Transcribed from the 16 March 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

There is a growing tendency towards increasingly anti-democratic ways of governing in many of the advanced democratic countries. Obviously if there were some kind of balance between democratic concerns and capitalist concerns, it’s the capitalist concerns that have been winning out.

Chuck Mertz: Sovereign debt is being repaid at a rate it has never been repaid in the past. Here to tell us why, scholar, essayist, commentator, and political economist Jerome Roos is author of Why Not Default? The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt. We are speaking to him live from Amsterdam. Jerome is an LSE fellow in international political economy at the London School of Economics, and the founder of ROAR Magazine.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Jerome.

JR: Hey, Chuck. Thanks so much for inviting me on the show.

CM: Sovereign debt is the amount of money owed by a government through borrowing, but sovereignty is the supreme power or authority given a self-governing state, or that power over another state. Jerome, that made me think: is sovereign debt simply a nation’s debt, or is sovereign debt the debt that has authority, sovereignty, power over a nation? Is debt the sovereign entity, not the state? How much power can debt have over a nation and its government?

JR: That’s a great question, and one that is super salient in Europe—and also the United States, in relation to Puerto Rico for instance. Over the past thirty or forty years, the power of debt to shape the fortunes of countries has increased considerably. There’s been a real shift in the global political economy that has seen the power of creditors, the people who hold that debt, increase by a vast amount.

CM: Is debt authoritarian, like a dictatorship that imposes undemocratic demands on a nation and its citizens?

JR: We’ve seen in the past that it can come to dictate the ability of people to influence their own government, to shape their own lives. If we take the example of Greece, there’s been a thorough undermining of democratic responsiveness on the part of the Greek government as a result of its need to repay debt to the European creditors that lent out the money in the lead-up to the crisis. The national sovereignty of the Greek state has been hollowed out to a very important extent as a result of the way that crisis has been managed.

The European creditor states, led by Germany and France, and European institutions including the European Central Bank and the European Commission, have (together with the International Monetary Fund, which is based in Washington, DC) come into the Greek political scene in an attempt to get the government to repay its debt to European banks, and not delay those payments in any way. They’ve demanded a number of austerity measures, far-reaching privatizations, and all kinds of cuts in salaries and pensions in order to free up resources for the Greek state to continue paying its debt.

This has thoroughly undermined the responsiveness of the Greek government to its own people. You’re asking whether debt can be authoritarian—I think it is definitely anti-democratic. It is about creditors coming to impose certain solutions to the crisis on debtor countries, and that thoroughly undermines the democratic capacity of the governments in place.

CM: What happens when governments don’t react to voters but they react to banks? What happens when they react to debt and not democracy, finance and not democracy? How does a government change when they’re not thinking about what their voters want but what their lenders want?

JR: Over the last thirty or forty years, governments have tended to become increasingly technocratic in the way they manage economic affairs. That includes not just debt repayment, but a host of other things as well, like shaping a “good business environment” that will attract investments from abroad. But debt repayment is a crucial lever in the process of empowering technocrats at finance ministries and at the central bank, giving them more authority to act with what is considered to be the behavior of a responsible debtor.

In the process, we see that the lack of democratic responsiveness—the growing power of technocrats within the government and the sidelining or marginalization of those who seek to respond to more popular demands—ultimately leads to a huge loss of faith, among the populations in debtor countries, in their own governments and in the capacity of political institutions more generally to respond to people’s concerns.

Again, taking the example of Greece, what happens in a situation like this is mass protests. We saw that already with the start of the crisis in 2010, and that continued right up until 2012 with the second bailout by the European government. Eventually, in 2015, the two leading incumbent center-left and center-right parties were ousted from office by a new anti-establishment coalition that was known as Syriza, or the coalition of the radical left—who, at the time at least, were saying that they were going to overthrow this technocratic way of government and they would restore democracy and end the austerity regime of the European creditor states.

