Transcribed from the 30 June 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

With this new Christian god who can see into your soul, it became really important to Roman rulers to control what went on in the souls of all their people. To prove that you’re a Christian, you have to do more than just turn up at church. You have to show that in the very heart of your heart you believe. The soul of yourself is no longer free; it belongs to the rules of the state. That’s when the real persecution starts.

Chuck Mertz: Christianity destroyed the classical world methodically and without remorse. Christianity didn’t win some intellectual battle royale, proving its superiority over the classical world; no, Christianity annihilated the classical world. Here to describe that destruction, journalist Catharine Nixey is author of the new book The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Catharine.

Catharine Nixey: Hello, thank you very much for having me on.

CM: It’s great to have you on the show.

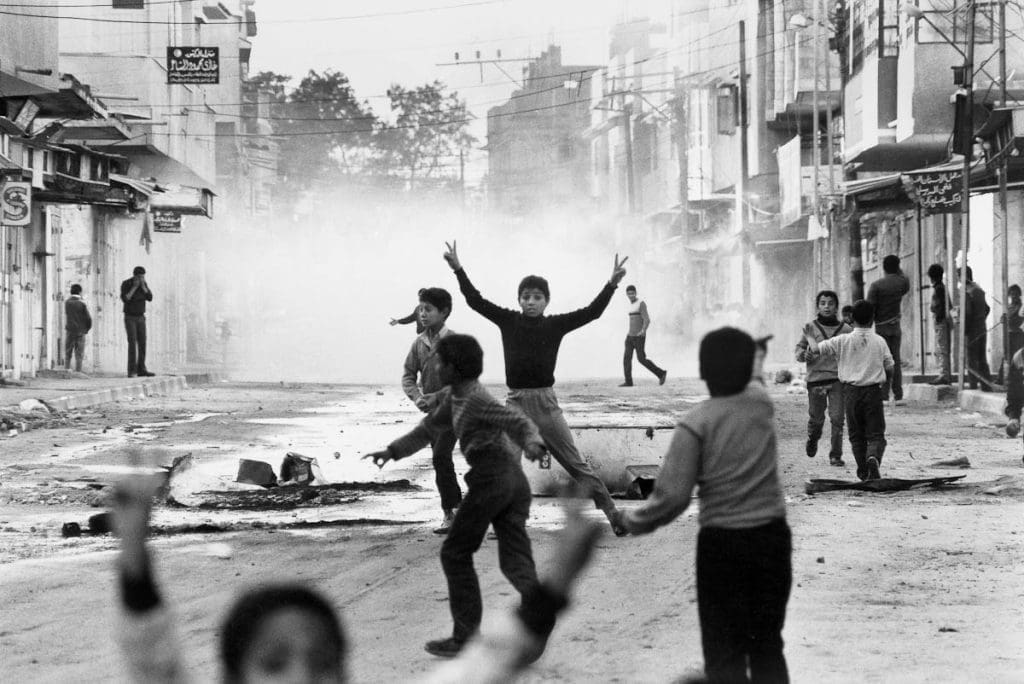

You write of the attacks by early Christians: “The destroyers came out of the desert. Palmyra, in Syria, must have been expecting them for years. Marauding bands of bearded, black-robed zealots, armed with little more than stones, iron bars, and an iron sense of righteousness, had been terrorizing the east of the Roman Empire.”

You use the word terrorize. Would you call what the Roman Empire and Christianity did “terrorism”? Why or why not?

CN: When they struck, yes, it was definitely terrorism. This isn’t my word, this was the word that the ancient authors themselves used.

There’s a philosopher called Hypatia, she’s quite famous, she was one of the most brilliant mathematicians of the era—and she was taken out of her chariot by Christians who thought that because she wrote with mathematical symbols and used an astrolabe (she was also an astronomer) she was a creature of hell. They didn’t know math, they didn’t know astrolabes; they thought these were demon tricks. So they pulled her out of her carriage and they flayed her alive. It was said that while she still gasped for breath, the Christians gouged out her eyes.

In that particular crash between the Christians and the pagans, the very word we get in the Roman legal documents is terror. It is a Latin word—they say these people are creating a great terror and they have to be stopped.

