AntiNote: As Turkey’s so-called Operation Olive Branch continues to steamroll town after town and fortification after fortification in Afrin despite both the YPG’s reputation as a fierce defense force and their having completely debased themselves by accepting support from Assad regime forces, we thought it as good (or as bad) a time as any to unearth this testimony from a German internationalist YPG fighter from the now nearly forgotten battle of Raqqa.

We had been sitting on it for several months, uncomfortable with the prospect of appearing to root for one revolutionary faction over another when there has been so much strife and betrayal among them in northern Syria, since 2016 and the fall of Aleppo if not before, with powerful fascioid imperial players—Russia, the US, Iran, Turkey, Israel, and others—imposing their own dubious visions and interests on vulnerable and desperate local forces and pitting them against one another in ways that always somehow benefit the one entity which in a perfect world would be the singular focus of all righteous hostility: the genocidal Assad regime.

Without re-litigating any of this history, we simply want to emphasize the value of these sorts of street-level accounts, especially ones displaying as much simultaneous ambivalence and resolve as this one, and encourage our readers to seek out these voices wherever possible amid the fog of state media disinformation (whether Syrian, Russian, Turkish, PYD-Kurdish, KRG-Kurdish, American, Israeli, or any other). It seems imminently possible that both Afrin and the Eastern Ghouta will soon be fully back in the hands of fascist mass-murderers. May the stories and legacies of those who resist continue to persist even as the “victors” attempt to erase them.

Love in a Hopeless Place

by Peter Schaber for Lower Class Magazine

3 October 2017 (original post in German)

I could have been back in Germany a long time ago. When I traveled to northern Syria eight months ago, I had planned neither to stay as long as I have nor to pick up a gun. At first I was working in my chosen field, as a journalist. But I also started pitching in as a construction worker, as a social worker, as a cook, a janitor, a translator. The revolution has many facets; you have to undertake many different tasks, including ones with which you have no previous experience.

The labor of defending a revolution on the battlefield against those who seek to smother it was something I had to learn from scratch. I didn’t know how to use a rifle, a hand grenade, or a bazooka. So I went to get trained. Then came the day that I, along with three other internationalists, got into a caravan headed for Raqqa.

One hundred kilometers to go

“Die Heimaaaat ist weit…” Heval Ciwan belts out the opening line of a marching song of the Thälmann Brigade [German communist internationalists in the Spanish civil war] as we careen along the Assad Highway towards Raqqa. “Doch wir sind bereiiiiiit,” the other internationalists—Kajin, Hogir, and I—join in. We are each wearing our rext, an ammunition belt of four magazines; a Kalashnikov is propped casually in the front seat, and Heval Botan, a 17-year-old sniper from Hasakah, passes out Pepsi and rolls of biscuits. The comrades native to this region follow our vintage internationalist anthem from Spain with another one from Rojava: “Kec u xorten soresvan…” I don’t feel nervous anymore, just curious and resolute.

Thirty kilometers to go

Lush green landscapes surround Raqqa. The waters of the Euphrates and an intricate irrigation system breathe life into the area. Trees gather in patches of forest; between them are vegetable gardens, cornfields, meadows. Men and women sit together in front of tents of canvas and hide, surrounded by sheep and cows. Everything seems normal. Children and youths greet us on roadsides with the victory sign. Heval Dilser waves back, then turns to us and says, “Don’t take that too seriously. When Daesh was here, they used their one-finger salute as a greeting. Now it’s two.”

Five kilometers to go

We exit the bus. We are somewhere in the Raqqa suburbs. A few hundred meters away begins the swathe of rubble that was once a city. We greet our forward commanders, and proceed to what turns out to be our quarters for the night, the roof of a ruined apartment building which serves as an outpost directing units in the southwestern sector of the siege ring around the remaining ISIS fighters. From our mattresses, we stare intently out into the pitch dark city. There is a flash. Guum. Impact. A building collapses. From this distance the bombardment is already impressive. Soon we would get a taste from closer up.

