Transcribed from the 28 July 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The environmental crisis is definitely a reflection of capitalism. Democracy is the instrument that we need to use in order to fight against that.

Chuck Mertz: A red-green revolution is on the rise, and it’s called ecosocialism. Here to tell us about it, Victor Wallis is author of Red-Green Revolution: The Politics and Technology of Ecosocialism.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Victor.

Victor Wallis: Thank you, Chuck, it’s a pleasure to be with you.

CM: You write, “Climate scientists are constantly finding that their dire projections pale in comparison with the actual pace at which life-sustaining natural infrastructures are breaking down.” How well suited is our current system of democratic capitalism, whatever you want to call it, for reacting to this kind of breakdown of life-sustaining infrastructures? How well suited are we, with this system that we have now, to address the problems of climate change?

VW: Capitalism is inherently anti-democratic, and it’s precisely because it’s anti-democratic that it’s not suited to solving these problems. In fact it’s created these problems. The system of capitalism is inherently defined in terms of the striving for growth and accumulation. That clashes head-on with the whole idea of natural limits, which are clearly being reached and have been even overtaken in many spheres.

Let’s say there is a democratic component to our life—it is one that has developed in defiance of and in opposition to the dominant interests of capital. It’s a reflection of popular movements over time, which have succeeded at certain points in introducing some measures that have improved the situation, as in the early seventies, when all the major environmental legislation was passed in this country. But it runs head-on into the obstacle of this perpetual desire for growth which now has reached an extreme form in the Trump administration: they are actively dismantling all the limited measures that were put in before to try and preserve something of the environment.

CM: Is climate change, in your opinion then, caused by a lack of democracy? Does climate change reveal to us the shortcomings of whatever we call democracy here in the US, or in the ‘Global North?’

VW: It’s a commentary not on democracy but on capitalism. Democracy is an ideal, or a technique, or a political message that would express (or does express as far as it can) the will of the people. But that has, from the beginning, been in conflict with the striving of the dominant class to maintain its position and to maintain economic activities. The environmental crisis is definitely a reflection of capitalism. Democracy is the instrument that we need to use in order to fight against that.

The democracy that is necessary for that purpose is much more sweeping and much more thoroughgoing than anything that we currently have in this country. Let’s say there are hints of it here or there. But the dominant parties that people have available to choose between, the Democrats and the Republicans, are not committed to the kinds of change that are necessary. In particular they are not committed to any effort to check the striving towards growth and accumulation which is touted and advanced by administrations of both the two parties.

Democracy cannot be merely a question of choosing between these two parties, but is a question of creating a popular movement that will permeate the whole society, transform institutions within the society, and create a new political force that can challenge both the dominant parties in this country.

CM: To what degree can democracy challenge, even conquer, capitalism? Are capitalism and democracy at loggerheads, and the confrontation they are going through right now is what leads to climate change?

VW: Capitalism and democracy have always been at loggerheads. It goes right back to the founding of the US and the constitution. There’s a famous Federalist Paper, number ten, where James Madison expressed his fear of a majority which would feel its strength and act in unison. There are many causes of climate change over geological time, but in the recent period of the last 150 years, and particularly the last fifty years, it’s been enormously accelerated by the burning of fossil fuels and the unlimited assault on the environment that has been the result of capitalist economic production.

We have to distinguish between producing for human need and producing for profit. Humans have existed on this planet without challenging the basic infrastructure for a long time. They’ve challenged it in small places, in limited regions there has been destruction and so on. But now with the globalization of capitalism, the threat to the environment is worldwide. There’s no place that’s immune from it, and the places that suffer from it the most are often not the places where the greatest amount of production and burning of fossil fuels is taking place.

But it has to be clear that democracy is a principle which fights against capitalism. I know that this is not what we’re instructed, but that’s part of the problem we have to overcome: people’s lack of awareness of the degree to which the lifestyle into which they’ve been accustomed, of constant acquisition and growth and measuring your well-being by material possessions, is at issue. We have to find ways of reshaping people’s sense of what we have to strive for. We have to satisfy people’s needs, but satisfy them on a basis different from individual privatized acquisition, and look to ways of satisfying people’s needs that place less of a burden on the environment. Not only less in the way of burning fossil fuels, but less in the way of production of toxins, using materials, and so on.