Obviously that’s not how things turned out. But the tendency towards anti-establishment politics is an element that we see occurring in these debt crises. Another famous example of that is Argentina in 2001. There was a huge crisis there for many years that led to the emergence of massive social movements, with very innovative grassroots practices—solidarity economies as well as all kinds of direct democratic forms: neighborhood assemblies, forms of worker control over enterprises through the reclaiming of factories. All of these movements were really a response to a lack of democratic responsiveness on the part of the government, and the fact that the government had been completely bought, essentially, by foreign investors and foreign creditors.

In the Argentine case it led to a very different outcome from what we saw in Greece. Those movements were so powerful that they managed to oust the sitting president and force the country into default, which to this day remains the largest sovereign default in world history.

Was this our choice? I don’t think it was our choice. It was a response on the part of ruling elites to the crisis of the 1970s, a way for them to buy time in the event of a very deep crisis of profitability. That ended up introducing a whole host of new problems that led to all the crises that we’re seeing today.

CM: Has finance won over democracy?

JR: It has certainly won out so far over the past thirty or forty years, in the sense that there is a growing tendency towards increasingly anti-democratic ways of governing in many of the advanced democratic countries. Obviously if there were some kind of balance between democratic concerns and capitalist concerns, it’s the capitalist concerns that have been winning out.

That’s not necessarily a surprise, but it’s nevertheless an important development that we must try to explain, in order to understand how we can begin to roll back some of this capitalist financial power. Because yes, what we see in Puerto Rico today, what we see in Greece, what we’ve seen in Latin America over the last twenty or thirty years, is a fundamental undermining of democratic processes in the name of the need to repay foreign debt.

It’s a longer dynamic, by the way. It goes back in history. We can go back all the way to the age of imperialism, and see how the United States sent marines to several Caribbean and Central American countries in order to force them to repay their debts during the crises of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We can look at how European creditor states literally invaded Egypt in order to force it to repay, and imposed all kinds of international financial conditions on Greece, going back to the 1820s.

This is a long-running development. But in the last thirty or forty years, that development has radicalized, and the means through which democracy is undermined by finance are less and less dependent on the military—less and less dependent on sending gunboats abroad—and more and more achieved through the operations of international finance, of financial markets, of credit provision, and of course the intervention of major international financial organizations like the IMF and the World Bank.

CM: Did we choose finance, over democracy, to be our ruling power? Did we choose that?

JR: I don’t think any of us chose that. That was something that happened in the 1970s in response to the crisis of capitalism at the time. If we can go back in history a little bit, basically after the Second World War an international economic order emerged under the leadership of the United States and Great Britain that tried to reconcile, at least to some extent, democratic responsiveness with the need for economic integration at the international level. Obviously that was not a very democratic model, because it was dependent on the exclusion of many marginalized people. It was dependent on hierarchies of race and gender. It was dependent on all kinds of imperial relations.

But the idea was that the advanced capitalist countries could only prevent a major economic crisis like the Great Depression of the 1930s by imposing some limits on the ability of capital to flow across borders. The regime that emerged after the 1940s was called the Bretton Woods system. The idea was that capital would be confined within nation-states to make sure that it would not unleash the kind of chaotic situation that we saw during the 1920s and 1930s. That model was relatively successful for twenty or thirty years, but it began to break down in the 1970s.

What we have to try to understand if we want to explain the rise of finance in the contemporary period is how policymakers responded to that crisis in the 1970s. They realized that there had been a huge crisis of profitability—profit rates were not as high as they had been in the immediate postwar decades; there were all kinds of social movements emerging; all kinds of international conflicts were emerging. In that context, it seemed like a good idea, especially to US policymakers, to try to “unleash credit,” to try to unleash finance in order to get capitalism to grow again, in order to make sure that the United States could tap into that credit in order to beat its major international opponent, the Soviet Union, in the competitive struggles that were playing out in the international realm.