* * *

At the front

Many of the things you learn in Rojava come at a slow drip, over weeks and months. Not so for learning what the front means in a war like this—this crashes down on you all at once. Just a second ago you were out there in normal life. Now you’re in a war.

When I arrive in the war, it is evening. Between the occasional artillery hits, it is silent as twilight descends on Raqqa. The airplanes, drones, and helicopters have their night shift in front of them. The small-arms battles that break out in fits and starts during the day now take a breather before it really gets started. The city swiftly darkens. The contours of the Milky Way come slowly into focus in the starry sky unpolluted by city lights. Now, between eight p.m. and seven a.m., those of us here at the front are on watch. During the day we have barely anything to do, because Daesh doesn’t move. The jihadists sit underground, invisible, lurking. When the sun leaves the sky, the assaults begin.

Nighttime in Raqqa has a peculiar aesthetic. The ruins are cast in moonlight; there is no electric light at all. The weather is comfortable; there is an occasional breeze that makes it a little brisk. There is barely a sound in the already dead city. No one is speaking; no television bothers the neighbors; there are no children yelling. You could almost conclude that nuclear war or a virus has extinguished humanity and you are alone in the ruins.

But the silence is an abstraction. It exists only in the few moments here and there when there is a pause in the detonations, the bombs and shells that rip holes in buildings, streets, and people night after night, day after day (less, but still). The symphony is played on many instruments: rocket-propelled grenades and sniper rifles, BKCs and Kalashnikovs, mortars and howitzers fired from some suburb; helicopters that often fire dozens of rockets in a row…

…and the airstrikes. “There’s another plane in five minutes,” says our commander. “Lie down.” We lie down on the ground; some fold their arms behind their heads. I keep my mouth open, as a comrade had advised me, for the shockwave. When a bomb drops, first you hear the whistling, then the sky lights up; a shimmering light radiates from the point of impact across the horizon. Then comes the sound of the explosion, rending the air; then comes the shockwave—the walls bend. Only now do you hear the jet flying off.

Banality, routine, cats

My job in this detachment is simple. A typical worknight looks something like this: I kneel next to a pillar and peer into a black hole. I’ve chambered a round in my AK; a comrade from the YPJ covers the balcony behind me, which looks out onto the street in Daesh territory. We are on high alert. ISIS fighters had attacked the guard post next to ours with an RPG and sniper rifles. The black hole is a staircase, which is barricaded below. My task is to decide, if I hear a noise, whether the enemy is coming or whether it is a cat. If it’s the enemy, I have to either shoot or throw a bomb.

I sit in front of the hole for five hours, the walls around me shaking under artillery fire and aerial bombardment. There is a creak and a rumble from down in the hole, and the sound of hundreds of empty plastic bottles clattering. Tonight it is only cats—but cats that sneak the way people would. Cats who cry like people imitating cats. And cats that knock down barricades the same way people knock down barricades. “If I were in charge of Daesh, I would give every fighter a backpack full of cats,” jokes a member of our group: “If you accidentally make a noise during a sneak attack, pull out a cat, squeeze it so it mews, and let it run off. Guards will think, ‘Hey, it was just another cat,’ and then wham, you blow them all away.” I start hating cats.

Even if on the first few nights you jump at every noise, eventually you get used to the acoustic backdrop. You learn to distinguish. Animal. Trash blowing in the wind. Doors opened or shut by the wind. Human. Even the melody of the air war, repeating on endless loop, soon fades into monotony, you don’t notice it anymore. If you’re not on duty, you sleep through the bombs.

You don’t see much of the enemy. Only a few positions have night vision equipment. Most simply shoot at sound and motion, or at the muzzle flashes of the enemy when they are attacking. We mostly get to know Daesh through the clues they leave behind in the buildings we take when we advance.

In one former Daesh position, we find an Azerbaijani passport and—as always—all kinds of pills. Painkillers, opiates, muscle relaxants, stimulants. ISIS battle dress is strewn around the place. It must have been cast off in a hurry, maybe he stripped completely down. We snoop around the rest of the building and come across a small treasure: a box of materials for foreign ISIS members. Both fat volumes and pamphlets, guides to the Islamic State’s way of thinking. Thick books of rules on how “illegitimate sex” is to be punished; a booklet attempting to prove, with passages from the Koran, that suicide attacks are not haram; instructions on where to strike an infidel if you are attacking with a knife. Also, a handwritten recipe for chocolate-banana brownies.

