Transcribed from episode #2 (“An Intro to the Yemen Conflict”) of Irrelevant Arabs and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Audio no longer available.

In the end we managed to get in. I don’t think any other journalists have managed to get into Sana’a after us. There’s obviously a media blackout.

Mustafa: Hello everyone, and welcome back to the Irrelevant Arabs podcast. Today we’re here to speak about Yemen, a topic that has been eluding everyone in the international media, and very poorly covered.

Loubna Mrie: We have with us Sara Obeidat, who is a close friend of mine and a brilliant journalist. Sara is from Jordan, currently based in New York, and she is working for Frontline. She recently came back from Yemen; she was producing a documentary there. You should all watch it.

And on Skype we have Afrah Nasser, who I didn’t meet yet, but I kind of stalk her on social media, and I have a huge crush on her work. Afrah is an award-winning journalist and human rights activist.

We just had—not an argument, but you corrected me when I said “human rights activist,” so I want you to tell me why you don’t like to be called a human rights activist.

Afrah Nasser: First of all, I’m very delighted to be in this group talking about Yemen, my country, which is going through a devastating war just like Syria. Usually I introduce myself as a journalist and human rights blogger, not an activist, because my activism is mainly about writing. Most of my writings are about human rights issues or politics.

This is also a chance for me to send a message to other bloggers that they can use this platform to speak about things that the international media doesn’t talk about, or where they feel not well enough represented in international media. My blog is the love of my life, because the love and support that the blog has gotten is beyond what I could imagine. It’s very dear to my heart, and that’s why I call myself a human rights blogger.

LM: Afrah, if you could describe one main issue you have, or one main problem with the international media or the way that the media is dealing with Yemen, what would you say?

AN: Loubna, the first time I got to know about your writing and your work was when you wrote about something that was causing the lack of media attention on Yemen: the problem of Western “Syria experts.” At the time, I was also thinking about the same issue, and I wrote about the problem of “Yemen experts,” but you were more eloquent and stressed the fact that it was Western “Syria experts.”

From my experience as a Yemeni journalist, I honestly didn’t imagine that I could ever get recognized for my work. I always thought I didn’t have the same entitlement that Western experts have when they speak about our countries’ issues. In my opinion, when outsider “experts” talk about the sufferings of people in the Middle East (take Yemen or Syria), and native commentators are not given the same level of space in the media, of course there is going to be a certain domination of one perspective, and that’s usually the Western perspective. It’s really unfair. If there were a better-informed audience getting the picture from local, native journalists or experts, maybe we could have solved the problem (when we speak about discussing those conflicts on the international level).

That was something that made me start the blog: I thought there were not enough Yemeni native voices talking about Yemen to the international community.

M: Throughout the whole Syria dilemma, from 2011 onwards, when I read articles that were written from the Western perspective, it always seemed like their base of reference was always the Western world. When someone would write an article, for example, about the imprisonment of an activist, they would say this activist was imprisoned without access to a lawyer, and I would think: ‘How far is their knowledge from the reality of our part of the world, where access to a lawyer is such a luxury?’ Not only a luxury. The authorities never really care about that. And I think, ‘Wow, these people who are writing about us actually think that if we got a lawyer that that would solve the problem.‘

AN: But Mustafa, you know, every time I have this conversation I try to say that I’m not dismissing the importance of academics and scholars from the Western world. It’s just, can we have a fair space for both perspectives? From both the local and the scholars’ perspective? We normally don’t have the privilege to bring our own perspective or the knowledge that we have as someone who’s from that region, from that country, from that city. You don’t usually find two commentators, one from the country and one from the Western world. What I want, really, is not to dismiss any side. It’s just better to have a fair and just representation.

LM: I completely agree. In the first episode with Yassin al-Haj Saleh, we said we are not trying to tell people not to talk about Syria, but that people have to understand that we are equal, and that we have something to say, and we have our voices and they need to be heard. Like, do not be the “voice of the voiceless.”

We also have a non-Yemeni person with us today, but I love her work, and she did a great a job when she went to Yemen, so maybe Sara can tell us more about what it was like to go to Yemen. Maybe you can also tell us about the process: how were you able to go there, and why do you think that not many journalists today are able to travel to Yemen and cover what’s going on?