At the same time, that credit provision—it was hoped—would boost the capacity of American firms, and especially American banks, to pull the country out of the stagflation period of the 1970s. That was to some extent successful in at least temporarily reinflating the fortunes of US-based and UK-based capital. But obviously it also introduced a whole host of contradictions into the system that made the global economy much more subservient, on the one hand, to financial interests, and on the other hand also much more vulnerable to financial crises.

That’s really when we start seeing a huge increase in the number of international debt crises, something we hadn’t seen in the 1940s, the 1950s, the 1960s, or even the 1970s. Starting in 1982, a number of developing countries start getting into serious debt troubles. Mexico is the first one of them. I try to explain how these crises since then have been managed, and how that reflects the growing power of finance in all of this.

So going back to your question, was this our choice? I don’t think it was our choice. It was a response on the part of ruling elites to the crisis of the 1970s, a way for them to buy time in the event of a very deep crisis of profitability. That introduced a whole host of new problems that led to all the crises that we’re seeing today.

CM: What people might be thinking is, “Of course you pay back your debts. That’s just what you do. Of course a nation would pay back their debts. They don’t want to go bankrupt, they don’t want to be outside of the global market. That’s just what you do.”

Is paying back debt any more prioritized today than it was in the past?

JR: It definitely is, and that goes to the crux of the problem. You’re absolutely right to say there is a widespread expectation that countries, individuals, households, firms—that everyone, essentially, should pay their debts, because that’s the thing to do. There’s a very interesting book written about that by the anarchist theorist David Graeber, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics, in which he very brilliantly shows some of the moral dilemmas at work in that assumption.

That comes out very clearly in the German word or the Dutch word for debt, which is Schuld. That word means, “debt,” but it also means “guilt.” In a way, the debtor is always already presumed to be guilty for their predicament. It is their fault that they are in debt; therefore the assumption is that they should pay in the event of a crisis, and they should be the ones to suffer if they can’t repay the debt. This is a very deeply ingrained type of morality that has been with us for hundreds of years, or even millennia.

But interestingly, when it comes to sovereign debt we find that the situation is very different. Prior to World War Two it was very common for countries, when they entered into a major crisis, to simply stop repaying their debt. If we take the example of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the vast majority of debtor countries in that crisis simply stopped paying their debts. They imposed what were called “unilateral debt moratoriums.” The vast majority of Latin American countries and the vast majority of European countries simply stopped paying American bondholders, because they were in trouble and couldn’t repay their debts.

We’re in a situation where if credit circulation stops, a lot of people will have a lot of difficulty getting to their basic needs. You won’t be able to draw on your credit card anymore to buy basic goods. This growing dependence on credit really renders governments increasingly subservient to financial markets.

With the resurrection of global finance in the wake of the crisis of the 1970s that I just mentioned, there’s been a huge shift, in terms of prioritization, in the management of these crises. Since the 1980s, these unilateral debt moratoriums that were so common prior to World War Two have been all but ruled out. They have hardly ever happened since. Especially in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, there’s been a very stunning absence of such sovereign debt defaults. In fact, as you mentioned in your introduction, the amount of sovereign debt that is in default today is lower than it has been at any other stage in history in the wake of a major international crisis.

That’s a puzzle that we must try to answer, and the power of finance is really the key to that puzzle.

CM: You mention the wave of sovereign defaults that caused international capital markets to collapse during the Great Depression, and you mention the fallout from nonpayment and other defaults that took place throughout history. Are sovereign debts paid back because the debtor nations fear something worse could happen—including a global economic crisis that could be even more debilitating to the borrower than the debt is?

JR: There is absolutely something that they are afraid of, but I don’t think it’s necessarily an international crisis. It’s a collapse of their domestic economies. Since the 1970s, all countries around the globe—both developed and developing countries—have become much more dependent on credit. That’s not just for their governments. It’s not just that governments become more dependent on credit, which they have, but also that domestic firms and domestic households are ever more integrated into the financial market.