We pore over everything carefully. It all strikes us as rather absurd. Heval Ciwan laughs. “Listen to this awesome shit!” he exclaims, and begins reading aloud in English: “How to react when you encounter the enemy. Rule one: Keep calm. Rule two: Think of the prophet very often. Rule three: Be patient. And nooooooow, the last rule.” Ciwan pauses for dramatic effect. “Massacre the kafir.”

“You could print that on a t-shirt! ‘Keep Calm and Massacre the Kafir.’”

Kafir, by the way—the unfaithful, infidels—are not just us communists as well as all atheists, Christians, Jews, and what have you, but, as we gather from another of the textbooks, also “ninety-five percent of Muslims today.”

In the box of propaganda, we also find clues as to its owners: a Dutch couple who had taken up the path of the Caliphate. We find letters in Dutch, in which the two complain about their very young son. His enthusiasm for the Islamic lifestyle leaves much to be desired. When he looks at women, he shows an unseemly interest. The letters read like reports on the development of a child into an Islamist. The child’s school notebooks document his early progress learning to write Arabic. On the first page of one, he has meticulously drawn a Daesh flag; on the pages that follow appear only cats with a dozen paws and antennae like an alien’s.

The war is (also) in our heads

Once you’ve been a few days at the front, the actual physical war against the Islamic State starts to seem pretty unspectacular. It has clear and modest dimensions. We sit in buildings which together form a ring around the still-remaining militia positions. We turn these buildings into little forts and trade off watching the surrounding streets and buildings. During the day you do next to nothing. During the night, you might shoot, if something happens, or throw a bomb.

The war against Daesh is violent, but its violence is banal. Of course, there is an enemy who wants to kill you. He wants to blow you up with mines or rockets. He wants to drop bombs on you from homemade drones. Or the classic: he wants to shoot you in the head, the belly, or the heart. None of that is particularly delightful. But it’s not the worst thing. Because this enemy stands in open conflict with you. You can defend yourself. You too have a rifle. You are not an object, but the subject of your own actions. You are here for a reason that has to do with your deepest convictions. And as long as they remain firm, your military opponent has nothing on you.

The war that’s much harder to fight is a different one, one that cuts more to the core, because it is precisely these deep convictions that it assaults. My comrades and I came here to defend a certain way of life, a project that could revolutionize all of our lives and our life together. We knew the Kurdish guerrillas from the Qandil mountains of Bakur—some of us through direct experience, some at least through stories—and they do not separate the military dimension of struggle from the political and social imperatives of revolution. That the PKK, despite its enduring and bitter armed struggle, has not sacrificed its collective principles—community, critique and self-critique, education—to the logic of war is what makes it so strong. In the military sense as well.

But that takes time. Because it means, fundamentally, that anyone who goes to the mountains is attempting to overcome the liberal, feudal, sexist, capitalist, racist, and other oppressive attitudes they have inherited from class society. The education of a guerrilla takes months, years, a lifetime.

The war in Syria has been catastrophic for this base of cultural knowledge and pedagogy. First of all, hundreds if not thousands of experienced activists have been killed in countless battles—Kobanê, Manbij, Tabqa. Furthermore, swift advances have swept thousands of people into the military structures, people who have perhaps taken up arms for reasons completely divorced from ideology: money, self interest, or simply because it is a survival tactic to sign up with the most strong and victorious militia in your region.

A war that is being waged on so many fronts has distinct dynamics. The biggest problem in Raqqa is not the military strength of Daesh. The true horror of this hell lies in the fact that the war, by nature, is destroying the life that we are supposed to be fighting for here. The thousands of often very young (and, in a relatively recent development, mostly Arab) soldiers serving in the ranks of the YPG and SDF are a reflection of society in Syria. They have by and large not enjoyed much education of any kind, let alone military training. They know little of the ideals of the movement for which they are ostensibly fighting, let alone live by them. The front is a filthy place, a place that kills friendship and solidarity.