Sara Obeidat: Before I start that, I also want to piggyback on this point. I also see this when I’m working with Western media. And it’s why I find it so refreshing to work with other Arabs, when we’re working on the Middle East. Without trying, a lot of Western journalists want to fit things into categories. Partially it’s because the nature of the practice can sometimes be simplistic. They want their audience to understand. And partially it’s because they are trying to make sense of it themselves, too. So it always ends up being Sunni versus Shi’a or Palestinian versus Jordanian. People want to put you in boxes when they’re writing about the region.

There have been a ton of times where I’ve read articles on Jordan, and if I didn’t know anything I would think there were Palestinian tribes at war with Jordanian tribes. It’s because of the way things get explained. That’s one of the reasons why having more Middle Eastern or Arab journalists on the ground is so important, because we challenge that, and bring more nuance, and the conversation becomes much more sophisticated when you have us participating.

Ali Abdullah Saleh was willing to give up power, but he never gave up politics.

As for the process, it was honestly really difficult to get in. The Saudi-led coalition is actively blocking journalists from entering Yemen. Afrah, you can probably correct me on this, but I think in November 2016 the Saudi-led coalition spoke to the UN and told them: you will no longer be bringing journalists with you on your flights. The issue is that the Saudi-led coalition controls the airspace over Sana’a. That’s where the airport is. They bombed the airport, and no commercial flights are allowed to come into Yemen. The only flight that gets into Sana’a is a United Nations flight. That flight usually carries cargo, it carries UN personnel, it carries aid workers.

Although the UN sees the value in having journalists report on the ground, having their flights delayed or grounded or stalled because they’re trying to get journalists in isn’t really efficient for them. So in a way, their hands are tied. When they want to fly in, they send the list of passengers to the Saudis for final approval. Supposedly they’re sending it to the coalition; supposedly they’re sending it to the Yemeni government-in-exile, and the foreign minister approves it. But at the end of the day the Saudis can say, “No, we don’t want X, Y, and Z on this flight.” And the United Nations have no choice but to take you off.

So when we started the process, we realized that getting into Yemen was going to be a full time job. It took me three months of consistent daily phonecalls, whether it was with embassies or the UN or the Yemeni government-in-exile or the Houthis. We needed to apply for two visas, as if we were going into two different countries. We needed a visa from the Houthis, and we needed a visa from the Yemeni government-in-exile.

Then we had to go to Djibouti and just wait and see when we can get on a flight. This was actually quite funny, because we were scheduled to get on a flight, and then at around eleven p.m., one of the guys from the UN (who had at this point memorized my voice) called me and said, “I’m so sorry, we thought everything was fine; you had your visas; we want you to come…but you’re not allowed to board the flight.”

After pressing and asking why (and of course he didn’t want to explain it), in the end he said, “Look, it’s out of our hands. Please understand. We want you to come. It’s not really our decision. Your names aren’t approved on the manifest.” It was a bit of a disaster for us.

But it just so happened that we had been in Saudi Arabia a few months before. As we interviewed officials, we asked most of them, “Why are you preventing journalists from getting into Yemen?” A lot of times, they would say, “We’re not preventing journalists from getting into Yemen. You can go, of course.” A lot of those people had given us their word, whether it was on camera or off camera, that of course we can get into Yemen. Other people said, “It’s for your safety. If we can ensure your safety, then we’ll let you go.”

So it was really easy to just call all these people that we had interviewed before, and say, “Hey, remember that? We’re being prevented by your government from entering.” And in the end we managed to get in. I don’t think any other journalists have managed to get into Sana’a after us, except for another Yemeni who works for the BBC, and she had to take a commercial flight and then drive eighteen hours to get to Sana’a. So there’s obviously a media blackout.

M: The problems that come out of the UN in the Middle East today are also something that should be covered a lot. Their answer is always, “We are trying; if we weren’t to cooperate with these governments then none of the aid would ever get to where it needs to go.” But it feels like their hands are always tied, and it empowers the governments like the Assad regime or the Saudi-led coalition to control anyone. They can stop journalists from coming in, and they’re blocking an international organization that’s supposedly as powerful as the United Nations.

And the first rule in aid, in my dictionary, is that people have to know the story to be able to help.

SO: We spoke to several UN officials working in Yemen. Almost all of them expressed their frustration with the coalition. I can’t really blame them, because I know that funding is always an issue.

