Employed and Poor

by Andrei Bespalov for Takie Dela (original post in Russian)

translated by The Russian Reader (original post in English)

13 December 2017

According to official statistics, at least ten million Russians work hard all their lives but cannot escape poverty.

Russia has no clear criteria for poverty. The concept is absent from Russian legislation. There are poor people throughout the world, but not in Russia. We vaguely define them as “low income,” meaning people whose income is below the subsistence level. Each region of Russia has its own subsistence level. For example, for a person of working age to make it for a month in Omsk Region, he or she needs at least 9,683 rubles [approx. 140 euros]. In Moscow, the minimum income is twice as high: 18,472 rubles [approx. 267 euros]. If your income is lower than the officially approved subsistence level, you are living below the poverty line. Of course, this in no way means you cannot be paid less than this minimum for your work. You can indeed be paid less. Currently, the minimum monthly wage in Russia is 7,800 rubles [approx. 113 euros].

Story No. 1: Olga

“What are we talking about? I’m forty-five.”

Many imagine you have to go outside Moscow to find poor people, and the farther you get from Moscow, the more flagrant poverty you will encounter. This is not true. There are large numbers of people living below the poverty line in the capital. I should emphasize that, in this case, we are talking about Russian nationals, not about migrant workers from the former Soviet republics.

Take Olga. She works in a lab at Moscow Medical University. In her fifteen years there, she has risen from senior lab assistant to head of the lab. Olga’s monthly salary is 12,000 rubles [approx. 173 euros], and it is her entire income.

True, she gets the occasional bonus, but they come “a little more often than once in a lifetime.” Ordinary lab employees are paid 11,000 rubles a month [approx. 159 euros]. Such salaries are hardly a rarity in Moscow.

Olga was educated as a programmer. She graduated from Bauman Technical University, but she has not worked as a programmer for a long time. She has lost her qualifications and believes she cannot catch up. Olga worked as a programmer before her children were born. Her family had enough money for everything, and besides, it was an opportunity to earn money part-time. When her maternal leave was up, though, she was unable to go back to her old job: her department had been disbanded.

She was then able to get this job in the lab at Moscow Medical. Olga likes everything about the job—her colleagues respect her, and her work team gets along well with each other—except the salary. Management occasionally permits her to work from home. This is good for Olga: she does not have to spend money on commuting (Olga lives in Moscow Region, not in the city), which comes to around 300 rubles [approx. 4 euros] a day for the trip to the city and back on the commuter train plus a round trip on the subway to the university.

When her children were small, Olga did not try and find better-paid work, and when they were older, she tried, but was turned down everywhere she applied. To her surprise, she realized no one wanted to hire a woman in her forties.

“First, you can’t find work because of the children, who are constantly ill, and then you can’t find work due to your age. Although what age are we talking about? I’m forty-five!”

Olga had wound up in the category of people with no prospects. The only place she could get a job was a school. Olga worked there for several years before quitting. She had never been offered a full-time position, and her monthly salary of 6,000 rubles [approx. 87 rubles] was only enough to pay for her commute.

“I don’t want to leave these folks. It’s easy working with professors. They are quite cultured, decent people. It would be a pity to quit the job. I feel I’ve become a highly qualified specialist over the last fifteen years,” said Olga.

If it were not for her husband, a programmer, she would have a hard time feeding them and their two children. The family of four’s overall income is above the subsistence level, if only by a little. It comes to around 80,000 rubles [approx. 1,155 euros] a month (the per capita subsistence level in Moscow is 18,472 rubles, meaning Olga and her family make around 7,000 rubles more in total than the subsistence level). It was their good fortune both her sons were admitted to university as full scholarship students. Olga and her husband would definitely not have been able to pay their tuition.

Olga’s family took out loans to improve their living conditions. They started out in a room in a communal flat and, after several steps, moved into their own two-room flat. However, they had to rent housing for three years, since construction of their apartment building had been postponed. Renting meant additional expenses. Subsequently, Olga had to take out a loan to fix up the flat in order to move in as quickly as possible. That was five years ago. Of the original loan of 500,000 rubles, they still have 300,000 rubles [approx. 4,300 euros] to pay off. The monthly minimum payment is 20,000 rubles [approx. 290 euros].

