spaces were squeezing Nazism out of the public sphere. Nevertheless, Timur and Ivan knew the risks of their activism, and volunteered anyway.

Ivan and Timur did not have to die—should not have died—but to this day their deaths are memorialized within the scene. Without their activism and sacrifice, Russian punk would not be what it is today, with its plentiful shows, energetic scribes, and thriving online culture. It would have descended into rightist obscurity, and that process would likely have cost the lives of many, many more innocent people unwilling to accept a bigoted understanding of punk rock and of the world. Eventually, antifa’s social programs like Food Not Bombs and the annual United Help Festival, counter-propaganda efforts, and music outreach eliminated the threat of neo-Nazi provocateurs at concerts. Many former activists see the time as the ultimate test for Russian punk rock; its endurance gave them a right to exist. When they attend shows today and see kids having fun, they can’t help but swell with pride in what they helped establish. Punk rock is a safe space for social outcasts and leftists in Russia today because antifa defends it with a variety of tactics including doxxing, trolling, hacking, social advocacy, and, when the situation calls for it, violence.

Neo-nazis exist in Russia today, but they are more or less confined to online agitation and comment sections; they certainly don’t invade punk rock spaces anymore. Russia’s various radical rightwing and neo-Nazi groups have been listed (along with antifa, it should be noted) as terrorists by Russia’s Department for Combating Extremism, or Center “E.” However, although this designation was accompanied by heavy repression in some cases, the authorities in practice also handed other extreme rightists a new disguise in the form of acceptable Russian nationalism (whereas antifa, of course, has no alternate state-sanctioned identity to hide behind). Today, Russian antifa combats Russian nationalism cloaked as pro-Putinism, rather than public displays of open Nazi sympathy. This allows the government to label antifa as criminals, while leaving many nationalist ideologues with the ability to present themselves as “patriots.” Sound familiar?

Good night white pride You keep silence, while they shout, They are heard, and you are not. Do not sit aside, Do not obey stupidly. With your inactivity you dig a grave for yourself, Now you do not care, but it will also concern you, Fascists will never know rest until you show the strength, Resist, speak aloud about your views. GOOD NIGHT WHITE PRIDE! Has fascism already become a norm? Did YOU forget, what millions of people died for? Do not dissemble the problem of Nazism, Do not believe in all these ravings. GOOD NIGHT WHITE PRIDE! —What We Feel, “Good Night White Pride,” off the album Last War (2007)

Since the events in Charlottesville, many observers who decry antifa’s willingness to resort to violence (but are largely silent on racist violence) have underrated the usefulness of the movement to the long term effort of combating bigotry in America. This inconsistency has the effect of allowing one group’s exercise of free speech to consist of literal murder, while radical leftism is chastised by its own ostensible allies for much, much less. And for participants in Black Lives Matter, black bloc, and antifa in the United States, this is not simply a matter of “free speech,” it’s about survival.

Liberals and centrists are not maintaining the moral high ground by declaring violence wrong and discouraging their radical cohort, they are simply empowering people like the guy in this video, who already sees the left as weak and couldn’t care less what they say. Indeed, in the world of President Trump, the youth’s sense of morality has significantly shifted on both sides of the political spectrum; the election precipitated a realization on behalf of millenials that our parents and grandparents can no longer define our moral standards. That creates an imperative on behalf of Democrats and progressives (particularly the elders) to refrain from contributing to the marginalization and repression of direct action groups with knee-jerk public denunciations. When push comes to shove, many of these groups want the same thing as those pleading for nonviolence.

This is not to say that we have to accept violence as normative political action, but we have to be careful about who we marginalize through our opinion pieces, and who we are implicitly empowering. White supremacists are free to say and believe what they want, but public space—the streets, as we say—should not be surrendered to them simply because pearl-clutching American liberals disapprove of radicals opposing them assertively.

Whose Streets?

In fact, the centrality of public space remains one of the fundamental misunderstandings between antifa and nearly every other position on the American political spectrum. In a recent article, Nathan Robinson argues that violently resisting white supremacy is counterproductive to the elimination of Nazism because uncoordinated, random acts of aggression only inflame alt-right arguments and actions. This is true. It should be noted, however, that few antifascists believe ideology can be systematically eliminated for good. The struggle is concerned with defining public space, in making it clear to white supremacists that their ideology and idols have no place in the public sphere—not in debates, not in public parks, and not on public streets.

As one anarchist media collective historically supportive of antifa has recently written, “[anti-fascists] must make it clear to the general public that we do not intend to impose a new dictatorship, but only to open and preserve spaces of freedom.” If you believe that the end goal of antifa is to limit free speech, you simply do not understand the movement.

As far as Robinson’s article goes, sources speak volumes. He makes reference to antifa activists in Boston and Charlottesville allegedly engaging in non-defensive acts of violence (arbitrarily pepper spraying Trump supporters, and yelling “GET THE FUCK OUT OF MY CITY!”). Sure, these acts are embarrassing for the left and can be used as news fodder on Breitbart, but who cares? Even the most obscure rightist movements have always had (and always will have) their megaphones. Besides, screaming obscenities at people is a form of hooliganism that cannot realistically be compared to the death threats and murders committed by neo-Nazis.

