Crossing from Idlib to Turkey, Fall 2017

by Samhar al-Khaled for Ayn al-Medina (5 September – 20 September – 10 October 2017)

and published shortly after on Alsharq (original posts in German)

26 December – 28 December 2017 – 1 January 2018

Arabic-German translation by Sara Osman

German-English translation by Antidote

Part I: What You Don’t Know Will Cost You

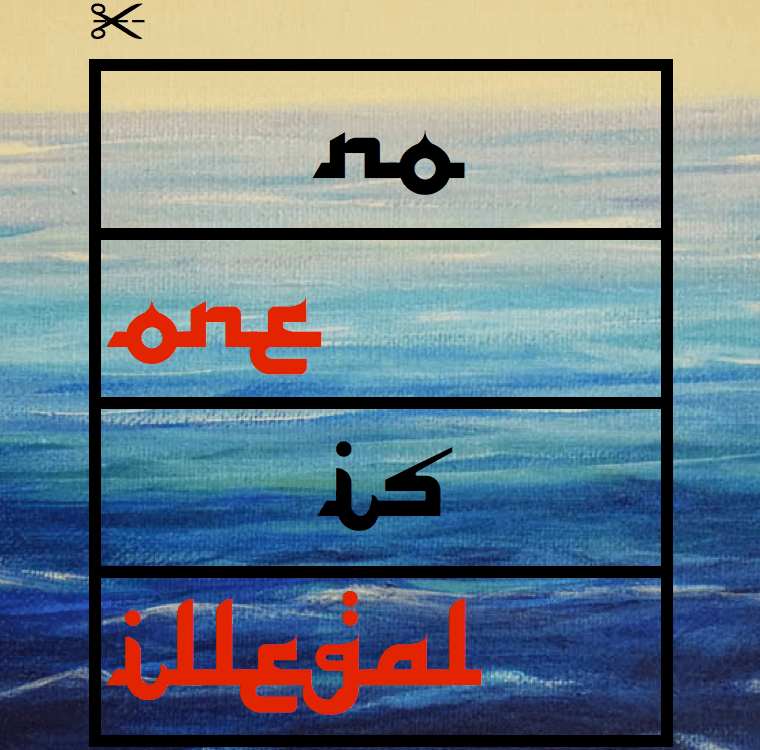

Millions of people have fled from Syria to Turkey over the course of the Syrian war. But the routes have been getting more and more dangerous since Turkey erected a border wall; an opaque network of smugglers and middlemen has established itself in the border region, which aids—or exploits—those fleeing for their lives. This is a refugee’s travelogue of sorts.

For the smugglers and their middlemen, those of us who want to cross the border to Turkey illegally are just customers, passengers. They say it is out of sympathy that they help us, but the way they behave is devoid of any sympathy. They don’t see us as anything more than people who are ready to pay a lot of money for their help.

For years, the provincial capital Idlib in northwestern Syria has been a stopover destination for Syrians aiming to get to Turkey. They come there from every part of the country, though there are especially many from Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Aleppo. For quite a while it was a rare exception that the Turkish government would try to prevent refugees from crossing the border in this region [further east it has been a different story of course. —ed.]. But last year Turkey closed the border and built a concrete wall in order to fully separate the countries from one another once and for all.

The world of “refugee aid” contains a lot of fraud and trickery—when, for example, a passenger refuses to pay once he arrives in Turkey, or when a smuggler vanishes into thin air the moment he receives money from a passenger. Sometimes smugglers pressure their customers to try again after a failed attempt to cross.

Out of geographical necessity, the smugglers themselves are mostly from the border areas. But since this is mainly empty countryside, customers don’t go there directly. They don’t know the smugglers working the border, and there isn’t enough lodging, transportation, supplies, or telecommunication capability around there. It should also be observed that in contrast to the smugglers themselves, their customers usually come from urban centers.

The thing about middlemen

Because of all this, over time a network of middlemen arose to introduce and negotiate between borderland smugglers and prospective passengers concentrated in urban Idlib. They promise a smuggler’s services to a prospective passenger; they also ensure for the smuggler that the passenger will pay the agreed-upon amount. This has led to the expansion of the people-smuggling economy. Figures participating in this economy, besides smugglers and passengers, are middlemen, drivers, land and real estate owners—or simply anyone who lives in Idlib and knows a smuggler.