So yes, it really was terrorism, because it caused terror. When Christianity arrived, they wanted everyone to convert, and they wanted them to convert fast, and they wanted them to stop worshiping their other gods, and one of the best ways for them to do that was to smash their temples and show them that the physical power was on the side of the Christians.

CM: Did ignorance, then, defeat intellectualism?

CN: There were some very learned Christians, but yes: we lost ninety-nine percent of all Latin literature in the centuries following Christianization. We lost ninety percent of all classical literature in total. It was horrific what was lost. And some of it wasn’t merely “lost:” there were the occasional bonfires of books, and there were philosophers who were chased from the Empire, and schools were shut. But most of what was lost was lost because people started to say, “I’m not going to read these evil pagan books; I am going to read the only singular book that matters, which is the Bible.” And there were the works of saint Augustine and all those things.

A particular kind of knowledge (if you want to call it knowledge), the kind in the Bible, suddenly became all-important and everything else became unimportant to the point of being reviled and feared. There were rules that said to stay clear of all pagan books in Assyria.

And it’s a very different idea. The usual Christian way of telling this story is that the Christians preserved the works of the classical world. But if you look at the numbers, that’s really not the case.

CM: Is this more about a goal of Christianity to erase the past, or is it more about the Roman Empire’s goal to erase and replace the past? Can we blame this on Christianity, or can we blame this more on the Roman Empire?

CN: The point where it all starts to go wrong is when the Roman Empire turns Christian; when the emperor of Rome says, “I am now a Christian.” Following that, in the next hundred-year period, is when the laws start to appear. Law after law appears, saying you can’t debate in public; you can’t go into the temples. Eventually the laws say the temples should be demolished. Laws are also passed making it illegal to be anything other than Christian. Laws are passed saying if you go back to your old pagan ways, you will be put to death. A particular school in Athens, the Academy (which traced its history back to Plato), was closed because there were laws passed against it effectively meaning that philosophers could no longer continue in their work.

Christianity in that period couldn’t allow you to believe anything else. They said if you believed something else, then you believe something evil, something demonic. The world at this point starts to split into two, into good and evil.

CM: Was this kind of fanaticism, this uncompromising zealotry, common in human history prior to the Roman Empire? Because now we’ve seen it with the Khmer Rouge and the way they’ve tried to erase their history; we’ve seen it with the Taliban and how they’ve tried to erase their history; we’ve seen it with ISIS and how they’ve tried to erase their history. Is this something that we can see as consistent and commonly happening over and over again throughout human history? Or did this start with the Roman Empire and Christianity?

Some of the greatest thinkers of the early church encouraged their congregations to go and smash up temples. Saint Augustine said that the smashing of other temples is what god wants, what god wills, what god commands. He also says not just to attack their temples, but to try and convert other people. He advises that if people won’t convert willingly, then you should use force.

CN: In the period I’m looking at, it starts with Christianity. They take some from Judaism. Judaism advises ways in which you can smash idol statues to get the demon out of them: you can gouge the nose and eyes out of statues; you can drag them around in the dirt and that might get rid of the demon. It’s from the Old Testament and from tracts such as that that Christianity gets the inspiration for what it then does next.

But really it wasn’t commonly done in the Jewish world. It was a Christian innovation to do this. People had smashed statues before, but this religious fervor that says you must be my religion, otherwise you’re done—that is new. That is very new, and it spreads with Christianity. It spreads as Christianity gets its foot into the corridors of power. That is when the danger begins, and that is when the huge destruction of art I write about—the most massive destruction of art that human history had ever seen until that point—begins. That’s when the Christians go around smashing up statues.

To me it looks very clearly like the problem is monotheism. The Romans were polytheistic, though we call them pagan. They would never have called themselves that. To be honest, before the Christians you’d never have described yourself with your religion at all. In pagan texts, they say it doesn’t matter what you worship; everyone believes in different things, and everyone thinks what they believe is best—that’s totally natural. And there are pagan writers arguing with Christians. When the Christians start to smash their temples and take their altars, they say, “Please, what are you doing?” “We see the same stars,” writes one orator. He begs them to stop and says, “We see the same stars; the same sky is shared by all. What does it matter what route we use to seek the truth?” The Christians take his altar and say, “It matters to us. If you’re not Christian, then you are damned.