More attention should be given to the US, which is empowering the Saudis to behave this way and bullying the UN into this. The Netherlands, at the UN, suggested that an independent body be formed to investigate the war crimes of the coalition. The Saudis, with the help of the United States and the UK, blocked that motion, and instead helped the Saudis say, “No, it’s okay. Our coalition will form a political body that will investigate the war crimes.” So we have the Saudis investigating Saudi war crimes. It’s called the JIAT [Joint Incidents Assessment Team], and the US and the UK were totally on board with that, and blocked the Netherlands’ suggestion to have an independent body.

I don’t think the focus should be on UN employees or the person who’s trying to run the UNHCR in Yemen. We should be putting more pressure on the United States and the United Kingdom, who enable the Saudis to behave this way. I have never heard of a party at war that dictates the airspace to a UN aid organization and can say who can come in and who can’t.

LM: Let’s say that someone is listening to this podcast and the last thing he heard about Yemen is that there was an uprising back in 2010. Afrah, how did the situation become this bad?

AN: To summarize it and to make it as simple as possible (but trying to include everything that happened since 2011 especially): we got here after going through three main phases. One: in 2011 there was the Arab Spring, and Yemen joined the movement and there were thousands and thousands of youth who took to the street. There was a youth-led uprising in Sana’a, in Ta’izz, in Hudaydah—in so many cities. That was the spark of where we are today.

Ali Abdullah Saleh, who ruled Yemen for more than thirty years, was eventually overthrown, and his ex-vice president, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, who is the president we have today, came in as a transitional president. Ali Abdullah Saleh was willing to give up power, but he never gave up politics. He was still there, and he signed a deal transferring power to Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi—with a lot of conditions. I don’t understand how you could ever give a dictatorship the chance to leave power under its own conditions. That was one of the biggest failures that we had right there.

And then there was the second phase: it was mid-2014. There was a political component to a religious movement that had started as early as 2004. It was led by Abdul-Malik Badreddin al-Houthi, and this political-religious movement, at its core, calls for the revival of the imamate that ruled Yemen during the fifties and sixties (which was overthrown by the ’62 revolution).

The Houthis wanted to hijack power from Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, and they invaded a lot of cities and took power of the capital city, Sana’a, and chased Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi to his place in Sana’a, then bombed it, and when he escaped to Aden, they also followed him to Aden. They wanted to have total control of the whole country. He was looking for any kind of exit or support, and that’s why he fled to Saudi, and Saudi Arabia was willing to “intervene.”

At that time I thought it was going to be just a two weeks’ intervention that started in March 2015. I thought it was going to be really quick, personally. I never imagined it was going to last until today.

Those are the main defining moments of where we are today. But in my opinion, what Sara was explaining about just how challenging—or sometimes impossible—it is to get into the country, and the many authorities that you have to contact to find a way: that, for me, represents the fragmentation of Yemen. It’s power struggle. The Saudis want to have their say. The Houthis want to have their say. Adi Abdullah Saleh is still a key political influence in the country. And there is also Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, whose function was a temporary one, but he’s still holding power and is not leaving.

Growing up, I never thought that terrorism, what the US is speaking about, was a priority for me. Poverty was the terrorism that I knew.

So you have all these political players. It’s limbo for everyone. At the same time, the country is getting divided, and divisions are growing. The Ma’rib region is having its own control. Hadhramaut has also been battling with Al Qaeda—they want to have their own control. And then there is Ta’izz, which has been under siege for almost two years now, and there are growing divisions between the resistance groups. So basically a whole country is melting in front of us. That’s the biggest political devastation caused by the war; it is prolonging the conflict, and I don’t see any end in sight.

M: Everything you’re saying reminds me of the importance, when talking about the conflicts that are going on in the Middle East, of always putting them in a historical context. For all those divisions that are currently happening within Yemen, all those power struggles, when the Western media brings them to the screen or to the newspapers, it always seems that they’re taken out of context.

It’s as if 2011 was the start of something that just happened in 2011, while the reality is that foreign influence in supporting Ali Abdullah Saleh and other Arab regimes has led to a lot of these divisions and sectarian conflicts being seeded into our communities. We know that Ali Abdullah Saleh always used these inner tribal conflicts in Yemen (and the “war against Al Qaeda” and all of that) to sustain his power, and we know that he attained funding for that from America and from the rest of the world.

