Transcribed from the 22 September 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The psychiatric assault on anti-authoritarians is only one spoke in the wheel. There is a criminalization of anti-authoritarians. Anti-authoritarians get marginalized on many levels—financially as well. All kinds of things happen to them.

Chuck Mertz: In the US, we view anti-authoritarianism as an illness to be treated with drugs. That’s not a good thing, if you want to avoid living in an authoritarian, dystopian future. Here to guide us through authoritarianism and anti-authoritarianism, practicing clinical psychologist Bruce E. Levine is author of Resisting Illegitimate Authority: A Thinking Person’s Guide to Being an Authoritarian – Strategies, Tools, and Models.

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Bruce.

Bruce E. Levine: Great to be back on, Chuck.

CM: You write, “Authoritarianism is routinely defined as relating to or favoring blind submission to authority. In contrast, anti-authoritarians reject—for themselves and others—an unquestioning obedience to authority, and they believe in challenging and resisting illegitimate authority.”

Is acquiescing, then, to any level of authority the endorsement of and support of authoritarianism? And conversely, to be anti-authoritarian, do we need to deny all authority? I’m trying to figure out if there are degrees within authoritarianism. What does it mean to be anti-authoritarian?

BL: The key phrase is illegitimate authority. There’s a big difference between anti-authoritarian versus anti-authority. One of the points that Noam Chomsky (an anti-authoritarian anarchist) makes is that if a little kid is running in the street and you want to save him from getting run over by a car, you’re acting as an “authority,” and you can justify that authority there.

But he also points out, and I totally agree—there are a lot of books about it—that a lot of authorities out there are illegitimate authorities, and are there to impose a certain power structure. An illegitimate authority is dishonest, is exploitative, doesn’t really care about people—certainly different from a legitimate authority.

Instead of doing straight definitions, I try to give people a sense of authoritarians. There’s a great Lyndon Johnson quotation showing an authoritarian sensibility (by the way, there are a lot of authoritarian Democratic presidents in addition to Republican ones): talking about what he wants in appointees, he says, “I want them to kiss my ass in Macy’s window at high noon and tell me it smells like roses.” And the point is, it was not only Johnson—who demanded unquestioning obedience as an authority in power—but also those asskissers who are authoritarians. Anybody who’s willing to kiss up to any and all authorities just to get ahead—they are also authoritarians.

CM: Is the legitimacy of authority in the eye of the beholder? For every Democrat in the #Resistance movement who feels Trump is illegitimate for, say, not winning the popular vote or some other reason, there is a Republican who will tell you Obama was not legitimate. So how subjective is legitimacy?

BL: Very subjective. It’s based on your judgment of whether somebody is honest and based on your judgment of whether somebody is exploitative.

A good comparison to Trump is really Elijah Mohamed, from the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X is one of the guys I profile in the book as a legitimate anti-authoritarian, and although early on in the game he saw Elijah Mohamed confronting the illegitimate authority of racism, white power, and white control and viewed him as a legitimate authority, he realized later on that Elijah Mohamed was breaking all the laws of his religion, having sex with secretaries, producing babies (and ultimately that he and the NOI were trying to kill Malcolm X), and he realized this guy was an illegitimate authority. And he left the Nation of Islam, opting for certain death (he knew he was going to get killed).

One of the ways Trump got to power was by going after the illegitimate authority of the Republican Party. Just like Elijah Mohamed, he went after guys like Jeb Bush and all these others—Trump’s people knew these guys were illegitimate authorities. But Donald Trump did that to get power for himself, to be able to be exploitative, not to become a legitimate authority himself. There are some Trump believers—though not many—who have come to realize that.

CM: How pernicious is authoritarianism? That is, does one accept certain tenets of authoritarianism and then slowly, imperceptibly become authoritarian, even without noticing?