CM: Is this, then, the first politicization—and even government weaponization—of religion?

CN: In the Roman world and the Greek world, politics and religion were absolutely interwoven. What changes in the Christian world is they start to care what everyone in the country thinks. In the Roman world, if you went to the senate you would have made a sacrifice before you went in. That was common. Religion was everywhere. What changed with Christianity was that the government started to say that in your own home, you can no longer do what you want. The Roman government had never sought to bother over what people did in their own home, and certainly never sought to know what went on in someone’s heart. But suddenly with this new Christian god who can see into your soul, it became really important to Roman rulers that they controlled what went on in the souls of all their people.

That is when there were really vicious attacks. To prove that you’re a Christian, you have to do more than just turn up at church. That’s not enough. You have to show that in the very heart of your heart you believe. That’s when things turn nasty. The soul of yourself is no longer free; it belongs to the rules of the state. That’s when the real persecution starts, and when such things as heresy and crimes of religion become a real issue.

CM: I couldn’t help but notice that the time frame in which you put this destruction of the classical world by the Roman Empire and Christianity (the fourth to sixth century AD) coincides with the beginning of the Dark Ages, which happened as the Roman Empire was not only in decline, but also in the process of destroying the classical world.

How much does the Roman Empire’s fall account for the Dark Ages, and how much does their destruction of the classical world account for the Dark Ages?

CN: The English historian Edward Gibbon blamed Christianity for a lot of it. One of the things that frightens us, I think, when we look at the Dark Ages, is the idea that your soul is no longer free, and this feeling that it’s kind of a police state, that you can’t step out of line; you can’t do what you want or you could get into trouble. This narrowing of the intellectual free liberty of every human—that is what starts now.

But also: we lost a lot of books, and it does grow into a dark age. The very reason we call it the Dark Ages is because an Italian historian, Petrarch, looked back from the Renaissance and said, “I can’t believe that the Christians shut the oldest and greatest philosophical school in Athens,” and he and others of this period dated the Dark Ages to this symbolic moment. The Academy had been where Plato had taught, so to shut it was as if the whole classical world was ending.

It wasn’t the same Academy, though, and you can make lots of arguments about how different the philosophy was—and it was; it was closer to theology in some ways—but it was at that moment that they said philosophical argument is no longer. Philosophy cannot disagree with the Bible from now on. If it does disagree with the Bible, we are not going to put up with it.

Christians in this period commit suicide because they want to die a martyr’s death and be celebrated forever in heaven. If you’re an absolute nobody on Earth, die a suicidal martyr and in heaven you’ll be celebrated, plus you’ll be famous on Earth. This idea of suicidal martyrdom spreads first in certain areas of North Africa, and people start calling the people who are committing suicide a death sect.

CM: How successful was Christianity’s erasure of earlier civilizations? How difficult was it for your own research? How successful was their strategy of conquering Europe by erasing the past?

CN: There are other causes of this erasure, I should say. There were barbarian invasions and things like that—although the Germans, interestingly, call the barbarian invasions the “great migrations.” It just depends on how you look at them.

There are lots of causes for what happened to Rome. Hyperinflation, several plagues. But Christianity definitely didn’t help. The problem with monotheism, in my view, is less the -theism than the mono-. What we lost was the idea that you can think what you want and do what you want and joke about what you want—what you lose is a spirit of humor.

For the Romans, what they write about religion had often been very funny. There’s this guy called Celsus—he’s the first critic of Christianity we have; he’s writing in the third century. And he says things like, “I don’t believe that god would have had a child with Mary. He’s god. He could have literally any woman he wants. Why does he go for some poor nobody in a backwater? He would totally have had a queen at the very least.” And he says he thinks Mary got knocked up by a soldier called Pantera, and that she made up this story to cover her tracks—which would probably be the biggest and most influential lie in the world if true. He said things like, “I don’t believe god made the world in seven days. If he’s an omnipotent god, surely he could just make it in one day. Boom! Why does he have to piece it out bit by bit and then have a rest, like a bad builder, on the seventh day?”

