Transcribed from episode #8 (“The Gaza Strip Today & Battle for Survival”) of Irrelevant Arabs and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole conversation:

Now that the reactionary ways of understanding ourselves and thinking about the world are in decline, there is a huge opening for us progressive Arab youth from this region to further these struggles.

Mustafa: Today we are continuing our Palestine conversation, starting off with Murtaza Hussain asking Jehad and Mariam a question. Murtaza is a journalist from the Intercept who writes about the US war on terror.

Then we’re going to segue into a more in-depth conversation about the micropolitics of Palestine and the current situation in Gaza.

Murtaza Hussain: I had a question, Mariam and Jehad, about what you think will happen in the future.

As you know, it’s a universal dynamic when there’s a conflict: the victors tend to write the history. We see this in the aftermath of the revolutions; they are being redefined as a battle against terrorism. “There may have been some excesses, but we had to deal with the jihadists,” and so on. This language is very compelling to a lot of people in the international community because it suits their framework. We also see journalists who are going to the regimes. They take these trips, very tailored visits, and then produce a narrative that fulfills that story as well.

So my question is: when you have a setback, when you have a military defeat or the suppression of an uprising, how do you prevent the victors’ history from becoming the narrative of the period? And if there’s a continuing revolution, or a future revolution years from now by another generation, what is the story of this period that people can look to that will unite them as a sense of inspiration for fighting for emancipation in the future, to complete what was begun in 2011?

Mariam Barghouti: I have an issue with the focus on drawing legitimacy from how we are portrayed to the West, because there is a whole hierarchical power of control. I always have an issue with that being our focus. We draw validation from that. Even in Palestinian rhetoric, we always bring up the UN. It’s sad that we need this validation instead of just struggling.

To avoid that, if we just continue the struggle on the ground, we will de facto shift the entire narrative. Whether it’s an accidental shift or not, it’ll happen without us really focusing on it, just by struggling and by pushing our own choices and actions, without drawing validation from these external powers who don’t have to suffer the consequences of whatever happens.

We survive. Despite it all, we keep going. The fact that we’re still talking is important. The fact that there are those of us who still believe in each other, believe in the righteousness and the right to live with dignity—on its own, that is a story that is going to be told for years.

M: From the continuing experience of Syria and most of the Arab world, I think if I were a grandfather somewhere sitting back one day and telling the next generation what to look for, I’d simply say, “If there were a side that is throwing rocks, and the other one is rolling in with tanks, it wouldn’t take me two minutes to figure out which side I’m on.” There are people all around the world struggling against very violent dictatorships. It’s really clear on whose side we should be. Even in the beginning of the Syrian revolution, when ISIS was becoming a thing, and Jabhat al Nusra was becoming a thing, they were obviously better equipped than the Free Syrian Army at that time.

I have a more pessimistic note than yours, Mariam, because yes, while we have survived…well, we can say that, but unfortunately many can’t. We started off with Palestine, the country that we lost, and then we lost everything. We lost Syria. Lebanon’s pretty fucked up. Iraq is fucked. And Yemen, and everywhere. So it’s getting worse.

Malek Rasamny: We tend to think about class issues as being static. Just, “it’s bad.” No, it’s bad and it’s always active. Oppression is active. Oppression is volatile. Oppression radiates. It’s not simply a static being. It’s not just that Gaza is under siege. It is continuously under siege, but that means the situation is getting worse by the day. And as something gets worse, there’s potential for activation.

People didn’t get this about the Arab Spring. The attitude seemed to be, “It’s just unjust. It’s just like that.” And then you get the whole orientalist, racist bull: “Oh, it’s been like that for thousands of years.”

Jehad Abu Saleem: Young people were living that rebellion but were unable to make sense of that moment. There were the beginnings of social media: Arab citizens were reading things and saying things away from censorship, away from the state narrative, and away from the ministry of information and the mukhabarat. This was new. This was unprecedented. This was a moment where people realized how powerful they are.

Once they got an opportunity, a chance to connect and to build these movements, that—regardless of their outcome—proved that Arabs’ imagination actually started working. All of us heard these lines when we were kids: subjugation to despotism is in Arabs’ blood; they will never rise against dictators; only a just dictator can rule the Arab world. By the way, this was coming from many secularist and leftist Arabs; we were being shamed. After ’67 and other defeats, they were shaming Arabs for being backwards, for being primitive. This is a self-hating, internalized-orientalism way of thinking. Everybody starts talking about the Arab mind. What’s wrong with the Arab mind? The Arab mind is not rebellious; the Arab mind likes despotism; it’s in their blood; it’s in their genes.

