Transcribed from the 16 December 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the entire interview:

The black radical tradition contains forms of oppositional thought produced outside the matrix of the West. In other words, there wasn’t a direct dialectic between bourgeois democracies and the experiences of African people. It’s a critique of bourgeois democracy coming from outside of that space.

Chuck Mertz: Cedric Robinson’s seminal work Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition illustrates why Robinson is a guiding voice in black radical thinking. So what is black radical thought? Where did it come from and how did it get that way? Here to guide us through the journey of black radical thinking—and Cedric Robinson’s—historian Robin D.G. Kelley wrote the essay “Winston Whiteside and the Politics of the Possible” in the collection Futures of Black Radicalism, which we have been featuring on our show and is edited by past guests Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Robin.

Robin D.G. Kelley: Great to be with you, Chuck.

CM: Thanks for being on our show.

For those who have not heard our earlier conversations on Gaye and Alex’s book and may not be as familiar with Cedric Robinson as they are, say, with martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X, why was Cedric Robinson’s writing and work so important—especially today, given our political environment and movements such as Black Lives Matter?

RK: He was ahead of his time not just in terms of analyzing the relationship between racism and capitalism—what he termed racial capitalism—but in making an argument about what he called the black radical tradition, that is, a way of understanding opposition and resistance that cannot be reduced to a universal class analysis or even the idea that somehow all forms of opposition can be structured within Western consciousness. In other words, so much of what was understood to be resistance to capital always took the form of the proletariat, the working class as universal subjects. But Cedric said Africans were taken out of a particular context in which they had a notion of being—a notion of ontology, a notion of philosophy, an understanding of culture—that was radically different from the West. That culture, that ontology, that sense of being, that sense of the world was what shaped their forms of resistance.

In other words it wasn’t like they were simply products of slavery. They can never become slaves. They were ultimately Africans. And for Africans, what mattered more than, say, revenge, for example, was finding ways to be one, to be together in their opposition, and to build a culture based on that past. That’s part of what’s in his massive text Black Marxism.

I should say another thing about the book: it was written in three parts, and the first part is a critique of Western Marxism (without necessarily throwing it out) that looks at the way race and nationalism shaped not just Marx and Engels but the way that the critique of capitalism had emerged. Then he talks about the long history of the black radical tradition going back before slavery, and then he talks about three intellectuals—W.E.B. DuBois, C.L.R. James, and Richard Wright—and how they were not just products of the black radical tradition but had to discover it in their own research and scholarship and activism.

CM: And we’ll get to that discovery in just a second. So Futures of Black Radicalism’s cover design is an homage to Cedric Robinson’s seminal work, Black Marxism. Why is black Marxism so important? As Dr. Nikhil Singh writes in Futures of Black Radicalism, “Marxism falls short when it comes to black radical thought, as it is Eurocentric.” So why is black Marxism so important, and how is black Marxism different from Marxism?

RK: Cedric wasn’t making a case for some version of “black” Marxism—that’s how it’s often read: “These are the black Marxists.” When people talk about the black radical tradition, they want to name off black Marxists. But that’s not the point that Cedric was making. Cedric was actually putting those two words together not so much as a compound but as a confrontation, a confrontation between the black radical tradition and Western Marxism. What he argues is that the intellectuals who discovered the black radical tradition came to it through Marxism. Marxism was their passageway to find it. And when they found it, what they found were all these unnamed people in revolt.

During reconstruction after the end of the civil war, for example, there was a particular vision of freedom and democracy that DuBois discovered. There was the Haitian revolution, where Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacque Dessalines were important figures. But what C.L.R. James wrestled with was that all those masses of people had no conception of, say, Hegel or Marx or Feuerbach, and instead were seeing a pathway to liberation based on a way of thinking about people—each other—as a community shaped by an African past.

