Transcribed from the 18 May 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Art reminds us to look at things differently. That encompasses dissent, but it also encompasses awareness—just being aware of being alive and how strange the world is. These things are so profound, and yet they slip away very easily because we take them for granted.

Chuck Mertz: We are constantly busy—always checking our phone, always logged in to whatever social platform we prefer. We are forever occupied in a virtual reality that is nothing more than a marketplace that buys and sells us, turning us into nothing but goods for profit. And there’s nothing we can do about it.

Actually, we can “do nothing” about it, and possibly rebel against the attention economy that insists we always watch. Here to help us learn the revolutionary power of doing absolutely nothing, multi-disciplinary artist and writer Jenny Odell is author of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy.

In one of Jenny’s favorite projects, she created the Bureau of Suspended Objects, a searchable online archive of two hundred objects salvaged from the San Francisco dump, each with photographs and painstaking research into its material, corporate, and manufacturing histories. Jenny has exhibited her work all over the world.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Jenny.

Jenny Odell: Thanks for having me.

CM: What is the attention economy?

JO: The attention economy, on the literal level, is just the buying and selling of your attention. There are obvious design elements to the platforms that we use that are intended to keep you on them for as long as possible, not to mention engaging with as much content as possible. That’s really just design and marketing practice. But I also tie the attention economy to larger ideas: that if you don’t express yourself constantly online, you no longer exist; ideas of the personal brand, of staying “relevant.” There are larger psychological and behavioral things that come out of those specific design elements.

CM: Why is it so successful? Especially in light of knowing how it invades our privacy, and having our right to privacy enshrined within the constitution—what explains to you why social media is so successful, if we’re supposed to be putting so much value in our privacy?

JO: Some of it is just actual addictiveness. There’s been a lot of other writing on that. These things are designed to exploit certain aspects of how we do or think about anything, and they’re very well designed to do that. Some of it is probably not intentional. There are also a lot of books coming out about “how to break up with your phone” or “digital minimalism.” These books wouldn’t be written if it were easy for us to walk away from these things.

On the broader level, there’s a privileging of the obvious and the visible, and this idea that by engaging with these things and representing your life on them that you’re “producing” something. You might not think of it as productive, but you are constantly making utterances or posting things, shouting into this void. Once that becomes entrenched, or once we start to take that for granted, then sitting by and not saying anything, not rendering oneself visible in those spaces, starts to feel very unnatural.

CM: You write, “We submit our free time to numerical evaluation, interact with algorithmic versions of each other, and maintain personal brands. For some, there may be a kind of engineered satisfaction in the streamlining and networking of our entire lived experience. And yet, a certain nervous feeling of being overstimulated and unable to sustain a train of thought lingers.”

Why does this concentration on our “brand” undermine our ability to concentrate?

JO: The philosophy of the personal brand exists in that realm of the very short loop of attention. If you spend a certain amount of time on Twitter, you start to feel crazy. I don’t think I’m alone in thinking that. Not to say that it’s not useful for some things, but it’s a very myopic and claustrophobic view—not only of what’s happening, but of the self.

I believe in an ecological model of the self, where it’s hard to draw a line around the boundary of the self. To accept that makes you open to being surprised, to learning that you’re wrong, to simply learning new things, becoming a different person. That’s the opposite of the personal brand and the optimized, streamlined self, which comes out of this idea that you should “Be Yourself,” that you should have an identifiable and unchanging pattern of preferences. That ultimately just makes it easier to advertise to you. There’s a reason for encouraging something like a personal brand and this pattern of habits and preferences.

CM: So do we live in a state where we are always reacting, replying, and responding, but never concentrating, contemplating, or considering our actions deeply? It’s like a news outlet that prioritizes being the first to report on a story over being the most accurate to report on a story. Is that the kind of situation that we find ourselves in, that first is more important than best?

JO: That’s a really great comparison. It also points to this idea that we have to have a “take” on everything. News outlets at least have a reason, a business reason, to do that. But for individuals, when something happens a lot of people feel like they are somehow obligated to have some immediate hot take on it, rather than sitting with that information for a while—and not just sitting with it, but getting more context, trying to get different sources of information, or waiting a while until that information comes out, and then waiting even longer to decide what you think about it or reflect on it or synthesize it with other things that you know. We all know that things like that take time, and that’s the time that is being taken away from us.