A large part of this reduction can be made by doing away with economic activities that don’t in themselves contribute to human well-being. I think first of all of military production. That’s a sphere of destruction. But there are many other aspects. The transit system is organized a certain way under capitalism, with the privatization of transit in the form of personal possession of huge vehicles and the resulting congestion—all these types of things have to be reconsidered. People can live as well—or, I would say, even better—without these threats to our health and to the long term stability of the environment.

This is going to become worse, and all the indicators are that the environmental dangers are accelerating, and they build on themselves in what they call feedback loops. We get gradual change for a long time, but at a certain point we get a sudden change.

CM: You write, “Tens of millions of refugees, desperate for a place to live, are fleeing sea level rise and flooded or storm-battered homes; others are fleeing wars precipitated by sustained drought-induced collapses of the food supply, as in Syria, Central Africa, Central America; still others are fleeing wars and repression that reflect longstanding imperialist projects but whose initiators have become ever more intransigent as they seek to ward off the prospect of a diminished resource base.”

How much is the migration crisis we’re seeing not only at the US-Mexico border but around the world driven by climate change? If we did not have climate change, would we have a migration crisis? Because the migration crisis is often depicted as being driven by politics or war, but I don’t hear climate change mentioned very often in the mainstream press.

VW: I think all of those factors are involved. It’s not one or the other, it’s a combination. But climate change is to some extent the cause of the wars. In the case of Syria, the uprising that started off that whole process was partly the result of a severe drought that took place across a five year period. It’s definitely a factor. And it’s going to become an increasing factor, especially as coastal areas get flooded—in countries like Bangladesh, it’ll be impossible for people to live. But even within countries like the United States, we’ve had the experience. What was hurricane Katrina? The coastal flooding was a result of the destruction of the protective areas that could have limited the flooding. There were internal refugees in the United States, you might say: 200,000 people who had to leave New Orleans and have never been able to go back.

It’s a straw in the wind, so to speak. This is going to become worse, and all the indicators are that the environmental dangers are accelerating, and they build on themselves in what they call feedback loops. We get gradual change for a long time, but at a certain point we get a sudden change: a sudden rise in the sea level, for example, or a sudden tsunami provoked by a big ice shelf dropping off, and so on.

We’re in the early stages, but it’s still affecting a lot of people very severely, even now already. The point is, it’s urgent. There’s still time, but it’s all a relative matter. There are certain changes that have already taken place, species loss and so on, but at least we can slow down the destructive process and try to create a better world in the course of doing so.

CM: What do we miss in our understanding of current events when we do not consider the changing climate’s role? Or worse, if we deny that there is climate change? What do we miss in our understanding of current events when we deny or dismiss the impact of climate change?

VW: Not just climate change but the entire environmental crisis: a lot of other things result from it, the toxins and petrochemicals, poisons, genetically modified organisms and so on. What we miss when we don’t take them into account is the whole agenda of pushing forward an economic drive without taking into account the actual needs of people. People have certain basic needs, like for decent housing. The homelessness crisis is terrible. The healthcare crisis is terrible. And the environment is linked with all these things. It’s linked with every aspect of human existence.

The biggest health problem is basically poverty. But poverty itself is something that reflects the local environment in which people live, which again is aggravated by these larger things as well. Understanding the environment is understanding the total context in which all our decisions are made. In order to resolve a problem in the environment, we have to be attacking all the other problems at the same time. The things that drive the environmental crisis are the same things that drive the housing crisis, the healthcare crisis, the drive towards war and so on. That’s where we come back to capitalism as the common source of all these things.