These kinds of criticisms feel almost shocking to us now, because we don’t make jokes about religion, really, anymore. When Monty Python made a similar joke about Mary not really bearing the son of god, the film was banned—and that was in the 1970s. So one of the things we lost is the idea that you can laugh and joke about anything, and criticize anything. Some things become very sacred at this moment, and we never get that humor back.

And the reason people don’t know about it, why they don’t write about it, is that mostly when people have told the story of Christianization, they have told it from the point of view of a Christian—and even if they’re not Christian, using only Christian sources. So we don’t very often see it from the other side. But the other side were often horrified. Some weren’t, some were fine, some converted happily. But many said things like, “We are being swept away by the torrent. We are men reduced to ashes. Everything has been turned on its head.” Those are the kinds of phrases. You get that people are terrified.

CM: Could this Christian destruction of the classical world also be described as some other kind of crime against humanity? Was it ethnic cleansing? Genocide? Is there a category of crime against humanity that best describes this violence?

CN: It’s a religious war in its latter stages. That’s the best way to understand it. It’s not ethnic, because religion in the ancient world wasn’t ethnically distributed, and nor was Christianity. Christianity was everywhere among everyone. It was a religious war that turned an empire on a sixpence. When the first Roman emperor becomes Christian at the start of the fourth century, the way the Christians tell it is that it’s the end of persecution—that the Romans had been being horrible to Christians before and now everyone who wants to be Christian can be Christian.

It’s not. That is the beginning of a century by the end of which basically everyone is Christian. When the emperor came to power, fewer than ten percent had been Christian. It wasn’t a great relief to have a Christian emperor. It was a total surprise, and within a hundred years, the whole empire had to follow. It was a massive and very rapid conversion.

The Christians say they converted everyone by a hundred years later—they say there were no pagans left. That’s obviously not true, but they are pretty confident.

CM: How does this kind of destruction have anything to do with our true Christian beliefs? Was this done in the name of a religion that would not condone those actions? Or does the Bible preach a law of retribution and violence? Does Christianity in some way lend itself to being exploited in this way?

CN: The Bible is a broad church. If you want to find a sentence for this or that, you can find it. “I am a jealous god. You shall not worship other gods, you shall have no other god but me.” What’s interesting is he’s not denying that there are other gods in that. There are other gods, but you’re not supposed to worship them. So it’s there in the ten commandments. It’s there in the heart of the religion itself. There are passages in Deuteronomy that say you should destroy other temples. It’s absolutely there in the Bible.

Some of the greatest thinkers of the early church encouraged their congregations to go and smash up temples. Saint Augustine said that the smashing of other temples is what god wants, what god wills, what god commands. He absolutely takes it for granted that his fellow Christians will be doing this. And he also says not just to attack their temples, but to try and convert other people. He advises that if people won’t convert willingly, then you should use force. He said it’s not cruel to do this; it’s a bit like a father beating his son with a rod or a schoolmaster correcting a child. You’re beating them but you’re doing it out of love. You’re like a doctor cutting out a canker, or like somebody stopping a small boy stepping on a snake using the force of your hand. He says this is what you are doing if you make someone convert to Christianity. You’re not doing a bad thing, even if you do it by force, because otherwise their soul will perish.

So saint Augustine, the Bible, and the greatest figures in the early church all encouraged this. They thought it was totally natural—if not a good deed.

CM: This is kind of a chicken and egg thing, but was Christianity simply a convenient vehicle to use as law and rationalize Roman imperial intentions? Or was it Roman imperial intentions that were motivated by Christianity?

Christians disliked bawdy, free, liberal Roman poetry. They disliked things like Sappho’s writing; she’s a lesbian poet, so some of her works were burned, and Christians also destroyed her poems by not copying them out, and attacking existing manuscripts. They destroyed philosophical works as well.

CN: This was all within the same empire. It doesn’t really change the borders of the empire. It’s an empire converting itself. So is it imperial ambition? The thing about the Romans—the Christians will later make a lot of martyrs. They’ll say that the Romans were trying to convert people away from Christianity. But Romans almost never martyred Christians. They really weren’t that interested. There are amazing accounts where Romans try and persuade Christians not to insist on being martyred.

