Transcribed from the 28 April 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

People are angry about their stagnation, and about the yawning wealth hierarchies that are increasing in most places. The likeliest outcome, if people are angry, is that they’re going to do something about it…and what they seem to be doing is electing populist leaders. Those leaders then go on to violate human rights. That’s what I mean when I say that if we care about human rights, we should care about equality. The first turns out to be bound up with the second.

Chuck Mertz: Why don’t human rights challengethe inhumane practice that is neoliberalism? Because human rights aren’t about equality, even though you probably think they should be. Here to give us a history lesson on the relationship between human rights and neoliberalism, historian Samuel Moyn is author of Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World. Sam is professor of law and professor of history at Yale University.

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Sam.

Samuel Moyn: Thanks Chuck, nice to be with you again.

CM: There’s a term that we have to get out of the way and define right away in this conversation. You write, “The rewrite of the history of human rights offers another look for a new era in which, for all the current endurance of liberal political hegemony in the face of strong ideological opposition, its self-imposed crises seem more evident than before, and the relevance of distributive fairness to the survival of liberalism is impossible to avoid.”

What do you mean by liberalism? And how much does any lack of distributive fairness threaten liberalism?

SM: The word liberalism has been used in many ways over the past two centuries; for Americans, it has meant something like the New Deal—we could talk about what it meant back then. It did have something to do with economics. There was an attempt to reform capitalism at that time, and it had big effects.

What I meant, though, is that in the nineties, in the international order, we thought about promoting and exporting human rights, basic civil liberties, along with economic freedom. That was the form of globalization that triumphed, and we thought—unlike in the Cold War—that human rights mattered. We cared about the fate of individuals around the world…but we cared much more about the spread of markets. Now we’re seeing backlash to the results of that.

We can explain so-called populism in lots of different ways, in different places, but one of the key causes is rising economic inequality—which this free market strategy has driven. It has driven it in practically every country; all countries are getting more unequal in our time. The question is, what do human rights have to do with that? Do human rights turn out to be hostage to the economic disorder that’s causing a new nightmarish period to open up in world history?

CM: How are human rights being held hostage by neoliberalism?

SM: Lots of ways. You asked how to define liberalism; we also have to talk about what we mean by human rights. Americans have typically meant rights for people abroad. We rarely define our domestic problems in terms of human rights. We might talk about civil rights, when it comes to Black Lives Matter or other causes, but we define human rights as an external-facing idea. Even then we’ve really defined them to be only the most basic civil liberties: free speech, freedom from torture (assuming the US itself isn’t committing it), freedom from false imprisonment. These are the human rights that became central to US foreign policy in the seventies, when Jimmy Carter first announced such a policy, and also became central to the new NGOs of that period, like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, who also didn’t focus on economics.

Nowadays, a lot of international NGOs do focus on what are called economic and social rights: right to a job, rights to food, housing, clothing, a fair salary and workplace, even paid vacation. The US and many of its leading NGOs don’t support those rights, but many rights movements around the world do. The trouble is that even those rights often don’t work to promote socioeconomic equality.

There are two different problems. One is that most of the time, and for most Americans, human rights don’t have anything to do with economics. The other is that even those rights movements in the world that are promoting economic and social rights are also not talking about economic equality. As a result, we’ve lost track of that problem. Not only is that a terrible thing all by itself, but there is also a backlash. People are angry about their stagnation, and about the yawning wealth hierarchies that are increasing in most places.

The likeliest outcome, if people are angry, is that they’re going to do something about it. And what they seem to be doing is electing populist leaders. Those leaders then go on to violate human rights. That’s what I mean when I say that if we care about human rights, we should care about equality. Because the first turns out to be bound up with the second.

CM: As you were saying, during the Carter administration there was the emergence of human rights as a political policy—and at that same time, we also had the birth of neoliberalism.

How much do human rights exist as a response to neoliberalism? Or is it more of an unwitting partnership? Or are they just simply parallel to each other?

SM: It’s something like an unwitting partnership. It’s true that they have the same life span, and that the same president, in the American case, seems to kick off both things. But in the long run, I think that we should get a bit more complex about it, because the human rights movement and human rights law is a big thing, very multi-faceted, with lots of different people doing lots of different things. It’s certainly not just American, and it’s not just Jimmy Carter. There have been a lot of presidents since him.