So it’s not that Cedric is rejecting Marxism. He’s saying that dialectical thinking was the way to discover the black radical tradition. But that’s not the same thing as saying there is a Black Marxist. It’s important because we—on the left, at least—end up having debates among varieties of Marxism, or varieties of Marxism versus varieties of anarchism, or varieties of Marxism versus varieties of social democracy. But Cedric is saying that once you bring the black radical tradition in there (and you can say the same thing about indigenous thought), these are forms of oppositional thought produced outside of the matrix of the West. In other words, there wasn’t a direct dialectic between bourgeois democracies and the experiences of African people. It’s a critique of bourgeois democracy coming from outside of that space. He’s saying we need to pay homage to that.

There was a talk Cedric gave in 2013 where he made a case for the religion of enslaved people as an ideological and political foundation for black radicalism. He rejects the idea that we can understand the enslaved through an analysis or framework of social death. No, these are people who actually believe, who felt that faith was something more than just the opiate of the people. Rather, it was the belief that they could produce a good society, a utopia—even if they don’t live to see it, they have to live that life. He’s saying that these were people who we thought of as commodities, and they never allowed themselves to be commodities. In fact, they could invent and manufacture, conspire and organize, way beyond the possibilities. That’s what he saw in the enslaved.

That’s a very important argument to make now, because we’re struggling with this idea (coming from Afro-pessimists in particular) that the enslaved basically have no history, that they are completely reduced to factors of production, that they are fungible, and that we have to pay attention to social death rather than see them as agents of history—if not the most important agents in the making of opposition to the Western world as we know it.

When capitalism emerges, it emerges already imbued with racial hierarchy. It was already racial. Capitalism didn’t have to use race as a way to make itself work. It was already there as part of the logic.

CM: You mentioned racial capitalism earlier. How do we view the world differently if we see racial capitalism? We had the editor Cindy Milstein on the show; she has a new book out about the radicalism of mourning, and she talked about how when she puts on her anarchist glasses, she can see all the disparities of class. And we talked to Kate Manne about misogyny, and she talked about how if you put on your misogyny glasses, you can start seeing the patriarchy around you.

What do we see when we put on our racial capitalism glasses? And is Black Lives Matter a revolution against racial capitalism?

RK: The glasses metaphor bothers me a little bit, but I know what you’re saying. I resist the glasses metaphor only because racial capitalism is not one set of glasses—nor is misogyny one set of glasses. We should be able to see all these things together. In fact, that’s been the problem.

The term racial capitalism is another misunderstood term. It has a very long history that precedes Cedric’s work, I should say. In fact, the term was used in South Africa to understand apartheid as a modern capitalist system that organized capital through a racial regime. That was before Cedric wrote Black Marxism; people in South Africa were talking about this in 1970.

When Cedric was using it, he meant something very specific. He was talking about the genesis of capitalism itself. This is a very important part of this issue about the glasses. He didn’t want to get into the debate about what comes first, the chicken or the egg. He argues that racialism (that is, racial hierarchy and the production of difference within Europe itself) had preceded the development of capitalism—which he also dates way earlier. He’s going back to the twelfth century. He’s going back to plantation societies in thirteenth century Cyprus. He comes from a world-system-theory understanding of the world. He’s saying racialism already existed. It may not have taken the form of anti-African or anti-blackness. But it certainly took the form of anti-Semitism. It took the form of anti-Slavism. It took the form of constructions of difference within this category that we later called white.

He mentions the fact that there were Britons who were enslaved in the fourteenth century, and that the Irish, in fact, were among the most racialized group under English colonialism. Then he says when capitalism emerges, it emerges already imbued with racial hierarchy. It was already racial. Capitalism didn’t have to use race as a way to make itself work. It was already there as part of the logic.

He also argued that capitalism was not inevitable—that in fact there were all these alternatives to responding to economic and political crises, and capitalism was just one. Socialism was another one. And this is where he rejects some of the claims made by Marxists. He doesn’t completely reject them, but socialism had its origins in the old Baptists, the Christian Socialists from way back in the early part of the millennium, and that it was just another way to try to reorganize society given the crisis of feudalism.

He says that none of this stuff is inevitable. What we do know is that race and capitalism are merged together, so as it emerges into the modern era of the nineteenth century of liberalism, you cannot separate race from capitalism. By extension, you also can’t separate patriarchy from capitalism. You can’t separate forms of what becomes white supremacy, notions of Eurocentrism. Eurocentrism was not something that was a trick on the part of capitalists to justify its exploitation of the world. It was so built-in to the ideology that it just became part of the common sense, the common logic of this structure.

