Ice Cream, Concrete, and Squats

Gentrification and resistance in Zurich

by Miriam Damari for ajour magazin (Switzerland)

17 November 2017 (original post in German)

A local alliance of activist groups in Zurich has been drawing attention to the “many faces of gentrification” with a poster campaign, and has called for demonstrations. Although concerns are being focused primarily on central city neighborhoods, a glance at the north side periphery of Zurich reveals similarly rapacious speculative development and displacement through the artificial appreciation of real estate values. Where there used to be factories, the city wants to build up—high up—and the skyline is increasingly being dominated by glass and concrete office towers. With far-reaching consequences for the former workers’ quarter Oerlikon and its residents.

Zurich-Oerlikon: Buffeted by the rattle of jackhammers, the Andreas Tower looms high above the train tracks. Though it is not yet complete, it already exudes all the discreet charm of business-casual and champagne flutes. It is no wonder that this grand trophy of neoliberal development excess was created by the same architects who blessed us with the Prime Tower.

The Andreas Tower is a project of SBB-Immobilien [the real estate branch of the Swiss railway conglomerate]. SBB-Immobilien operates under a mandate to generate profit—it accomplishes this, however, on city land and with the help of the city in removing regulatory hurdles to new construction. For this it has been criticized even in the architectural journal Hochparterre: SBB is a state operation that, in the case of the Andreas Tower as well as many others, profits off the public but gives nothing in return (e.g. by including public, low-income, or community housing in its development plans). Besides its 20,000 square meters of office space, the SBB’s Andreas Tower will otherwise provide units only for retail and food service.

In its promotional materials, descriptions of the Andreas Tower read like a neoliberal dream. It will be “vibrant, flexible, and easy to get to.” One passerby pushing a stroller sees it differently: “One thing’s for sure: there will be more traffic and Oerlikon will be more crowded. Whether and how the neighborhood will be negatively affected, I can’t say, but it is definitely conceivable. It presumably won’t be child-friendly either way.”

Whether office towers are actually more lucrative for SBB-Immobilien than apartment towers is unclear. But statistics show that the equivalent of nine Andreas Towers’ worth of office space is already standing vacant in Zurich.

A farm town’s meteoric rise

Until the turn of the millennium, Oerlikon was a place people landed when they were forced out of the center city; now these same people are being pushed even further to the margins by the march of progress.

But let’s go back even further: Oerlikon developed rapidly during the twentieth century, transforming from a small town into a central hub on Zurich’s north side in a relatively short time. In its small-town days of the mid-nineteenth century, Oerlikon was already caught in the throes of industrialization. Rail lines and a small train station were constructed, and north of them an industrial zone began to form. This started with the Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (MFO), which later became Oerlikon Bührle, a factory which among other things produced arms for Nazi Germany. This industrial development drew workers to Oerlikon, and the community on the city side of the tracks began to urbanize. From then on Oerlikon experienced a steep ascendance.

As in so many other places, though, towards the latter part of the twentieth century Oerlikon’s manufacturing base began getting outsourced. Factories closed, leaving behind a post-industrial wasteland—in response to which plans were prepared for revitalization: North Oerlikon (Oerlikon-Nord) would become New Oerlikon (Neu-Oerlikon). Implementation began in 1995. Shiny new neighborhoods were pounded out, popping up seemingly out of nowhere. Having had no time to grow historically, they now produce a feeling of emptiness.

Today Oerlikon is supposed to become the independent commercial center of the entire Glatt river valley. The newly renovated and expanded train station as well as prestige projects like the Andreas Tower (and the Franklin Tower, still in its planning stages) serve as marquees for this endeavor.

What’s up with this capitalist city planning?

Urban space is not designed according to its possible uses or benefits for residents; this fundamental deficiency characterizes capitalist city planning. Instead, the central criterion is the financial gain that beckons from any proposed redevelopment. Developments are driven by surplus capital flowing out of other economic sectors and into construction.

Gentrification is the term often used for the combination of development and displacement. It describes the rearrangement of social structures as a consequence of redeveloping physical structures. People of low- and middle incomes are replaced by people of higher incomes. The character of the affected neighborhood is thus fundamentally altered.