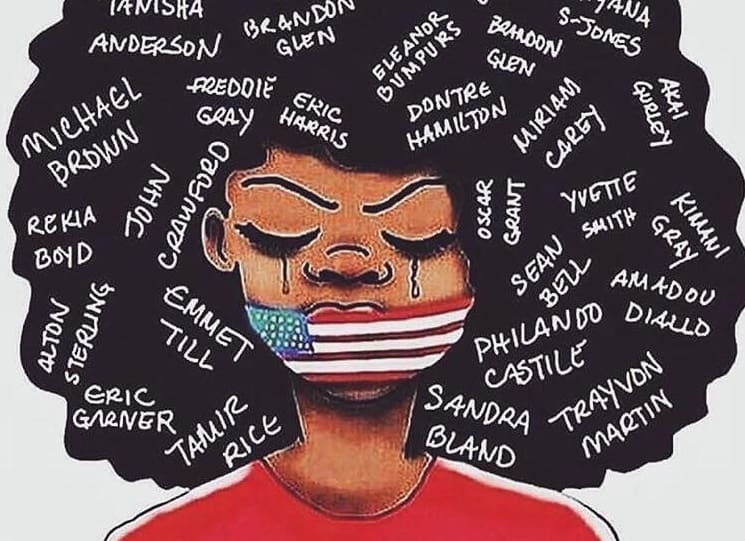

The challenge is how to understand all these issues in their combinations, in conjunction with each other: how do they relate to each other, and how in responding to them we could develop a unified program that covers all these issues. We have so many good progressive movements dealing with one or another of the particular issues, the particular types of oppression: racial oppression, gender oppression, the housing crisis, the health crisis. All these have to come together to form a cohesive political force to challenge the priorities of capital. The environment is an all-encompassing issue through which, when you study it, you can see how all these other issues fit in with it.

CM: You write, “While the top US mouthpiece of this ruling class mocks the reality of climate change, the military leaders who command the system’s armed enforcers have had no hesitation for at least the last fifteen years in publicly situating what they acknowledge to be the consequences of global warming: the droughts, floods, and hurricanes that directly or indirectly have pushed mass migration to its current extreme levels all are at the center of their concerns. The currently dominant forces, rather than join the fight against climate change, erect walls to block out its victims. By militarizing the problem, they not only draw resources away from any possible remedial steps, they also accelerate the spread of devastation.”

What happens when the public reaction to climate change is militarized? How does it lead to greater devastation?

VW: It’s not the public reaction that’s militarized, it’s the government that militarizes the situation by adopting a siege mentality. In other words, no serious person really denies that climate change is taking place. They may make a front of denying it. But they know damn well that it’s happening. The question is how do we respond to it? If you don’t want to make the changes that are necessary in order to address the issue, you adopt a siege mentality and say, “The world can go to hell, but I’m going to make sure that me and my family and my cohort are going to be okay: we’re going to erect barriers against intrusion, and we’re going to make our own private islands which will survive, so to speak, while everybody else is going down the drain.”

That’s what I mean by militarizing. You carry out land grabs, you make sure that you have your supply of fossil fuels and so on, and you intensify all of that. That becomes more intensified precisely as the crisis worsens. Because this group is protecting itself against a crisis which it can’t help but recognize is taking place. That’s the irony of the situation.

Denialism is a kind of political front to try and prevent people from taking the steps that are necessary in order to solve the problem. While they are doing this denial—this is why I mention the Pentagon—they are doing everything they can to make sure that those who count (in their eyes) are kept somehow protected from the effects of the production system that they’re on top of.

We have to challenge the priority of growth, so as to allow decisions—about what to produce, how to produce, and for whom—to be made on a different basis.

CM: You write, “The struggle to restore the soil and the struggle to create a just social order have up to now been carried on mostly as parallel political movements, without much mutual awareness let alone collaboration at the mass level. Such collaboration, however, or at least the striving to attain it, is the true centerpiece of red-green revolution.”

To what degree to we try to keep environmentalism and politics parallel instead of collaborative? After all, the right views environmentalism as liberal and leftwing. To what degree do you see environmentalism and politics as parallel instead of intersecting?

VW: The environmental movement has not been integrated into the other popular movements. This is part of the larger fragmentation of progressive movements in this country, which is a familiar problem. The challenge is that the environmental movement will only become effective when everybody sees it as part of their basic necessity. The environmental movement coming together within a really coherent force that would be constituted on a class basis is what will enable the majority of the people to become a political force.

This class basis is one of the central themes of my book. Nobody wants the Earth, the environment, to be destroyed. But the problem is that the capitalist class has an interest in blocking measures that would be needed to prevent that destruction. In that sense it is a class issue. Those who want to preserve the environment are forced to take measures which the capitalist class will resist to its dying day. This has been very well described, as in Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. She set it out very well. She pointed out that the capitalist class recognizes the changes needed as a threat to their existence as a class.

This is the key point that people have to take home with them. The fact that it hasn’t come together yet is partly the effect of the whole culture in which we live, which tries to pigeonhole different issues and keep people apart in various ways. Our task is to overcome those divisions and come together as a popular force so we can really challenge and eventually overcome this resistance.