What are the implications of this? The implications are that in places like South Africa or the United States, you cannot dismantle capitalism without dismantling racism. You can’t choose what’s going to be more important. These things go together. Same thing for patriarchy. So if we take our glasses off and come together and see the whole, see the world system in motion, then we see these things as so inseparable and so mutually constitutive that we have to build movements that take them all on and realize that, as complicated as it might look, we have no choice.

CM: You quote Robinson saying, “Christian faith trained me to be able to believe in and to anticipate something coming into being that was not in being. That’s called by the Greek word utopia, which means the good society. It also means no such place. That gave me a framework for looking at what others before me had imagined was possible in their lifetime, and that’s why it was so important for me to look at the notion of radicalism from the vantage point of slaves.”

There are those, Robin, who see religion as something “ridiculous.” They argue religion does no good, or has outlived its usefulness. How important is the Christian faith when it comes to Robinson’s black radicalism?

RK: Cedric would not say it’s rooted in Christian faith per se. He would say Christianity has also been the oppressor, both in terms of its state form and in terms of its form on the plantation and other structures of domination. It has been the ideological baton used to beat people down. He recognized that very clearly. But he also recognizes that when we talk about spirituality and religion, its roots are still pre-Christian and pre-Islam.

I should back up just to give you some background on Cedric. Cedric got his PhD from Stanford, and when he was there he took courses in African politics. He did his undergraduate degree in anthropology at UC Berkeley, and he took courses in African anthropology. In the early 1960s he went to what was then Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) with Operation Crossroads, and lived in Zimbabwe with a group of young people, built schools and that sort of thing, and in the summer of ’62 witnessed the attack on the liberation movement and the shift to rightwing rule in that country, which was already independent (it had been a British colony).

There’s a lot of work out there that was forced to be radical by the circumstances. In the 1930s the questions were: What is the future of the colonies? What is the future of the West in the face of fascism? How do we build movements that could overthrow this racial structure? These kinds of crises produce new radical works.

So he was always immersed in trying to understand African culture in time and space. When he talks about the Christian faith, he’s talking about a particular way of experiencing and articulating Christian faith through African and African-American experience. And it’s the same with Islam. He does talk about Islam as one of the root forms of rebellion, in Part Two of Black Marxism. He also talks about Islam as one of the structures through which the trans-Saharan slave trade took place.

He never took the position that there’s something inherently radical about religion, or that there’s something inherently reactionary; it has to be understood in the context of the dispossessed and the marginalized who embrace these forms of thinking, and that they transform them. That’s the most important part of it.

Even though Cedric called himself an atheist—or at least at some point he did—he grew up in a household where his grandparents became Seven Day Adventists (though they had been Christians before that; Baptists). He went to church. He understood it. He recognized the power of the experience. But for him, it still was a historical and ontological experience, as opposed to something inherently radical.

CM: You write, “Cedric Robinson always wrote about black radical futures, but history was his pathway for comprehending what others imagined was possible in their lifetime. He consistently turned to the past to understand the black radical tradition and its capacity to envision a world beyond the possibilities.”

As academics learn more and more about African-American history, are they learning more about black radicalism? Is the study of black history the study of black radicalism? And to what degree does the study of black history radicalize the student of black history?

RK: I’ve been grading papers all night. My cynical self says, no it doesn’t. But Cedric makes the case that much of what we think of as modern black history (and when I say black history, I don’t just mean North America, but the black world) is grounded in radical critique of what was then the current arrangement. That’s why Cedric ends up writing about DuBois and black Reconstruction in 1935, and C.L.R. James in 1913—as in: this is not new. But it’s not only that it’s not new: more than anything else, the study of the history of black people and black movements is always framed by the crisis and the possibilities of the moment.

