Transcribed from the 6 October 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Of course these institutions are hand-tied and captured and can’t be relied upon to get us beyond their own shortcomings.

Chuck Mertz: This moment is not merely a moment. It is not just a blip. We can’t just wait and all these crises we face will simply go away. Except that’s what liberalism wants us to believe—to not consider that we may be facing a more systemic and permanent failure. Here to help us understand why it’s all liberalism’s fault, live from Brooklyn, writer Aaron Timms posted the Baffler article “This Is Not a Blip: What’s wrong with what liberals say is wrong with the world.”

Welcome to This is Hell!, Aaron.

Aaron Timms: Thank you for having me.

CM: I’m going to read a little excerpt here so people will understand the context of our discussion. You quote David Lipton, the second in command at the International Monetary Fund, saying on current challenges to multilateralism: “Times have changed. We live in an era of doubts and questions about the global order. We are in a true recession of trust. But trust can be rebuilt. We can restore trust in institutions and larger purposes if we set out to regain the sense that something concrete can be achieved by working together.”

But to you, “Something about Lipton’s words stuck with me. Since this moment is just a moment, as Lipton implied, it’s fair to assume that the conditions that have brought it into being are temporary, a deviation from a norm that we can all be assured will return as the dominant theme of human endeavor. For Lipton, as for many others in the political and policy establishment, the way out of this ‘recession’ is by finding the path back to the ancien régime. The way that multilateralists regain public trust in multilateralism is to continue being multilateralist. The answer to bad institutions is institutions. The woes besetting the global liberal order call not for less but more of the global liberal order. We have diagnosed the disease, and its cure, apparently, will be its cause.”

Last week we were talking with Adam Kotsko, author of Neoliberalism’s Demons, and Adam pointed to the self-legitimating nature of neoliberalism. That brings me to a larger point here. Do you see a similar form of self-legitimation within liberalism as well? Or is that simply a common component in all political ideologies, that they are all to some extent self-legitimating?

AT: They probably are. It’s a battle over defining the rules of the game and making sure that any deviation from the rules of the game is corrected by adhering to those rules. That’s what came across in the speech that David Lipton gave. David Lipton is not a well-known figure—he’s pretty obscure. But he’s exactly the kind of faceless technocrat who thrives in institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, the institutions of the EU, the institutions and agencies of the US government, even places like the US supreme court. We’re not that well acquainted with the people who make their way into these institutions, but when they do come out, we get interventions like Liptons, which is all about insisting on the rules of the game and not questioning the premises and preconceptions that underlie those rules.

It is self-legitimating in the sense that we can’t question the underlying system. All we can do is reinforce the rules as sound. That’s the automatic response we get to any moment of crisis: “Well, this is a moment, this is an aberration, this is a parenthesis, this is exceptional, it’s unprecedented, it’s extraordinary.” These are words used over and over again by liberals to describe the emergence of populism broadly understood. But because it’s so extraordinary, because it’s so unprecedented, because it’s so exceptional, we have to respond to this exception to the rules of the game by enforcing and obeying and observing those rules, and reinforcing their legitimacy.

There is a basic question of legitimacy that’s at the core of all of this. We saw it again this week when we were disabused of thinking that the FBI was going to be a panacea to this horrible nominee to the supreme court—of course these institutions are hand-tied and captured and can’t be relied upon to get us beyond their own shortcomings. Literally the response to a bad institutional choice, a bad nominee to the supreme court, was to reinforce the primacy of institutions. That’s what liberals thought was going to get us out of this mess. Of course it’s only made things worse.

CM: You write, “Emanuel Macron told an audience of world leaders earlier this year that we are living through ‘a moment where trust is shaken.’” We’re being reassured that this moment is not permanent. But how long has this moment of crisis, in your opinion, been going on? How long has this “blip” been going on?

AT: In the eyes of liberals, it’s a break. There are events that capture what is abhorrent to them, it’s like their taste is offended by what’s going on. But the blip, really, is not a blip. It’s a long term function of the way that liberalism has evolved over the course of decades.

It’s really a postwar phenomenon. The origins of neoliberalism with the Mont Pelerin society and places like that involved ‘encasing’ the market (to use the term that Quinn Slobodian uses in his excellent new book) and protecting it from the unruly forces of democracy. From there we’ve seen an evolution and institutionalization of that approach to the market and to liberalism generally: it accelerated through the seventies and eighties with financialization and a number of other bad policy choices that were made—again to protect the market from the difficult demands of the people.

What we’ve seen over the last few years with these events that are so repellent to liberals—Brexit, Trump, the rise of populism (as broadly understood and poorly defined) in Europe and Asia and elsewhere, the revenge of the people—is a reassertion of the primacy of democracy, a coupling between liberalism and democracy.

