The Struggle of Women Across the Sea

by the Alarm Phone network

22 March 2018 (original post)

Silvie and Joelle

In April 2017, Sylvie and Joelle wanted to cross the sea to escape their predicament and start a new life in Europe.i They did not know one another until they boarded the small rubber boat in Turkey, together with twenty-two others, including two children. Sylvie was anxious and entered last, handing over her red bag to Joelle who promised to return it after their safe arrival. They departed, but at some point, somewhere in the Aegean Sea, they ran out of fuel and could not continue. Sylvie tried to call for help, but her phone was caught by a large wave. Lost at sea, Joelle, who was in the eighth month of pregnancy, started to cry and pray for help, but nobody came. The boat capsized, and everybody fell into the water, drifting away from each other.

Sylvie and Joelle were separated, but Joelle did not give up. “I had a strong feeling of power in me. I don’t even know where this came from. Where we fell in the sea there was nothing: no boats, no fishermen, no police, no one.” She was able to stay together with two others, Guilaine and Teddy. They floated in the water throughout the night, trying to stay conscious and together. But at some point, a wave parted them, and Joelle was all alone. Hours later, she suddenly saw a boat approaching. She was taken aboard the rescue vessel of the NGO ProActiva and brought to land.

Sylvie was able to stay together with three others as well, holding hands, talking, giving each other hope, and trying to stay awake. But after a while they also lost one another, and when Sylvie was finally discovered, she could not see anymore. “The sea salt had burned my eyes. I was blind.” She was brought to Joelle and together they went to the hospital. Joelle wondered: “Where are the others? Let’s hope they bring them even if they are not alive. But no one could join us. The same evening I saw an assistant and a psychologist and I asked them: ‘Where are my brothers and sisters?’”

Eventually, they were informed that only the two of them had survived. Two out of a group of twenty-two. Joelle still had the red bag with her, and returned it to Sylvie. “I thought maybe she has her money inside, I can’t abandon the bag.” Joelle said that without the search-and-rescue NGO, they would not have survived. She gave birth a few weeks later to a healthy girl. “She is my joy and my power. I believe I would have died if she was not in me. God really pitied me. It’s really a miracle. I call her Victoria-Miracle.”

Intersectional Struggle

Stories of women struggling across sea borders are rarely heard. When we do hear them, women are often simply portrayed as subordinate, exploited, and passive victims who depend on male companions, and who lack individual migration projects and political agency. The erasure of their agency and voices is also the effect of hegemonic narratives of migration to Europe, in which ‘the migrant’ is routinely imagined as young, able-bodied, and male, more an abstract figure than a human being, commonly constructed as a dangerous subject against whom border enforcement and deterrence policies are legitimized.

Knowing well that the personal is political, and the political is personal, we want to listen to women’s voices and stories, and be inspired by their disobedient movements, their strength, their resistance. This report is being published shortly after International Women’s Day, on which women led demonstrations all over the world, including in Spain where the first nationwide ‘feminist strike’ took place against sexual discrimination, domestic violence, and the wage gap; or in Turkey where the crowd of protesters shouted: “We won’t shut up, we aren’t afraid, we won’t obey”.

The European border regime is also a gendered regime. It creates hierarchies of mobility, making it impossible for many women to leave their places of predicament in the first place. If they are able to leave, they have particularly gendered experiences, and unfortunately, many are exposed to systemic forms of gender-based violence. The increasing securitization of borders and the criminalization of migration are the main factors contributing to ever more risky journeys, and the need to find professional help in overcoming border obstacles. Given the ever lengthier and costlier journeys, exploitative situations are common, and ‘consensual’ movement can quickly turn into ‘non-consensual,’ or forced, movement. At the same time, the dominant binary understanding of ‘voluntary’ or ‘forced’ migration, even inscribed in international refugee conventions, cannot do justice to the complexity of migrant experiences and journeys, and certainly not to their gendered dimension.

When women cross the sea, they often have different experiences than men and are exposed to greater danger, due to a range of factors. Proportionally, more women than men drown when trying to cross a body of water. In the central Mediterranean, they are often seated in the middle of rubber boats, intended to keep them as far as possible from the water and thereby ‘safe.’ However, it is in the middle of the boats where sea water and fuel gather the most, creating a toxic mixture that burns their skin and often causes grave injuries. There they are also most at risk of being trampled and suffocated if panic breaks out on board. In some of the larger wooden boats, women often sit in the vessel’s hold, where suffocation due to the accumulation of dangerous fumes occurs more quickly, and where, in situations of capsizing, escape is more difficult. Many women wear longer and heavier clothes than men, making it more difficult to stay above water when they have fallen into the sea, and it has been reported that women leaving from Libya often have insufficient swimming skills. Some women are pregnant, which increases the risk of dehydration, or they hold the responsibility to care for young children who travel with them. And, of course, they are also exposed to patriarchal forms of violence, during their entire journeys, including on the boats.