CM: Is the essence of ecosocialism that all positions and policies are driven by their impact on the environment and climate change? Is the first question asked of every policy proposal and every decision whether this policy will adversely affect the environment?

VW: The general point is that the system as a whole blocks the measures that are needed to protect the environment. To challenge this we have to show how each issue is part of a larger position which challenges the basic priorities of dominant groups—the economic priorities of capital. These economic priorities affect every other issue. We can talk about how the housing market affects the problem of homelessness, or how privatization affects the problem of education, and this is parallel to the issues of how things affect the environment.

It’s not that we talk about every issue as an environmental issue, but we recognize the environment as an issue that affects everybody, and which displays the same structure of conflict. On one side, there’s capital pushing through privatization, maximizing production and so on, and it is indifferent to the human consequences. When there’s privatization of education, we let the majority be uneducated because that’s not their priority, and so on. With the real estate market, if it makes a lot of people homeless, they don’t care about it. Similarly with the environment: if it leads to a lot of toxins, if it creates health hazards and so on, they disregard that.

All these things have to be seen in their interaction, in that way. If people understand that, this will help them come together to form a cohesive political force which will challenge the dominant forces on all these fronts, not only the directly health-related things but housing and so on as well. The red part of Red-Green Revolution refers to the socialist tradition, the challenge to capital, and the green part refers to the environment—these really have to be understood as inseparable. Socialism challenges head-on the idea of putting unlimited growth at the forefront of the agenda. That’s the same position that’s taken by anyone who has to defend the natural environment. We have to challenge the priority of growth, so as to allow decisions—about what to produce, how to produce, and for whom—to be made on a different basis: on the basis of what’s in the common interest of all people. And looking at it long term, across generations, therefore taking into account the natural environment.

CM: Is there a relationship between what you see as a culture of violence and what you describe as a disconnect from nature? Does a culture of violence disconnect us from nature? Does our disconnect from nature lead to violence?

VW: Yes, there is a definite connection. The capitalist agenda is associated with domination of nature. Typically, the example is of the clear-cutting of a hill, removing all the trees: that’s a violent assault on nature. It’s similar if you want to get rid of factory fishing vessels which gobble up millions of little fish all at once—that’s an expression of violence too. Just as much as the propensity to go to war or the propensity on the part of individuals to go out and shoot a lot of people. There’s a connection between them all these things. They come out of a similar culture. It’s important to see that connection, to recognize all these issues as being interconnected.

This is a relationship with nature which sees nature as something to be contained, dominated, and controlled, instead of having natural structures or natural phenomena. The transformation of wild areas into golf courses is taming nature, dominating it, taking control of it and using a lot of chemicals to create an artificial environment. These things are all interconnected, and your question points directly at that insight.

CM: You write that what you believe is needed is a “cultural transformation, more provocatively envisioned as a transformation of human nature, which is an indispensable component of the ecosocialist project.”

A lot of people might think that transformation of human nature is impossible, that the idea of it is utopian. I believe that human nature transformed quickly between the 1930s New Deal state (that lasted through the War on Poverty) and the 1980s state of Reaganism (that has lasted until today as neoliberalism). Humans transformed relatively quickly and easily through policymaking.

Is transforming human nature easier than we think? Is it not as difficult to transform human nature as we imagine? For humans to adapt to the new nature that they live in, to one that is more concerned about our ecological impact on the planet? Is that a lot easier than we think it might be?

The idea that to live better is to have more and more is one of the fundamental things that has to be overcome and attacked, and this is not only for the sake of improving the environment but for its own sake as well.

VW: I don’t want to say that it’s easy, because especially at an individual level it appears daunting. But let’s just look at actual differences that exist and how they relate to practices that are carried out. One of the areas that I found striking, and really is an illustration of this, is the approach to imprisonment—punishment of people while they’re in prison, as opposed to rehabilitation. There’s a striking contrast between dominant US practices of not only imprisoning people but punishing them continuously and severely while they’re in prison, making it as unpleasant as possible, versus the practice in Scandinavian countries of seeing the prison experience as an opportunity to reeducate people. We could look at the difference in the percentage of people who go back out to commit crimes afterwards. There’s no comparison. It’s much, much smaller in those countries than it is in the United States.