This process can be observed in Oerlikon. In particular, Schaffhauserstrasse in Alt-Oerlikon [Old Oerlikon, the workers’ quarter south of the tracks discussed above] is a good example of what the first phase of gentrification can look like. In an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Schaffhauserstrasse is described as a colorful mishmash of a street—one displaying a “lived anti-gentrification.” This observation is based on the diversity of the the street’s residents and shops. Of course, there is something phony about this liberal song of praise. Zurich’s bourgeois paper of record is indeed accomplishing the first step of gentrification right there: the growing attractiveness of the street will simply serve to draw in more deep-pocketed investors, renters, and consumers.

An earlier version of this in the area was the Edison-Franklin-Querstrasse Triangle project, which was realized by a private investor who between 2008 and 2012 had the buildings on this three-sided block torn down, put new ones in their places, and did a full remodel on others. Because of the increased rents in the new and rehabbed buildings, a whole new population arrived in the center of Old Oerlikon.

There weren’t any residential buildings in the place where today the Andreas Tower is reaching skyward; nonetheless, it will alter the surrounding neighborhoods through the consumerism it draws. On the one hand, more than a few high-earners will want to move to the vicinity of their workplace, increasing demand for upscale housing. On the other hand, shops, restaurants, and other service sector businesses in the surrounding area will increasingly cater to this new clientele. A similar process can be observed around Hardbrücke: since the the Prime Tower was erected in this former industrial zone [in central Zurich], the neighborhood has become a citadel for bankers and office administrators.

The many faces of gentrification

Oerlikon is only one example among many. More notorious for gentrification in Zurich are of course the central Fourth and Fifth Districts along [the former red-light thoroughfare] Langstrasse. Especially notable is the Europaallee commercial development—again a project of SBB-Immobilien—which now cuts a concrete swathe directly into Langstrasse from Zurich’s main train station.

Langstrasse has been undergoing gradual transformation for decades. It was originally the central artery of the distinctly proletarian Fourth and Fifth; more recently it has become an exclusive commercial strip in its own right. Because of the most recent real estate value and other price hikes, Langstrasse is now too expensive even for the previous waves of hip newcomers.

On the other side of the tracks from Langstrasse is Neugasse, where another development megaproject is planned—again by SBB-Immobilien. Residents of the Neugasse neighborhood have launched a campaign demanding that the entire complex, which is set to include both residential and commercial space, be not-for-profit and serve the public good.

Of course, gentrification is not something that only happens where glass palaces and megamalls are built. There are also more subtle versions. Individual buildings in the districts abutting Langstrasse are being renovated or converted. Rents go up, making it impossible for the proletarian and migrant populations of the neighborhood to remain. In addition to that, the cost of living in the neighborhood goes up more generally; boutiques and chain restaurants abound. Lilly’s, for example, is a chain restaurant that just moved into the previously humble Lochergut neighborhood [in the Fourth District] and has aided in prompting an across-the-board increase in consumer prices in the area.

But it’s not only that; the demands of well-heeled newcomers for more spacious dwellings and workplaces also lead to the phenomenon of fewer people living within a given (or even a larger) space. We can no longer speak of “density” in the inner city.

Multiple vectors of resistance

Currently there is a poster campaign that points up these multiple aspects of gentrification and attempts to propose multiple responses. Under the title Aufwertung hat viele Gesichter [Gentrification Has Many Faces], specific aspects are called out depending on the location or property where the poster is placed. On a standard-size sheet of office paper, framed by several pairs of ears, the “face of gentrification” in question is described in detail.

In Wiedikon [another central city neighborhood, in the Third District] the process has been a long one: it began with Idaplatz, where, in the expectation that real estate values would rise with the traffic-calming project on Weststrasse, investment started pouring in. The process culminated in the lines of asylum-seekers waiting at the legal aid office being replaced with lines for gourmet ice cream.

“After the International Congress Against Capitalist Urban Development, in May of this year, we asked ourselves how the issue of urban development could be reclaimed and what forms direct action could take on the matter,” explained Maurice, a participant in the poster campaign. “The posters are one attempt at that.” It’s only a start, though: a demonstration was also being planned. “We think that gentrification is advancing really fast right now, so it’s time to go with a more dynamic kind of action. Also, there hasn’t been a demonstration on the issue of gentrification in quite a while.”