CM: You point out, “Already in 1877, Robert Louis Stevenson called ‘busyness’ a symptom of deficient vitality, and observed ‘dead-alive, hackneyed people about who are scarcely conscious of living except in the exercise of some conventional occupation.’”

You then add, “On the collective level, the stakes are higher. We know that we live in complex times that demand complex thoughts and conversations, and those, in turn, demand the very time and space that is nowhere to be found.”

Are we too busy to address the greatest challenges of our time, like climate change, racism, misogyny, inequality, and whatever else you’d like to add to that list? Are we too busy to make life, now and in the future, better? Is that why we’re not addressing these major problems, because we’ve just made ourselves too busy?

JO: I’m not sure. There are people who are successfully doing that work, so I want to acknowledge that. I also don’t want to put the onus on us for being too busy. One of the ways I’m trying to distinguish my book from self-help is that the typical cadence of a self-help book is “You have a problem, and this book will give you the tools to solve it once and for all, and if you don’t solve that problem, that’s your fault.” My book is different; while I am addressing it to the individual and I am talking about the promise and potential, on an individual level, of learning to redirect one’s attention, I am also situating the problem of the attention economy and of “busyness” as part of a cult of productivity that we’ve all been steeped in. Also (to come back to the economic reality), a lot of people are just trying to make it work. There are a lot of people who are just very busy trying to make ends meet.

On a simple level, attention to place is being aware—looking at it at all, and then starting to wonder what these things are, and wondering about different patterns. What makes this place different from another place? That, to me, is resisting the placelessness of what we experience online, where everything is the same, and lacking in spatial and temporal context.

I don’t know if I would characterize it as us “making ourselves too busy” to do this stuff—maybe there are some cases in which we subscribe to the cult of productivity without needing to, so maybe that falls into that category. But there are people who are doing activism, and then there’s another group of people who would like to be involved in that—or be involved more effectively—but are feeling too distracted and disassembled to be able to.

CM: Why does communicating more lead to communicating worse? If we do it so much, why can’t we do it well? This reminds me of how bad we are at critically consuming media despite the fact that we consume so much media. Why does communicating more lead to communicating worse?

JO: It has to do with style, and depth—or lack of depth. There was a study somebody did where she interviewed activists on how social media had worked and not worked for them. One of the things they observed was that actual political dialogue takes time. It has an incubation time, and it also has, in a way, an incubation space. And they also noted this absurd situation where if everyone is doing something, you have to do it. If everybody is constantly shouting—and shouting short things, short things that are designed to grab your attention—you also have to do that.

There’s another situation which I’m sure people feel rueful about, but “you have to do it”: there are activists and causes that have to take on the language of marketing, because that is what we’ve all learned how to do. We’ve all learned how to grab someone’s attention within this mass of information.

So it’s not even necessarily an issue of what’s being said, it’s how it’s being said. And that format doesn’t allow for that longer dialogue or a more nuanced idea. In the same study, this researcher says this is the reason that print media has stayed important in activist circles, because it’s a slower medium and gives people more time to discuss the ideas.

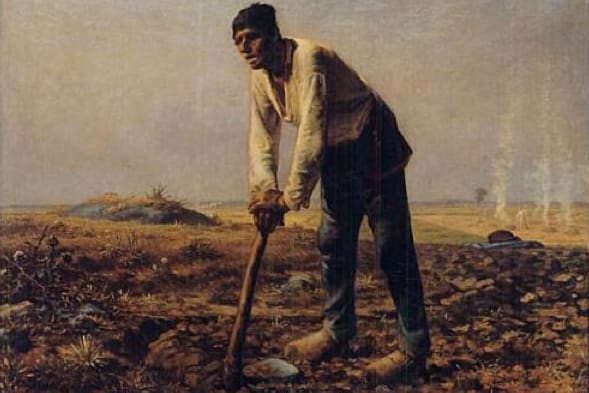

CM: You quote the surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico in the early twentieth century predicting a narrowing horizon of activities as unproductive as observation. He writes, “The writer, the thinker, the dreamer, the poet, the metaphysician, the observer—he who tries to solve a riddle or pass judgment will become an anachronistic figure destined to disappear from the face of the Earth.”

What does society lose within itself when it loses the writer, the thinker, the dreamer, the poet, the metaphysician, the observer who tries to solve a riddle? Does that mean the end of dissent?

