Transcribed from the 4 August 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

These liberationists were saying that theology is always political, and that it served as a prop for the political system, that it served as a prop for the economic system. They were saying theology has to be re-created so it doesn’t provide legitimation for these oppressive systems.

Chuck Mertz: Liberation theology challenges the contradiction between the rhetorical embrace of freedom in the US, while the US puts limits on those very freedoms. Here to give us a history and tour of liberation theology: historian, women and gender consultant, speaker, cultural critic on social justice, and—the greatest descriptor ever—feral theologian Lilian Calles Barger is author of The World Come of Age: An Intellectual History of Liberation Theology.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Lilian.

Lilian Calles Barger: Thank you for having me.

CM: For those who don’t know, what is liberation theology?

LB: Many people don’t know what it is. I will give you my definition, a layman’s definition. Liberation theology is a radical and religiously-motivated intellectual and social movement that swept the Americas in the 1960s and 70s. They had some very strong critiques of theology and religion in the 1960s with all the turmoil that was going on, and their legacy is still with us. People throw the term around, and one of the reasons I wrote the book was to clarify for people where it came from, what it was really about, and what it was trying to do.

CM: How much do you think the legacy of liberation theology was the rise of more socialist-leaning governments throughout Latin America in the earlier part of this century?

LB: We have to go back to the United States’ intervention in Latin America that really instigated it. The United States was very instrumental in setting up dictatorships and suppressing dissent in Latin America. Part of the response of Latin American theologians, the liberationists, was really a critique against US power in Latin America.

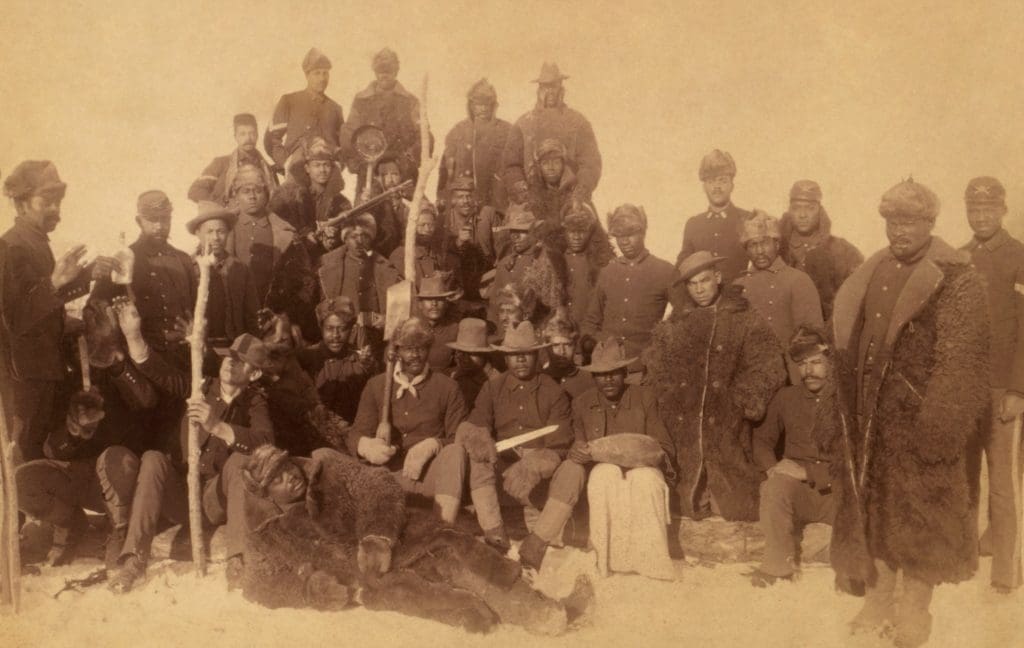

They were very much involved in the social movements, labor movements, and movements for poor people. But liberation theology is not just Latin America—it’s not just about Catholics, and it’s not just about Latin America. There were also protestant theologians, from a variety of different denominations, who joined the Catholic theologians in constructing a liberation theology for Latin America. And there were also strands of liberation theology in the United States, one that came out of Black Power, one that came out of women’s liberation—a feminist liberation theology and a black liberation theology. All three of these theologies have something in common, things that bring them together—and there are reasons why they never really congealed into one movement, but they are still very much alike.