BL: There were definitely periods in American history where there was greater anti-authoritarianism and periods where there was greater authoritarianism. The 1770s in America were a pretty anti-authoritarian era, just as the 1960s were, and then there are more authoritarian eras, like when Ronald Reagan won office in 1980—he basically got in on his reputation as a strongman who put down student revolts. He was a little more of a charming strongman than the obnoxious guy we’ve got in power right now, but it’s been a pretty long authoritarian era in American society. If you have a population that’s scared enough, they can’t deal with the tension that democracy really requires.

I’m a psychologist, so I work with families too—I have interest in all levels of society, from the US government to the family. We see in certain families that kids who dissent are dealt with in an authoritarian manner, and then there are families that are less authoritarian, where dissent is taken seriously. That’s really the key ingredient. If you have a family or society where dissent is squashed, it’s an authoritarian family or society. Dissent creates tension, and to the degree people cannot handle any dissent, they’re going to squash it, and then you have a more authoritarian family, or a more authoritarian society.

CM: To what degree are we seeing a rise in authoritarianism, a rise in the far right, a rise in neo-Nazism here in the United States because the United States, through the American Psychiatric Association, has pathologized anti-authoritarianism, has made it a mental disease?

BL: I want to make it clear to your audience that the psychiatric assault on anti-authoritarians is only one spoke in the wheel here. There is a criminalization of anti-authoritarians. There are many levels on which anti-authoritarians get marginalized—financially as well. All kinds of things happen to them.

But there’s something that’s increasingly concerning to me in my own profession: the psychiatric assault on anti-authoritarians. There are, increasingly, kids who are oppositional who are being labeled with mental illness. In 1980—coincidentally, the same year Reagan is elected president—the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual, the DSM (back then it was the DSM-3, now it’s the DSM-5), came out with something called “oppositional defiance disorder.” Literally. And one of the symptoms is “refusing to comply with adult rules and requests.”

I’ve got to make this clear: this is not kids who are breaking any laws, even. These are not juvenile delinquents. These are kids who are not doing anything wrong. They are just noncompliant. They are oppositionally defiant. This becomes a mental illness.

Among ex-psychiatric patients I know who are now activists, it’s amazing how many of them who were once labeled with schizophrenia or bipolar (or all these other diagnoses) are essentially like anarchists in terms of their feelings about not wanting to deal with hierarchy or coercion.

I was in grad school when that came out, and I was totally embarrassed by my profession; this was a joke. But people started taking it more and more seriously, and it went from being what a lot of people maybe labeled as another silly psychiatric diagnosis to being one more “disruptive behavioral disorder,” and kids are literally getting drugs for this.

Most kids who are being put on anti-psychotic drugs—heavily tranquilizing drugs like Seroquel, Risperdal, things that have replaced the old-time Haldol and Thorazine stuff—are labeled not with psychoses, not with things like schizophrenia, bipolar, that kind of thing, but labeled with these disruptive behavioral disorders like oppositional defiance disorder. These kids are not necessarily genuine anti-authoritarians when they’re eight, nine, twelve years old—they might not be assessing whether an authority is legitimate or not—but they are noncompliant kids, stubborn kids.

In my book I profile twenty famous anti-authoritarians; a lot of them, when they were young kids, would have been labeled with oppositional defiance. And they mature from just taking pride in noncompliance into taking pride in assessing who is a legitimate and who is an illegitimate authority—and they have the guts and the courage to be able to challenge and resist. We’re taking that population of future anti-authoritarians, vital for democracy, and we’re taking them early on—before they have any political consciousness—and we’re drugging them.

CM: You had an article back in 2012 headlined, “Why Anti-Authoritarians are Diagnosed as Mentally Ill” (titled on some websites as “Would we have drugged up Einstein?”). To this day you continue to receive emails from people telling you they believe their anti-authoritarianism or their child’s has resulted in mental illness diagnoses.

What does that reveal to you about what it means today to be considered mentally ill here in the United States through the American Psychiatric Association? Is mental illness an illness or just a simple lack of conformity?