In the 1930s, there was a whole slew of work in the name of what we call “black history” that was quite radical, far more radical than much of the work that we saw decades later. Beside DeBois’s and James’s great work, there is a whole slew of scholarship on black working class movements, George Padmore and others. There was work on slavery and anti-slavery being written in this period of time, in the 1920s and ’30s. There’s a lot of work out there that was forced to be radical by the circumstances. In the 1930s the questions were: What is the future of the colonies? What is the future of the West in the face of fascism? How do we build movements that could overthrow this racial structure?

These kinds of crises produce new radical works—or at least they produce the imperative to do the work. I don’t want to say they produce the work; it’s these brilliant scholars who do that, and the movements that force them to do that.

Having said that, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the enterprise that we call black history is always a radical enterprise. Institutionalization at various universities can produce quite the opposite: very conservative, reactionary conclusions. They can be deeply nationalist and closed off to other possibilities, or deeply liberal in that they are striving to prove black citizenship or rights of citizenship, and therefore the right to be like everyone else without changing the current arrangements. That scholarship exists as well, and it has existed throughout. It ebbs and flows.

We could talk about writings by Martin Delany in the nineteenth century, or we could talk about Anna Julia Cooper. Most people think of her as a brilliant feminist thinker. She’s a great historian who wrote about slavery in the Francophone world. That work is always there. I’m always compelling my students to go back and read that work, rather than always jumping to the latest, hottest thing. I think the book Futures of Black Radicalism will also do the same: force us to go back and try to read what Cedric was reading, try to read what really shaped a generation of thinkers.

CM: You write, “Cedric revealed that the source of his own conception of the possible was not some seminal text or archival revelation, but his West Oakland upbringing, his Alabama roots, his family, and the community that nurtured him. While Cedric was reluctant to dwell on the autobiographical, he never hid the enormous respect and admiration he held for his maternal grandfather, Winston Whiteside, whom he often cited as a formative intellectual influence.”

Is black radicalism, then, more grounded not in a seminal text or archival revelation, but personal experience and the impact or influence of previous generations on your life? How much does that take black radicalism out of the theoretical and into the practical and pragmatic? In conversations I’ve had with those on black radical thought—whether its contributors to this book or contributors to Jackson Rising, or Herb Boyd’s history of Detroit and black self-determination—black radicalism has already implemented many of the radical ideas that white radicals are only now beginning to discuss in theoretical terms.

So how much do you think this lack of reliance on seminal works and archival revelations, and actually looking to and learning from previous generations brings the theoretical into the practical more in black radicalism than in what we might call white radicalism?

RK: I think that for black radicalism, there was never a separation between the theoretical and the practical. They’re inseparable. These so-called “ordinary” (but, I argue, extraordinary) people were able to envision a different future at their lowest point—meaning to be owned and sold, to have families broken, to live under the lash. Under those circumstances, you had to imagine something beyond what you have. You could not expect that every day will be the same. That’s the work of theory: theorizing exactly how the society works and what its weaknesses are and how you can unravel it to build something new.

Sometimes the very people who claim the mantel of radicalism could be slowing us down. One of the lessons that Cedric gave us was that even those who claim the mantel of Marxism can also have a very limited vision. And the people who may have no relationship at all to Marxism may actually have a vision that we need.

That’s how people came out of the condition of slavery with a vision of what to do: land, churches, schools, the franchise. Forms of community, forms of sociality. They knew that stuff. Theory made that possible. And that theory was possible not just because of practical everyday experience but this huge conceptual leap beyond the everyday to something else. To me they are inseparable.

When it comes to the story of Winston Whiteside, he is the perfect example to me, the perfect corollary to DuBois discovering all these people in South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi, who don’t have names that we know in the archive, but who were actually building democracy on the ground. He learned about American democracy by looking at how they moved and what they did and the choices they made.

I would argue that much of Cedric Robinson’s understanding of politics, of democracy, of social movements, what moved people—his whole conception of the black radical tradition is shaped by living with his grandparents and seeing their role in the community that surrounded him. To hear stories of how his grandfather made a choice to avenge his wife and flee Mobile, Alabama to go to Oakland—these stories had a huge impact on Cedric. Not just because they are stories of courage and heroism, but because they’re stories of a family that’s not going to accept what Alabama gave them. No, we’re going to carve out a different future.