CM: We speak a lot about black liberation on our show. Why do you think Marx comes up so often within these liberation theologies—whether it’s Latin American liberation theology, African-American liberation theology here in the United States, or feminist liberation theology? Why do you think they so often find Marx as an inspiration?

LB: Because of Marx’s view of the caste system—that’s particularly true of Latin America. James Cone, who recently died (on 28 April 2018), was late to coming into really using Marxist analysis. Also, there was feminist Rosemary Radford Ruether—though I would say she and James Cone were really talking from a socialist perspective, not so much a Marxist one.

But they did use it; a lot of people use Marxist analysis. It’s useful. It’s helpful. It does provide a certain degree of analysis about why the economic situation is the way it is and why discrimination is happening, and of ideology. These liberationists were saying that theology is always political, and that it served as a prop for the political system, that it served as a prop for the economic system. They were saying theology has to be re-created so it doesn’t provide legitimation for these oppressive systems.

CM: What do critics of any of the liberation theologies—whether related to women or African-Americans or to Latin America—miss in their understanding of liberation when they dismiss any of these liberation theologies or any of these fights for liberation simply because they use Marx as a touchstone, and then dismiss them as Marxist or communist or socialist in some way?

LB: Part of what they miss is that liberation theologians’ emphasis was on this world. A lot of theology—and this is one of their critiques—is centered on transcendence, on the otherworldly, on these abstract concepts. They said this is not where people are: people are struggling—and we want to redefine god. God is with the struggle; god is among the oppressed. He’s among black people—god is the god of black power. God is the god of women’s liberation. This instead of putting god in some sort of abstracted otherworldly category.

Part of the criticism of liberation theology is that they were too concerned (to the exclusion of otherworldly rewards) with the political, that they were too political. They said no, we’re not too political—you’re political too! You just don’t acknowledge your politics. You won’t acknowledge the fact that in your theology is already a political assumption about the relationship of Christianity (for instance) to the liberal state.

CM: That’s the next question I was going to ask you: whether the church would oppose the politicization of their religion. Because the church is clearly politicized. It has been since, I believe, right around two thousand years ago. So by definition, liberation theology—I looked it up online—is a movement in Christian theology developed mainly by Latin American Roman Catholics that emphasizes liberation from social, political, and economic oppression as an anticipation of ultimate salvation.

Does that in any way challenge the religious beliefs of either the Catholic church or Protestantism?

LB: When you read liberationists, they don’t spend a whole lot of time dealing with dogma of the explicitly religious kind—how does salvation occur, and atonement, and all kinds of abstract things. They don’t really deal with that. They’re very concerned with living out the message of Jesus; they are interested in a prophetic theology that addresses the real needs of people, and they don’t get too concerned with dogma. They don’t even really attract much attention to it.

The poor and the oppressed and the people who have been downtrodden throughout modern history have a theology. It was never recognized. And if you listen to what they say, the god that they talk about is very different from the god of white, elite males.

That’s one of the issues: a lot of theologians say they’re really not theologians. They weren’t really doing theology, they were just doing cultural critique or ideological critique, but they weren’t really theologians.

But I believe they were, that they are theologians.

CM: Is the church’s opposition to liberation theology an anti-revolutionary policy? That is, no matter who is in charge they are trying to be somehow objective, neutral, parallel to politics, or at the very least deferring to the status quo? Was part of it that they didn’t like Roman Catholic priests or even protestant preachers telling people that we need to make a change—that this could be leading to a revolution? Was that the problem that the church had?

LB: Absolutely. That really goes back to the Reformation—and the Enlightenment, which was really an accommodation between the church and the state. The church said to the state, “Okay, you take care of all the issues of this world, and we will take care of people’s souls for the next world, and we will not really interfere in the liberal political situation. We’re just going to deal with people’s individual salvation.”

This consensus, this agreement, this collusion was very detrimental to oppressed people. Because the liberal state could oppress people, and the church would say to them: “Yeah, you’re a slave in this world, but you will be free in the next.” Or, “Yeah, you’re suffering under this liberal state, but you are free spiritually.” Liberationist theologians had a huge objection to that. The idea that when somebody is in economic and political bondage, you would tell them that they can be spiritually free—they did not accept that.

When I say church, I say it very broadly—to include not just the Catholic church but all the protestant churches that came out of the reformation. The churches had pretty much given up on the political in certain ways. In the United States, the US state is a “good state,” it’s a “Christian state” and we’re just going to leave it alone, and the suffering that’s going on, well, we’re going to depend on private charity and we’re going to make sure people understand that they have a reward in heaven for their suffering.