The influx of thousands of people whose consciousness was formed by socialization within other brutally oppressed societies of the Middle East threatens to explode the seams of the unifying fabric that the mountain guerrillas have painstakingly quilted, work that the YPG aspires to carry further: the synthesis of civil service, the creation of a new mode of social existence, and armed struggle into one revolutionary praxis.

The toughest battle that we have to fight in Syria today is against the collapse of our own ideals, the fight against becoming another normal militia among other militias, the fight against a mentality that subordinates everything to the exigencies of war. We had to fight this fight within our own ranks in Raqqa. This was and is the real war facing us on all fronts. And it has taken us all to the limit.

We became sour, withdrawn, hostile. We developed prejudices. The immediate problems were so severe that we forgot to analyze their roots. We started to hate people and not the conditions that had made them who they are. Only later, from a distance, would we start once again to think: why does this kind of wretched behavior exist here, among the soldiers of the revolution? And doesn’t the circumstance of these people being as they are—doesn’t it have its roots in colonialism and exploitation by the countries we ourselves came from? And, most urgently: with whom would we rather do the collective work of making the revolution, if not with precisely these people?

The question of alliances

Besides the fact that life on the front refused to reflect our—admittedly naive—expectations, there was also the presence of the Americans to contend with. We could understand the necessity of this cooperation, but it was an emotional burden on all of us. It was not easy for us to stand on the same side as these murderous oppressors. We tried, at least, to reason with and educate those who clung to the illusion that Washington’s bomber pilots and artillery gunners were our friends.

There were young comrades who celebrated at the din of a detonation. We couldn’t really hold it against them. Many fighting at the front had no ideology, no education. For them it was simple: over there is Daesh, and the roar of a bomb blast means that now there are fewer of them. This may have been true, but we still made an effort to point out: “The Americans, for the time being, have similar interests to ours, as far as the fight against Daesh. But all these bombs, cannons, rifles, airplanes, howitzers, and tanks were not contrived with people’s liberation in mind. They oppress people. At some point they will use all these weapons against us, just as they have been used thousands of times against anyone who opposes imperialism, just as they have already been used for over forty years against the PKK in northern Kurdistan.”

And as if any further evidence were needed of US imperialism’s indifference to the lives of Syrians, it was delivered to us in the form of a strange sound. When we first heard it, all we could do was stare at each other, dumbfounded. What was happening? Airplanes were circling over the pocket, louder and probably lower than the bombers. Then the sky lit up red, and for three, four, five seconds the world was suffused with an ear-splitting noise that sounded as if a giant were ramming an electro-shock device into the belly of the city. The letters needed to spell the onomatopoeia do not exist, but it was something like “WWWWFFFFRRRRVVVVWWWWRRR.”

The day after hearing it for the first time, we asked Kurdish friends about it. They knew the sound all too well, but no one knew which weapons system made it. They too thought it must be something electric. Weeks later we found out what we had been hearing: the GAU-8 Avenger Gatling gun of an A-10 Warthog. And this weapon fires depleted uranium—radioactive munitions. Right next to the Euphrates, the lifeline of the entire region.

So, even setting aside that Raqqa was ideologically and psychologically wearying, dirty, unhealthy, dangerous, and—above all, as friends were falling—sad, our own “allies” were poisoning us with radiation.

Love in a hopeless place

But though we could now say that it was a mistake to go there, the opposite is true. It had been, for us internationalists, a duty. And I can claim to have found something in all that muck, something more important than all the difficulties set in our way: the love of comrades. What helped me get through this time was nothing other than our cohesion, our solidarity as friends, as companions. When I think of Raqqa now at some distance, I think above all about friendships. I think of the comrades that walked the path with me into that apocalyptic city of ghosts and monsters. I think of Heval Ciwan, with whom I had already shared, in the preceding months, the epic starry skies of the Şengal [Sinjar] mountains and the poor-hygiene-induced diarrhea of military training. I think of Heval Kajin, the best ramen chef in the entire siege ring around the dying caliphate. And I think of Heval Hogir, who should absolutely be the person tasked with painting splendid murals on the walls of Raqqa when it is someday rebuilt.