Let me just give you some background here. When I first saw the Wikipedia entry for Cedric, which I’d never looked at before even though I’ve written so much about him, I noticed that it mentioned Winston Whiteside as one of his influences. There was also an interview where he said the same thing. But the section for Winston was just blank; there was no link. I kind of knew that this was his grandfather, but I didn’t understand who he was. So I just went on a binge—that’s why you noticed the archival research. I went to the source. I spent three weeks doing nothing but researching his grandfather just after he died.

If you don’t mind me getting a little personal here, it was a catharsis. Because losing Cedric was huge to me. He was the most important mentor I’ve ever had in my life. I wept. I didn’t know what to do. I felt lost, and I felt lost because in my own shyness I never really asked Cedric all the questions I wanted to ask. I never really engaged him, I always kept my distance, because that’s how I am, that’s my personality.

Studying his grandfather was my way of understanding him. That was my catharsis. And I’m really happy with this discovery, because we begin to see the long tradition going back to Benjamin Whiteside, and Clara, and this whole tradition that led us to Cedric Robinson—something that he never disavowed, something he always embraced. That’s not something we see in academia a lot.

That’s why Cedric could have understood better than anyone what’s happening in Jackson with Jackson Rising and Cooperation Jackson; he would have understood Herb Boyd’s brilliant book about Detroit: he understood that the people make history. And not only do they make history but they theorize history. They theorize a possibility, and that’s the only way they can move.

CM: Robin, I’ve got one last question for you, and as we do with all of our guests, it’s the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

How much can studying black history radicalize…white people?

RK: I have two answers. One is that it depends on what you study. In the end, it’s not simply a matter of studying the experience of black people, but studying radical critiques of race and capitalism that puts a lot of emphasis on the ways in which subjugated people move. It’s not enough to study black history from a radical perspective. We need to rethink our whole understanding of history, globally, in order to move towards a radical critique.

So it’s not enough. If people just study black history, they won’t get it. They have to understand the relationship between these movements and recognize that what we think of as “black history” is not marginal, but really central to the motion of the making of the modern world. That was the great gift of Cedric Robinson, and the great gift of DuBois and others.

The second answer is that I don’t know if reading ever fully, completely radicalizes anyone. I always think of this as a process, a process that ebbs and flows. Sometimes the very people who claim the mantel of radicalism could be slowing us down—in other words, they could be stuck. One of the lessons that Cedric gave us was that even those who claim the mantel of Marxism can also have a very limited vision. And the people who may have no relationship at all to Marxism may actually have a vision that we need.

I never pass judgment on people’s levels of radicalism. If we’re all here together thinking through it, then we’ll all be able to have the vision.

CM: Robin, truly a pleasure having you on the show this week.

RK: Thank you so much, this has been fun.

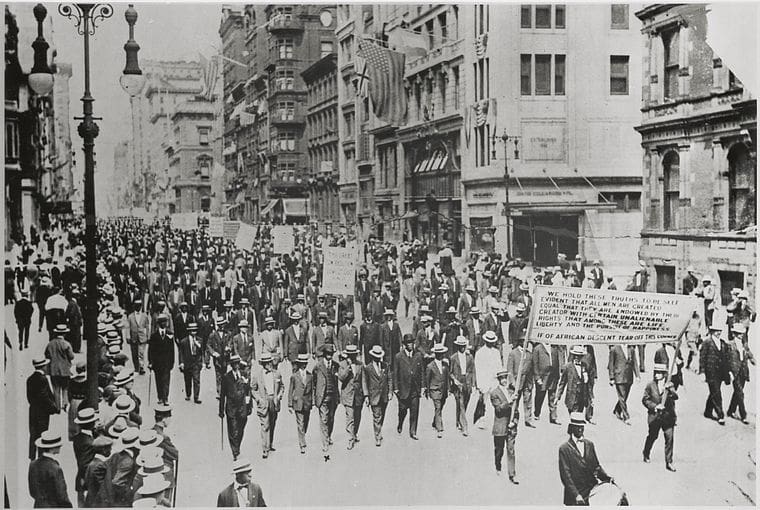

Featured image via the African American Intellectual History Society’s blog