We’re basically in a situation where if credit circulation stops, a lot of people will have a lot of difficulty getting to their basic needs. You won’t be able to draw on your credit card anymore to buy basic goods. A firm won’t be able to get credit or investment anymore to continue its activities. And a government won’t be able to get the credit that it needs to make whatever it is that it spends money on: welfare expenditures, military expenditures, infrastructure investments, you name it. This growing dependence on credit really renders governments increasingly subservient to financial markets, and it leads to a situation where there is a huge concern that if that dependence is upset somehow—if you scare away your creditors and they stop lending to you—you’ll find yourself in a much deeper crisis. You may find yourself in a situation where your domestic economy virtually collapses.

That’s kind of what we saw in the Argentine case that I mentioned before. When Argentina defaulted in 2001, for about three to six months, all credit circulation in the economy ground to a halt. The financial system collapsed; many, many people lost their jobs; and a country that had been one of the richest in the world found itself in a situation where about half the population was now in poverty and a significant share of the population could no longer even afford food.

It is in that context that social movements emerged and innovative practices of barter trade and solidarity economies arose. But governments tend to be very afraid of that type of situation, because they cannot control the social and economic fallout of such a profound collapse in domestic credit circulation. That’s one of the main reasons that countries insist on paying their debts, even when they cannot.

CM: You write, “If we were to draw the assumptions of neoclassical economics to their logical conclusion, a self-interested government should try to pile up as many foreign obligations as possible before repudiating them in total. As rational lenders would in turn refuse to extend further credit to opportunistic borrowers, the result would be a collapse of global capital markets, meaning there should be no such thing as external debt to begin with. Yet this is clearly not what happens.”

What does it reveal to you about the nature of sovereign debt when it does not follow the logic of today’s neoclassical economics? Or for that matter, what does it reveal about neoclassical economics?

JR: To tackle the second part of your question first: it reveals a lot. It reveals that neoclassical economics cannot account for one of the most fundamental dynamics in the world economy today: namely, the huge increase in sovereign debt on the one hand, and on the other hand the growing insistence of countries to actually pay those mounting debts even in times of financial crisis. The fact that neoclassical economics can’t explain that ultimately comes down to neoclassical economists making a number of assumptions that leave some of the most important dynamics in the management of these crises out of sight.

I’ll mention two of them: one is what I call the redistributive effects of sovereign debt. Neoclassical economists treat a country as if it is somehow a single entity, and the government represents that single entity, and the government decides whether or not to repay the debt based on a rational calculation of what the costs and benefits are of payment or nonpayment. On the basis of that rational calculation, it will decide whether or not it repays its debt.

Obviously countries are not unified actors. Countries are riven with internal divisions. There are people inside a country who stand to benefit from repayment, and there are people inside a country who stand to lose from repayment. The reason for that is pretty obvious: some people in a country are likely to be exposed to their government’s debt—these tend to be big banks, the big financial investors who may have bought some of their own government bonds and who depend on the financial stability that comes with debt repayment. On the other hand, there are working people, there are ordinary middle class people, there are people who depend on all kinds of public benefits, students, you name it, who are much more at risk from the austerity measures that come with full debt repayment. These people are much more likely to lose out when the debt is repaid in full. Over time they may come to favor non-repayment as a beneficial outcome of the crisis.

In these crises there are all kinds of struggles and conflicts that emerge, and neoclassical economics is completely incapable of addressing those, because it doesn’t consider the politics of sovereign debt repayment, it only looks at the economics. That is one of the major reasons why neoclassical economics can’t really explain much about these crises, because it depoliticizes them, and it ignores the class conflict at the heart of them.

Another thing that comes with that, obviously, is that it ignores the power relations that I mentioned before. It is so used to explaining the world in terms of rational cost-benefit analysis, it doesn’t really take into account the power differentials that exist between different groups or even between debtor countries and their international creditors. It is when we start looking at these power dynamics that we can start to explain why it is that countries repay, even when their debts are growing to a level where they find it more and more difficult to do so.

Depoliticization makes us think of the capitalist system as a way that different actors try to maximize their benefits, and can, in the process of doing so, achieve better outcomes for all. This is actually not the case, because there are fundamental power dynamics at the heart of the system—some actors are capable of forcing others to do something that they don’t want to do to begin with, and that may not even be good for the creditors themselves in the long run.