Now, today, when people talk about all these divisions in Yemen and Syria and Egypt and Libya, they’re always just talked about from this context of, “Well, that’s only logical for the Arabs to start fighting each other right now, because this is how we are.” No, this is an outcome of a long history of influence that is supporting dictators and propping them up, knowing very well that they are turning their people against each other and systematically destroying our education systems and our infrastructures, so that one day, when we do rise up in a real revolution to change our status quo, we will be shot down because of this massive disease that they have spread into our societies.

Everything you said reminds me so much of what’s going on in Syria. The only major difference I see is that thankfully Syrians have been able to escape to neighboring countries—a lot of them have, anyway.

AN: That’s a very important point to emphasize, because the cruelty of Yemen’s war is that it is the poorest Arab country surrounded by some of the world’s richest countries—and most of them are bombing this country. There is famine unfolding in Yemen, and just a few kilometers away there are people living extravagant lives. That’s the contradiction of why this is happening to this country.

But of course, as you mentioned, it’s very important to talk about the global and international relations impacting the trajectory of these conflicts. Yemen, as I said, is the poorest Arab country, and today is having the largest humanitarian catastrophe—and I remember in the first four months of the conflict, a person from the Red Cross was going on the media and saying, “the amount of devastation that I saw in Yemen in four months equals the devastation that I saw in Syria over four years.” Yemen after four months was like Syria after four years. And that tells you why this country had to be in this situation. Development was never a priority to it.

We have to understand the rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh. He has a huge responsibility in how things turned out, on the humanitarian development level let alone the political level. Today, when we have cholera and famine—the statistics about the humanitarian situation in Yemen are just shocking. And for me, this is just the consequence of the rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh. He was really good at milking the US and UK for funds to his military forces instead of focusing on the development and humanitarian situation.

Today, Yemen is exporting ninety percent of its food and commodities. When, like Sara said, the country is under siege and you can’t get in or out, how can this place be livable anymore? We have to see the role that Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule had to do with where the situation is today, and even the failure of the US and Western countries’ policies of focusing more on the War on Terror instead of on poverty, for example, or corruption.

Growing up, I never thought that terrorism, what the US is speaking about, was a priority for me. Poverty was the terrorism that I knew. I remember growing up eating just yogurt and bread for two months because we didn’t have enough money. Year after year, my mom was running from one court to another, trying to get divorced in a corrupt and misogynistic system. All those problems—the corruption and the poverty—were the main terrorism that we had. Not the image Ali Abdullah Saleh was able to project and sell to Western countries.

SO: Afrah is right. Yemen has been poor for the longest time. And the war now magnifies all these existing problems. When we were on the ground, I saw bridges that were bombed. I saw that they would bomb roads, they would bomb hospitals. There were two Doctors Without Borders hospitals that asked us not to come visit because they had been bombed. There was no discrimination; a lot of infrastructure was bombed. There would be a cement factory, the only source of employment in an area, and it would get cluster bombed. The infrastructure as a whole has been crippled. We saw nurses who told us people are dying on the way to the hospital, because the bridge is bombed or the road is bombed. We saw one girl who came in with severe malnutrition (you see her if you watch the film) and there’s a ton of hospitals in her area, but they don’t feel safe going to any of them, because all of them get bombed, so she had to make a two-day journey to the hospital.

The country was poor before, and right now it’s as if there’s no room and they’re just being squeezed even more with the attacks that are being waged.

AN: I have a question for Sara. I saw the documentary, and it was well done, and great that you’ve done it. But I was wondering how easy was it to go around and film? Were you feeling safe holding the camera and interviewing people? Because as you know, the rule of Houthi in Sana’a—they have had really violent and aggressive crackdowns on journalists. So I wonder how you were received by them.

Yemenis today are unfortunately not asking for democracy and freedom and so on; we just want to end the suffering and for the warring parties to sit down and negotiate. Please stop the bloodshed, the blood craze in Yemen.