For a lot of people, and especially Americans and American presidents, human rights have not had any relationship to distribution, because Americans have never embraced economic and social rights. But even for those movements who have embraced economic and social rights (and there’s an international law that protects them), those rights tend to be about protecting a sufficient minimum. Those rights say you should get at least enough of the most basic things that every decent life requires. Some amount of food, some amount of housing, some amount of pay. The trouble is that this doesn’t seem to be an egalitarian ideal. It’s a sufficiency norm. It says everyone should get enough.

It turns out that even that idea of economic and social rights is compatible with growing, not reducing, inequality. Even those groups and laws that pursue or protect economic and social rights are at best working on a floor of sufficient protection. They want every human being not to be destitute and miserable, and to have some basic minimum. Meanwhile, neoliberalism—this new political economy arising in the seventies and since—is trying to blow away the ceiling on inequality. It’s allowing the rich to get much richer, even as the poor are sometimes doing better.

That’s why there is an unwitting companionship. Neither of these two things are interfering with each other. One is building a floor, the other is blowing away a ceiling, and the result is greater and greater hierarchy—even as the lives of many more people turn out to be much more humane.

Human rights are a creature of the project of which they are a part. If they’re part of a welfare state, then they can fit with egalitarianism. But they can also be the companion of a neoliberal project, which means we need to put them back in connection with a new set of movements and projects, and make them part of an egalitarian politics as they once were.

CM: Why isn’t sufficiency enough? We always hear proponents of neoliberalism saying it has raised so many people out of poverty. Is neoliberalism’s success because it has found a way to make it look like it is helping out the poor, even though it’s just doing the bare minimum?

SM: Yes. First there’s the moral question: if we can get people out of poverty, haven’t we done enough? Does it matter if there’s inequality, or even if inequality is rising? This is a big debate among people who think about morality. I’ll give you an example. You’re probably familiar with a Princeton philosopher named Harry Frankfurt, who published a famous book called On Bullshit. He published a second little one called On Inequality, which makes the case that as long as we get people out of poverty, inequality doesn’t matter.

I disagree with that. I disagree with it on moral grounds, but also on pragmatic grounds. As we talked about before, it turns out that people who are in the middle class and are just stagnating are very dangerous. They were dangerous in the 1930s; they’re dangerous today. They’re not suffering from destitution; they’re suffering from stagnation. They’re the ones who vote in the authoritarian strongmen around the world. Even if we don’t think equality matters, we should care about those who are stagnating, and care about inequality for other reasons.

Then we get to your second question, which is even bigger and tougher. The first thing I have to say is that there are still lots and lots of poor people—more rather than fewer, mainly because world population is increasing so rapidly. But we’ve also seen—as a relative, proportional matter—a pretty big decrease over the last thirty or forty years in the percentage of people around the world who are living in extreme poverty, mainly because China has brought so many out of poverty.

You’re right that neoliberals will tell you we have to tolerate more and more inequality to end poverty. This is wrong for lots of reasons. Sure, we can’t look at what China has done and do anything but applaud. No one’s ever brought as many people out of destitution as China has under its version of marketization or neoliberalism. But the fact is, first of all, so many remain in poverty. And poverty is not the only evil out there. No one wants to be able to say that they lived in a society that got them out of destitution but left them in hierarchy.