When did it start? It started a long time ago. The problem is not Donald Trump. The problem is not Brexit. The problem is not Duterte in the Philippines. The problem is this system that we’re saddled with and the compromised marriage between liberalism (which doesn’t want to have to deal with people and their real concerns and worries) and democracy (which is the pressure valve that allows them to express those worries and concerns). It’s very much a long term process.

The financial crisis happened, and that was really bad, and people got really pissed off, and then we got Trump. That’s as deep as the historiography of the blip goes. But there were policy choices that were made in the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties which led to the crisis.

The blip, broadly understood, is not a blip, it’s a process—it’s a feature of the system, not a bug. But liberals try to present it as a bug, and use that as the basis upon which to say this is just a moment that’s going to pass. It’s difficult, but it’s like having a cold; you just have to ride it out and we’ll get back to business as usual. We’ll go back to whatever it was before Trump came to power—which in the US was rampant financialization of the economy and all sorts of other bad things.

It’s a long term process. Liberals misdiagnose a broken system as just a momentary bug.

CM: I want to get to why they misdiagnose it. You write, “Sociologist Greta R. Krippner has shown financialization of the US economy was the policymakers’ response to distributional conflicts triggered by inflation in the late 1960s and 1970s. Deregulation was a way of letting the market, rather than government, decide how to distribute capital among competing actors.” You also talk about how credit was opened up, and how debt fueled the bounce-back of the economy after the sixties and seventies.

So how much is our refusal to recognize that this is more than a blip based on our unwillingness to hold president Reagan and president Clinton accountable? Republicans believe in the myth of Reagan’s economics policy prowess, and Democrats believe in the same myth about Clinton, and we refuse to reconsider financialization and market deregulation, because both sides, politically, embraced it and refuse to admit that their hero made a horrible mistake which has led to the rise of the far right.

AT: Frankly it’s even president Carter: a lot of this started in the late seventies. That’s a huge component, this blindness to history and an unwillingness to examine exactly what happened. Instead there’s this idea of the Reagan years as a golden era, and the Democrats’ idea of the Clinton years as an era of unrivaled prosperity where liberal democracy was spreading throughout the world and it was the End of History.

This idea that the eighties and the nineties were great—we, the West, collectively defeated Communism, the economy was growing (broadly speaking), things were good, the president was jogging, everyone was happy, the only thing we had to worry about was a sex scandal. This blindness to what actually happened and this failure to see the problems that we’re confronting today as being fundamentally anchored in the choices that were made on both sides of politics in the eighties and nineties is a huge component.

Samuel Moyn had a really interesting piece in the Boston Review this morning about the “juristocracy” and how our response (progressives or people on the left, if you like) to the Kavanaugh nomination should not be to try and stack the court again, it should be to examine the court’s position in the governmental architecture of the country and to reexamine the cult of constitutionalism.

That’s basically a variant on the argument that you’re suggesting, which is that we need to be much better historians. We need to think much more carefully about the origins of these things. The ideology of the ‘blip’ that liberals talk about—in other words, the examination of the causes of the blip—is always really superficial. Blip-thinkers, as I call them (liberals with a furrowed brow about the rise of populism), don’t like to look back very far when they’re thinking about what the causes of this moment actually are.

I argue for a much more searching examination of those causes. They say, “Well, there was a financial crisis.” That’s about as far back as they go. The financial crisis happened, and that was really bad, and people got really pissed off, and then we got Trump. That’s as deep as the historiography of the blip goes. But there were policy choices that were made in the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties which led to the crisis, and we have to think a lot more carefully about what those choices were and what could have been done differently to avoid that kind of situation.

It’s also much more comprehensive than that. We have to think much more carefully about the system, broadly understood, and whether this system is in any way equipped to get us out of this situation. I definitely don’t think it is.

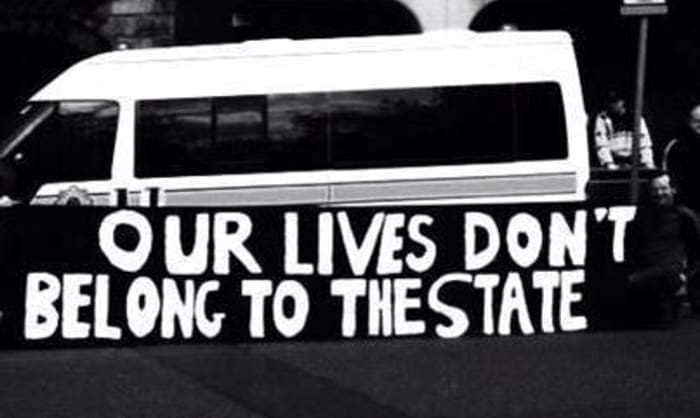

This isn’t the system that we should be functioning under, and we should think about a different vision of economic and civic life, and a different version of human potential and the ways to unlock it and allow it to flourish.