In her free time, Olga tries to earn extra money by knitting. She says she is very good at it. But she is unable to supplement her salary by more than 4,000 or 5,000 rubles a month, and this happens extremely irregularly. Olga says a master knitter would have to work all month without taking a break to earn that kind of money. Everyone likes the things Olga knits, but people are only willing to buy them if they do not cost more than mass-produced Chinese goods—that is, they are willing to pay the price of the yarn. Olga is not ready to give up her job at the university.

It’s Unique The poverty experienced by employed people harms the economy and hinders its growth. This was the conclusion reached by the Russian Government’s Analytical Center in a report published in October 2017. “The poverty of workers generates a number of negative economic and social consequences, affecting productivity and quality of work; shortages of personnel in the production sector, especially manual laborers; the health of the population; and educational opportunities,” wrote the report’s authors. Olga Golodets, deputy prime minister for social affairs, has spoken of the fact that the working poor have no stake in increasing productivity. Judging by a number of recent speeches, the authorities are aware that grassroots poverty threatens the country. Golodets called poverty among the working populace a unique phenomenon in the social sector. A uniquely negative phenomenon, naturally.

Story No. 2: Nadezhda

“I have been humiliated my entire life.”

Nadezhda works as a history teacher at a technical school in Barnaul. She has been teaching for twenty-seven years, and her monthly salary is 12,000 rubles [approx. 170 euros]. Nadezhda has been named Teacher of the Year several times. The regional education and science ministry awarded her a certificate of merit for “supreme professionalism and many years of conscientious work.”

Nadezhda works with a cohort of students that includes many orphans and adolescents with disabilities: the visually impaired, the hard of hearing, and the deaf and mute. It happens that her class load is as much as eight lessons a day.

Nadezha and her eleven-year-old son share a room in the technical school’s dormitory. Nadezhda has been on the waiting list to improve her living conditions for fifteen years.

“Last year, I was ninety-fourth on the list. This year, I’m ninety-first. At this rate, I can expect to get a flat in thirty years or so,” she said.

Nadezhda thought long and hard about applying for a mortgage, but she decided against it, although the bank had approved a loan of one million rubles [approx. 14,500 euros]. But what income would she have used to pay back the loan, when the monthly payment would have been 21,000 rubles?

In Altai Territory, where Barnaul is located, 12,000 rubles is above the subsistence minimum, which has been set at 10,002 rubles for the able-bodied population. In addition, the state pays Nadezhda’s son a monthly survivor’s pension of 8,300 rubles after the death of his father. Officials cite this as grounds for rejecting her request that her son should receive additional social benefits. The family’s monthly budget is 20,000 rubles, so they should be living high on the hog from the official viewpoint, apparently.

In 2013, Nadezhda suffered a severe concussion involving partial loss of hearing and eyesight. She was struck by a student high on drugs, she said. She spent over two months in the hospital. Ever since then, she has had to take pills that run her 3,000 rubles a month.

“Working with classes in which there are many orphans is not easy at all. They demand your constant, undivided attention. When I say ‘demand,’ I mean ‘demand,’ and they get that attention. But then conflicts arise with the parents of other children: the class doesn’t consist entirely of orphans. They say I don’t give their kids enough attention.”

Over the course of her life, Nadezhda has never been able to earn enough money to buy a standard 600 square meter dacha plot. Thanks to her former father-in-law, however, she grows vegetables on his plot.

“I hear the call to be a patriot from every radio, TV set, and kitchen appliance. What are you going on about, guys? I have been humiliated my entire life, paid crumbs for a difficult, responsible job. I’m hit on the head by students, and they go unpunished. I’m told to quit if it doesn’t suit me: no one is holding me back. They tell me they will find a way to evict me from the dormitory, although they are unlikely to succeed as long as my son is a minor. I’m a teacher of the highest category, with a certificate of merit from the education ministry. Our family income exceeds the minimum subsistence income by 700 rubles, meaning that officially we are not poor. Thank you very much, it makes life so much easier.”