Entirely eliminating neo-Nazism and white supremacy is an unrealistic dream, but limiting its reach and its appeal, discrediting its “news,” and restricting its access to public space are real tangible goals. If that effort is carried out systematically, then whatever trumped-up allegations alt-right and neo-Nazi news outlets use against the left become superfluous. Robinson has merely articulated a classic leftist misunderstanding more cleverly than usual, he still dismisses antifa too quickly. If he considers them childish, perhaps his intellect would be better used to guide rather than further divide the left.

American leftists need to understand and agree to the terms by which white supremacy must be confined, rebuked, and combated. Violence alone was not what made Russia’s antifa movement effective in eliminating neo-Nazis from the punk scene. It was a concerted and multifarious effort of writers, theorists, and fighters teaming up to drive Nazism back into obscurity. If some in the American left don’t approve of antifascists’ tactics, don’t put them in danger through performative distancing and denunciation—help them make their protest more effective, help them channel their willingness to punch into useful acts of defense.

In the words of an antifa favorite Peter Gelderloos, antifa is willing to work with a diversity of tactics that should be “chosen to fit the particular situation, not drawn from a preconceived moral code. We also tend to believe that means are reflected in the ends, and would not want to act in a way that invariably would lead to dictatorship or some other form of society that does not respect life and freedom. As such, we can more accurately be described as proponents of revolutionary or militant activism than as proponents of violence” (Gelderloos, 2007. How Nonviolence Protects the State. Brooklyn, NY: South End Press).

Don’t assume that the value of antifa begins and ends in violence. Embrace their passion, as well as their tech savvy, and welcome them in the effort to maintain the inclusivity of our public spaces. They are literally the foot soldiers of the left, who have proven that they can infiltrate alt-right media outlets and plant “mines” of counterinformation among their family members, friends, and former friends. These are the same people who have identified neo-Nazis involved in the Charlottesville riots and exposed alt-right chat logs.

Instead of debating whether the Civil Rights Movement succeeded because of the fear or absence of violence, we should be making use of the various skills and passions among us to reach a broader audience, to combat the conspiracies and misinformation that floods outlets like Breitbart and, not coincidentally, RT. If you choose to sit behind your keyboard and pontificate against the leftist use of violence, you are underrating the experiences of those for whom nonviolent protest has failed. You are overlooking the obvious fact that those at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville clearly came to hurt people. You are insulting those of us who have tried peacefully to engage with bigots. You are ignoring the fact that your personal safe places are not the same as everyone else’s.

One might say such liberal pontificators are incapable of seeing or imagining the real world outside their bubbles…which, it bears mentioning, is partly why the alt-right now has a President they can admire.

In other words, when the violence of neo-Nazis and bigots starts to impact your homes, your streets, and your government, it’s past time to deploy every resource available, and to tolerate, even grudgingly, those willing to do what you are unwilling to do. When neo-Nazis confront nonviolent protesters with weapons, and attack and murder brown people in the streets and in their private spaces, then it’s past time to let the “radicals” among us defend our collective right to free speech. If that happens, if we manage to “Unite the Left” in such a way, then in the words of Woody Guthrie, fascists are bound to lose.

Understanding and Containing the Threat

Needless to say, passive-aggressive debate with Nigel was not enough to sway him to my side, and no number of articles and sources could convince him to think twice about his views. Since his picture circulated, he lost his job and his own extended family has denounced his actions. People around him report hearing in his rhetoric a ”sheepishness” that still recalls his struggle with identity, his desire to belong somewhere. This is not an effort to humanize him, but to warn that he—along with many more who share his political views—has little left to lose.

Our local town newspaper in Massachusetts ran a story about him, and when they posted it to their Facebook feed many people who didn’t know Nigel referred to him as a “privileged white boy” in the comments underneath. This is correct, to the extent that Nigel is white: he’s never had to experience the repercussions of his words, never had to know what it feels like to be despised simply because of the color of his skin, or the religion he practices. He’s never confronted systemic racism, and might not even know what it entails.

But these claims of “privilege” are wrong in the sense that privilege also implies some form of belonging—to a family, class, club, subculture, or nation that maintains a special place to freely be oneself. He barely knew his parents, denounced class, sought something more public than punk rock, and found identity only in some abstract, misinformed understanding of a nation. Nationalism has been his first form of identity, and clearly he is willing to fight for it.

How do you rid somebody of that without physical or “mental violence?” My ex-friend is certainly not an archetype for all white supremacists, but he is an indication of the power of ideology and identity, something that too many people take for granted (and something that fascists utilize in their recruitment strategies). Identity like that cannot be talked and argued out of the hearts and minds of people. History books suggest that it can only be forced back into the shadows (if you doubt that, I recommend reading the rest of Gelderloos’ work).

It’s not every day that Russia has something to teach the United States. I believe we can learn something from the tactics and methods of Russia’s antifa. They were effective because they agitated in a purely defensive fashion, focused their tactics, demonstrated a willingness to use violence only incrementally, and pooled their resources and skills together into a concerted effort to eliminate hate. They banished neo-Nazis from public spaces, deployed their fists, and overwhelmed their enemy with counterinformation, infiltration, and doxxing.

As long as centrists and progressives on what passes for the American left continue to denounce direct action groups, they are marginalizing their most tenacious allies and putting them at risk of more arbitrary police and rightist violence. The American left is tasked with finding a position that does not alienate the energy and determination of the youth, because ultimately we need them in the fight to protect public space and the public good from those who embrace bigotry.

The forthcoming work referred to in section two is What About Tomorrow: A History of Russian Punk, due to be released by Microcosm Publishing in 2018.

Featured image: The author with Nigel Krofta in 2012