CM: That seems like a huge oversight. Why depoliticize economics? Obviously everything is political. What’s the intent? Why would you try to depoliticize economics?

JR: We can give two answers to that. One is the innocent one, the other is the political one. The innocent one is that power tends to be a variable, if you want to speak in purely scientific language, that is very difficult to operationalize—that is, it is very difficult to show it at work in a particular case, especially if you are using quantitative methods like economists do. If you try to understand the world as basically an aggregation of a series of numbers, and you try to run complex regressions on that in order to understand important economic outcomes, you’re not going to include power in that because power is very difficult to demonstrate in any quantitative fashion.

To understand the way power works, you need a qualitative and historical approach. That type of methodology has all but disappeared from the discipline of economics, which has become increasingly dependent on formal modeling and all kinds of mathematical calculations in order to explain the way the economy works. So that is the innocent explanation: simply that their methods are not adequate for grasping power dynamics.

But there is a deeper process at work there, and that it is ultimately ideological. Depoliticizing sovereign debt, and depoliticizing the way these crises are managed ultimately serves a certain function, which is to shift attention away from the power dynamics that are at work, and to account for the way the economy works as essentially a set of bargains between different actors that are all constantly trying to maximize their utility, trying to maximize their benefits, and there may be some kind of conflict going on there, but it’s always within the market, and there’s never any power involved.

That depoliticizes, at a broader level, the whole capitalist system, and makes us think of the capitalist system as a way that different actors try to maximize their benefits, and can, in the process of doing so, achieve better outcomes for all. This is actually not the case, because there are fundamental power dynamics at the heart of the system—some actors are capable of forcing others to do something that they don’t want to do to begin with, and that may not even be good for the creditors themselves in the long run.

There are a lot of problems there, but one of them is certainly that there’s an ideological operation in neoclassical economics that needs to be exposed and dismantled.

CM: You write, “By noticeably intensifying distributional conflict over scarce public resources, sovereign debt crises tend to lay bare underlying power dynamics that during normal times are quietly at work beneath the surface.”

What dynamics are commonly revealed, and why does debt reveal these otherwise hidden power dynamics?

JR: I mentioned this huge growth in the power of finance over the last thirty or forty years—but that was not immediately obvious to many people prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, because finance was providing a lot of cheap credit to people, and people were benefiting a lot from that situation. If credit is abundant and you’re able to borrow a lot of money to engage in all kinds of consumerist activity, you’re not going to complain about that situation—until, at some point, the tap is closed and credit suddenly becomes much more expensive, and it becomes much more difficult to repay those debts.

Then, suddenly, what is revealed is a situation in which the crisis is managed to the advantage of some people and to the disadvantage of others. If we look at the debt crisis at the heart of the US mortgage crisis that precipitated the financial crash of 2008, we find that the people who ended up paying for the crisis were mostly marginalized households, especially African-American households, and especially African-American households headed by single women. They ended up losing out enormously because of the predatory lending that had happened prior to the start of the crisis.

That predatory lending was not very visible when the going was good. But there’s a saying in investor circles on Wall Street that “you only see who’s naked when the tide goes out.”

That’s really what happens in these debt crises. It becomes possible to see power dynamics that during the good times are largely obscured. Again, the Greek case is a very good example of that. Everyone thought that Greece was a wonderful investment destination prior to the crisis. And everyone thought that the European Union was a wonderful thing for Greece, because it was leading to a new era of development for the Greek economy. But what happened in the wake of the financial crisis was very different, of course. Greece became hugely disadvantaged as a result of its subordinate integration into the Eurozone, and the consequences that it suffered only became visible in the course of that crisis. It showed that there are fundamental inequalities at work within the European Union, and within the global financial system, that leave some countries and some people at a considerable disadvantage.