BL: In certain areas it’s obvious. With “oppositional defiance” it’s very obvious to most people I talk to; in mainstream America they start laughing, the point is obvious. In some other areas it’s not so obvious. But I’ve got to tell you: I’ve been involved in a major political movement since 1994, among mental health professionals, psychiatric survivors, people who are concerned about coercive treatment and the lack of informed choice, and when I compare the regular amount of anti-authoritarians I usually run into, it’s not that many, but among ex-psychiatric patients who are now activists, it’s amazing how many of them who were once labeled with schizophrenia or bipolar (or all these other diagnoses) are essentially like anarchists in terms of their feelings about not wanting to deal with hierarchy or coercion.

In the book I talk about Thoreau and his buddies at Concord in the 1840s and 1850s, and I take a look at the anarchists of the 1890s and the early 1900s. And so many of those people, when I study them, remind me a lot of people I know very well who are ex-patient psychiatric survivors.

CM: You write, “In the 1950s and 60s, the horrors inflicted by Nazi Germany were still on the minds of many Americans. The 1950 book The Authoritarian Personality, which psychopathologized authoritarian personalities, became popular. But by the 1980s, US society had changed. In 1980, Americans elect former actor Ronald Reagan to the presidency; he had previously acquired an authoritarian strongman reputation by putting down student revolts as governor of California. In the mid-1980s, Democrats, wanting to appear as tough as the Republicans, strongly supported anti-crime legislation that has contributed to the United States having the highest incarceration rate in the world, caused in large part by hypocritical drug laws.”

What changed in the United States from the postwar years, after a war against authoritarianism, to the “Greatest Generation,” who fought against authoritarianism, suddenly supporting Reagan (only twenty-five years later!)? Is this an authoritarian backlash fueled by fear of the the chaos that authoritarians saw happening in anti-authoritarian culture in the sixties? Is Reagan and the rise of authoritarianism all those damn hippies’ fault?

BL: There are a whole bunch of elements to that. One has to do with violence. I don’t romanticize all anti-authoritarians; there are some who move into violence, and usually (in the United States, anyway) that helps the cause of authoritarianism.

An example of that was the rise of the Weathermen. I understand how that happened. I’m a psychologist. I understand that these guys felt totally enraged, and felt that none of the protests would stop the Vietnam war. They felt a combination of rage and impotence. In the late sixties and early seventies they moved towards thinking that Students for a Democratic Society wasn’t working and they have to do something stronger, and they moved into violence. They moved into bombings. And shortly after that, Nixon wins the 1972 election in a landslide against McGovern.

Part of why he wins is exactly what you just said. I understand how frustrated anti-authoritarians can move into violence, but history shows it pretty much doesn’t work. There are some weird exceptions, but they are the exceptions that prove the rule. Whereas state violence against anti-authoritarians generally works out pretty well. Like Kent State. But anti-authoritarians moving into violence, although I totally understand it psychologically, feeds into the hands of authoritarians because it gets the population to believe we need to have strong leaders, because we’re afraid of this kind of thing.

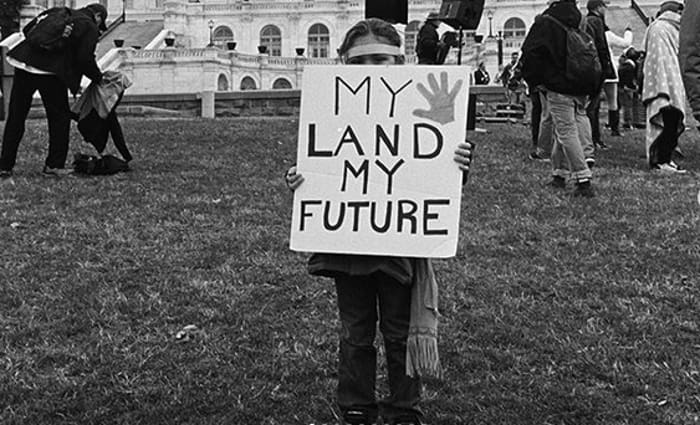

Psychiatry is becoming this totalitarian force. It meets the needs of keeping the status quo. Why are Native American kids killing themselves at hugely high rates? If you can call it a mental illness, then you don’t have to take a look at centuries of massive oppression that has happened to them that have created this thing.