Ordinarily, a middleman charges between $50 and $150 to establish contact between a smuggler and a customer. Smugglers and trail guides (who, by the way, also charge between $50 and $150), extort the highest possible sum from passengers before putting together a group that will cross together.

Routes have names like “the crawl,” “the cotton,” or “the tractor.”

Mostly unawares, I repeatedly found myself in the middle of this economy along with a number of other travelers. It was only later that I learned what every one of us had suspected even then: we are all the victims of these smugglers, who are making enormous profits off of us. I have since had this further confirmed: after several failed attempts to cross the border and after getting to know some smugglers and guides while in Turkish prisons (where I was as a result of said failed attempts), and after building relationships to middlemen in the towns of Idlib province, I know the market pretty well.

Escape routes are either named after the area travelers are supposed to cross, or after the manner of travel. For example, there is the route called al Harim (after a small Syrian border town), al Asi (the name of a river), al Kotton (“the cotton”), al Jidar (“the wall”), al Zahf (“the crawl”), al Rakd (“the run”), al Mashi (“the hike”), al Mashi al Taweel (“the long hike”), al Traktor (“the tractor”), al Izn (“the permit”) and al Bawaba (“the gate”).

The price of the route depends on how difficult the trip is for the passenger and how high the chances of success. The al Harim route, which is very tightly monitored, is at $300 per passenger the cheapest. Al Bawaba is the most expensive, at $3,000 per passenger. For routes costing less than $1,000, the middleman receives $250 from the smuggler. The amount the customer pays, however, also depends on how urgently he wants to get to Turkey and how well-informed he is, as well as what kind of financing is available to him. The price is also determined by the size of a travel group and how well it is looked after.

A successful crossing achieved by a smuggler will increase the price of a route. His success gets him more business—it then takes a few days for his new customers to realize that his previous success had been pure coincidence. The stars might then align for a different smuggler, and the process continues.

Trade in passengers

It is well known that passengers are also “sold” from smuggler to smuggler. I myself was a victim of this. At one point the middleman collected $500 from every passenger in our group, indicating that he was going to pass us along to a smuggler for this price. Only later did we discover that this was not a smuggler at all but yet another middleman, who had taken $400 per person—of which he paid $250 to the actual smuggler. He kept us hidden in a tiny border town for two days to make sure that we didn’t come in contact with any other middlemen or smugglers.

It’s getting more and more common for passengers to be sold down the line like this. All the middlemen and smugglers trust that no one will tell the passengers the true price of the trip. Instead they tell you that they never end up with more than $50 per passenger and that this money barely covers costs.

Hilariously, they all also constantly talk shit about other middlemen and smugglers, those bad ones who exploit refugees!

Part II: From Plan to Reality

Whoever wants to flee Syria for Turkey needs not only a lot of money and patience, but also good luck with smugglers. Sometimes smugglers simply lie to their customers, speaking of a wide river as though it were a dried-up irrigation canal, for example, just to motivate travelers.

Whether in the group homes where customers are lodged, in the the backs of transporters, or in the smugglers’ offices: everywhere, it seems, Turkey is so close you can touch it. Over and over again, customers fall for the embellishments of the smugglers: “Tonight you’ll be having dinner in Turkey” or “Tomorrow morning you’ll wake up in Turkey.” Negotiations then begin over how much money must change hands, how it will be paid, and which services are included in the border-crossing operation. Then the smuggler starts to explain the plan.

It often sounds something like this: on the al Harim route, first the wall between Syria and Turkey must be overcome. That’s handled. Then you must wait in the fields until the guide declares it safe to continue, whereupon you will meet up with a Turkish smuggler waiting with a car. Or, on the al Asi route, first you cross the eponymous river in a small boat, then crawl across some fields and finally arrive on Turkish soil. On the al Ayal (“the family”) route, you walk for around two hours and cross the border at an unattended spot. On the al Izn (“the permit”) route, travelers will cross the border in the vicinity of a Turkish police station, because there is an arrangement between a Turkish smuggler and security forces.

