Eastern Ghouta: New Dimensions of Brutality

by Harald Etzbach for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s website

12 March 2018 (original post in German)

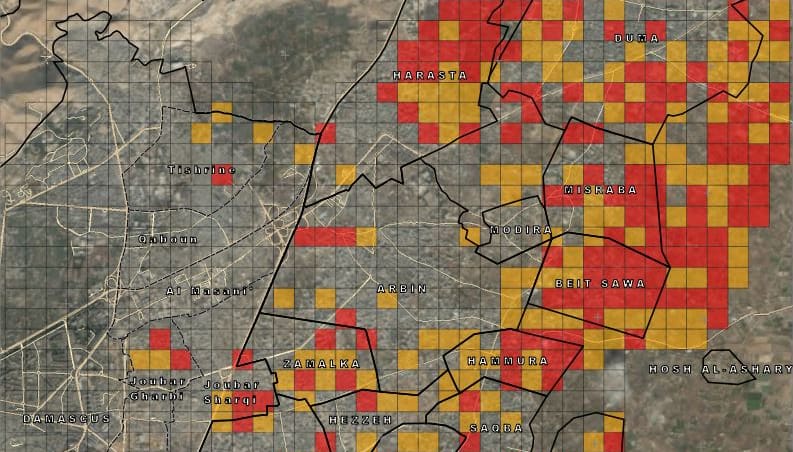

Seven years after popular uprisings began against the Assad regime, the situation in Syria has reached new dimensions of brutality. In the eastern Ghouta, a rebel-held pocket in the immediate vicinity of the capital Damascus, the regime has been waging a campaign of annihilation against the civilian population since mid-February. A map produced by the United Nations Institute for Training and Research [UNITAR], based on a comparison of satellite images from 23 February and 6 March 2018, shows that the most recent bombardment has focused above all on residential areas in the eastern Ghouta. According to Doctors without Borders, in the first two weeks of the renewed escalation (18 February to 3 March 2018) 1,005 people were killed and 4,829 were injured—that is an average of 71 dead and 344 injured per day. It is highly probably that the actual numbers are much higher, since the organization has only compiled data from its own affiliated hospitals.

Almost 400,000 people in the eastern Ghouta live under daily bombardment by the Syrian and Russan air forces—and this after already nearly five years of being subjected to siege by the Assad regime. During these years of siege, the eastern Ghouta has endured not only uninterrupted assaults with conventional weapons but also several chemical weapons attacks [most famously and egregiously on 21 August 2013]. Although the Syrian and Russian regimes insistently claim that these attacks were staged by rebel groups, overwhelming evidence indicates that the Assad regime and its allies are responsible.

For years, the Syrian government has been blocking the delivery of food and medical aid to the eastern Ghouta, which has driven the prices for basic daily necessities to astronomical levels and dramatically worsened the already dire situation the people of the region find themselves in, especially in recent months. Even after the recent Russian declaration of a five-hour ceasefire, the situation in the eastern Ghouta remains catastrophic. Not only was the ceasefire little respected by the Assad regime and its allies, but on 5 March the first aid delivery to Douma—the largest city in the eastern Ghouta—had to be called off when Assad’s forces resumed artillery fire, contrary to the arrangement. Of the 46 trucks in the UN convoy organized by the International Committee of the Red Cross [ICRC], only 32 could be unloaded. Even before that, seventy percent of the aid—including medical supplies like first aid kits and surgical instruments as well as insulin and other medications—had already been confiscated by the regime.

A second delivery of aid, this time only thirteen trucks, arrived in Douma on 9 March. It consisted of the food packages and medical supplies that had not been unloaded four days prior. Immediately after the convoy left the area, attacks resumed.