SO: That’s a great question, and it’s good that you reminded me of this, because the obvious party blocking journalists is the Saudi-led coalition, but once you’re on the ground it doesn’t get easier at all. The Houthis are not easy. They’re not easy to deal with. We had a minder constantly. I left the hotel once without a minder, and the national security agency was very upset, and they threatened to suspend all our activities. We had somebody who came with us everywhere. At one point we had a camera confiscated because we were taking photographs of trash. One of the producers who was with me had brought a still camera and was taking pictures of trash. Trash is all over Sana’a—that’s partially what’s causing the cholera epidemic.

So the Houthis weren’t very understanding when it came to the importance of just letting us report. I felt like they saw the benefit of having journalists on the ground. They say that they want people to come, they want them to report on the devastation. But they also are very controlling. There’s no value for investigating. There’s a lot of aspects of the war that we couldn’t get into or touch, because of their tight control.

AN: My second question would be what about Ta’izz? Was it easy to go to Ta’izz?

SO: We didn’t go to Ta’izz. We weren’t allowed. There were places that we requested to visit, also, that were just flat-out rejected.

AN: Who rejected them?

SO: The Houthis, because at the end of the day, we were in Sana’a under the Ministry of Information, which is controlled by the Houthis. We had a certain degree of freedom, but beyond that, if you wanted to leave the capital and get through all the checkpoints (and there are many), you needed clearance from the Ministry of Information. So we couldn’t really slip off and go to Ta’izz or Hudaydah like we wanted. We even tried to embed with an NGO so that we could go to Hudaydah, and that was rejected.

We managed to see a lot, despite knowing that it’s a huge place and there’s a lot going on, and it’s specific to each province—I’m very aware of that. But when you’re operating under such tight restrictions you just do your best to go where you can.

It’s really important to remind people that it’s not just the Saudis who are committing violations. But it’s much easier to report on airstrikes than it is to report on violations from within. When you don’t have journalists allowed to even enter the country, and when you are trying to piece together evidence of what they’re doing—I mean, an airstrike is quite visible, right? You bomb a funeral hall, you kill 150 people, people will write about it. But arresting a social media activist or an online activist that only people who follow Yemen closely really know about—it’s difficult to get attention.

I’m not defending that. I’m just explaining why people focus on the Saudi crimes over the Houthi crimes. It’s very hard to pin down what they’re doing. Even when we talk about Iran being there—that’s the reason why this entire thing is happening; the coalition has invested millions and millions to fight Iran in Yemen. It’s very hard to concretely see where that is. Especially when you don’t have people reporting on the ground and being able to get in and get out and get information.

M: Historically, from other conflicts in the region and from other conflicts around the world, you can always pinpoint the main players in this game by trying to put your finger on the weapons that are being used. Where does Saudia Arabia get its weapons from? Saudi Arabia obviously doesn’t manufacture its weapons. And where do the Houthis get their weapons from? You always have that indicator. We know that the Houthis could not continue fighting if they did not have well-supplied logistics, and same with the Saudis.

How do the international players come in, in enabling both sides to exacerbate this humanitarian problem?

SO: In terms of the Saudis and the Saudi-led coalition: when we were on the ground there was a massive rally organized—I don’t know if it was orchestrated, but it took place—to protest president Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia, where they were giving them weapons. That’s the most obvious answer as to where Saudi Arabia is getting a lot of its weapons from. It’s getting them from the United States. For a while, the United States was even supplying them with cluster bombs, that are illegal internationally, and they were using them. It took a while for them to admit it, but finally they did.

The Saudis were getting their weapons under Obama, too. When Obama was trying to get the Iran deal going, part of appeasing the Saudis (who were very upset) was to close one eye over their campaign in Yemen. The US obviously isn’t bombing Yemen, but it gives Saudi Arabia logistical support, mid-air refueling, and it supplies them with the weapons that they use.

In terms of the Houthi side, to be honest, I can’t really speak to where their weapons are coming from. The country is flooded with arms, also, and I’m sure Afrah can talk more about this, but in terms of Iran: there’s a group called Conflict Arms Research Group, funded by the EU, and they’ve been recruited by the Emiratis to collect the weapons that are seized from the Houthis (whether it’s drones or the little rockets that they sometimes fire across to the other side, etc.). They’ve noticed that the technology they are using with the drones matches exactly the drone technology of Iran. So Iran definitely helps them technologically, but it doesn’t supply arms in the amounts that the Saudis are getting from the United States.