And then comes 2011, and it confuses the shit out of everybody. Honestly, no one was prepared. So here’s what I think. It’s important for us to start working on intellectual projects through which we can make sense of our region, connect our histories, connect our struggles, and connect all these different fronts for liberation. Because unlike any other place on Earth, we’re facing many, many enemies with a really sophisticated mix of players who share one interest: they don’t want our people to claim their independence and gain access to ruling ourselves independently of these forces. They use sectarianism against us. They intensify these things that are supposed to divide us—sect, ethnicity, language, race—and they use all these things to turn our part of the world into spheres of influence where they can play us like chess.

So again, our generation needs to not be pessimistic, needs to not lose hope. What we witnessed was just the beginning of something. Of course we will still live the consequences of the setback of the uprisings. But now that the Islamist imagination was put to the test, and all this Islamist rambling about the arrival of the Messianic Age of Glory turned out to be nothing. It turned out to be mumbo jumbo (that never justifies crackdowns on and oppression of Islamists, and of course we condemn the groups that hijacked the revolutions and committed horrific acts of violence. This is something we agree on, in principle). So now that the Islamic imagination is out of the equation (hopefully), and now that these reactionary ways of understanding ourselves and thinking about the world are in decline, there is a huge opening for us progressive Arab youth from this region who want to further these struggles.

In Gaza, people welcomed the Egyptian and Tunisian uprisings. I grew up in a place where teachers and elders ranted not only about how bad the occupation is, but also about how bad the Arab regimes are. We were pretty passionate about that moment. We were very excited. We saw Mubarak as complicit in the siege on Gaza.

We need to connect, we need to learn from each other, and learn about the histories of struggles in different places, and get together and build a larger thing together, so that when there is another revolutionary wave, we can be more prepared to have a lexicon, to have the language, to have the framework and the worldview to make it universal, to make it everybody’s.

MR: Mariam grew up in the West Bank, and Jehad grew up in Gaza. So maybe you guys can talk a little bit about the reception of the Arab Spring in Palestine, and then segue from that into a larger discussion of the specific, because that’s what gets lost. In Syria, we see the complete erasure of micropolitics. It’s just big chess players. So maybe through the Arab Spring we can talk about the particularities of the political situation, both in the West Bank and in Gaza as well.

JA: In order to talk about the reception in Palestine of the Arab uprisings, and the Syrian uprising in particular, we need a short background on the Palestinian political and ideological scene today.

Basically, if we want to have a qualitative division of Palestinians according to their political subscriptions and ideological beliefs today—here I can generalize. But you should keep in mind that sometimes the boundaries between these categories can be blurry; they are not black and white. But they are useful to us to make sense of who is there.

Palestinians in general dwell in the following categories: there are the Islamists/pan-Islamists like Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Then (and I know this has become a derogatory term) the Salafists in Palestine are also two groups. There is the Tawhid, and the other group that does not believe in dawah and believes in armed struggle—

MR: What’s dawah?

JA: Preaching. They don’t believe in jihad at the current moment. They think that jihad is tied to having a Muslim ruler. Anyway, the Salafists are very marginal, small groups. Generally, Hamas is the hegemonic group in the Islamist part of Palestinian politics. There is a wide range of ideas about Islam and about how to resist the occupation; about relationships with other Palestinians, with other Arabs, and with and the rest of the world.

For example, the Islamic resistance movement Hamas is considered the spearhead of Palestinian armed resistance against Israeli occupation, yet it’s not 100% socially progressive, and this is something about the complexity of the Palestinian political and ideological scene. There can be a group that is politically radical in its resistance against the occupation, but it might not be socially progressive.

Another group is the nationalists/secularist-nationalists. This group includes Fatah (the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, headed by Abbas), which is also divided into different subgroups—and there are different people who do different things in Fatah itself.

And camp number three, which is relatively marginal compared to both Islamists and nationalists, is the left. Mainly, when we talk about the Palestinian left, we talk about the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and other small groups.

Because you asked me about the responses to the Arab Spring from the Gaza corner of Palestine: people welcomed the Egyptian and Tunisian uprisings. I grew up in a place where our teachers and elders ranted not only about how bad the occupation is, but also about how bad the Arab regimes are. We were pretty passionate about that moment. We were very excited. We saw Mubarak as complicit in the siege on Gaza, and as someone who did not carry himself as a leader who deserves to be head of a country like Egypt. Then of course, Tunis was the inspiration. People really loved this moment.