CM: You write, “Since the 1960s, Gustavo Gutierrez had been advocating for a new theological method, one that would take as its starting point the perspective of the poor and the marginalized.” Is that liberation theology’s most overriding feature, whether it’s in Latin America, whether it’s in African-American or feminist liberation theology? To help the poor from the perspective of the poor and the way the poor want to be helped, because the poor know what’s best for the poor?

LB: If you think about it, most Christian theology has been done by white elite men in very elite situations. What the liberationists were saying was that because they’re reading the Bible from their elite perspective, their white male perspective, and their perspective of affluence, they are reading it for what they need to get out of it. They argue, rather, that you have to let poor people, women, black people read the Bible and tell us what god is saying in the scriptures–that they have a theology too, though it’s not recognized. The poor and the oppressed and the people who have been downtrodden throughout modern history have a theology. It was never recognized. And if you listen to what they say, the god that they talk about is very different from the god of white, elite males.

CM: You write, “This controversy isn’t about helping the poor or not helping the poor, but about how best to advocate for social justice. The archbishop of Buenos Aires, the future Pope, had worked tirelessly for the poor while rejecting liberation theology.”

So how does Pope Francis’s idea of social justice differ from the idea of social justice within liberation theology?

LB: Catholic social teaching has always been concerned with the poor. When Pope Francis is talking about the poor in a fresh way, he’s really revitalizing a longstanding Catholic social teaching that goes back to the late nineteenth century. So he’s not “becoming a liberationist.” The difference—and this is what liberation theologians would critique—is how dependent upon charitable people it is, people with means who want to help the poor and are charitably-minded and sympathetic. They’re saying that’s not enough. It’s not just a matter of helping the poor or being nice to poor people. It’s about sharing power. It’s about listening to what they say and also amplifying their voice. Basically, they are the subjects of their own liberation, the subjects of their own freedom, instead of thinking that they have to wait for people to come and be nice to them.

The difference between liberation theology and Catholic social teaching, as the liberationists proposed it, was who is the one that is doing the liberating. Are oppressed people liberating themselves? Or are they waiting for someone of goodwill to come and help them?

CM: You describe how “Many on the right, both Catholic and non-Catholic, heard the Pope as advancing liberalism at best and communism at worst. United States observers such as Rush Limbaugh, the conservative talk show host, called his exhortations ‘pure Marxism.’”

Is the degree to which the Pope is a Marxist exaggerated not only by the right but by the left? That is, how much does even the left exaggerate Pope Francis’s “left-ness”?

LB: It’s absolutely exaggerated on both sides. They’re both wrong. Pope Francis is a revitalization of traditional Catholic social teaching. Back when he was the bishop in Buenos Aires, he was accused of actually being against liberation theology and putting out stumbling blocks and trying to prevent it. But at the same time, he was working for the poor, as you stated before.

He is also a very pastoral Pope. He wants to heal the divisions within the Catholic church. And liberation theology over the last forty or fifty years has been one of the major divisions within the Catholic church, because it was rejected by the Vatican very early and was basically excommunicated, completely rejected. Francis was the first Pope to say, “Wait a minute, I want to talk to Gustavo Gutierrez.” That’s a pastoral welcome, trying to build bridges.

That’s how we need to understand Francis instead of thinking of him as either a Marxist or a liberationist. It doesn’t work. That’s not who he is.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer said we needed a god who would suffer with people. He said we needed a crucified god, a god who was with people in the world—and that otherwise religion was irrelevant. People didn’t need religion, people didn’t need a god to explain the world, because we were finding out what the world was about. We needed a god that could alleviate suffering.

CM: If liberation theology demarcates a divide within the Catholic church (or whatever church), can we take that to the next step? Do our differing views about liberation—is that what divides all of our politics? Is that the real line of demarcation within politics even outside of the church?

LB: Well, today of course we have a religious right (it really came into being in the late seventies, and was in full force in the 1980s), and then we have a religious left. It’s almost like there’s a new war of religion going on in the United States between different interpretations of what Christianity means, what it means to be a person of faith, what the social implications of that are. The right would say that the social implications of their faith would be to limit abortion rights, to abolish gay marriage; they have a certain view of how society should be structured. And the religious left also has a vision of how society should be structured that is different from that. It’s about having equality for all people and justice for all people, whether they’re gay or whether they’re black or women or whoever.