The friendships that connected us when we reached the edges of the embattled Syrian metropolis were still quite fresh. But they were, from the beginning, ones that had been stirred by a common goal, a concrete utopia. We had only known each other a few months; perhaps two of us had spent more time together than that. But we nonetheless became, in the coming weeks, each others’ everything: comrades and soulmates, teachers and students, caregivers and psychologists. And we got to know others who won our hearts within a short time as well. Without these people, without hevaltî, of whom there are far too few at the front, you would fall apart.

To have borne Raqqa, you do have to be a little bit crazy—which makes it all the more important to resist drifting away completely. The risk of giving in, of falling off the deep end into the abyss of rank bestiality, is a real one. When you have each other for love and support, though, it is possible to stay balanced even at the edge of lunacy. And of course in retrospect it produces the wonderful feeling of collective accomplishment: we licked this thing together. As rough as all of it was, they can’t take that away from us.

And political friendship is yet more than that. Because even when you are no longer in the same place, even when you no longer hear from one another because the necessities of the revolution have separated you, you still stay connected. When we left our nokta, we left good friends behind—for example Heval Leswan, our last team commander, who we started to miss before our truck had even crossed the city limits. We were in the same place as him for maybe ten days. But ten days, if you are spending twenty-four hours a day together in an extreme situation, are half a lifetime. When we departed unexpectedly, he pressed a keepsake into my hand; we kissed each others’ cheeks and gave the serkeftin [victory] salute.

We got into the truck. Leswan stood at the entrance of our post, his Kalashnikov cocked and pointed skywards. “Don’t shoot. We shouldn’t waste ammunition,” admonished the driver. Leswan glanced at him sharply and said, “My comrades are leaving.” He stood tall, faced forward, and squeezed the trigger. One round, two, three. Perhaps we will never see Heval Leswan again, nor he us. But just as he will always fight for what is important to us, we will always fight for what is important to him.

* * *

Thirty kilometers away

We sit in the open flatbed of a Toyota Hilux, and the nightmare recedes, kilometer by kilometer, from our lives. The critical remove needed to soberly analyze everything that just happened is still a ways away. The life-threatening (indeed often deadly) lack of discipline, the brutish behaviors, the feudal attitudes, and the appalling, description-defying hygienic conditions—we are free of all this now. We are glad to leave this feculence behind us. We feel a distinct but inchoate rage towards certain comrades, but we nonetheless begin to see some of the positives.

“It’s really remarkable,” says Hogir, “the difference between life among the guys and that of comrades in the women’s units.” We agree. The YPJ comrades were, as elsewhere, the avant garde in Raqqa. They are more organized, more disciplined, and take the principles of the party more seriously.

One hundred kilometers away

We keep the discussion going. Anger and frustration at the immediate threats posed by the behavior of some fellow fighters continues to boil off. The fog begins to lift from our vision. What was at the root of the problems? We begin to move away from “We’ll never let ourselves get caught up in that kind of situation again” and towards “How could we organize better under these sorts of conditions, and change something?”

This time it is Heval Kajin who strikes up an old Jewish partisan song. Ciwan and I don’t know it, but it is gorgeous. “Sage nie, du gehst den allerletzten Weg / wenn Gewitter auch das Blau vom Himmel fegt. / Die ersehnte Stunde kommt, sie ist schon nah / dröhnen werden unsre Schritte, wir sind da.”i After that, we sing—as well as we can—Leonard Cohen’s “The Partisan.” “I have changed my name so often / I’ve lost my wife and children / But I have many friends / And some of them are with me.” I consider belting out Rhianna’s “We Found Love in a Hopeless Place,” but think better of it, the mood’s not right. The sun goes down. We drive homewards, wherever that’s supposed to be.