This fall people also took to the streets against gentrification and displacement and for self-organized autonomous spaces in cities other than Zurich. In Geneva a demonstration about 3,000 strong took place at the beginning of October. Its focus was on the collective housing initiative Malagnou, which is under threat of eviction because of aggressive privatization efforts in the city. The demands of the CUAE, the students’ union at the University of Geneva, were also prominent: they are calling for better living conditions for young people.

And at the end of October in Bern, on the occasion of the 30-year anniversary of the autonomous cultural center Reitschule, a large demonstration with the title “Thirty Years Is Not Enough” took place. The Reitschule is a practical example of what it means to reclaim space in the city and remake it according to one’s own ideas and conceptions of a society worth living in.

Personalization doesn’t do the issue justice

Gentrification is a broadly-discussed issue in Zurich, and many different groups are grappling with it—among them those being compelled by outside forces to do so. Bourgeois media such as the Tagesanzeiger or the NZZ report on it fairly regularly, even if the latter mostly does so in the form of refutations. A not totally disparaging article in advance of the Zurich demonstration even appeared in the free daily commuter rag 20 Minuten.

The forms of resistance to gentrification are as diverse as the forms taken by gentrification itself. Our task now is to connect our various struggles and start to think and work together. In order to do so, we cannot simply name and blame those individuals among us guilty of gentrification. The structures that make it possible for the few to profit at the expense of the many must also be named, denounced, and fought—because gentrification is class war from above which must be answered with struggle from below. This will require accessible projects that can establish a broad and militant praxis.

Points of entry and connection exist already. Many social issues find solid purchase within the struggle for affordable and public housing. The mentioned megaprojects like Neugasse or the Edison-Franklin-Questrasse Triangle, as well as big players like SBB, offer more than enough attack surface to direct our energies upon—on the one hand because their outsize dimensions mean they are already topics of political debate, and on the other because the consequences of such projects are never confined to the cubic meters they inhabit. As we can see in Oerlikon, the neighborhoods that abut these projects and the “downstream” neighborhoods to which people are displaced—as well as the broader periphery writ large—are all also transformed.

Therefore these struggles must take place in all these affected neighborhoods, and must regard the interconnection and self-organization of their residents as a central goal. Then even when these projects can’t be completely prevented, alternative structures and cultures of resistance still emerge.

Translated by Antidote

All images via ajour magazin

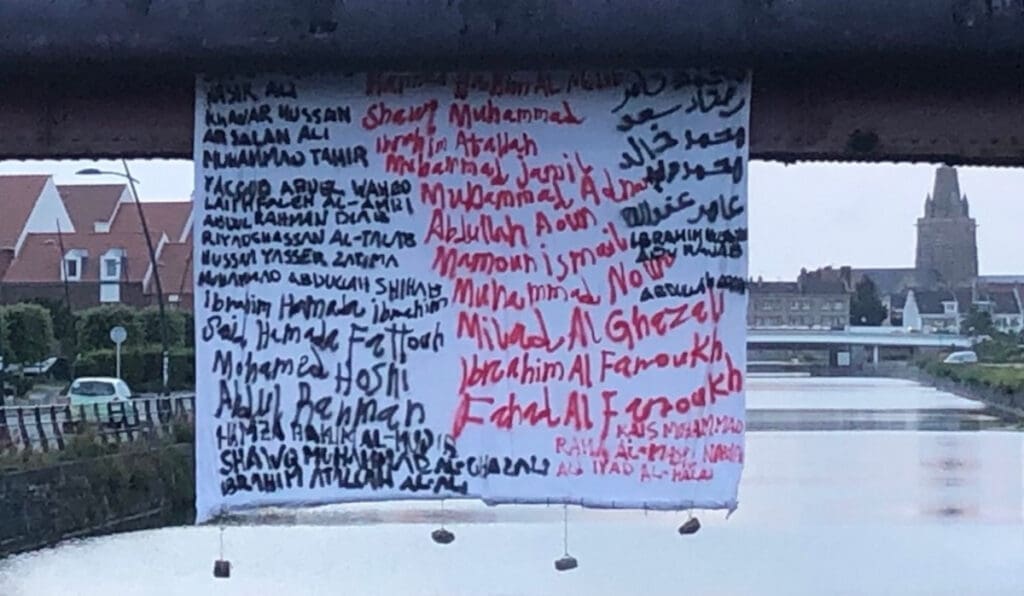

Here’s a selection of the photos ajour posted from this fall’s anti-gentrification demo in Zurich mentioned in this article (18 November 2017):