JO: It probably would mean the end of dissent. I’m an artist; that’s my background and it’s what I teach. But it’s art that reminds us to look at things differently. That encompasses something like dissent, but it also encompasses awareness—just being aware of being alive and how strange the world is. These things are so profound, and yet they slip away very easily because we take them for granted.

There’s a whole arena of ways of thinking that are not so easily appropriated, and difficult to argue in concrete terms for their value. It’s something I have experience with as someone who teaches art to non-art majors at Stanford. Stanford is very much a part of Silicon Valley. I am constantly in the position of having to make an argument for why someone should spend time on something as seemingly useless as art, especially when it’s not formulaic, it’s not possible to optimize, and it’s not “productive” in ways that are very easy to point to.

CM: What kind of art does neoliberalism reward?

JO: Any art that looks like a product. Something I’ve been observing, and been subject to myself as an artist, is that everything is turning into a product. You are turning into a product. The idea of the self is turning into a product. Ideas, utterances are products. Then there is art that is a product.

When I talk about being an “artist-in-residence” at the dump, and I did that project with all the two hundred objects—it was a huge amount of work. But I didn’t make anything. I created context, and I created an installation. But there was a woman at the opening who was like, “I’m really confused. Did you actually make anything or did you just put things on shelves?” I now really enjoy describing my art practice as “putting things on shelves.” That was very helpful to me. But that’s a common attitude: like, where’s the art? Where’s the thing that I can buy? Where’s the thing that I can put on my wall? Where’s the big public sculpture?

This is not just recent. Throughout all of art history, artists have had to push against that conception of Art. It’s interesting to see the Instagram version of it happening now.

CM: Is “doing nothing” about putting a spanner in the works of our culture and society? Is it essentially throwing clogs in the machine of capitalism? Is this a throwback to the Luddites?

JO: Maybe? I don’t know. I’m trying to find the space to pry open the cycle between the attention economy and the mentality that it produces, and this endless positive feedback loop that happens. One place to pry that open is in the space of your own mind, and learning to direct attention in different ways, to different scales of time and space. That’s where art is really helpful.

My book is not an anti-technology book. I give examples of things like this app called iNaturalist that lets you take pictures of plants and identify them; I would count binoculars as a technology that I use very often when I go birdwatching. At the end of the book I try to imagine a utopian social network, which ends up being a non-commercial, decentralized network that still lets us share information in the ways that have always been useful and fun for us even before the internet, but have no financial incentive to keep us on them all the time and are also not selling our data or selling things to us.

I just saw, ironically, a tweet the other day that reminded me the Luddites were also not anti-technology. They were against the ways technology was being used to dispossess and disempower people. So I guess I do have that in common with them.

CM: You write, “The point of doing nothing isn’t to return to work refreshed and ready to be more productive, but rather to question what we currently perceive as productive.” But is it up to us to determine what’s productive? Isn’t what is productive determined by people other than ourselves within neoliberal globalized capitalism? Under capitalism, do we have a choice in determining what is productive, or is it completely out of our hands?

JO: It’s both. There’s a broader framework of what’s considered productive that we are all subject to, and there are smaller moments when you can walk away from that value system (probably not permanently). I talk about the communes of the 1960s and what happened with them in chapter two, as a way of blocking the exits after you read chapter one and want to retreat to the woods and never engage with capitalism again. I look at some people who tried to do that, and I end up with this weird compromise about how to disengage and engage at the same time.

I enjoy being able to pursue my curiosity—that’s how I’m reminded that I’m alive and not dead: being surprised by things and being surprised by other people. For me, the loss of this is one of the saddest things related to the loneliness epidemic.

I will say that I’ve been very surprised by how many people in tech and Silicon Valley seem to have read this book so far, and I should probably talk to some of them about what they think. I optimistically feel like if this book spread around enough, maybe someone in some position would maybe start to question what they think is productive. I don’t know, maybe that’s pie-in-the-sky. And it’s really not meant for that.

CM: You write, “Deepening one’s attention of place will likely lead to an awareness of one’s participation in history and in a more-than-human community.” What do you mean by “attention to place?”

JO: I mean it pretty literally. It comes out of my own experience of having lived in the Bay Area my entire life—over the last few years I’ve been floored by how little I knew about it. I don’t think you have to have lived in a place for a long time in order to have this experience, it’s just especially surreal for me because I’ve had so much time, and I haven’t really learned about my bioregion. I talk about bioregionalism as the idea of being familiar with the local ecology of where you live, as well as the natural history and local human history.