Two hundred kilometers away

A strange feeling starts to creep in. Just a few hours ago, I wanted only one thing: to get out of Raqqa. But then, of course, I was still in Raqqa. Now I feel as if I were running away from something. Not Daesh. Not military struggle. But rather from the much more difficult struggle around changing the living conditions and behaviors on our own front. I had completed my tour of duty, I did not leave before it was over. But still—I had fled something. Others, who I had gotten to know and love, were still there. And many thousands more would go back, whether to Raqqa or to any other comparable places. It had been a privilege simply to be able to go—just as it is a privilege to be able to go, at some point, back to Germany.

I find comfort in one thing: that the struggle for a new life is not one that is possible to flee from. It is waiting for us wherever we go. And if we don’t lie to ourselves, if we don’t withdraw into some insignificant bubble populated only by the like-minded, if we don’t become traitors, this struggle will be with us through our entire lives. For this struggle, Raqqa made a very good classroom.

Four hundred kilometers away

We meet up with our comrades. Many have come, friends as well, who we hadn’t dared to hope we would see again so soon. We swap stories, including with others who have been to the front. I recognize something: what I saw was only a tiny sliver of this war. For some warriors who have conducted offensive operations, assaulted enemy positions, the focus is different. “I don’t want to diminish the problems you speak of,” says Heval Cihan, an experienced YPG fighter. “But you guys were on guard duty. When you’ve got to storm a position, and people are dropping like flies next to you, then other problems sometimes fall to the wayside.”

I am still totally exhausted, but it begins to dawn on me that I had, in Raqqa, been afforded a vision of reality in the Middle East. Definitely just a sliver of it, but much more than in the many preceding months combined.

Home Sweet Home

“This is how I see it,” begins Cihan, an experienced international cadre leader of the Kurdish movement, addressing all four of us returnees. “You witnessed and got to know some of the contradictions that the Kurdish movement has been working on for forty years. This is the Middle East. We from Western countries have been able to lead a life that, for all its difficulties, is nowhere near as fucked up as the life many are forced to lead here. Furthermore, it is only because the countries we come from have always exploited and robbed the Middle East that we have been able to live as we have and the people here have to live the way you just saw. If we can go to the front as revolutionaries and endure even just a tiny portion of this pain, it makes us stronger. And not only that, it helps us better to understand our roles in shaping this reality. This is a price that we must pay.”

That we—and many other (even Kurdish) cadres—have yet barely risen to this task is obvious. Cihan criticizes them as well: “There are the sloganeers who just toss around catchphrases. And there are also those who, out of racial prejudice, refuse to work with Arabs. For them, it’s like, ‘That’s the Arabs for you, they live in filth. Send them to the front and be done with it.’ But what was Kurdish society like before the PKK started to transform it? It had completely resigned itself to oppression as well. Today’s advancements took forty years to achieve. And now the task is this: to prepare for the next forty years, during which we will take part in transforming other Middle Eastern societies.”

And for the next one hundred years that it will take to do the same with us Germans.

Translated by Antidote

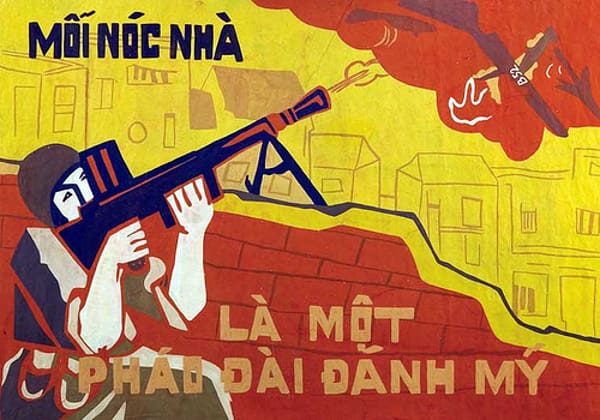

All images via Lower Class Magazine

i This song, written by Hirsh Glik in 1943 Vilnius, was famously sung (in Yiddish) by resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto. Several English versions exist, including one by Paul Robeson: Never say that you have reached the very end / When leaden skies a bitter future may portend / For sure the hour for which we yearn will yet arrive / And our marching step will thunder: we survive!