The next day, 10 March, the bombardment escalated again even though an arrangement had been reached between rebel groups and a delegation accompanying the UN aid convoy that would have seen Hayat Tahrir al Sham [HTS] fighters expelled from the eastern Ghouta. The presence of approximately two hundred HTS (an alliance spearheaded by the former Jabhat al Nusra, an affiliate of al Qaeda) militants has always been the pretext for Syrian government and allied attacks on the eastern Ghouta, and HTS has consistently been explicitly excluded from past ceasefires.

The current situation in the eastern Ghouta is becoming increasingly reminiscent of the strategy of the Syrian regime and its allies at the end of 2016 in Aleppo: siege, starvation, bombardment, and ultimately forced displacement. It is worth noting, however, that nearly twice as many people live in the eastern Ghouta as were still in Aleppo at the end of 2016—this makes the dimensions of the present catastrophe that much more significant. Furthermore, it is not clear where people displaced from the eastern Ghouta are supposed to go. Even Idlib province, which has become a giant open-air prison for displaced and oppositional Syrians, is regularly bombed by the Russian air force.

The significance of the eastern Ghouta is also due to its geographical proximity to the capital Damascus, which is still firmly in the hands of the Assad regime. The military campaign against the eastern Ghouta aims to expand and secure the regime’s area of influence to include strategically important locations. As Assad’s forces as well as foreign militias loyal to the regime attempt to split Ghouta into separate pockets in order to cut off all routes of supply, the so-called international community is reacting with helplessness at best—but is mostly simply looking away. Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein, the current UN high commissioner for human rights, has declared that the Syrian regime is planning an “apocalypse” in the eastern Ghouta. No actions have followed these dramatic words. The UN has not only proved itself incapable of stopping the murder in the eastern Ghouta, but has not found it possible to conduct regular aid deliveries to the area or prevent the confiscation of medical supplies by the regime.

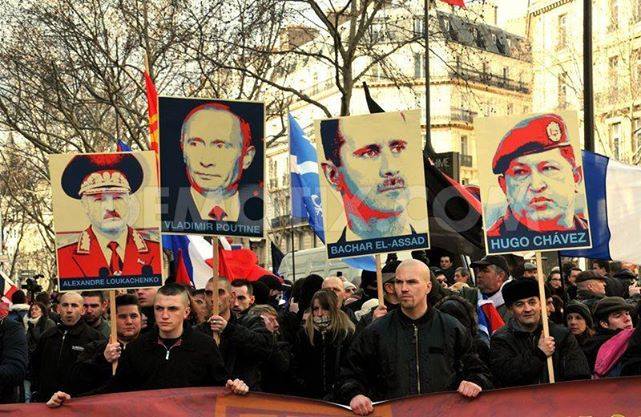

Europe—in any case more of an ideological construct than a political reality—doesn’t have much to win in Syria. French president Emmanuel Macron has threatened to carry out military strikes against the Assad regime if it uses chemical weapons against civilians, but immediately added, incorrectly, that there has not been proof of such attacks. Germany, the EU’s leading power, receives a third of its gas and oil through Russian deliveries; no serious positioning against the Putin regime is to be expected from them either.

Much more pressing is the question of whether the “America First” policies of the Trump regime will in fact lead Germany and other European countries towards even closer ties with Russia. The US’s interest in Syria appears to be above all to establish a more or less enduring presence in the northeast of the country, where there are more extensive oil and gas resources—this was likely the main reason for the US air force’s early February attack on Assad troops and Russian mercenaries when they assaulted a position of the US-allied Syrian Democratic Forces in the Deir ez-Zor region.

The measures to be taken now are obvious: an immediate ceasefire, the immediate lifting of all sieges and immediate access of aid organizations, the release of all political prisoners, and immediate protection for all people in Syria. These demands have been made again and again, most recently in an open letter initiated by the Syrian writer Yassin al Haj Saleh and signed by over three hundred intellectuals, scholars, and activists. The implementation of these measures would admittedly require a forceful approach, to which no international actor is apparently prepared to commit. The price of inaction will continue to be paid by the people of the eastern Ghouta and Syrians everywhere.

Translated by Antidote and published with permission of the author