$50 smuggling permits from the Islamists

Some landowners use their private land in border areas for people-smuggling—although they can’t really prevent anyone from using it even without their permission. Many also flee across public land. But that only works if Hayat Tahrir al Sham [HTS]—an aggregation of Islamist rebel groups—allows people to traverse these areas.

For $50 per person, HTS issues written permits to smugglers on the condition that they do not charge extra for children. In practice, however, three children under ten count together as one adult. People are instructed by smugglers to be quiet about this when they pass the checkpoints that HTS operates to review these permits.

The smuggler hid me and other refugees in the back of a transporter. As we approached a checkpoint, he told us that other smugglers do not pay HTS directly. Instead, they pay the militiamen at the checkpoint a flat-rate bribe of $150 per group to pass the checkpoint without a permit. The system is obviously totally arbitrary: sometimes checkpoint guards demand an additional $100 per passenger even from smugglers with a permit, and force them to take injured fighters with them to Turkey.

As refugees get closer to the border, the smuggler begins to explain in more detail the route they will be taking. On the al Harim route, first you climb the wall, wait a little while, and then walk towards a particular Turkish town. In reality, however: first there is a wall, then a ditch four meters deep, then a metal fence with barbed wire, then at least six hours in brambly fields. Then you either have to climb another wall or crawl through a drainpipe in order to reach a section of Turkish countryside that is, after all, also being surveilled by the gendarmerie.

Regarding “legal routes”

On some routes, refugees have to creep for hours through cotton or pepper fields only to reach a Turkish military road where gendarmes patrol. If the gendarmerie appears to be inattentive for the moment, then the refugees proceed further; it is only then that it dawns on many travelers that the al Izn (“the permit”) route, for which they may have paid $2,000 or more, is actually just another illegal route. The smuggler had told them that they would be issued a legal permit from the Turkish authorities.

Smugglers guide many groups of refugees to this route, especially people from Iraq, in order to keep the Turkish gendarmerie busy. Whoever gets lucky on this route is then convinced that he crossed the border with special permission. Those who get arrested by gendarmes are sometimes refunded their money by the smuggler, who invents excuses for their having been detained, such as confusion or disagreement among Turkish police.

Smugglers use videos to motivate refugees to continue

On one attempt, as we set out to cross the border, many refugees started to turn back either because they saw difficult obstacles or heard gendarme gunshots. The smugglers then showed them videos featuring other refugees safe and sound in Turkey. Some were persuaded and continued on, even if they also suspected (not unfairly) that smugglers were intentionally sending some groups across while the gendarmerie was on alert in order to secure another group’s crossing elsewhere.

Many travelers set out to cross the border without having been given a clear or accurate idea of the route by the smuggler or guide. This happened to me as well, when I attempted to cross the border with a group on the al Tulul (“the hill”) route. The middleman explained to us that we would first “jump” over a wall, then climb down an irrigation ditch that was mostly dried up; the water would be waist deep at most. After that we would walk half a kilometer to a cornfield, and were not to worry about gendarmes or their warning shots. The police station would be a kilometer away, and as soon as we got to the cornfield the gendarmerie would give up their pursuit because we would be too difficult to find and catch. Once we had gotten through the field, we would come to a wall and, climbing over it, would arrive in a Turkish town.

The “dry irrigation canal” was actually a river

The smuggler leaned a ladder against the wall, climbed up, cut a gap in the barbed wire running along the top of the wall, and signaled to us to jump through to the other side without him. Then we climbed down the ditch and discovered in front of us not a dry irrigation canal at all, but the al Asi river.

Also, the police station was much closer to where we were than the cornfield, which itself was enclosed by a barbed-wire fence. The farmers, who were right there in the field, set their work aside to help the gendarmes catch and detain members of our group. At this point I was still struggling my way across the river, and hid on the bank to watch and wait. Ultimately, I too gave myself up to the furious gendarmes.

Part III: The militarized border regime

Even once you’ve made it across the border from Syria, you’re still a long way from safety. Turkish border police are hunting migrants all over the border region. And they do what they want with those they catch.

Before setting out themselves, most travelers have already heard stories of others’ experiences fleeing. Depending on the route, there are minor differences with regard to how gendarmes treat the people they catch. Based on this, distinctions are drawn about which routes are for families and which routes are for young people.