M: Obviously, because they have to do it undercover, and it’s a lot harder to bring them into the country. But even if Yemen had an armed state, and everyone had weapons, there’s a difference between being an armed state and having enough ammunition to sustain a war. If I had a few boxes of ammunition in my house, and my neighbor had a few boxes in his house, within the first few months of the war those have been used up. So there is a supply line of weapons coming in.

AN: I have two main points. One, we have to understand that Yemen’s history is very bloody, full of hard-fought conflicts. Starting from the ’62 revolution, where Egyptians had a huge role in trying to oust the imam, there was the first socialist political party in the Arabian peninsula, founded in the south of Yemen, and they had an armed wing as well. All of those aspects contributed to making Yemen, per capita, the second-most armed country after the US, actually.

But we have to understand the Houthis: they come from fighting. They have this fighting heritage, and they have been fighting Ali Adullah Saleh for six years. To be fighting is not new for them. If there is anyone who is well experienced and skilled in fighting, it’s going to be Houthis. So it’s very important to look at the fighting culture in Yemen, and try to understand how it has a role today, and how these components are still armed.

We didn’t go to Yemen to make the documentary we made. But we felt like sitting on all this material that shows the humanitarian crisis is a crime. We could not just wait for our larger film about Saudi and Iran to come out next year.

As for Ali Abdullah Saleh: when the War on Terror began, he was one of the first allies to the Bush Administration at that time. He milked millions of dollars from the US administration, and they were sending him a lot of weapons in the name of fighting terrorism. Most of those weaponry storages are being bombed by the Saudi-led coalition today; he used these weapons to empower the military forces of the Houthis as well. These weapons are still being used today.

Lastly, one of the most under-reported aspects in the ongoing Yemen war is the weapon trades going on and the war business when it comes to the weapons in this war. For instance (it could be a wild idea, and I don’t have any evidence) my question is whether the legitimate government today is taking some of the weapons from the Saudis and smuggling them to the Houthis in order to continue the conflict. Are there internal or infiltrated groups between the Houthis and the legitimate government trying to profit from the war?

This stuff is really hard to report on, because there are definitely a lot of things going on under the table. This also includes questioning the Iranians’ role in supplying weaponry for the Houthis. Every journalist should try to dig into this story. But who is willing to risk their life? It’s definitely not going to be an easy story to cover.

SO: If they can get in first, then we can talk about if they can risk their lives.

Another thing we didn’t mention about how they’re sustaining the war is the number of people they’re recruiting, particularly children. We were on our way back from Sa’dah, and we were driving to Sana’a, and we stopped and saw this graduation of little cadets that are going to go and fight with the Houthis. It was all from one tribe, so the men of the tribe were there, and there was a speaker, and they had all the kids in uniform marching, and telling them how they are about to go and join the front line to fight against the Saudi coalition.

We were filming there, and I was looking at the people graduating, and they all looked like they were in their teens. It was quite obvious. There are a lot of people on the checkpoints who are young. When we spoke to our minder about this, he said there are many young kids who are on the front line being used to fight. So that helps sustain the war. There are kids either choosing to fight or being forced into fighting.

And bombing does convince people on the ground that they are at war, and that they need to fight. The bombing campaign helps sustain the fighting. I felt like Yemenis understood that no one was really a good guy. Really. When I talked to people on the ground, they understood that everyone is squeezing them. But at the end of the day, the bombing campaign pushes them towards wanting to fight the Saudis.

LM: Exactly, and this is the same thing that happened in Syria. You cannot expect people not to be willing to fight if they are seeing their whole families being bombed in front of them.

I asked people to post questions, and I think we managed to answer all of them, but just one question left for you: Is there anything you would like non-Yemeni activists to do?

AN: It’s a question of which side of history you want to be on. Anyone who’s listening to this interview and is really interested in trying to help Yemenis: each one has his or her role to speak out. Writing on social media; writing to your politician and asking what role they have in the tragedy going on in Yemen; going to demonstrations and speaking out, and trying to raise global awareness about what’s going on in Yemen. Everyone can do something.

Definitely one person cannot do everything, but everyone can do something that could raise awareness and help Western countries and the Yemeni authorities understand that we’ve had enough. We’ve lost so many lives, and it’s time to sit down at the table and negotiate and find a deal. Yemenis today are unfortunately not asking for democracy and freedom and so on; we just want to end the suffering and for the warring parties to sit down and negotiate.