There’s this governor, Arius Antoninus, and one morning he’s at work, and he finds that all the Christians in the province have turned up before him and requested that he execute them, because they want to die a martyr’s death. When the Romans and the Christians clashed early on, when there are stories of martyrs and saint Paul and things like that, what’s happening is often less that the Romans are hunting out the Christians than the Christians are turning up in front of the Romans and saying, “Execute me, because I want to be a martyr.”

There is a Christian text that says, “If you die a martyr’s death, in heaven you will have a hundred times the reward, a hundred times the children, a hundred times the family.” So Christians in this period commit suicide because they want to die a martyr’s death and then be celebrated forever in heaven. You could argue that there are good reasons for doing this. If you’re an absolute nobody on Earth, die a suicidal martyr and in heaven you’ll be celebrated, plus you’ll be famous on Earth. This idea of suicidal martyrdom spreads first in certain areas of North Africa, and people start calling the people who are committing suicide a death sect. People are very frightened by this, this willingness to commit suicide because you think you’ll be worshiped in heaven.

That is particularly Christian. It’s not Roman at all. Roman beliefs were more a matter of performing certain actions: going to the temple and doing a sacrifice. It wasn’t about belief in yourself; it wasn’t particularly about an afterlife. They seem conflicted about whether or not there is one; they seem fairly certain it won’t be fun if it does exist. Roman religion was more a thing that was all around you. In the air but not necessarily in your soul, and not something that you went on about at great length.

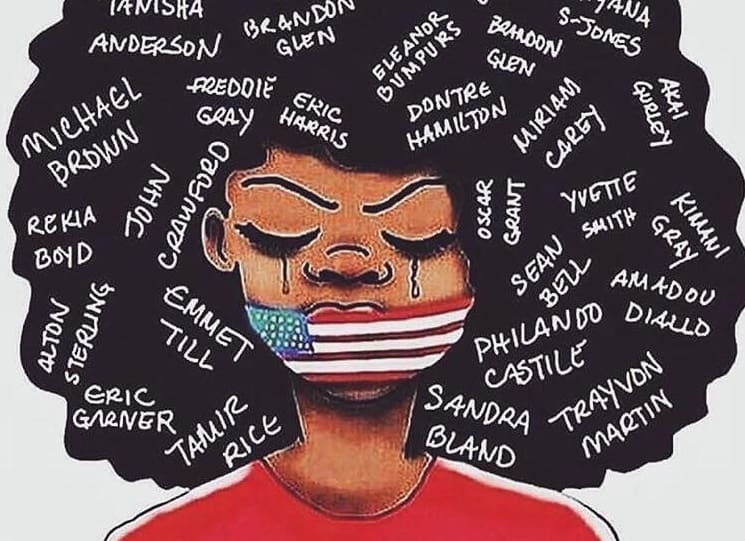

CM: Being rewarded for martyrdom obviously sounds a lot like the typical criticism that people have of Islam and of Muslim extremism and Muslim militancy: that they think they will be rewarded with heaven if they are martyred. So how do you feel about the kind of media narrative that says Islam is a suicide or martyrdom-seeking religion, when you can find it in the Bible as well?

CN: It was there long before in the Bible. We just think it’s new because we don’t know enough history. We see so many of these things in Christianity. It’s easier, I suppose, to say it’s nothing like what we do—we’d never do that! We’d never smash up Palmyra! We’d never commit suicide because we think we’ll be a martyr in heaven! But of course this is a human thing to do. It’s certainly an odd human thing to do. But it’s a human thing to do—not necessarily an Islamic thing to do.

There’s this narrative that it’s very Other, and it’s nothing of the kind. And equally, the vast majority of Muslims feel as the Christians in the period did: you see them writing things to each other like, “What are these crazy people doing? Why are they killing themselves?” This is frightening, this is weird, this is Other. There’s always going to be a spectrum of people within a massive community, and Christianity has suicidal would-be martyrs, and Islam has suicidal would-be martyrs. If you preach the idea of an afterlife strongly enough, it makes sense that people would want to get to it faster.