CM: I want to make sure people don’t have confusion about what liberalism is, because of different definitions in global politics as opposed to here in the US. You write, “The situation today is not the parenthesis of progress, but its product. This is what is truly deranging about blip thinking. By mistaking entropy for a fleeting moment of collective madness, it ensures the political establishment’s comfort in doing nothing to address the real problems besetting the world today. It is a call for only the most superficial form of action—which is to say, inaction.”

Which brings us to an article in last week’s Washington Post, co-written by past guest on our show Chris Mooney, that reports, “Deep in a five-hundred-page environmental impact statement published in August, the Trump administration made a startling assumption: on its current course, the planet will warm a disastrous seven degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century. A rise of seven degrees Fahrenheit (or about four degrees Celsius) compared with pre-industrial levels would be catastrophic, according to scientists. Many coral reefs would dissolve in increasingly acidic oceans; parts of Manhattan and Miami would be underwater without costly coastal defenses; extreme heatwaves would routinely smother large parts of the planet. The world would have to make deep cuts in carbon emissions to avoid this drastic warming, the analysis states, and—quoting the statement—that would ‘require substantial increases in technology, innovation, and adoption compared to today’s levels and would require the economy and the vehicle fleet to move away from the use of fossil fuels, which is not currently technologically feasible or economically feasible.’”

Is Trump, and his environmental policy of not doing anything because “nothing can be done, it’s already too late”—is that a sign that he is, more than anything, a supporter of the liberal status quo?

AT: He wouldn’t cast it in those terms. But yeah. When I say liberalism I mean it in the classical political philosophy sense of the term, rather than liberals being people who are to the left of center generally or people who don’t like Brett Kavanaugh.

Obviously Trump is a function of the liberal order. That’s a point that hovers over the top of everything. He’s basically a worse-dressed version of the liberal blip-thinker. He arrives at a lot of the same policy outcomes that they do, it’s just that he doesn’t dress it up as nicely and he’s not as well spoken and palatable.

This idea that we can’t do anything about the environment—they don’t want to do anything about the environment, of course—is not quite the same as blip thinking, but it’s definitely of a piece with the way that liberals are responding to this moment. Of course, the liberal will want to say that climate change is bad and we should do something about it—a position I personally agree with, of course—but the institutional machinery that you have to grind through to “get stuff done” is what the liberals will insist on as a response to this moment of crisis. The response to climate change is to seek change through institutions rather than examining at a deeper level what it is that has forced the climate to change and has brought us into this era of anthropogenic climate change.

Trump’s response is that he really only cares about the lobby groups that he answers to—or doesn’t even answer to but dictates to—and as we all know, Trump doesn’t really care about anything other than himself. He doesn’t really care and he’ll do nothing about climate change just to own the libs. But ultimately they’re going to get to the same endpoint, which is to do not very much. To wash their hands of the whole thing and say, “Well, it’s all just a bit too hard. This is really difficult, but this is just the world as it is, and this stuff is happening and it’s sad, but there you go.”

CM: You mentioned the disconnect between democracy and capitalism; we have this idea of giving all people equal opportunity to become rich, to get all the things that they want, equality of wealth, of opportunity, of self-worth, but capitalism is based on competition among individuals against each other, not everybody having wealth. It’s not about raising all boats, it’s about raising one boat way up high and a bunch of other boats barely floating, and then there’s the other ones at the bottom of the ocean.

To you, what explains this disconnect between our understanding of democracy as something that is about opportunity for all, and then employing an economic system that is not about opportunity for all? Why do we have that disconnect here in the United States?

AT: Ignorance is probably the main thing, ignorance about what capitalism actually is and what it’s designed to achieve. If we were a bit more honest with ourselves about what this system is, what it’s designed to produce, what its origins are, and how it evolved, then we would come to a much more honest, frank, and helpful appreciation of the situation that we’re in. We would see that actually, maybe this isn’t the system that we should be functioning under, and we should think about a different vision of economic and civic life, and a different version of human potential and the ways to unlock it and allow it to flourish.

CM: Well that seems simple enough. Aaron, I really appreciate you being on our show this week. Thank you so much.

AT: Thank you.

AntiNote: Editing this interview transcript with some hindsight—in March 2022—was quite the experience.