I’ve been really humbled by that process of learning about this area. I’m also a person who, in my art and otherwise, is generally curious. I enjoy the feeling of curiosity, so it’s been really rewarding to learn about all these different actors in this place where I live. It’s not inert. Either in ecology or in history, you’re talking about other things that are alive around you, or other people who were alive who lived in this place. On a simple level, that’s what I mean by attention to place: being aware—looking at it at all, and then starting to wonder what these things are, and wondering about different patterns. What makes this place different from another place?

That, to me, is resisting the placelessness of what we experience online, where everything is the same, and lacking in spatial and temporal context. I contrast birdwatching with looking at Twitter. When you look at a bird, if you’re a serious birdwatcher you need to know where you are, you need to know what time of year it is; all of these things will hugely narrow down what it is you’re looking at and help you understand what it is and why it’s acting the way it is. Then you go to Twitter, and you have a piece of information that has no spatial or temporal context. You’re not even seeing things in chronological order, necessarily.

Attention to place can help us learn ways of seeing and inhabiting contexts that we’ve lost from these online contexts.

CM: You write, “The villain here is not necessarily the internet, or even the idea of social media. It is the invasive logic of commercial social media and its financial incentive to keep us in a profitable state of anxiety, envy, and distraction.”

We have talked to many guests on our show about an epidemic of loneliness. What happens when we live in a society that is not only suffering an epidemic of loneliness, but also a plague of anxiety as well as all these other issues that you bring up? What happens to our society when we’re living in this era of anxiety and fear?

JO: It’s certainly not good for the individual, and it’s not good for the community. I suspect it’s also not good for things like organizing, these things that require us to reach out horizontally to the people around us. To tie it to the issue of place, there’s an idea that I encountered in a different book called “species-loneliness,” which is a term that describes the loneliness of the human species as experienced towards other life forms. Loneliness obviously occurs within our human realm, but it’s also part and parcel of a larger issue of being alienated from place—not feeling “at home,” not feeling that you are connected to things that are outside of yourself.

I’m pretty sure that somewhere in the book I use the word “entombed.” Algorithmic recommendations entomb you in this idea of yourself that becomes evermore hardened and isolated from all of the things that could surprise and change you. My boyfriend and I talk all the time about the wave of people who moved to the suburbs at some point and live these super isolated lives. Of course that’s not everyone in the suburbs, but there was a package deal that was offered and was very popular: I have my big McMansion, and I have my car, and I drive my car to my work and I don’t do things outside of that, and I don’t talk to people who are outside of my family or group of friends who I have some reason to be invested in.

Speaking of algorithms: that just feels like a living algorithm. There’s no openness to things that are truly Other from you, that would force you to rearrange how you think about things. There’s not a lot of opportunity for curiosity, either. I enjoy being able to pursue my curiosity—that’s how I’m reminded that I’m alive and not dead: being surprised by things and being surprised by other people. For me, that’s one of the saddest things that comes out of this loneliness epidemic.

CM: How much is our virtual-world attention economy distracting us from the destruction of our real world? Whether it’s climate change, or—for instance, the US is in eight wars right now, and I seriously doubt anybody can name them, although we should all memorize them. Is social media a distraction even from our nation being at war?

JO: It probably is. To go back to the very first sentence of the book, “Nothing is harder to do than nothing,” part of the reason for that is it’s hard to sit with even a vague idea of what’s happening right now. Just climate change by itself, without anything else, is already something that exists on a scale that threatens to break your brain if you try to think about it. It’s very natural for the mind to want to go anywhere other than that—anywhere other than something that’s really uncomfortable, whether that’s something that’s happening in the country or internationally, or whether it’s something that’s happening to you. If there’s something bad happening in your life, that’s not a place where your mind wants to sit. And then there is this super addictively-designed thing in your pocket that is an immediate portal not only to something else but many, many other things.

Care and maintenance are undervalued because they’ve been done for free for a long time by women; they’re invisible (being hidden in the domestic sphere), but they are the very things that keep life alive. They are the very grounds for life. There are all kinds of things like that, especially under that category of care, that make everything else possible but don’t show up in the value system.