Now comes Syria. Syria was the moment where things got really complicated, for many reasons: reasons that had to do with internal Palestinian politics themselves, and reasons that had to do with the levels of uncertainty accompanying the Arab Spring when the situation in Syria started to deteriorate. But because Hamas is the party that rules Gaza, and because it has a very large social base, it’s really important for me to highlight how Hamas responded to the Syrian uprising. Hamas welcomed the Syrian uprising. They were really excited. Especially the base.

But at the beginning of the Syrian uprising, most of the Hamas political bureau was based in Damascus. And although Hamas was committed to a policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of Arab countries, it found itself under both Syrian popular pressure and regime pressure as well—and they were supposed to take sides, from the very beginning. They found themselves in a very complicated situation. In the first two months of the Syrian uprising, Khaled Mashal, the former chief of the Hamas political bureau, put a massive effort into reconciling both sides so that a process of change and reform and national agreement in Syria would be achieved away from foreign intervention. This was the original position of Hamas.

But the gap between the regime and the opposition and the Syrian masses got wider, and the regime refused any kind of reform. This made reconciliation hard. So by April 2011, Hamas was under enormous pressure to explain its stance. Hamas was silent. Its media platforms were silent. We’re talking about April 2011, a few weeks after the beginning of the Syrian uprising. People are watching on television and social media, and they see the brutal suppression of the civilian uprisings, and the social base of Hamas—the membership, the people who are the incubator of this large Palestinian faction—was boiling.

At this point, Hamas was risking falling apart. What happened? Hamas leaves Damascus. But the exodus of the Hamas leadership from Damascus happened gradually and slowly, so as not to antagonize the Syrian regime or Hezbollah and Iran. What was ironic about this moment was that the Syrian regime, Hezbollah, and Iran were expecting Hamas to take sides with the regime of Bashar al Assad—against its own political interests and considerations. People on the Palestinian left sometimes view Hamas’s decision to leave Syria as opportunistic, but they don’t really consider that real demand to take sides with Bashar al Assad, which for Hamas was politically and morally impossible at the time, because allies were almost to power in Egypt, and there was this larger moment of change where Arab Islamists started seeing themselves as the main vehicle of the moment.

There is a naive idea that Palestinian political factions represent some kind of ideology or agenda, when oftentimes they are really just different vocabularies created around what are essentially patronage machines.

With zero appreciation for these considerations, the Assad regime and Iran demanded Hamas take sides with them, and they made their support of Hamas conditional on these terms. But regardless of the situation, Hamas left Damascus, and the leadership started to move slowly to Gaza, where the leadership was unconditionally in favor of the uprising in Syria. Of course, they were comfortable with the scenario of the fall of the regime of Bashar al Assad in favor of a democratic process in Syria that would bring the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood to power there.

If you think about it, if you are seeking an alliance in a place like Syria, then you might as well have a government that represents the majority there, that can support you. In fact, the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood at the time stated that in a scenario of their getting to power, Hamas would be welcomed again; the Palestinian resistance would be welcome again in Syria with less condescension and fewer conditions than the ones the Syrian regime was requiring of Hamas.

So this sums up the Gaza dimension of how the Palestinians received the Arab Spring, mainly around Hamas because it’s the major force in Gaza. That said, although Hamas had this position, as part of how political positions are shaped across factionalism, there were Fatah people—whose Palestinian Authority does security coordination and has peace accords with the Israelis—siding with Assad just because the Palestinian Islamists were excited about the Syrian uprising. This is ironic and very interesting.

MB: With all these leaderships, it just became this proving of presence and authority; no one really approached the uprisings in the Arab world or Syria with the nuance that it needed. It was very self-centered, and it was reflected also on the ground beyond Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, among people themselves as well. They looked at how the fall of the Assad regime or the maintenance of the Assad regime would affect them, without realizing that if a despotic regime remains, it’s going to negatively affect their cause.

In the West Bank, in 2011 when everything started, there was also support for the Syrian uprising. We used the chants. There were solidarity statements coming out. Gradually that started to become more cynical and skeptical in Palestinian circles. But especially with the factionalism that was there, there were people with the PFLP who were very pro-Assad, while since Hamas supported the uprisings, the Palestinian Authority and Fatah wouldn’t.