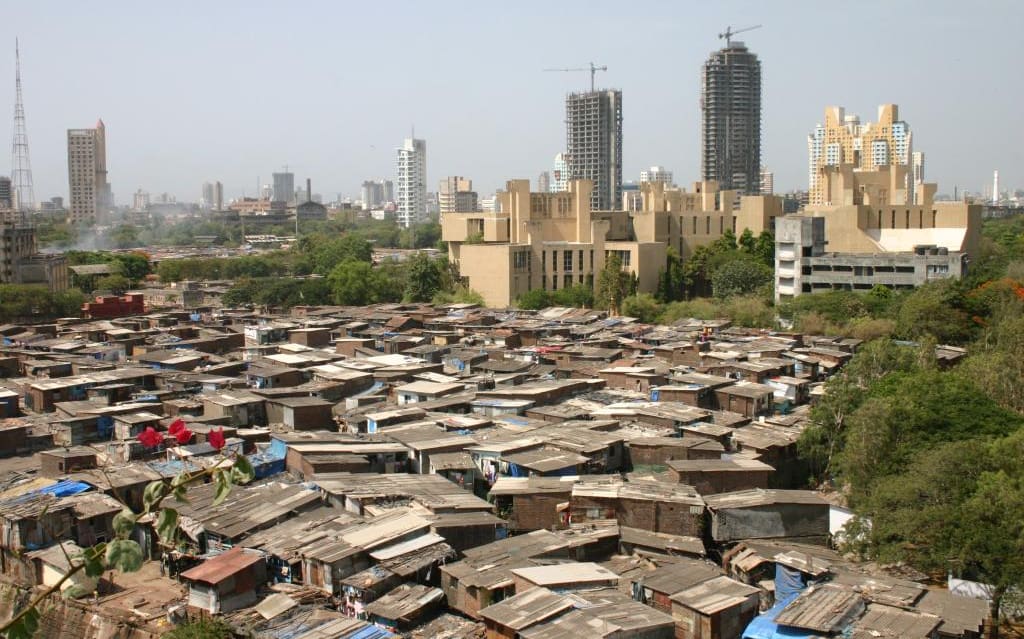

Hierarchy is also wrong—and as we’ve seen, it’s causing a lot of people to revolt. It’s true that in contrast to the nineteenth century, the first round of capitalist globalization, ours is more humane. That old version, in the nineteenth century leading up through the Great Depression, led to big worker’s movements, big socialist parties that changed the world. Ours is not immiserating enough people to create that big a backlash, but the backlash is happening in the form of populism, and it seems like people are angry not because they’re poor but because our form of capitalism involves lots of stagnation. People don’t think their children are going to do as well as them, and they’re right. And yet they see the rich winning. Every year, the rich are doing better and better relative to everyone else in many societies, including the United States.

We can’t rest content with neoliberalism even though it is more humane than nineteenth-century capitalism, and we need to find a new kind of social democracy that cares about the poor, but that also cares about the middle classes.

CM: You write, “It is as if in our highest ethics, material gains for the poor were all that could matter, either morally or strategically—when human rights placed any stress on material injustice at all.”

Isn’t material gains for the poor all that should matter when it comes to human rights? What do we miss in our understanding of poverty when we believe it can be “cured” by only material gains? Isn’t securing enough for everyone a way to confront neoliberalism?

SM: It is, where neoliberalism is causing poverty or keeping people in it. But as I’ve said, especially in the Chinese case, it’s also getting a huge number of people out of it. Then the question is: What can human rights do in the face of a situation where neoliberalism seems to make some people poorer and get some people out of poverty, but above all has the effect of widening the gap between the rich and the rest?

This is an area of big controversy. I published an op-ed in the New York Times that made some of these arguments, and a lot of human rights activists on Twitter and elsewhere insisted that they care about equality, they’re committed to it, they’re working on its behalf. And that’s true to some extent. This is a big change in just the last couple of years in human rights activism. For most of the history of institutional human rights activism, the big groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch didn’t care at all about poverty. Now they care about it some, and they do some things to oppose it. Today they even say that they care about how much inequality is increasing in our day.

I don’t think, though, that we should do more than ask human rights groups to care about poverty. I think human rights groups—having prospered so much, defining our highest ideals in this age of neoliberalism—should care that there is a connection between our interest in human rights and our tolerance of greater and greater inequality. But human rights groups strike me as the wrong kind of political actors to remedy inequality. They’re barely making a dent on poverty. After all, China is doing the most in that realm.

You mentioned FDR, and there were comparable welfare state politicians across the Atlantic in the 1930s and 1940s. If we ask ourselves who the agents or actors were who made a more equal society possible back then, our first answers are trade unions and socialist parties—or at least a Democratic Party like the one under FDR, that was very different than our neoliberal Democratic Party. We need to get actors like that back if we care about equality. That’s a hard task. It just doesn’t seem like human rights groups are up to the challenge of facing neoliberalism, insofar as it’s really been a recipe for such huge hierarchies, as we see in so many societies—increasing every day.

