Wait.

by Chris Jones for Samos Chronicles

29 March 2018 (original post)

“I hate this word. I have come to really hate this word. Because it is killing me.”

Assad, a 23-year-old from Syria, speaks for the overwhelming majority of refugees in Greece. Sometimes we are not careful in our choice of words. But if we to listen to the words of thousands of refugees stuck in Greece, then we need to recognize that the endless waiting endured by the refugees demands to be described accurately: it is a cruel form of torture.

There are many casualties. Our friend from Morocco, for example, who lived with us for four months, has been driven crazy. He stripped off all his clothes and ran round the central square in Samos town waving his arms like a bird. He is now in a psychiatric hospital. Then there are our friends from Syria who went back to Turkey in utter frustration at the delays and waiting—over fourteen months—on Samos, only to find themselves in a worse position. Their close and loving relationship has fractured under the pressure. Their current plight is dire.

We have a Somalian friend who fled from a violent relationship in Turkey, leaving behind her four-year-old son. That was two years ago. She told the authorities her story and how important it was to get her son from the father, who does not now want him. Her son is now six and still in Turkey. Our friend does not even have a date for an asylum interview. Whenever she asks, she is told, “No news. You must wait.”

Ahmad’s long-standing partner could not cope with waiting in Athens, and after sixteen months set off on his own to find a way into northern Europe. He is now stuck in the central Balkans, alone and depressed. Ahmad, on the other hand, similarly depressed by not being with his love, waits—only to find out last week that his asylum interview will be in June 2019, and this is being fast-tracked so he should count himself lucky!

Your life, in many respects, stops. You lose control over key areas of your life. You can’t plan. One friend from Syria managed to secure a scholarship, worth $30,000 a year for three years, to study in the USA. He has lost it to the wait and no decision. A few, like Ahmad, have a date fixed, but the majority don’t even have an appointment. So they wait. There is no warning when a decision on asylum or detention on the island will be reached. There is a continual uncertainty. You hope, you despair, you go from moment to moment. Maybe tomorrow…

Many turn in on themselves. You quickly get to know those who get decisions, and hear how long they have been here. You wonder why some get quick decisions and you have not. Is there a problem? Have I done something wrong? It is an environment that generates gossip and innuendo. Waiting in the dark like this corrodes well-being. It is cruel.

And there is no light on the horizon. Hoped-for destination countries such as Germany are deliberately slowing down their refugee policies including family re-unification and relocation. There is no mystery as to motive. The waiting has become an embedded aspect of Europe’s deterrence approach. There may be little evidence to show it actually deters arrivals, but there is growing evidence that it does encourage refugees to give up their European dream and return to their countries, especially when a small financial inducement is included.

The Greek frontier islands such as Samos have become prison islands for the refugees. Most are here for months, and many for over a year. And it goes on. All of the mayors on these islands are unhappy, and resist becoming places of indefinite detention, consistently refusing the central government’s demands that they develop their facilities. Maybe these mayors will succeed, but the outline of the intended policy becomes ever clearer. Refugees are increasingly going to be kept in Greece even if not on the islands. The EU and its constituent members, albeit unevenly, are all moving in this direction. Hold the refugees in Greece: here and no further except for a tiny number.

But in these fields of grief there are many miracles that often go unnoticed. Despite the wait, the overwhelming majority of the refugees continue to endure and do not collapse in the face of such cruelty. They surely suffer, but they also resist. Friendship networks play a huge role in keeping people sane. We have spent hours in friends’ rooms drinking tea and talking and talking. Shisha helps too and if you have a good pipe you will never be short of friends. Laughing, playing and talking together, with children, family and friends is critical. And, not least, these friends can be a source of walking companions. When you have no money you tend to walk a lot. When your accommodation is uncomfortable you walk even more! Many of our friends talk about walking as a way of relaxation. Certainly it can help you sleep and nothing is better at eating away the hours than sleep. And for those fleeing war there is the relief to walk without fear.

The most cursory glance at the many survival strategies operating could not ignore the role of the ubiquitous smart phones. These devices are of massive value not only for keeping in contact with distant friends and families and your home country but also for passing the time, watching movies, playing games, flirting, and choosing images for your profile picture—these seem to change regularly and often reflect the person’s current mood.

All the refugees we know have no money other than the small monthly allowance they receive from UNHCR. For single people in the camp this is around 90 euros a month; slightly higher for families. If housed outside the camp, which is the case for many in Athens, then the sum is 150 euros a month. From this you are expected to feed yourself. In Greece, you always know when you are in an area with a lot of refugees because of the presence of money exchange offices, especially Western Union and MoneyGram. These companies make money off of refugees. But without the remittances sent by (usually hard-pressed) relatives and friends, many would be utterly destitute and hungry.