JA: As for the Palestinian left itself—there is a crisis of imagination here in the West. Palestinians subscribe to their line of thinking here in the US; leftists more broadly view the PFLP as the leftist presence in Palestine who you go to for nuanced analysis and positioning. There is a disconnect. The PFLP itself has a generational crisis. There are a lot of elders in leadership positions, and not all of the younger generation support Assad. They have really bright writers who did not side with Assad, and criticize the PFLP for taking that position.

Sometimes with Palestinian factions, what determines the outcome of these alignments is not necessarily analysis or an ideological position but rather how they view their interests in the short term, and because Palestinians are running all these massive structures and bureaucracies called factions, they need money to operate these things. They need aid and support. So when Hamas left Syria, it was an opening for the Palestinian left—which by the way was not always on good terms with the Assad regime—to find support and backing by Iran and by the Hezbollah-Assad bloc. Traditional leadership of the Palestinian left—which is out of touch and has a really terrible analysis of the situation—found in Syria a place where they could continue getting backing and support; they saw that opportunity when Hamas left and ceased to be the Syrian regime’s major ally in the Palestinian political scene.

So there is an element of factional alignments that happened in light of the larger geopolitical scene.

MB: Palestine basically just followed the rest of the world with Syria, making it this playground of forming and breaking alliances. That’s what made this entire rift among people over Syria: not seeing it for what it was during the uprising, not seeing the demands of the people.

JA: The moment when Islamists began to claim the moment of the uprisings was not a pleasant moment in the history of these uprisings. Again, violent crackdowns by Arab regimes against Islamist groups, parties, movements, and their followers are never justified. But also, Islamists themselves saw the uprisings as an opportunity for them to get to power; they were not considerate of opposing parties, and they contributed to this situation.

Again, there is a long reading that we need to do of that history. Yeah, Palestine was shaped by these events and factional alignments, and Palestine of course still continues to shape these alignments. As a Palestinian, I really hope that we at some point can finally operate independently of these regional and international backers and supporters. We have been paying a heavy price. We have been making our positions, our analysis, and sometimes our moral commitments conditioned on the support of these forces that see in Palestinians a certain leverage rather than a need for support in order to further their struggle. That’s the problem.

MR: A lot of what you’re saying rings true. I did some work in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, and they also outline their issues as issues first: of course, Israel kicked them out and prevents them from going home. But then the Lebanese state also denies them their rights, and then the factions deny them their right to take hold of their destiny within the camp, let alone within the Lebanese state. They defined this, like Ghassan Kanafani, as three layers of struggle, with the factional layer being the closest, then the Lebanese state, and then finally Israel, in terms of proximity.

Another thing that I find interesting is the idea of factions being just job-creation machines, which was also something that was echoed when I went to Lebanon. There is a naive idea that these factions represent some kind of ideology or agenda, when oftentimes they are really just different vocabularies created around what are essentially patronage machines.

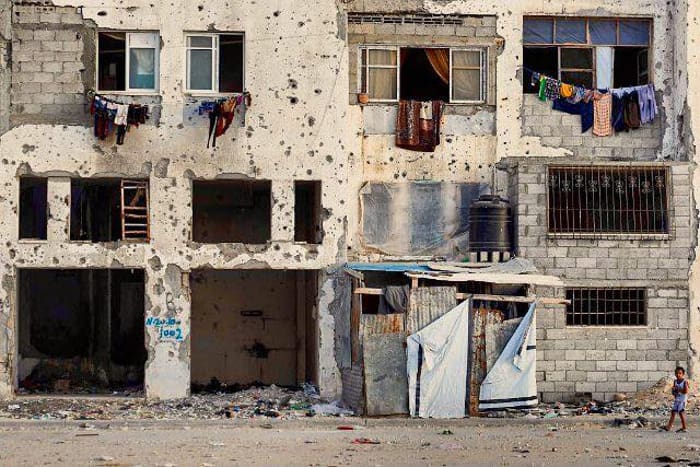

What exactly do you mean by the idea that Gaza is collapsing? How is it collapsing, and what does that look like in detail?

Gaza is a Palestinian city. Israel has taken this city and turned it into a prison, which is part of a larger prison—the Palestinian prison. Yes, we will criticize Hamas, it’s very problematic, but it’s also a symbol of a form of Palestinian resistance and defiance, as is the entire strip itself.

JA: While I’m talking to you right now, the strip is undergoing an unprecedented deterioration—on the social, economic, and really every conceivable level. The basic necessities to maintain people’s lives are at risk. This is of course the logical conclusion of eleven years of isolation, eleven years of total blockade—which, by the way was only eased during the Morsi administration in Egypt (just to be fair to history).