That’s one illustration. But another point that we can make is in the psychological literature about raising children: when children are raised in an atmosphere of respect, they turn out differently from the way they turn out if they’re raised in an atmosphere of abuse. That’s pretty commonly recognized.

These are different kinds of human characteristics being displayed, and are clearly traceable to the formative influences on people. All we’re talking about when we talk about transforming human nature is such differences on a larger scale. If we have a cooperative environment, if we have a supportive environment, we will look at other people and treat other people differently from the way we would if we are in a constant ratrace against them and we see everyone as a rival or a competitor.

CM: You’ve been critical this morning of perpetual growth of the economy. What does ecosocialism offer as an alternative to a culture and politics of perpetual expansion? Aren’t expansion and growth the only ways we can have a good standard of living and also make our standard of living even better?

VW: We have to reconsider what we mean by standard of living. Do you measure standard of living by the amount of high tech goods that each of us possesses? I prefer the term “quality of life” to “standard of living.” Stardard of living is just a quantitative measurement in terms of goods. Quality of life refers to your actual health and the interactions you have with other people, your cultural experiences, and so on. The total material prerequisites for that are less, especially if you view it as a collective thing rather than as an individual thing. I mentioned the example of transit already, but that’s one illustration. The good life is something that involves sociality, the social experience of living in a community and of creating things with other people together. That type of thing is not something that involves a tremendous amount of material possessions.

There have been studies of the connection between happiness and material possessions. Of course if you’re deprived, you can’t be happy. Up to a certain point there is a real direct correlation between your material well being and your happiness. But when the material benefits go beyond that point, there’s no connection at all anymore. The connection disappears. People with enormous numbers of possessions can be just as mixed up and unhappy. It doesn’t benefit them anymore.

This idea that to live better is to have more and more is one of the fundamental things that has to be overcome and attacked, and this is not only for the sake of improving the environment but for its own sake as well, because we’ll actually be better off in that sense. We’ll be healthier. This is another point that some of these medical and public health studies have shown: great inequality is harmful to the health not only of the people at the bottom but even of the people at the top. It creates tensions and anxiety and constant fear and projection, which a inimical to a satisfied kind of life.

CM: You write, “The fusion of unabashed racism and misogyny with the ridiculous if not symptomatic concentration of wealth at the pinnacle of the US enforcement apparatus could galvanize the affected popular majorities, both in the US and worldwide, into a unity that many years of effort by activists have failed to achieve. Signs of such an impact are already spreading within the United States, as polls show increasing support for socialism among young people and as massive protests arise on the part of women, immigrants, low-wage workers, and prisoners, who in September 2016 launched a work stoppage across several states against the still-unfinished abolition of slavery. Such particular acts hint at a wider loss of legitimacy if the established order.”

I was going to ask you if we were on the verge of revolution, and if so when that revolution might happen. But since earlier you brought up the abrupt kinds of things that could lead to a quicker reaction, like an ice shelf breaking off and causing a tsunami: will the mobilization that we need be slow in coming, or do you think it might be as abrupt as climate change will be?

VW: Any revolutionary process, taken as a whole, involves both gradual components and sudden or rapid components. In a way, both are true. When revolutions come, they are sudden but they reflect a buildup over a long period of time. We’re seeing some of these first indicators of readiness for it, and that’s what we have to go on. What will it take to bring about a basic change? Every revolution seems impossible until it actually takes place. We know that from past history. Seemingly all-powerful regimes have been dislodged, have crumbled—but until they did, they seemed all-powerful. That’s something we have to keep in mind.

We have to keep struggling for what we think is right and needed, and we may even get some small improvements along the way, but we recognize that those are not enough. As we keep on doing this, that helps build up the support we need to form the kind of forces needed to really drastically change the conditions and the allocation of power in society, and make it into a democratic power which is collectively held by the majority of the people, through real representatives, people who actually come form the background of wanting these radical changes, and who will therefore not betray that when they get into positions of office. But that requires an organized force and not just individual politicians. There may be individual politicians who are sincere and committed; there will be limits to what they can do. They need more of an organized force.

So this is a combination of gradual and sudden change. Sorry to weasel on that one.

CM: Victor, I really appreciate you being on the show this week.

VW: Thank you very much, Chuck.

Featured image: Rice farming in Kerala, where there is on ongoing, massive and successful self-organized effort by smallholder farmers to reclaim and cooperativize land stewardship and food production