It’s not just a political split in the country—there is a deep religious split in the country. You can’t split politics from religion. It’s always entangled.

I don’t know how this split is going to get resolved. But we are no longer a country where a religious people can just be sequestered in their churches and practice their private religion. Religion is in the political realm. It was always political in its own way, but now it’s full throttle out in the political arena.

CM: If liberation theology, then, got rid of that sense that politics and religion should be parallel, how much did liberation theology—whether it intended to or not—create the environment, create the kind of thinking, blur those lines that led to things like, let’s say, the Moral Majority in the 1980s?

LB: It’s definitely there. The Moral Majority and the religious right had some intellectual thinkers and some theologians behind them, like Carl Henry, who really changed their position on how they believed their people, their evangelical fundamentalist groups, were to relate to the political. They basically believed that the United States was a good nation, a liberal nation—it’s fine, leave it alone, it was founded on Christian principles, and all we need to do is go out and save individual souls for eternal salvation. They did believe in doing good things too—yes, you help poor people—but they didn’t believe in social justice in terms of the state establishing social reforms.

But they changed their view about politics. They went from staying in their churches and trying to save people—if we change hearts we can change the nation—to going into the public sphere and advocating for a social vision. That was a deep change in evangelical theology that hasn’t really been explored. I just barely touched on it in my book. But it was a theological change—it wasn’t just a political change. They had to change how they saw themselves as believers, as people of faith, in relationship with the political.

They were also responding to the same things that liberationists were responding to. The Christian right was very afraid of black power, and what was going on with the radicalization of women. And theologies were emerging in those areas. They thought, “We’ve got to get in there and advocate for our social vision,” where before they hadn’t really had one. But all of the sudden, abortion got on their agenda. Marriage and family and all kinds of things got on the agenda that had never been there before.

CM: You write, “In the 1960s and 1970s, during a few short years, Latin Americans and North Americans, Catholics and protestants, black and white, men and women participated in an intense discussion among themselves and with their detractors about how theology was to facilitate the immediate struggle for human liberation. What they shared in their trans-American conversation was a set of grievances against the theological establishment, which was dominated by white North American and European men, on behalf of the oppressed in the Americas.”

Is liberation theology, then, a challenge to white privilege, even white supremacy? How much of a role do you think challenging white supremacy or privilege played in liberation theology being condemned by church elders?

LB: Absolutely, yes. It’s against misogyny, it’s against white privilege, it’s against a class system, neoliberalism. It’s against all those things. And yes, that’s one of the reasons it was rejected. It was called racist, or accused of ignoring the differences between men and women, and attacking the economic freedom of rich people. So that’s exactly the reason why, and it’s a political reason. There were theological reasons too, but the political reason liberation theology was rejected and not ever given a fair hearing was very strong.

The liberationists basically said it’s an ideological reasoning that theology is backing up. It’s ideological. And they didn’t deny being ideological themselves. They said: “We know that our theology is political, but so is yours.”

CM: You write, “Through science, technology, and humanistic inquiry, a German theologian by the name of Dietrich Bonhoeffer pointed out that the world was gaining mastery over previous mysteries and no longer needed the working hypothesis called ‘god.’ This new world of human mastery reflected what he called a ‘world come of age,’ responsible for itself without recourse to a god far removed from the world.”

Does liberation theology, then, argue that through science, technology and humanistic inquiry, we have become disconnected from religion, and when you are disconnected from religion there is a greater likelihood you become disconnected from the needs of the suffering?

Unless you can appeal to that religious motivation, the impulse that people have to their ‘ultimate concern,’ you cannot mobilize enough people to change society and to have the kind of social revolution that many people want on the left.

LB: Bonhoeffer wrote during World War Two. He was in prison; he had prison diaries. He was saying that the world was at a point where people were living like they really didn’t need god anymore, because the god that had been offered people was a very transcendent god, the “god of the gaps,” the god that offered the explanation for all the stuff we can’t explain. But the more things we can explain, the less we need god. We have science, and we have humanistic inquiry, and we have other social sciences explaining things for us; why do we need god to explain the unexplainable?