Greek religion and Roman religion both had strong strains of skepticism in them. There’s a story of a Greek philosopher who gets shown around a temple by a Greek priest—he’s a priest of a past religion, Orphism, that said there is an afterlife. And the priest is going on and he’s saying it’s much better after you die, it’s amazing, and once we die we’ll be in this wonderful afterlife. And the philosopher just says, “Well, then why don’t you die?” It’s a good question. If you believe in heaven that strongly, why don’t you die?

CM: Did Christianity annihilate whatever older religions they encountered? And how well is this understood by other religions today? How much does the annihilation of previous religions by Christianity form the opinion of Christianity by other religions today? Is Christianity seen by other religions as an invading force that’s always trying to take over?

CN: I don’t think it’s well known. Most people don’t know about this period, because history is written by the victors. Until 1871 there was pretty much only the ordained teaching at Oxford and Cambridge, and they were the main universities going then. Even now, when people write about this, they don’t use non-Christian sources, just Christian sources.

As far as how much Roman religion survived: in the eighth century, there was still some pagan worship going on in Cyprus; if you travel now to what then were the fringes of the Roman Empire, you’ll find what are basically pagan festivals that have now gone under a Christian cover.

We can look at Christmas itself. On the twenty-fifth of December, in Roman times it was said to be a nativity of Sol Invictus, the unconquered sun. And the sun, S-U-N in this case, was supposed to be born on the twenty-fifth of December; people went into the shrines and they came out at midnight, and they said the virgin has given birth, and then everyone celebrated this midwinter festival. You don’t have to think that hard to hear an echo where a virgin gives birth on the twenty-fifth of December in our own time.

A lot went away, a lot was reconstituted, and some bits survived.

CM: You write, “It is true, monasteries did preserve a lot of classical knowledge. But it is far from the whole truth. In fact, this appealing narrative has almost entirely obscured an earlier, less glorious story. For before it preserved, the Church destroyed.”

Is Christianity, then, both the curator of classical knowledge and the destroyer of it?

They saw the world through a veil of religion, and it changed the way they saw other human beings: they rated them. They wouldn’t have said it like this, but they automatically rated other people as less good than themselves because they weren’t religious. That is so dangerous.

CN: It’s the curator of the very little that was left. The way it destroyed classical knowledge was by arguing against it all the time, by saying it was terrible, it was filth. There are lots of Roman poets who have only just now been translated in the late twentieth century, because they were considered too rude. I’m sure I cannot say one of the lines of a Catullus poem on air, because you’d have people complaining, but Christians disliked this bawdy, free, liberal Roman poetry. They disliked things like Sappho’s writing; she’s a lesbian poet, so some of her works were burned, and Christians also destroyed her poems by not copying them out, and attacking existing manuscripts.

They destroyed philosophical works as well—there were lots of Roman works, partly those that argued against Christianity, but also ones that said, “Don’t worry about the gods, we’re all made of atoms. You don’t have to worry about pleasing these deities. They don’t exist. We’re just atoms.” Obviously the Christians had to attack them. They attacked them verbally, by slandering them and blackening their names.

When we say epicurean today, we mean someone who eats and drinks and gets drunk. Epicurean actually meant someone who was quite frugal. Epicurus said, “Give me a pot of cheese and I will feast for a week.” In other words, what matters is how much you enjoy how little you have. And Epicureans also argued that the world was made of atoms. The Christians attacked them vehemently and said these people are drunkards because they say pleasure is the highest goal—but that’s not what they meant. And the reason Christians attacked them—verbally and on paper—was because they threatened the basis of Christianity. They threatened the idea that you were going to be punished by god. They threatened the idea that you should believe in gods at all.

CM: You write, “Books, which were often stored in temples, suffered terribly. The remains of the greatest library in this ancient world—a library that had once held perhaps seven hundred thousand volumes—were destroyed in this way by the Christians. It was over a millennium before any other library would even come close to its holdings. Works by censured philosophers were forbidden, and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.”

How anti-knowledge, anti-science, and anti-art was Christianity? This is starting to remind me of 1930’s Germany! Is this about being anti-knowledge, anti-science, anti-art? Or was it about being anti-pagan and those things were just unintended consequences?