Their poverty means that their survival strategies are without significant costs, hence the walking, visiting friends, and sleeping. On Samos, there is also the fishing, and in the summer, swimming. The weather plays a big part, and the winter months are much harder to endure if the weather is bad. The desperate poverty of some push them towards much more ambiguous and often hazardous behaviors including petty crime and what has come to be called ‘survival sex’ involving both boys/men and girls/women. That there are so many Greeks willing to take advantage of these vulnerabilities says much about Greek society, but that is another story.

The survival strategies are many and varied, and stretch across a wide range of activities. Many pass up and down this range depending on their circumstances and mood. Forged out of necessity and a long way from what might be considered normal everyday activities, the majority of refugees avoid both the psychiatric ward and the hell of drug and alcohol addictions. They are never unscathed but neither are they defeated.

These miracles can never be taken for granted. As the wait gets ever longer, as they never get any information about their own applications nor about the context generally, the stress levels will inevitably build. Refugees see the hundreds of people who work in the Samos camp and the long line of their vehicles stretching along the lane which leads to the gate. Quite understandably, they ask, What are all they doing? Why, with so many people, are we watching months turn into years? No answers. Never any answer other than: Wait.

It takes no sharp intelligence to predict that we are going to see increases in suicides, self-harm, anger, frustration. Many feel that the big question now is not if the camps will blow up but when. Still, we have learned never to underestimate the capacities and intelligence of the refugees. And we also know that the violence of the state should not be underestimated. As the camps simmer, the authorities and frontline agencies continue to dig in. We have a lot more police in Samos town now, with more gear, buses, and paramilitary-style vehicles. The agencies in the camp have now put fences around their offices, with guarded gates. Employees of the notorious GS4 “security” company now stand guard at these gates. Without an appointment you won’t get in. All these smaller compounds are already within the fenced and guarded camp! It is a prison, with prison design and prison regulations. But it is refugees who live here, not criminals. And what frightens some of us now is that the endless feeding of negative stereotypes about refugees is creating the kind of hostile atmosphere which would tolerate violent repression if the camps did ever truly explode. The many children in the camp will not offer any protection should this happen.

It is of critical importance that the human beings currently detained on the islands and on the Greek mainland not be forgotten. If they are forgotten and pushed into the background as a regrettable footnote, so the darkness will deepen—which in turn will open the doors for greater violence and cruelty. The refugees here confront power far greater than themselves. Until and unless there is a massive public outcry at these cruelties, the nightmare will continue.

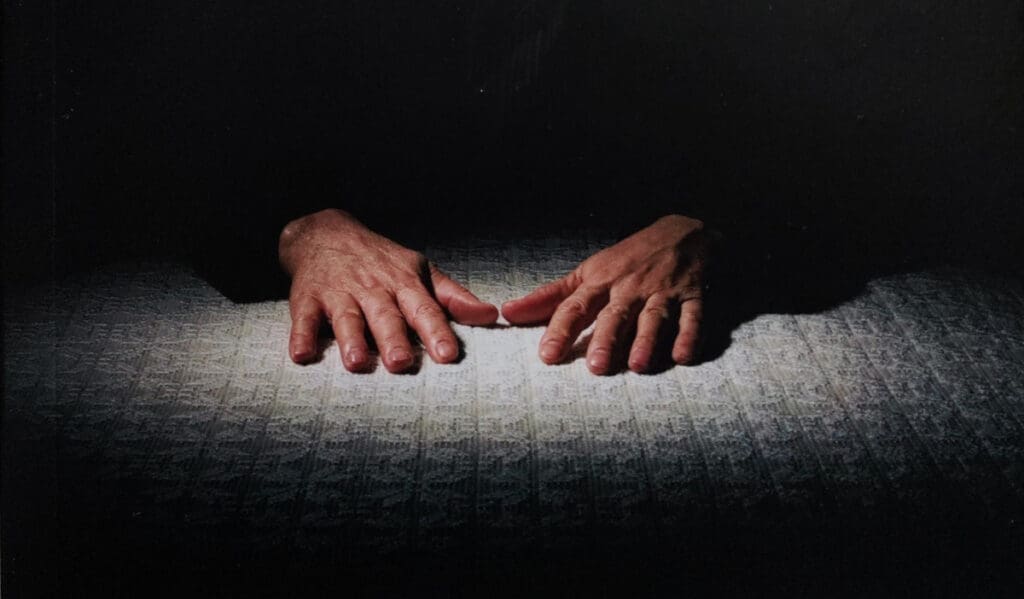

Featured Image: “Resting at Karlovassi Port,” August 2015. Source: Samos Chronicles