The situation is really dire. People are homeless on the streets, sleeping in the cold. The situation is really terrible. Forty percent of necessary basic medicine in hospitals is about to run out. Unemployment among youth is sixty to eighty percent. General unemployment is fifty percent. Water is polluted. People are unable to travel. Patients are unable to access medical treatment. It’s been eleven years of that, and at this point people in Gaza are really desperate for something, and even Israeli media and Israeli military leadership has been warning about an imminent deterioration on the Gaza front. They are expecting that there will be military confrontation, but the general public in Gaza is not interested in a military confrontation.

At the same time, there is energy brewing in the darkness of the electricity-deprived, water-deprived, nutrition-deprived, medicine-deprived Gaza strip, and people are really fed up. We’re hearing unprecedented stories of people setting themselves on fire. Young, bright, polished graduate students—young men who just finished school, setting themselves on fire, killing themselves. Drug addiction, crime, divorce. All these sorts of things are happening in Gaza right now, and it’s a really miserable situation.

Again, if it weren’t for this moment where there is an Arab-Israeli alignment against this place (for many reasons), Gaza stands for revolution, for rebellion, for defiance. But also, Gaza is being punished because of Hamas. Hamas is considered now by many Arab states (in addition to Israel) to be a threat. Hamas is the jewel in the crown of the Muslim Brotherhood—and again, we disagree with Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood on many issues, but it’s the spearhead of Palestinian resistance at this point, as considered by many, and Gazans are being collectively punished for that. And what the international community is demanding from Hamas is political suicide. The price is going to be nothing. There is nothing offered in return.

Israel has been managing the status quo with no grand plan on what to do with Gaza. They have a few theories; they were expecting that by having the siege imposed, people in Gaza would rise against Hamas and kick them out. But we all know that Hamas is a product of the Gaza reality, and it’s part of the Gaza experience. There is this strip of land inhabited by refugees displaced from their homes and villages in 1948, who continue to live under the continuous misery of occupation for almost seventy years.

But as you know, Israel uses “war on terror” discourse to demonize Gazans, to portray Gazans as monsters, to justify counting calories and putting people under siege just because they made what Israel views as the wrong political choice with Hamas, which represents all other forms of resistance. So I’m urging the audience to read more about the situation in Gaza, to follow people from there who are reporting on the the current situation, to talk more about Gaza in their circles and on social media, and to raise awareness. There might be another war soon—or there are other scenarios, but no one knows exactly what the next weeks are hiding for us with regards to Gaza.

What we know for sure is that the situation is dire, it’s miserable, it’s falling apart, and unfortunately no one is doing anything to stop this madness.

MB: When we speak about Gaza, we always forget that it’s a Palestinian city. They have taken this city and turned it into a prison which is part of a larger prison—the Palestinian prison. Yes, we will criticize Hamas, it’s very problematic, but it’s also a symbol of a form of Palestinian resistance and defiance, as is the entire strip. This entire punishment, the slow asphyxiation of Gaza, punishing civilians as a way to bring them down and break them, is an Israeli strategy to set an example. They can’t bomb the West Bank. Forty-two percent of the West Bank has settlements. They’re not going to bomb the entirety of the West Bank. Gaza, on the other hand, is all Palestinians, so they can bomb it all they want.

It’s setting the example for the entire Palestinian community that if you ever think of defiance, if you do ever think of resistance, in whatever form or manifestation, the end result is going to be: you’re going to be called a terrorist and vilified, and you’re going to suffer the consequences of not being treated like a normal human being. The Palestinian Authority is also complicit in the electricity cuts in Gaza. There’s supposed to be a reconciliation bill for the hundredth time in the last five years—that went nowhere.

I think Gaza is such an important part of Palestine because it resembles defiance, it resembles resistance—but it also resembles the ugliest face of the occupation, the colonialism on the entirety of the Palestinian people. It’s very important to focus on Gaza right now and all the nuances that come with it as well. Most of Gaza are refugees. Eighty percent. The symbol of the refugee—fifty percent of the Palestinian population does not live in Palestine—is a huge factor in breaking their wanting to return, breaking the idea that despite being displaced from your home you still consider yourself Palestinian. All of this is in Gaza. It’s so important to help save it. It’s taking what essentially are its final breaths.

MR: Any final words? Not to sound too morbid.

JA: Thank you for having us. I hope for more conversations.

M: Thank you everyone for listening.

Featured image source: Gaza Youth Breaks Out (Facebook)