CM: Did human rights used to stand for equality but they no longer do? Did something change? Was it the fall of Soviet Communism that sent the message to the world that the pursuit of equality was not only disastrous but futile?

SM: Yes and no. In the middle of the twentieth century, at the time of those welfare states, the United Nations was founded. FDR passed away right before the end of World War Two, but he’d already signed off on the creation of the United Nations, and his wife Eleanor famously went to the UN as a widow and helped write the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which the UN propounded in 1948.

If we look at that declaration, it has all the economic and social rights we’ve discussed. The rights to work and housing and food, a humane workplace, fair wages. Americans actually supported some of those things back then, although it’s scary to note that the first politician to try to get a universal right to health for Americans, Barack Obama, seems to have incited a huge backlash, and Donald Trump, for whatever reason, made a lot of hay of that attempt.

We have to make big changes, because right now the rich are lifting off. They’ve already ascended so far beyond the rest that it’s like they’re on another planet, and we have to bring them back to Earth.

But when we look back, even the universal declaration doesn’t say anything about equality. And yet, all of the societies that created welfare states in the thirties and forties cared a lot about equality. You’ve probably discussed the famous economist Thomas Piketty and his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. He’s shown that it’s precisely in this era of the welfare state, from the thirties through the fifties, that inequality was relaxed most in the United States. The rich were brought down, through antitrust and high taxation and lots of other schemes, to be part of our society. After 1975, the lid was blown off, and the rich were allowed to win again, ascending higher and higher.

The way I would put it is to say that human rights were one part—a small part—of a broader project which we could call the welfare state. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 was a template for the welfare state, which was an egalitarian project. But then something big happened, and it happened at the same time neoliberalism launched in the seventies. Human rights got defined in a different way. It was really a language for the suffering abroad, especially for Americans, and their most basic entitlements—free speech, freedom from torture, freedom from false imprisonment, maybe some very basic economic and social rights defined in terms of subsistence.

In the ways we’ve discussed, the idea of human rights has proved to be compatible with increasing inequality. The lesson of my research is that human rights are a creature of the project of which they are a part. If they’re made part of a welfare state, then they can fit with egalitarianism. But they don’t have to be part of a welfare state project. They can be the companion of a neoliberal project, which means we need to put them back in connection with a new set of movements and projects, to make them part of an egalitarian politics, as they once were.

CM: I think we need to define what we mean when we’re talking about equality. Is equality like objectivity in journalism—that we know that nobody can be perfectly objective, but it should be the journalist’s goal? Is equality unattainable, but it should be the goal?

SM: We have to think about these moral issues very carefully, and fortunately a lot of philosophers have done so. The first thing is to distinguish between equality of status and equality of distribution. The first means that we should all be treated the same no matter what kind of person we are. No one should be mistreated because she’s a woman or he’s black or they’re queer. That is an ideal we’ve embraced like no society ever before. And those welfare states I was just praising for equality were not very good when it came to status equality: women remained in the home, blacks remained under Jim Crow. Analogous things could be said about welfare states across the Atlantic. The Swedish welfare state, a famous one, was connected to eugenic thinking, for the sake of the Swedish Volk.

But while we’ve embraced status equality, we’ve lost that second kind of equality, which is material or distributional equality. That means an equality of who gets what, so we’re really talking about income and wealth and all the things that money can buy. There, we’re doing much worse in the current period. Much, much worse.

The question is, what should we shoot for? I think the people who lived in the era of the welfare state had it right when they said that we should try to live in a relatively equal society, mainly so we all feel part of the same venture. The rich shouldn’t be on another planet living a totally different life with totally superior opportunities that no one else can have. It’s not enough to get the poor out of poverty if the rich are leading a different life and in effect living in a different society, buying themselves out of all the things that we have to deal with in our day-to-day lives.