I talk about context-collapse. On social media, there are things that are horrifying next to things that are hilarious—things that have nothing to do with each other are all stacked up next to each other, and as much as we complain about that and how distracting it is, it is very effective for a mind that’s trying to get away from bigger problems, or even just get away from that feeling of loneliness, to feel like you’re engaging with something.

I wouldn’t be surprised if that were contributing a lot to our avoiding something that’s bigger, harder to talk about, more nuanced. Figuring out how to fit yourself into that and what you should be doing or saying takes a little bit more time, and more conversation.

CM: You tell this story of the “useless tree” from a collection of writings attributed to Chuang Tzu, a fourth century Chinese philosopher:

A carpenter sees a tree of impressive size and age; the carpenter passes it by, declaring it a worthless tree that has only gotten to be this old because its gnarled branches would not be good for timber. Soon after, the tree appears to him in a dream and asks, ‘Are you comparing me with those useful trees?’ The tree points out to him that fruit trees and timber trees are regularly ravaged, meanwhile uselessness has been this tree’s strategy. ‘This is of great use to me,’ the tree says. ‘If I had been of some use, would I ever have grown this large?’ The tree balks at the distinction between usefulness and worth made by a man who only sees trees as potential timber. The tree says, ‘What’s the point of this—things condemning things? You, a worthless man about to die, how do you know I am a worthless tree?’

What happens when we confuse or conflate worth with usefulness, price with value?

JO: I’ll add something from the beginning of that story: the tree is so big that it’s shading many, many teams of oxen and animals. The other punchline is that the tree is actually very useful in that it’s caring for all these other hundreds of beings. That makes the dream sequence even funnier.

That story illustrates how a narrow concept of usefulness usually overlooks all these other things that we instinctively know are useful. I talk about care and maintenance as things that are undervalued because they’ve been done for free for a long time by women; they’re invisible (being hidden in the domestic sphere), but they are the very things that keep life alive. They are the very grounds for life. There are all kinds of things like that, especially under that category of care, that make everything else possible but don’t show up in that value system.

Sleep is another funny example. I was really inspired by this book called 24/7 by Jonathan Crary; the subtitle is Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. He talks about sleep as the last remaining vestige of human animality that can’t be appropriated. He explains all of these assaults on sleep and our need for sleep, all these attempts to do away with it, like the development of drugs. It’s very similar to the carpenter in that story. If you’re a person who only sees time as money, and you only see it as potentially producing outcomes or deliverables or products, sleep appears useless.

Of course we all know sleep is not useless. I have the humility to allow that sleep is useful in ways that I don’t understand and I might not ever understand. That’s fine. I don’t need to be able to articulate that. I recognize the necessity of something like sleep. There a lot of things that are similar to that.

CM: You discuss what you call “refusal in place” as you look to the history of refusal, and you try to show how that “creative space of refusal is threatened in a time of widespread economic precarity, when everyone from Amazon workers to college students see their margin of refusal shrinking and the stakes for playing along growing. Thinking about what it takes to afford refusal, I suggest that learning to redirect and enlarge our attention may be the place to pry open the endless cycle between frightened, captive attention and economic insecurity.”

How can enlarging our attention address precarity?

JO: There are a couple different ways. On the individual level, there are certain economic realities that a lot of us are subject to, in different ways—at least in my experience, there are interstitial moments where I can get away with paying a different kind of attention than what is trying to be extracted from me. Some of this stuff is involuntary, but some amount of it, for some people, is voluntary, and it’s about finding those moments where you have a small margin to disengage within the space of your own mind.

If more people are able to disengage even in just some small way—not by moving out to the woods or deciding to give up and forsake the world entirely, to quit all social media and stop reading the news—and if more people were able to find more agency in the way that they direct their attention, it might remind us of the value of certain kinds of conversations and reflections, and help us have them.

I end the book with the idea of a non-commercial social network. I look at the history of organizing and how much concentration that takes, both on the level of the individual and collectively. I think of small groups within large federations, small groups in which people are able to have nuanced conversations and feel recognized and accountable and have a context for what they’re saying (versus on something like Twitter), and then the larger-order coordination of those groups in order to share information and decide on different forms of action.

I would hope that my suggestions around attention would fit in somewhere there, that it would make something like that easier, not to mention just remind us of the value of those kinds of conversations and groups.

CM: Jenny, thank you so much for being on our show this week.

JO: Thank you.