The closer travelers come to the border, the more clearly they can hear the shots of the gendarmes. Ordinarily, travelers can already tell the difference between light and heavier weaponry, for example NATO rifles, sniper rifles, and machineguns. While the group is hiding and waiting for a certain moment to move further, the guide explains that the gendarmes usually only shoot into the air—but if people try to run away to avoid arrest, they might aim at them.

Rumors of shoot-on-sight orders

A young man told me once that his friend was shot while on top of the wall between Syria and Turkey. The gendarme who shot him insisted to investigators that he fired warning shots in the air first, and that when he shot the young man it was to wound and not to kill.

Guides beg their passengers repeatedly not to reveal their identities to gendarmes, because they could be severely punished. It seems the gendarmerie has stopped even asking about the guides, because they know that refugees won’t tell them anything. Or perhaps they have concluded that smugglers send their passengers to the border entirely unattended.

With the hundreds of refugees who have been wounded or killed by gendarme gunfire recently, observers assume that a shoot-on-sight order may have been given on the Turkish side of the border. Based on the many incidents that I have personally experienced, however, I doubt this is the case.

Turkish police in Syria?

There was this one time we were on the al Izn route. We were still at least four kilometers away from the Turkish border when we came under heavy gunfire from a hill on Syrian soil. While we were taking cover, we saw another group of refugees running away, leaving one man behind who had been hit in the thigh. Rumors circulated that the shots had come from a Syrian border town whose smuggling business stood in conflict with that of HTS. Others countered that it had been Turkish gendarmes who had opened fire. This would cast doubt on whether the shots had indeed come from the Syrian border town; none of these accounts is impossible.

Other interpretations among smugglers assume that Turkish-Alawite police or gendarmes were responsible for the shooting. There are groups of Turkish gendarmes who do cross the border in order to steal money and belongings from refugees. Smugglers and rebel fighters have frequently responded to such incidents by opening fire on Turkish gendarmes themselves.

Sedatives for the children

At one of the stops along the escape route, guides asked parents to give their children sedatives so that they wouldn’t cry when the group was near the border. Otherwise the gendarmerie would notice the whole group and arrest us.

As soon as gendarmes spot a group of refugees with their binoculars, they shoot in the air or in the vicinity of the refugees. Then they bring the travelers to a police station, where as many as three hundred other people may also be brought in the course of just one night. I was one of these people once. In one such police station, the number of prisoners at any given time could number in the thousands.

Sometimes refugees are taken directly back to Syria, or, after hours or days, are transported in buses to a Syrian border crossing. However, this happens only once they’ve been thoroughly searched with a metal detector and their cell phones have been confiscated. All their names are also recorded, and their photos taken.

Hit with a shovel and made to clean toilets

This indicates how rigorously the gendarmes hold themselves to the laws prohibiting abuse of prisoners and requiring the return of belongings—not at all. And this is on the routes that families take. On the routes that young people use, the gendarmerie is even more violent, especially when the officers look away. Once I was in a group in which one young man was hit with a shovel.

Ordinarily, arrested travelers are detained for hours or days on the basketball court at the police station. The gendarmes there behave totally as they please. Some brought us food and blankets at night while others forced us to mow the lawns around the police station or clean the toilets.

Not long ago there was an incident when a gendarmes’ truck began following a van full of refugees who had just reached Turkey. The gendarmes rammed the van from behind and opened fire. After nine refugees were wounded, the car finally stopped. Two passengers died.

One of the survivors reported that police and media showed up to the scene. But the gendarmerie was allowed to lead the refugees away and hold them in custody for six days, during which they were taken to six different hospitals. They were promised that they would be taken to refugee camps in Turkey, but ultimately they were forced to put their fingerprints on documents pledging to voluntarily leave Turkey.

German version edited by Maximilian Ellebrecht

Note from Alsharq: This series of articles appeared on Ayn al-Medina in September and October 2017—therefore preceding the incursion of Turkish troops into Idlib [and Afrin]. It is difficult for us to imagine how the border situation there has developed since then. But at least for the time it was written, the situation described here presents a slice of reality.

Featured image: Andreas H. Landl/Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 (2012)