The Shifting Gender Composition of Migration

In the first weeks of 2018, up until mid-March, women composed about thirteen percent of travelers through the Mediterranean Sea. In the Aegean Sea, we see the most diverse composition of groups in terms of gender, with women making up twenty-two percent of those crossing to Greece (and also in terms of age, with children making up thirty-seven percent here). In the central Mediterranean, the number is about half that, women making up about eleven percent (with around fifteen percent children). In the western Mediterranean, we have the lowest number of women crossing, with about eight percent women (and thirteen percent children).

While the Harraga border-crossers from Tunisia are still predominantly male, we saw more young women take to the boats over the second half of 2017 than ever before. Given the lack of data, we cannot say how many of the 458 deaths at sea so far this year were women.

Throughout their entire migratory trajectories, women are affected disproportionately by violence. Especially the women we have spoken to who fled from Libya tell of unimaginable suffering prior to their departure. The NGO SOS Mediterranée has rescued more than four thousand women onto their rescue vessel over two years, and they report that the number of pregnant women has doubled in their second year of operation, to 10.6% in 2017. Many carry children that have resulted from rape. Given these atrocities that women are subjected to, their portrayal as victims may seem unsurprising. And yet, what tends to fall out of sight through the constant repetition of such narratives are the moments of survival, political agency, and resistance that demonstrate migrant women’s tenacity and the ways in which they transform themselves, others, and the spaces they pass through on their journeys.

In our work, we have encountered countless women who have led the struggle against borders, containment, deterrence, and the separation of families and communities. During the ‘long summer of migration’ (2015), the gender composition of travelers changed – we witnessed the feminization of migration. The reasons for the change in composition at the time were manifold, but some of the main reasons were certainly the continuously devastating situation in Syria and the escalation of conflicts in Iraq and elsewhere. Many simply could not remain in warzones any longer and had to leave, often to follow the men who had left months or years before, hoping to bring their families over once they had survived their dangerous journeys.

For many, the hope to use legal routes to travel safely to Europe – either alone or with other family members – vanished when EU member states created even more restrictions on family reunification procedures, and more and more of the few legal pathways were closed down. Moreover, for those living in exile in countries neighboring conflict-ridden places such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, living conditions deteriorated over time, and with more and more people crossing over into Europe in 2015, they also took their chances. While before there had been boats in the Aegean Sea exclusively with male travelers on board, suddenly there were boats where men were in the minority, and women as well as children in the majority.

No More Selective Solidarity

Safinaz was one of them. She called us from the sea in September 2015 and stayed in touch after she had survived the crossing into Greece, so that we could follow her movements throughout Europe, via the Balkan Route and eventually into Germany, where we met her in 2017.

She was part of the migratory movements of 2015 that would lead to a historic, if temporary, collapse of the EU border regime. Those survivors of sea crossings marched on through the Balkans, and there we saw women on the front lines—not only due to the tactical rationale that security forces may feel greater restraint to use violence against them, but also simply because they were strong and courageous, and willing to face down the European border guards who stood in their paths.

It is time to listen to the voices and stories of migrant women, who are always underrepresented and overlooked. We continue to voice our solidarity with them, with those unable to escape, those on the move, and those who, after arrival, still face extreme forms of violence, such as the over one hundred women at the Yarl’s Wood detention center in the UK who have gone on hunger strike, calling for dignified treatment and the end of detention.

Some more stories: Viviane, Samrawit, Fathiya, Nasimgul

We met Viviane in Tunis at the Alarm Phone conference ‘Mediterranean Migration Movements: Realities and Challenges’ that took place in September 2017. Viviane came from the Ivory Coast to Tunisia through some professional agents who sent her and other women into the households of wealthy people where they faced not ‘only’ exploitative working conditions but where they were also mistreated and sexually abused. Their wages were often withheld, and as ‘illegals’ in Tunis they could rarely fight openly for their rights. Often, their agents would keep their passports, so that they could not even return to their countries of origin. Many were confined in the houses where they worked and when they escaped, some sought to reach Europe via Libya. In Libya, many were sexually abused, mistreated, and raped, and even when they succeeded to get onto a boat, they were often intercepted and returned to Libya or Tunisia, where they would be kept in prisons.