Then we have to debate: what’s good enough? I don’t hold out for totally equally outcomes. That would be not only unfeasible but it might well mean we have to sacrifice growth to get it. Not a lot of people want to be equal in the way that primitive tribes lived with everyone equal. We want to live relatively equally in circumstances of wealth and growth. That was what the welfare state was about, and of course there’s lots to argue about when it comes to what that means exactly. But once we see that’s what we’re looking for, we can at least have that argument.

Whatever the answer, it means we have to make big changes. Because right now the rich are lifting off. They’ve already ascended so far beyond the rest that it’s like they’re on another planet, and we have to bring them back to Earth.

CM: Earlier you were pointing out the difference between civil rights and human rights. Now, when you’re discussing expanded status rights: how much is society paying for those expanded political status rights with economic inequality? Is this some kind of grand bargain with neoliberalism that we have all made, whether we have done so unwittingly or not?

SM: I think so. It raises a really hard question for someone like me, because it seems the case that if you want everyone treated alike, people will want to have less to do with one another, and they won’t feel like they’re part of the same community anymore. Conversely, if you want people to treat one another with lots of solidarity, you might have to exclude some people. That’s what the welfare state did. To put it in a scary way: a lot of people think that if we want everyone included, the best we can have is weak and cheap solidarity; if we want strong and costly solidarity, we may have to get some people out first, or draw the circle of solidarity more narrowly.

If any of that is true, it looks like we made a choice at some point after World War Two: in all these different countries, we first created a welfare state for white males. That’s what FDR tried to do. The mystery is that his voters became Donald Trump’s voters, and the reason is: we decided to include lots of new people. Women above all, but also blacks, some kinds of immigrants (in spite of the way that migrants are often treated in this country and in so many others). The politics of LGBTQ rights and disability rights are also part of this picture.

I want to say that there’s no reason why we can’t expand the circle of solidarity and still keep it strong and costly. It’s a political difficulty, how we include more kinds of people while still getting the people in the circle to feel that they’re included and that they’re part of the same community. But we’ve let the white males stagnate—especially in Trump’s swing states, the post-industrial Midwest—and we’ve benefited others. And they know it. Now: it was right to do so, because blacks and women were treated shamefully for so long. But then look what the white males do in response. They are spoilers. They vote for populists, and that seems to be something that’s happening across the Atlantic as well.

I don’t think there’s any choice but to figure out how to reconcile status equality—fair treatment for all kinds of people—with material equality so that we all live in roughly equal circumstances, so that no one feels like voting for someone to wreck society.

We shouldn’t rest content with any scheme that says that all morality requires is some basic minimum. Equality matters, too.

CM: I was going to ask how much the welfare state’s experiment with equality was undermined by racism, sexism, and other forms of inequality that were being experienced at the time. But are you saying, then, that it wasn’t the racism and sexism that undermined the welfare state’s experiment with inequality, it was the fact that it became more inclusive that undermined the welfare state’s experiment with equality?

SM: Absolutely. Most historians would say that when transatlantic states, including the United States, set up welfare states, they did so by relying on racism and patriarchy, privileging white males. The question is, how could you cure the welfare states of these original defects? There have been attempts: Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, was in part a post-Jim Crow experiment to try and make institutional civil rights have a class component, an anti-poverty component. Welfare-state American liberalism had a chance to maintain FDR’s liberalism while including new sorts of people: liberating women, doing something much fairer, at least, for blacks—who were not only under Jim Crow but had been excluded from most of FDR’s generous social programs (a good example is the GI Bill).

That’s the problem of our time. In a way, we’ve begun to confront racism and patriarchy more than any human beings ever have. But we’ve done so while losing the material equality and the welfare state we’d begun to construct at least for white males. We need to figure out how to put these two things together. That’s our problem and project.

CM: If the welfare state is where we find in history the greatest equality, to what extent do you think those who oppose the welfare state are really in opposition to equality? To what degree is our political divide between those who support equality and those who oppose it?

SM: It’s probably too hard just to put people on two sides of that line. There are lots of people who think that some forms of equality—like the status equality I was mentioning—matter, but don’t care about material equality. Most of the leaders of the Democratic Party since the seventies have been like that. A good example is Hillary Clinton, who wanted to crack the glass ceiling and stood for a certain kind of feminism, but was in bed with the neoliberal transformation of the Democratic Party. That teaches us that you can be for and against equality. You can embrace the project of getting people treated more equally, no matter the kind of person they are, while tolerating the victory of the rich over the rest. That’s the story of Clinton and Goldman Sachs and all the rest of it that Bernie Sanders opposed.