A Trend Since 2005, the poverty level in Russia has decreased threefold, note the authors of the study. At the same time, they write, “We cannot recognize as normal circumstances in which over ten million employed people have incomes that do not allow them to provide decent living conditions not only for themselves but for their families.” The researchers at the Russian Government’s Analytical Center have noticed a trend in recent years. There have been more people working in needy families, but “this has not vouchsafed their exit from poverty.”

Story No. 3: Igor

“Salaries at the institute are pitiful.”

Igor Kurlyandsky, a PhD in history and senior researcher at the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, cannot be categorized as belonging to the working poor. His monthly salary exceeds the minimum subsistence income for someone living and working in Moscow by 600 rubles. His monthly after-tax income is 19,300 rubles [approx. 279 euros]. There are freelance jobs, of course, but they are irregular and do not change Igor’s circumstances for the better.

“Generally, the salaries at the institute are pitiful. Doctors of Science and senior employees are not paid much more than I am, three or four thousand rubles more,” Kurlyandsky said.

FANO (Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations) is supposed to pay quarterly bonuses based on performance indices—for example, academic publications. But this year, according to Kurlyandsky, FANO has not paid out any of these bonuses, and it has canceled old bonuses as well.

“It’s wrong to demand that scholars publish frequently. They might work for a year in the archives, collecting material for future academic articles. Or they might take several years to write a book. I worked for four years on a book about the relationship between the regime and religion during the Stalin era. I will not be paid a fee for the book. I might get a salary bonus for it from FANO. But whatever it is, if you divided it by four years, it would amount to kopecks. The institute has nothing to do with selling books. Authors earn nothing except complimentary copies.”

According to Kurlyandsky, the Institute of Russian History, one of the principal historical research institutions in Russia, with many wonderful scholars on its staff, is itself a beggar.

“It literally has no money for anything. The state hardly finances it. Of course, for many years, its fellows can travel, for business only, at the expense of host institutions.”

“If memory serves me, the last time researchers got a raise was around fifteen years ago. Life becomes more expensive, but our salaries stay the same. Over this period there were several spikes in inflation, but our salaries were not indexed. I have to skimp on lots of things,” Kurlyandsky confessed.

Where Are There More Poor People? If you look at the situation by sector, the majority of the working poor are employed in housing services and utilities, education, culture and sports, agriculture, forestry, and a number of other sectors. The sectors with the fewest working poor are the resource extraction industries, finance, public administration, the military-industrial complex, and social security administration. Generally, the statistics say that since 2005 the number of working poor has decreased from eight million to two million, and the percentage of poor people from 24.4% to 7.3%, and this has occurred mainly due to the private sector, not the public sector.

Story No. 4: Svetlana

“We earn our 23,000 rubles a month and divide it among seven people.”

Forty-four years old, Svetlana works as a senior librarian. She arrived at the library immediately after graduating from a teacher’s college. Twenty years on the job, Svetlana has a huge amount of experience and a monthly salary of 8,300 rubles [approx. 120 euros].

“When I was a student, I imagine my future job as a perfect idyll: silence, lamps glowing on the tables, people reading, and me bringing enlightenment to the masses. It’s funny to remember it. I didn’t think about the money then, of course, but nowadays it’s the thought with which I wake up and go to sleep. My husband teaches at a university and makes a little over 14,000 rubles [approx. 200 rubles] a month. We have two sons in school. My dad is quite unwell, and my husband’s mom and dad are also quite ill. So we earn our 23,000 rubles a month and divide it among seven people—among seven people, because my dad and my husband’s parents have pitiful pensions, public pensions, despite the fact they worked in factories for thirty years. It’s my perennial puzzle. What should we buy? Medicine for the elderly? Shoes for the kids? Pay off part of the debt we owe on the residential maintenance bill? Buy decent trousers for my husband? I haven’t given myself a thought for a long while. Honestly, I wear blouses and skirts for ten years or so before replacing them. I can’t recall the last time I bought cosmetics.

“Earlier, we bore our poverty more easily, maybe because we were younger. So what there was nothing to eat with evening tea? Who cared that we dressed modestly? It was a style of sorts. We tried to make sure the children had better shoes and clothes.