CM: How much does the dismissal and disregard of anti-authoritarians either by the government, or by social peers, or by the media, provoke anti-authoritarians into violence? Are they ignored to the point where they figure that the system is not working for them, so they have to work outside of the system to get it changed?

BL: That’s always what happens. We can go back and read the speeches of Malcolm X, and that’s what he said over and over. He predicted the violence. He said, “Look, no one is listening to guys like me, so you’re going to see riots.” And that’s ultimately what happens. He pushed and prodded. They would say, “Are you trying to make it happen?” And he said, “I don’t have to. Take a look at history. That’s what happens.”

When people who are dissenting are not taken seriously, ultimately there are going to be certain elements among those folks who feel so frustrated, so enraged—a sense of pain over personal and political injustice, coupled with a sense of impotency, is kind of a psychological drug. A lot of people just move into heavy depression over that, get suicidal. That’s probably the majority. But a certain element of people will move into violence, thinking “I’ve got to do something.”

I want to make the case clearly here that we certainly have to understand the psychological process, but it doesn’t help. The folks who have been triumphant as anti-authoritarians, who do accomplish things, are not the folks who moved into that violence. They were effective not just through dissent, either, though; they were effective through a willingness not to cooperate, a willingness to disobey—which is very different than violence.

CM: How much has anti-authoritarianism here in the United States, been killed off by authoritarians in the United States?

BL: That’s what they’re going to do. If I’m an authoritarian, I want to make sure I get rid of as many anti-authoritarians as I can. And you don’t have to kill them. The first thing authoritarians are going to do is just ignore. That’s the first rule. Try to ignore them, poo-poo them. If that doesn’t work, then we’ll get our professionals, we’ll criminalize them—that’s been done in American history—we’ll psychopathologize them, we’ll marginalize them financially. There’s a whole bunch of things.

If you’re an authoritarian, you know there doesn’t have to be a majority of this group (this oppressed group that I care about, anti-authoritarians), just a significant minority of them who are voicing the will of the majority, to create some change. So you want to make sure, if you’re an authoritarian, that these folks are not around at all.

CM: All of this pathologizing, this making of anti-authoritarian dissent into a mental disease—can we blame this on the pharmaceutical companies for pushing drugs on psychiatrists and unduly profiting?

BL: That’s certainly one of the major reasons, just like prisons for profit are one of the major reasons we have these ridiculous incarceration rates in America. Pharmaceutical companies are profiting off of drugging all of us, including oppositionally defiant kids—that is one of the pillars.

But I think there are other reasons as well. Psychiatry is becoming this totalitarian force. It meets the needs of keeping the status quo. Why are Native American kids killing themselves at hugely high rates? If you can call it a mental illness, then you don’t have to take a look at centuries of massive oppression that has happened to them that have created this thing. There are massive amounts of substance abuse and suicide going on.

But the pharmaceutical companies are a big reason here. They have annexed psychiatry. They totally control everything that goes on in there. But there are other reasons, too.

CM: You write about your embarrassment with the mental health profession and how it increased throughout your schooling and internships, and you struggled over whether you should quit or continue on to get your PhD, which, you argue, lacks legitimate authority. Yet it has provided you with what you describe as the credibility for the mainstream media, which for the most part bases its assessment of authority solely on credentials.

If that’s the case, then how authoritarian is our media? How illegitimate is the authority of those whose voices fill the media?

To the extent that you believe that the United States is something that it’s not, you are complicit in authoritarianism, as opposed to dealing with the truth of it. It’s just like being in a problematic, dysfunctional, abusive family.