CN: At first, it was emphatically about being anti-knowledge. Literally in the Bible, saint Paul said, “Wisdom is foolishness.” This is repeated again and again. Christianity praised those with no education. It praises saint Anthony, who goes out to the desert and says that he scorns schoolbooks. Saint Augustine loved saint Anthony. There’s a great celebration of ignorance.

Later they will start to assimilate non-Christian knowledge, but they feel very awkward about it. They don’t like knowledge. They don’t like the clever Romans. They say that you don’t need learning to be near god, you just need to believe. Later, they start to assimilate this classical knowledge because there’s no way they’re going to convert everyone. They realize that elite Romans think Christianity is stupid. This is one of the things they’re always writing: Christians are stupid, they’re ill-educated, they don’t know anything, their story is stupid, the Bible is ridiculous. A Greek philosopher calls the Old Testament “utter trash.” Those were his exact words: utter trash! “Only a child would believe this nonsense; it’s the kind of thing an old woman would be embarrassed to sing to her child to get him to go to sleep; who would believe the story of Jonah and the whale? Man can’t survive in the belly of a fish. Who believes the story of god making the world in seven days?”

So there was an idea that Christians were stupid. What creates really huge problems is the Bible itself. When we think of the Bible today, it has that antique grandeur: the King James Bible and the way it’s translated, it feels so important and wise, every sentence feels so full, like ripe fruit, like there are centuries of literature in every sentence. But in those days what it felt like was badly written, often ill-thought-through nonsense.

And it felt like this to Christians, too. Saint Augustine gets very embarrassed by the Bible. Saint Jerome has nightmares where he’s accused by god of preferring classical literature to Christian literature. The problem is that the Bible is simple literature, and you can say today that this is a great virtue. But in the first days, it just seemed really stupid. It was written in a low-class Greek and low-class Latin, because often those writing it weren’t very well-educated. They would use the wrong words for things. It’s not that bad; it’s the equivalent in British English of saying sofa instead of settee or napkin instead of serviette. It’s just slightly lower-class forms of words. And they’d often get the grammar wrong; they’d get the cases in the Latin or the Greek wrong.

That is not a problem in and of itself, but it sort of is a problem if this was supposed to be the word of god. That’s what the Bible is supposed to be, the completely perfect word of god. But if it is, then god can’t do grammar very well.

CM: You write, “Many, many people are impelled by their Christian faith to do many, many good things. I know because I am an almost daily beneficiary of such goodness myself. This book is not intended as an attack on these people, and I hope they will not see it as such. But it is undeniable that there have been—that there still are—those who use monotheism and its weapons to terrible ends. Christianity is a greater and a stronger religion when it admits this and challenges it.”

What happens when Christianity doesn’t challenge it? What do you fear could happen to Christianity if Christians don’t realize the history of Christian destruction of the classical world?

CN: There are two things. One of them we mentioned earlier. We look at Islam and extremists within Islam and we think that it’s something specific to Islam. It’s not at all. That sort of thing happens in all religions, all the time. The main problem is that you see yourself as better. You see yourself as a fundamentally better human being, a cleverer one, a holier one, a smarter one, a generally better one than other people, simply from the fact that you’re Christian. And therefore you don’t check yourself so much. You don’t think, “Is that the right thing to do?” You start to treat other people less well.

The reason I thought of writing this book was that my father was a monk and my mother was a nun before they met. I was brought up in a fairly Catholic background. I remember talking to my parents about this, and they both said that a common way they would phrase sentences when they were at university was, “So and so is very nice, but not a Catholic.” That conjunction tells you everything. They thought to be nice and to be good you kind of had to be a Catholic, and if someone was nice and not a Catholic, it was weird. It was like an error of category to them. They were like, “How strange! People who aren’t Catholic can be good!”

They saw the world through a veil of religion, and it changed the way they saw other human beings: they rated them. They wouldn’t have said it like this, but they automatically rated other people as less good than themselves because they weren’t religious. That is so dangerous. Unless you know you’re doing it, you’re in danger of misusing that thought. And you’re also not understanding your own history. If you don’t understand your own history, how can you possibly begin to understand anyone else’s?

CM: Well, with that: thank you so much for being on our show.

CN: Thanks so much.

Featured image: watercolor by Emma Lu