Please stop the bloodshed, the blood craze in Yemen, and then we can inquire, negotiate, and so on. Everyone can do at least one thing that could help Yemenis, definitely. And donations of course.

LM: Who do you recommend to follow on Yemen?

AN: It’s very frustrating, even for me, to follow what’s going on in Yemen. It’s very important to stress the fact that many of my colleagues in Yemen are in jail, imprisoned by the Houthis, and they have been detained since the beginning of the war—almost three years now. They were imprisoned without trial. Right now there is one Yemeni journalist, for the first time in Yemen’s history, being prosecuted, and he is getting the death sentence. Journalists have suffered a lot of hardship from this war.

It’s very difficult for me to recommend anyone.

SO: I agree. It’s very difficult to recommend anyone. I used to follow Hisham al-Omeisy, who just got arrested a few weeks ago, and we don’t know what his fate is. It’s not that there’s a lack of intellectual and honest and smart Yemenis who do good work in Yemen. It’s more that for people on the ground right now reporting, it’s really hard to find someone who will talk to you, or who you can follow.

I hate to say this, but right now I’m following people who are outside.

AN: In solidarity with Irrelevant Arabs, I want to mention that I am also inspired to start something because of this lack of finding a reference for journalism. I’m starting an online magazine called Sana’a Review, and this is going to be one of the topics that we want to discuss in the magazine. We’re trying to open more space for journalists inside the country who want to reach out to other journalists like Sara and others, and trying to bridge and have an open channel for people who want to know more about Yemen and offer a more specific place other than random Twitter accounts and Facebook accounts. Hopefully that will get a bit of support and love.

SO: Can I say something about Iran and Saudi Arabia before we finish? We went into Yemen because we were doing a documentary about the Saudi-Iran rivalry. That was the main reason we went. We collected a lot of stuff, but when we came out it was very clear to us that despite the Saudi-Iran rivalry, at its core, what is happening is: people are suffering.

We didn’t go to Yemen to make the documentary we made. But we felt like sitting on all this material that shows the humanitarian crisis is a crime. We could not just wait for our larger film about Saudi and Iran to come out next year.

The reason I’m saying this is: yes, there is a Saudi-Iranian struggle going on, but Yemenis—no matter how simple they might be in the village or whatever, or if somebody is really sophisticated, whoever it is—when we talked to people who were cluster bombed or received airstrikes, no matter who it was, they didn’t know why they were targeted, most of the time, but they knew where the weapons were coming from. They would tell us that this was a US-made rocket, or a US-made cluster bomb, or a British one.

It’s important to say that people know who is supplying the weapons, and this needs to be addressed very quickly, especially in places like the US and the UK where you can go and lobby and protest and write petitions and harass your representatives on your country’s role in the war.

LM: I don’t want to get deported, but I agree this is what activists in this country should do. Just raise your voice against what’s going on in Yemen.

I learned so much. Afrah, thank you so much. I really appreciate your time.

M: Yes, Afrah, thank you so much, and Sara, thank you so much for being here.

AN: Thank you for having me.

SO: Thank you guys.

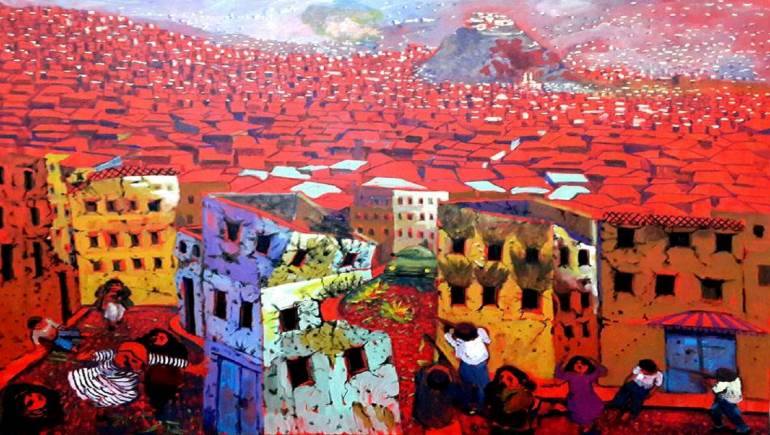

All images: Afrah Nasser (Facebook) or Amr Gamal (Facebook).