BL: If you’re a journalist, you should be an anti-authoritarian. If you’re not an anti-authoritarian, you’re going to be a lousy journalist. A real journalist is somebody who is going to question the legitimacy of all their sources, including the American Psychiatric Association, including the FDA. A real journalist questions, and they’re going to assess if maybe someone is corrupt, if they’re not telling the truth.

There are fewer and fewer journalists like that. They still exist, but they are having a more and more difficult time making a living. I know a lot of these folks myself. Once upon a time, if you were anti-authoritarian, one of the great professions to go into was journalism. That was your job, to assess whether these authorities knew what they were talking about or if they were liars, and you could make a living doing that. That’s getting more and more difficult.

CM: You write, “Dissent without disobedience is essentially no threat to people in power. Clever authoritarians welcome dissent without disobedience, since it can be easily ignored, and provides the illusion of a free and democratic society. Only disobedience can threaten authoritarians.”

How much do we, here in the United States, have the illusion of a free and democratic society? And is the greatest trick that authoritarians ever played on us, making us believe we are a free and democratic society?

BL: Yes, absolutely. But dissent should work if you’re living in a democratic society. And we have plenty of dissent here, in many different ways. Not just rallies. Opinion polls show a massive majority of people, seventy percent of Americans, favor Medicare for All. That’s a dissenting opinion. There are opinion polls showing that the majority of Americans want free college tuition at public universities. Why don’t we have these things? If dissent were effective, we’d be living in a democratic society.

Part of the way you know you’re living in an authoritarian society is when dissent means nothing. When two million people show up opposing a war and it means nothing, you’re living in an authoritarian society. But it’s not a black or white thing. There are shades of authoritarianism and kinds of authoritarian societies. I’m not saying that the United States is the most authoritarian society out there. It’s certainly not. But when mere dissent is ineffective, that’s when you need anti-authoritarians, who are much more comfortable moving past dissent.

An example for me is the difference between a guy like Bernie Sanders versus his hero, Eugene Debs. Bernie Sanders is very comfortable with dissent. He made a name for himself, became one of the most popular politicians in America. But was he willing to disobey the Democratic Party? No. This is unlike his hero Eugene Debs, who disobeyed the Democratic Party. He had supported Cleveland several times for president, but Cleveland threw him in jail for leading a strike against the Pullman company, who had cut wages. And then Wilson, another Democrat, threw him in prison for ten years for giving a speech against the war. It became clear to him that dissent wasn’t working, and he had to disobey.

Debs became an anti-authoritarian later in life. He was a much more polite dissenter early on, but he moved into being comfortable with realizing that if you’re living in an authoritarian society you have to disobey. You have to strike. Early on as a labor leader, he believed that you could have polite discussion and collaboration and it would all work out. Then it became clear to him that the guys running these companies didn’t care about the workers, they wanted to make as much money as possible, and the only way to get any kind of equity was to strike.

We have to understand that with authoritarians in power, that’s the only thing that’s going to move them. Boycotts, strikes, those kinds of things. They’re not going to care about dissent. In fact, for them, in America today, if you have dissent, it just serves the illusion that there is democracy, so they actually like that. They’re not threatened by that at all.

CM: To what extent does believing that the United States is a free and democratic society amount to complicity in, if not capitulation to, authoritarianism?

BL: To the extent that you’re in denial of the reality of what US society has been all about historically—what it’s done to Native Americans, what it’s done in Vietnam, what it’s done in many areas to many oppressed groups. To the extent that you believe that the United States is something that it’s not, you are complicit in authoritarianism, as opposed to dealing with the truth of it. It’s just like being in a problematic, dysfunctional, abusive family. If you’re getting beat up by your spouse on a regular basis and you still want to believe your spouse loves you, you’re ultimately going to become complicit in an authoritarian situation. Dealing with the truth of things is very painful. It creates a lot of tension. But it is required to be an anti-authoritarian.

CM: Bruce, fantastic having you back on the show again. Thank you so much.

BL: Thank you.