He said what the world needed now was not a god that filled the gaps, a god that is the last explanation for things that could not be explained; what we needed was a god who would suffer with people. He said we needed a crucified god, a god who was with people in the world—and that otherwise religion was irrelevant. People didn’t need religion, people didn’t need a god to explain the world, because we were finding out what the world was about. We needed a god that could alleviate suffering.

CM: How do we view black, Latin American, and feminist liberation theologies differently, when we view them as a whole, as one larger liberation movement?

LB: I try to show the affinities. These three movements tried to get together in 1975 in Detroit, and figure out what they had in common and what they could collaborate on—whether there was some way to create a coalition. That fell apart, because the black theologians were saying that the most important thing on the table was race, and the Latin Americans were saying that the most important thing on the table is class, and the women were saying, no, it’s gender and sex.

Because each of them had their most important thing that they were advocating for, they could never really get together and form a cohesive coalition. What could have been a very unified movement really fractured and fragmented, and each of those theologies went their own way.

Let’s look at all these theologies, and look at how can we try to bring them back together, and how we overcome the division around what’s “most important,” race or class or gender, and realize that it’s about oppression generally. People are oppressed in multiple ways. It’s an intersectionality of oppression. You’re never just oppressed for one thing. It’s always multiple things at play. If you’re a black woman, it’s not only that you’re a woman but that you’re black. If you’re a poor black woman, you’ve got three things going on there.

So the intellectual movement really splintered. Our coalition politics in the United States have not worked very effectively at bringing a lot of different groups together. It’s very difficult to bring people with different interests—people who hold different things as the most important things—together to collaborate and cooperate together to build something that helps everybody.

CM: You write, “From 1980 to the early decades of the new millennium, black and feminist theology produced a second and third generation of politically committed theologians and extended the reach of their ideas by applying their theological method to new situations.” You point out that that has had a resurgence with the Black Lives Matter movement.

But to what extent has liberation theology always provided the alternative to neoliberalism? They’ve always said there is no alternative. To what degree has liberation theology always been providing that alternative from the outset?

LB: It always has been the alternative.

But in the nineties, liberation theology was written off. Because there was so much prosperity in the nineties, people thought we don’t need that. If we go with Reagan, if we grow the economy, get trickle down economics and all that, we don’t need to worry about the poor, it’s going to solve itself. That’s one thing.

Liberation theology, because it’s an intellectual, religious, and political movement, declined along with the decline of radicalism in America in the late twentieth century. But it was still there. It was being exported, it was going all over the world. There is South African liberation theology, there is Palestinian liberation theology, there is liberation theology in India and Korea. It got exported from the Americas. It also got spread with gay liberation theology, animal liberation theology. There has been a huge number of different groups—sexual minorities, for instance, or Chicano and other groups—who have taken up liberation theology.

So in those years where it seemed like it was retreating, it was actually spreading and growing underground. Then we got into this century—and now on top of everything we’ve got Donald Trump in the white house, which makes the left and progressives very alarmed about inequality growing exponentially, and liberation theology is now experiencing a resurgence. It’s an amazing tool to revitalize social movements.

If we look at the history of social movements in the United States, every one of them, from back in the nineteenth century with abolitionist and women’s movements and civil rights, they were always undergirded by strong radical religious theology that went with it. It was never the majority of the churches. Abolitionists were not the majority. Neither was women’s rights or civil rights. But those movements themselves always had a religious underpinning. And today we’re not going to be successful in our social movements unless we revitalize theological and religious views that could undergird those movements.

CM: How important is the role of religion in revolution and its level of success in challenging the state and the status quo? Can we have revolution without religious guidance or reinforcement or confirmation?

LB: You cannot get people to really commit to a social movement unless you appeal to what the theologian Paul Tillich called “their ultimate concern.” The polls show seventy to eighty percent of people in this country still believe in god. Even if people are not associated with religious institutions, whether or not they’re going to church or synagogue or wherever, people have a very strong sense that there is something more than just what we see. Unless you can appeal to that religious motivation, the impulse that people have to their ‘ultimate concern,’ you cannot mobilize enough people to change society and to have the kind of social revolution that many people want on the left.

You have to be able to talk to the people who are sitting in church pews, and the people who are not sitting in church pews but still have a very strong sense of religion. You have to find that connection. What are the connections between your social justice movement and people’s religious impulse?

CM: Thank you so much for being on the show this week, Lilian.

LB: Thank you, Chuck.