CM: You mention that even Greece’s nominally leftwing government has insisted on repaying an essentially unpayable debt. How is Greece’s debt unpayable?

JR: It’s unpayable in the sense that the government has been forced to cut into all kinds of social provisions to be able to continue repaying its debt; in other words, the government has decided to favor its legal contracts to its foreign investors over the social contract to its own people. The social contract at home had to be broken in order to make it possible to pay the debts abroad. That process, to me, is a sign of the fact that this debt is essentially unpayable.

They can continue to repay, because they will find new money here or there. But the cost of that is so immense for the domestic population that we’ve seen literally one of the worst humanitarian calamities in a developed European country outside of wartime. We’re not aware of any relative deprivation on such a large scale outside of major conflicts like the Balkan wars or the transition to capitalism in the former Communist states of eastern Europe. What happened in Greece is really off the charts, in terms of the numbers of people who were thrown into poverty, the numbers of people who lost their jobs, the dismantling of social services. To give one example, the healthcare budget was slashed in half. Many medicines are now inaccessible. People can’t get basic healthcare services.

This, to me, shows that the debt was unsustainable. I am not alone in that assessment. Many people at the International Monetary Fund, for instance, were already saying it at the beginning of the crisis. Many very serious economists, by no means leftwing ones, have been arguing from the very start of the crisis for the need to cancel some of the debt and to reduce the total amount that Greece owes to its foreign creditors, to make it possible to pay the rest on less onerous terms.

CM: You write, “Across the globe, parties of the left have begun to adopt the mantra of budgetary discipline and debt repayment that had long been the prerogative of the fiscally orthodox right. In the process, domestic party politics has effectively ceased to explain prevailing policy outcomes, rendering national elections increasingly meaningless.”

Has global finance made democracy obsolete?

JR: It has not made democracy obsolete, but it has fundamentally undermined the established patterns of democratic representation that we have today. One of the challenges that we will see emerging over the next years and next decades is the struggle that will emerge from below in order to try to reclaim democracy for ordinary people and roll back financial power, and business power more generally, by on the one hand reclaiming some of the existing institutions, but on the other hand innovating new democratic forms and new forms of social organization from below.

I’m very hopeful that some of that may happen in the years to come. We already see it emerging in a variety of interesting developments, whether it’s the rise of new democratic socialist leaders in the UK and the US, or whether it’s the emergence of a very powerful municipalist movement in cities like Barcelona—but also in the US. There’s a new initiative called Symbiosis which is trying to draw together people from different strands of the libertarian socialist movement.

All of this shows that there is growing concern among people that democracy has been undermined, and a growing need not only to reclaim the existing democratic institutions, but also to develop new ones that are truly radically democratic, that are truly responsive to people’s concerns, and that allow for a significant degree of popular participation. That is something that we need to pay attention to, and it’s something we need to direct our energy towards.

CM: Jerome, I really enjoyed our conversation. Thank you very much.

JR: Thank you so much, Chuck, I really appreciate it.

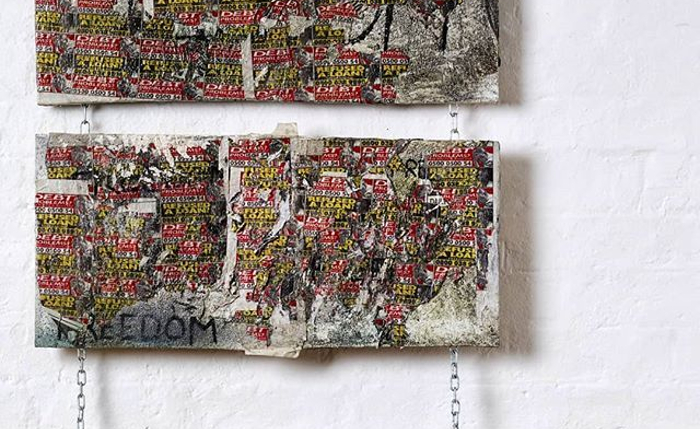

Featured image source: Bryden (Instagram)