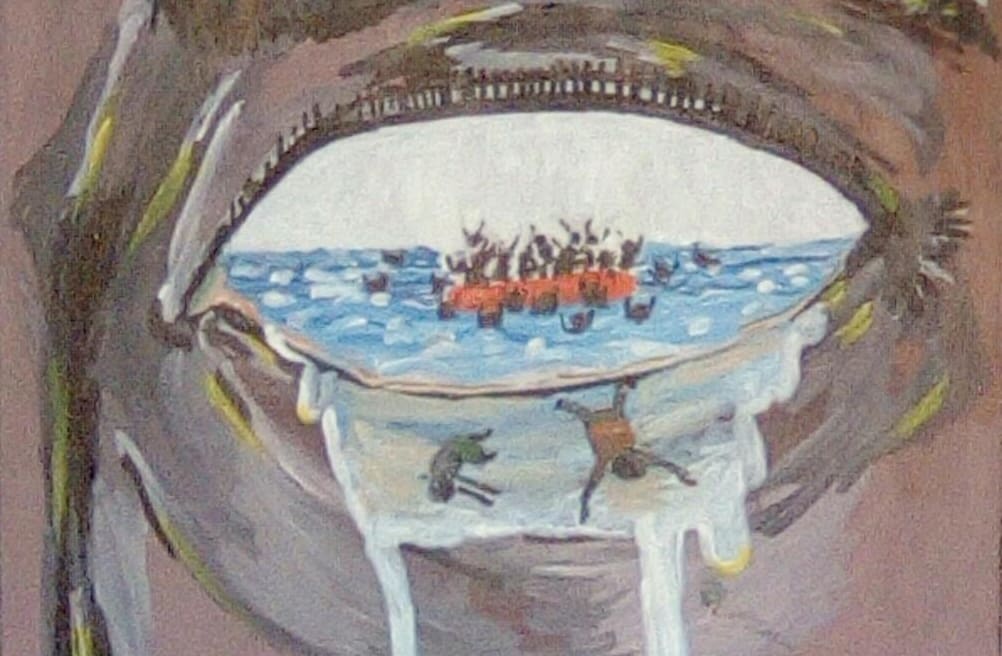

Viviane was able to escape from her employer in Tunisia. She is trained in public health and she now supports other women who have had similar experiences, giving advice and care. Because of her engagement, she faces threats from those who make money off the exploitation of women. She lives in Tunisia and has claimed asylum with the UNHCR, which was rejected, and she is thinking about going back to the Ivory Coast. Due to her insecure (legal) situation, we cannot print her full name. At our conference in September last year, Viviane told her story in front of a large audience. She showed paintings that she had made together with her brother Nali and they agreed to have them published in this report, along with their descriptions of the images. We want to thank her for that and wish her a lot of strength to continue with her struggle.

The Alarm Phone ‘Solidarity Messages for those in Transit’ video project has released several new videos, in which survivors tell their stories and give advice for those still on their way. Two of them are Samrawit from Eritrea and Fathiya, who is Somali.

Samrawit, who survived a large-scale shipwreck in May 2017 tells about her experiences at sea and gives advice also on the problem of fingerprinting on arrival. She came from Libya in May 2017 on a large three-leveled boat, carrying 903 people. They lost orientation and when they were finally discovered, the boat had fallen on its side, and many people into the water. About two hundred people lost their lives that day. When Samrawit arrived in Sicily, she was tricked into giving her fingerprints. Without shelter or support, she decided to move to Germany. There she joined the group Lampedusa in Hanau, where she collectively struggles against the Dublin deportation regime.

Fathiya was also rescued in the central Mediterranean after leaving from Libya, in March 2016. Fortunately, none of the nine hundred people on her boat lost their lives. She did not want to live in Italy but stayed in a camp for six months, where they took her fingerprints. They had to leave the camp, and without anywhere to go, they lived on the street. “It was so scary. So many people were drunk in the street, and we were afraid to live there. The women never slept, we were up day and night because we were afraid. I had a friend in another European country. She told me to go to another country in Europe to start a new life.” She went to Germany and received a rejection. But she also came to Lampedusa in Hanau and started to fight for her right to stay: “To those other people who are in a situation like me: They should not lose hope! One day we will get what we need.”

Nasimgul and her five-year-old daughter Jasna left Afghanistan because of the war. They did not plan to come to Europe but wanted to stay with her mother in Iran. But when they arrived there, they realized that the situation was as bad as in Afghanistan, so they decided to go to Europe via Turkey. They boarded a rubber boat, but it deflated, and they were just barely able to return to Turkey.