It’s not easy to say there’s equality and some people are against it and some people are for it. When it comes to material equality, we’re learning more every day that the young are more and more for it. They are willing to talk about socialism. They’re willing to get out there for Bernie Sanders. They’re willing to say that they don’t think capitalism as we know it is a fair economics. And we can imagine a future in which—without going back on all the feminism and gay rights and civil rights movements we’ve seen in the past half century—we can return to FDR’s project, which was material equality, and figure out how to fit these two together.

Of course, the rich are going to be our enemies. We have to figure out how to scare them in the way that they were scared in the thirties and forties, to come back to Earth and join us in our society on relatively more egalitarian terms. Pay more taxes. Submit their multinational corporations to regulation and taxation. These are big projects that we’ll see pursued in the next decades.

CM: How much do you think human rights activists understand the way human rights exist today and that their not challenging neoliberalism has to a certain extent led to inequality?

SM: They understand it more and more. They understand that in the seventies, when they first founded human rights movements, they forgot about the universal declaration, its economic and social rights, and the broader welfare state of which it was a part. They had reasons to do so, because you’ll remember that in the seventies, human rights activists were facing totalitarian states in Eastern Europe and authoritarian states (which sometimes Americans had helped bring about) in Latin America, in the southern cone, in places like Argentina and Chile.

After the Cold War, there was a chance to reset, and as I’ve mentioned, some groups began to say that economics were part of human rights, that they mattered. But the human rights movement still looked out at the world and let neoliberalism take off—didn’t say much about it; said, if anything, that what’s in the constitution of a country matters, that judicial independence in a country matters, and maybe that economic and social rights matter…but these are places (both Eastern Europe and Latin America) that got very unequal very fast. Maybe human rights activists thought, like neoliberals, that the game was worth the candle, or maybe they thought they’d get around to inequality later.

Regardless, in both of these critical periods, the seventies and the nineties, there was selective attention, and there was not a return to the welfare-state broad egalitarian idealism of the 1940s. And now we’re paying the price. A lot of people in human rights communities and people who care about human rights either think that it’s time to reassert the importance of equality, or they think that if we don’t reassert it, human rights themselves, the rights they care about, will be at risk. For either of these two reasons, we’re at an inflection point.

Of course, the main prestigious human rights outfits, ones like Human Rights Watch, will never pivot. They’ve got too much history. Their funding depends on what they’ve been doing since the 1970s. And frankly, they’re very good at their narrow mission. But the rest of us need to think: how much do we want to support that mission? Do we want to put all our eggs in that basket? Or do we need to think about a new mission alongside the old mission? It’s not a mission that exists in the human rights framework, although people who care about human rights may care about it. We don’t need to reinvent the human rights movement. Rather, we need new movements, things like the trade unions and socialist parties that once were the engines of more egalitarian societies.

CM: You write, “Though one might hope that sufficiency, especially if defined upward, might lead to equality, it is equally possible that the poor will come closer to sufficient provision as the rich reap ever greater gains for themselves. In practice, sufficiency may get along better with hierarchy than with equality.”

This week, Finland ended their universal basic income program. Is UBI a form of sufficiency? And is it possible that UBI could lead to greater inequality and more hierarchy?

SM: Absolutely. Universal basic income is just another version of economic and social rights. It says we should just give people a certain amount of money, where economic and social rights says there’s a list of key items in the good life—housing, food, water—and you can’t just give people money, you have to give people those things. But ultimately they’re very similar. And the reason why not just the left but the right has gotten enthusiastic about universal basic income is because it’s compatible with inequality—maybe even expanding inequality.

That’s not exactly the reason why Finland is taking a second look at its universal basic income experiment, but whatever we think about Finland, we shouldn’t rest content with any scheme that says that all morality requires is some basic minimum. Equality matters, too.

CM: Sam, I really appreciate you being back on our show. Thank you very much.

SM: Thank you, I appreciate it, Chuck.