“The most terrible thing right now is not that we are paid kopecks. My husband used to believe we would struggle through, that we would work off our debt. But then he burnt out. He forces himself to go to work. The children are perpetually dissatisfied, and our parents are always ill. Only I don’t pretend it’s okay, that everyone lives like this. I have caught myself sizing up how people are dressed on public transport, and at the store I look into their baskets. What fruits, meat, and wines they buy! We are always eating buckwheat groats with bits of chicken and meatless soups. I hate the dacha, but it really does put food on our table.

“I have no prospects. I won’t live long enough to be promoted to head librarian, because our head librarian is my age. I lack the strength for side jobs. My real job is not easy: there is lots of scribbling involved. Plus, we divvied up the jobs of the cleaning woman and janitors, so we either mop the floor or chop ice on the pavement. I crawl home barely alive. Frankly, I don’t see how my life could change, and I’m used to it. What worries me is my sons’ future. I’m horrified when I think that soon they will be applying to university. What if they don’t get full scholarships? We definitely don’t have the money to pay for their educations. So it turns out we have doomed our boys to the same poverty.”

It’s Shameful to Admit Nearly everyone with whom I spoke when writing this article asked me not to use their real names and places of work. They all made the same argument. First, it is shameful to admit you work for mere kopecks. Second, their bosses would be unhappy and punish them for “disclosing information discrediting the organization.” Many of my interviewees actually had signed such non-disclosure agreements, entitled “Code of Ethics,” at work.

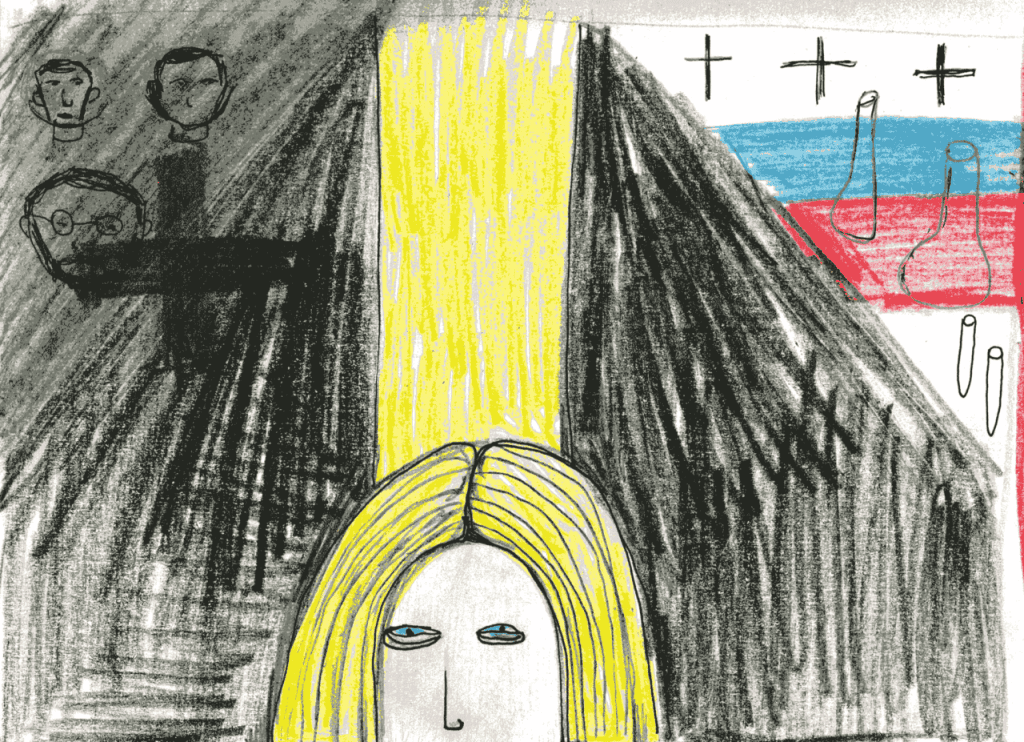

All illustrations courtesy of the artist, Natalia Gulay, and Takie Dela. Translated by The Russian Reader

Republished with permission. If you liked this article, please consider subscribing to The Russian Reader on WordPress and Facebook. It is a labor of love—love which ought to be reciprocated if the labor is to continue. Antidote Zine has been boosting selected TRR work for several years and hopes they will keep providing us and you with these invaluable street-level perspectives out of Russia.