They tried again: “After half an hour in the sea, the weather got bad. Big waves came. I was sitting near the motor, holding Jasna. A wave took us. Jasna and me fell first in the sea.” They could not swim, and another wave took Jasna away from her mother. “I was crying and screaming her name: Jasna, Jasna. I heard her voice answer. I don’t know what happened then.” Nasimgul heard her cousin shout that Jasna was on the boat again, but Nasimgul could not reach the boat herself, and it disappeared.

At some point, a large boat sailed past her. In the morning, she saw another boat, and at noon, a helicopter, but nobody saw her, even when the helicopter returned in the afternoon. Her life-vest was full of water and heavy, but when she took it off, she started to drown.

Nasimgul saw some rocks. “I talked to God and said: ‘you can bring me out with the waves. Three waves and I am out.’ As soon as I said that, two waves came and threw me to the rocks. I woke up from the pain.” She climbed up the rocks and found herself on an island, and after a while, she met local residents, who helped her. She thought Jasna might have died, and when the doctor told her that she was alive, she did not believe him. “When I went in the hospital corridor and saw Jasna sitting on a chair I was so happy that I was crying.”

“I should never forget this story, I should not believe that I came out from the sea after eighteen hours in the waves, not knowing how to swim on my own. Now I am so happy. When I arrived, I met the best people in the world, I will never forget you all. I wish to arrive in a country where Jasna can go to school, and I wish to arrive in a country where we can get asylum and after that visit my mother who is so sick.”

With W2EU activists, Nasimgul went back to where she had been washed ashore. She was able to find the house of those who had helped her. The activists write: “They opened the door and could not believe their eyes! Nasimgul, the woman who came out of the sea, was standing there with her small child smiling at them. Katerina, Panagiotis and Nasimgul fell into each other’s arms.”ii

Reprinted with permission; lightly edited for clarity by Antidote

The original report includes link citations that we have not reproduced; please go there for a full list of references as well as incident summaries for each of the twenty-five distress cases the Alarm Phone network was involved in during the six-week period between 5 February and 18 March 2018.

Also, please consider donating to the network via PayPal.

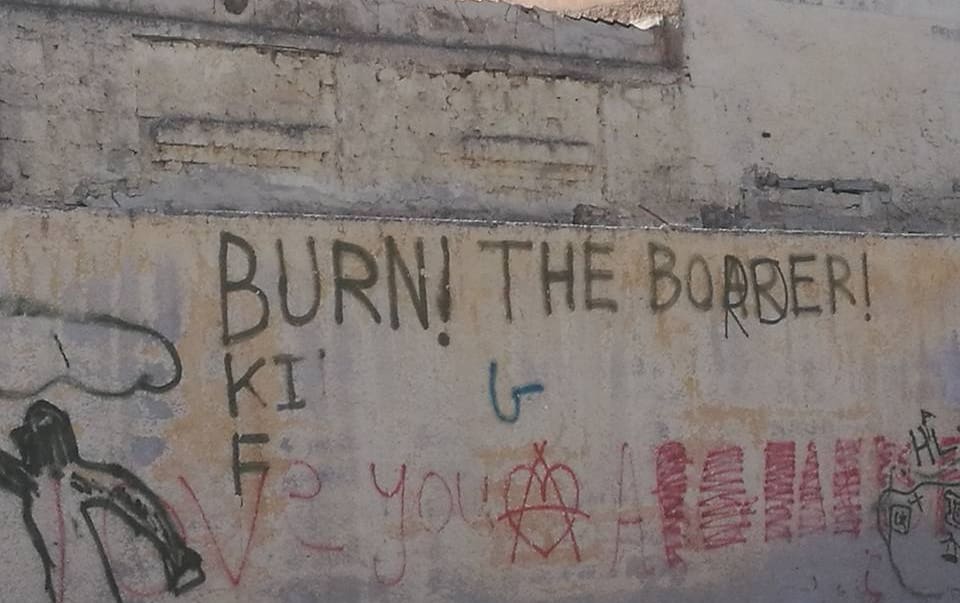

All images via Alarm Phone

Notes

i Great thanks to Alarm Phone member Marily for supporting Sylvie and Joelle, for writing down their stories, and showing them at an exhibition in Hamburg. She gave us the permission to re-print the images. You can find their full shipwreck story here. We also want to mention that it was due to the solidarity of volunteers and activists that Sylvie, Joelle and Victoria found support after surviving their horrible journey. Thanks to Refugee Rescue Mo Chara, Sea-Watch and No Border Kitchen!

ii You can find the whole story here. Thanks to W2EU for allowing us to share it! Yet another fascinating story, of a Moria detainee on Lesvos, can be read here, and there’s more and more where that came from.